|

Location

The site of the ruined city of Kunya or Old Urgench lies about 2.5km south of the centre of the modern town of Kunya Urgench in the Dashoguz

welayat of northern Turkmenistan. The site is about 43km west southwest of No'kis. Foreign tourists can cross the Karakalpak-Turkmen border

checkpoint between Xojeli and Kunya Urgench, but must be in possession of a visa for Turkmenistan . See the

"How to Get There" page of our

Tour Guide.

The Sultan Tekesh Mausoleum and the adjacent Qutlugh Timur Minaret.

Image courtesy of the Ministry of Culture, Ashgabat.

From the Central Bazaar in Kunya Urgench drive west for 400 metres and turn left, crossing the Khan-yab canal. Just over 2km from the canal the road

reaches the northern boundary of the Archaeological Park. There is a car park on the left next to the Tura beg Khanum Mausoleum. There are official

opening hours and an admission charge. This used to be 11,000 manat for foreigners and 1,000 manat for locals, but may now have

increased.

Excavations

Despite being one of the most important medieval sites in Khorezm - its capital for over half a millennium - Kunya Urgench has been very much neglected

by the archaeological fraternity. The reasons for this are not entirely clear - it was not because the site was located in the Turkmen rather than the

Uzbek SSR. The Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographical Expedition conducted a large amount of work in northern Turkmenistan from the 1950s through to

the 1980s. Maybe Tolstov was not excited by such an obvious and easily accessible site.

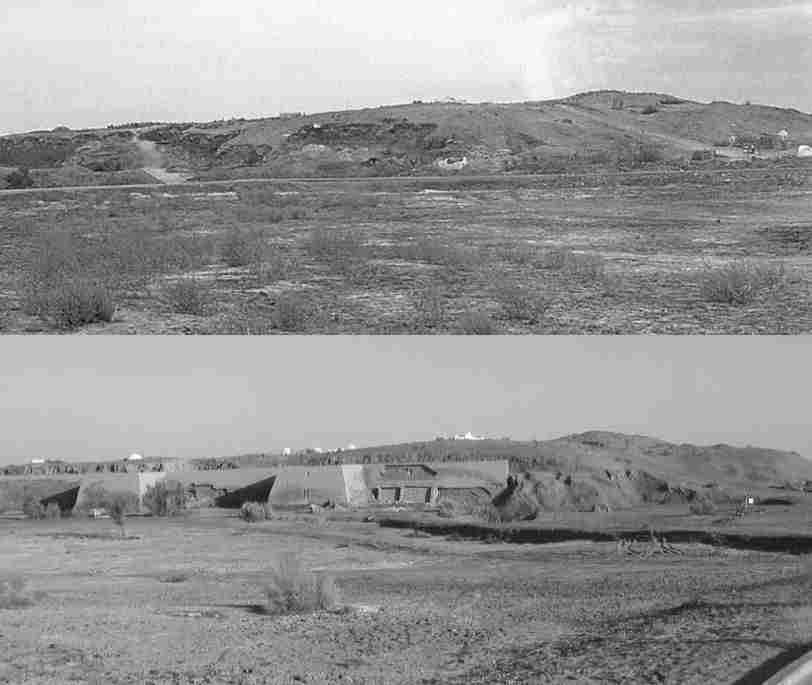

The Kunya Urgench site from the south.

Qutlugh Timur Minaret left; Sultan Tekesh Mausoleum centre; and Fakhr ad-Din Razi Mausoleum right.

The failure to conduct rigorous and persistent research on the site means that there remains considerable uncertainty surrounding the dating and function

of many of the monumental buildings that occupy the archaeological park.

The first scientific study of Kunya Urgench was undertaken in 1928 and 1929 by an expedition from the State Academy for the History of Material Culture

led by A. Yu. Yakubovsky. In 1938 the architect V. I. Pilyavsky surveyed the site and measured and described its monuments. Photographs appeared in a

1939 publication on the monuments of Turkmenia.

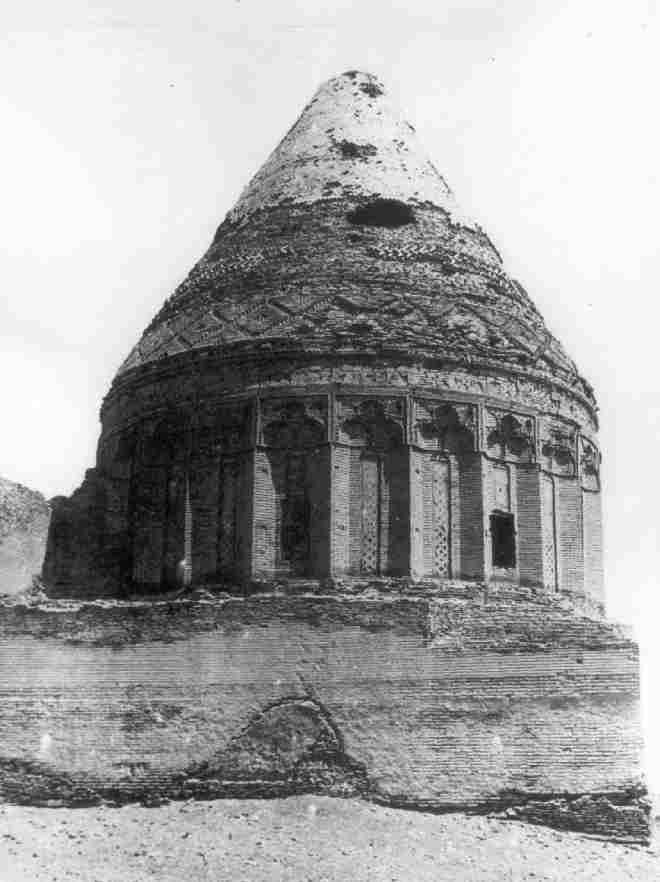

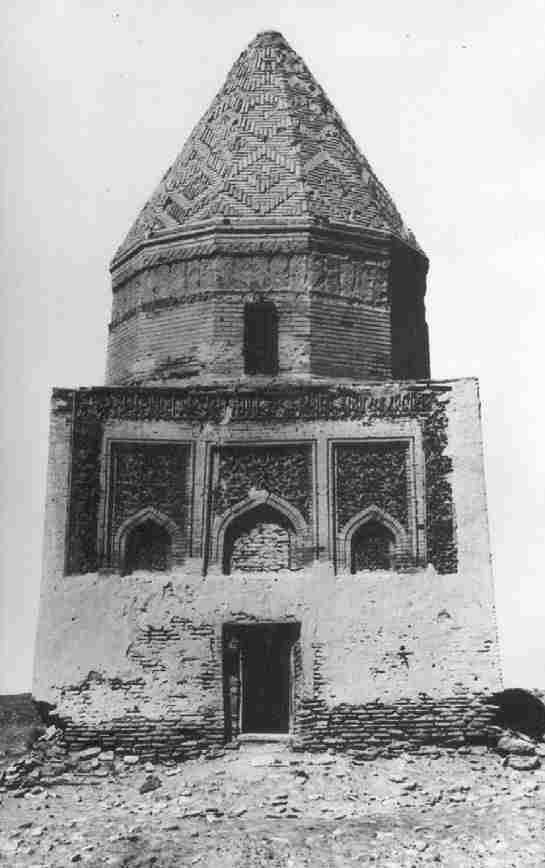

The Sultan Tekesh Mausoleum photographed by A. Yu. Yakubovsky in 1928.

After the war, Sergey Tolstov's Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographical Expedition began the first archaeological studies on the site. In 1952 they

examined three objects in the medieval citadel known as Tash Qala the southern gate and wall, part of the urban district and the remains of a minaret.

Amazingly their work was not continued in other parts of the ruined city. No further archaeological research took place until 1979.

The architectural details of the monuments and the methods used to construct them had already been studied by N. S. Grazdankina during the 1950s.

Between 1958 and 1960 Aleksandr Vinogradov, A. Asanov and I. I. Notkin drew up plans of the monuments and recorded their physical status as a basis for

making recommendations about their restoration. In the 1960s and 1970s the monuments at Kunya Urgench continued to attract the general attention of a

variety of Central Asian scholars, including Mikhail Evgeniyevich Masson and his wife Galina Anatolyevna Pugachenkova.

Archaeological work partly resumed between 1979 and 1985, with the Uzbek Institute of Conservation excavating the so-called "caravanserai portal" in the

south of the site.

More extensive work was conducted between 1988 and 1993 by the Kunya Urgench Archaeological Expedition of the Institute of History of the Academy of

Sciences of Turkmenistan, led by Kh. Yusupov. This included excavating the western part of the earliest settlement on the site, Kyrk Molla, in 1991.

This exposed the foundation of a defensive wall with towers.

A Short History of Gurganj/Urgench

To properly understand the archaeological site it is helpful to have an overview of its traumatic history. In short the city developed from the north

to the south over a period of more than two thousand years.

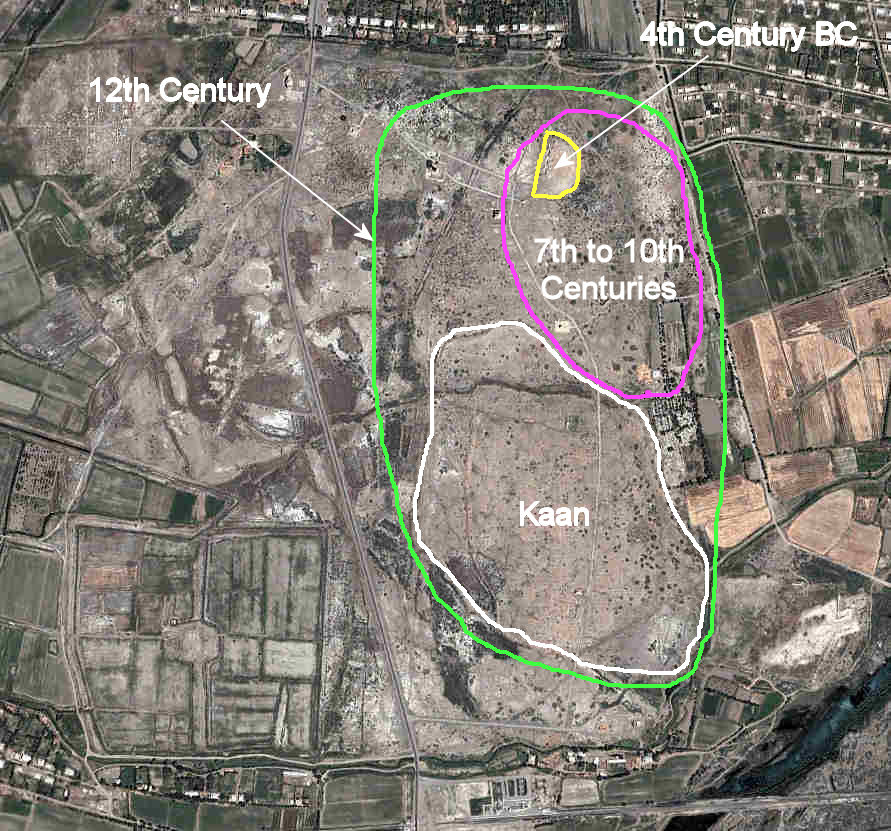

The earliest settlement, known as Kyrk Molla, is located in the north-eastern corner of the complex. On the basis of finds of ceramics, it seems to date

from the 4th century BC, a time when Khorezm had just gained its independence from the Persian Achaemenid Empire. It was one of many settlements on the

western bank of the Amu Darya at that time, along with Hazarasp and the Ichan qala at Khiva. Some have suggested that it might have been called Urva,

one of the regions listed in the Zoroastrian Avesta. However many scholars associate Urva with Kabul in Afghanistan. It seems to have been occupied well

into the 6th and 7th centuries AD, the Afrigid feudal period.

It was not until the 7th century AD that a new fortified town sprung up just south of the ruins of Kyrk Molla. According to the early Arab historians,

in 712, the date of the Arab invasion, the town was in a breakaway region ruled by an independent "King of Khamjird" who may have been the brother of

the Khorezmshah. It is not clear whether Khamjird was the name of the new town as some have suggested - or of some neighbouring city or indeed of the

region as a whole. While the Arab general Qutayba was preparing to invade Samarkand, the Khorezmshah made a secret pact with him as a result of which

Khorezm became a tributary state in return for Qutayba's military intervention in deposing the rebellious King of Khamjird.

The geographic development of the pre-Mongol city.

The Arabs named the new town Jurjaniya, although the local people came to call it Gurganj. It became an administrative capital for the Arab deputies,

who were responsible for taxation and the promotion of the Muslim faith. As the most northerly town in Khorezm it soon became a major trading centre

for the surrounding nomadic tribes and a thriving economic and cultural centre, greatly helped by the revitalising of the local agricultural region

thanks to a change in the flow of the Amu Darya. Gurganj was surrounded by a defensive wall and probably had a central square surrounded by houses and

winding streets, along with the rulers palace (the Kyrk Molla?).

The anonymous Hudûd al-Âlam, written around 982, noted that although Gurganj had previously belonged to the Khorezmshah, it was now governed

independently. It briefly added that:

"The town abounds in wealth, and is the Gate of Turkistan and resort of merchants. The town consists of two towns: the inner one and the outer one.

Its people are known for their fighting qualities and archery."

The chronicler al-Muqaddasi also described the town in the 10th century when it was the seat of the Amir Ma'mun. It had four gates and the waters of

the canals came only as far as those gates since there was insufficient room for the canals to continue into the city. The palace of Ma'mun was located

close to the Hajjaj gate. Apparently the gates of the palace itself were of particularly beautiful workmanship, having no equal in the whole of Khurasan.

Somewhat later, Ma'muns son Ali, who succeeded him in 997, built another palace in front of his father's. He also laid out a square in front of the

palace gates in imitation of the Registan in Bukhara, and this was later used as a livestock market. In 1010, another of Ma'muns sons, Ma'mun ibn

Ma'mun, built a minaret. One of the major city sights was to be seen about ¼km from the centre of Gurganj, where the course of the Amu Darya was

deflected to the east by a huge wooden dam. Prior to the construction of this dam the water came up to the walls of the town.

In 995 the army of the Amir Ma'mun deposed the Khorezmshah and the capital of Khorezm transferred from Kath to Gurganj. However his dynasty was short-

lived. In 1017 his son Ma'mun II was overthrown by the Ghaznavids (from Afghanistan) who placed their own representative on the Khorezmian throne. Twenty-

six years later the Ghaznavids were in turn ousted by the Seljuk Turks of Iran and Khorezm became a province of Khurasan. Seljuk authority over Khorezm

rested with Anush-tegin, a former slave who had risen through the ranks to become a senior military general. In 1097 Anush-tegin's son, Qutb ad-Din

Muhammad, was appointed Khorezmshah, the first of one of the most successful line of rulers in Khorezm's history the Anushteginid dynasty of

Khorezmshahs.

It was an unstable time when the Aral region was facing an influx of warlike Turkic nomads known as Qipchaqs. The Khorezmian rulers progressively

formed alliances with the Qipchaqs and recruited them as a mercenary army. Indeed the economy of Gurganj was partly dependant on trade with the nomads.

By the 12th century Gurganj was by far the largest city in Khorezm. Aerial photography suggests that the city had expanded to the west of the old

Arabic citadel, on both the north and the south sides of a small river channel, a branch of the Darya Lyk. In the south-west of the city the "new town"

district of Kaan, only developed during the previous century, had many parallel streets oriented in an east-west direction. However because the city's

defensive walls had been built along the banks of natural rivers the city had quite an irregular shape.

It is possible to assemble a cameo of the city from the scraps of information provided by writers such as Nesevi, writing just before the succession of the

Khorezmshah Tekesh, and Juvaini writing after the Mongol conquest. The city was walled and defended by gates, one of which was called the Aqabilan Gate

and a second the "gate of peace". The city was divided up into residential blocks and contained a magnificent Shafi'ite cathedral mosque, a mosque

library, five teaching medressehs, and the "old" Kushk-i Akhchak palace. Juzjani mentions the bridge across the river and "the garden of amusements"

just outside of the city. Later information of unknown origin suggests it also contained a bazaar, baths, a minaret, the tomb of the Khorezmshah

Muhammad's daughter and several more mausoleums. The Syrian geographer Yaqut, who lived in the city from 1219 to early 1220, considered Urgench to be the most

extensive and the richest of all the towns he had seen.

It all came to an end in 1221. The Khorezmshah Ala ad-Din Muhammad began exchanging embassies with a Mongol ruler in the east named Chinggis Khan.

In 1218 a Mongol caravan was attacked by the authorities of Otrar, an oasis on the north-eastern frontier of Khorezm. Perhaps the caravan had been a

cover for Mongol spies. Whatever the reason, its merchants were massacred and its merchandise seized. Chinggis Khan demanded that the Khorezmshah

extradite his governor for punishment in Mongolia. Muhammad's refusal precipitated one of the greatest events in world history - the Mongol invasion

of western Eurasia. At the start of 1221 a large Mongol army surrounded the walls of Gurganj, supported by Chinese military engineers. Within months

the walls had been breached and the defenders massacred or enslaved.

While the city may have been badly damaged, the Mongols had no desire to destroy it. They renamed it Urgandj or Urgench and it became part of the

Khanate of Qipchaq (later to be known as the Golden Horde) along with the rest of left bank Khorezm, ruled from the nomadic capital of the Mongols on

the Volga. Urgench rapidly recovered to become a thriving commercial centre, a staging post on the important trading route between Europe and the

Black Sea ports in the west and Mongolia and China in the east. Many Italian merchants established trading operations in the city, which was also the

location of one of the Golden Horde's three mints. Urgench also became an important religious Sufi centre and a seat of Islamic learning, culture and

literature. The city rapidly expanded in all directions, its ramparts stretching 3km from north to south and by 2km from east to west.

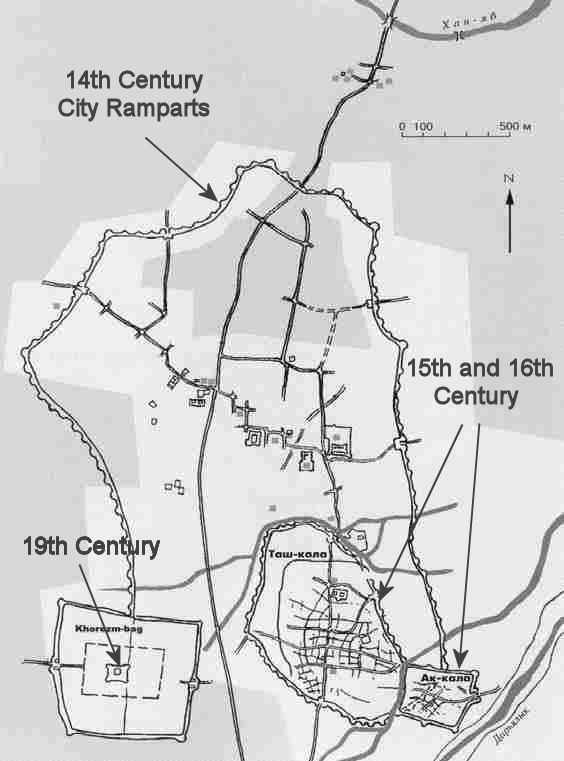

The ramparts of the Golden Horde city, now destroyed by ploughing, and post-Mongol developments.

Ibn Battuta provided us with an excellent eyewitness account of the bustling city when he passed through it on his journey to Bukhara in the 1330s.

He had just spent 30 days crossing the Ustyurt desert after leaving Sultan Uzbek's brand new capital of Saray al-Jadid. He was clearly impressed:

" ... we arrived at Khorezm [Urgench] which is the largest, greatest, most beautiful and most important city of the Turks. It has fine bazaars and

broad streets, a great number of buildings and abundance of commodities; it shakes under the weight of its population, by reason of their multitude,

and is agitated by them in a manner resembling the waves of the sea. I rode out one day on horseback and went into the bazaar, but when I got halfway

through it and reached the densest pressure of the crowd at a point called al-Shawr [the crossroad], I could not advance any further because of the

multitude of the press, and when I tried to go back I was unable to do that either, because of the crowd of people. So I remained as I was, in

perplexity, and only with great exertions did I manage to return."

The city had a new college (medresseh), recently built by its governor Qutlugh Timur in which Ibn Battuta stayed, a cathedral mosque built by the Amir's

pious wife the Khatun (queen) Tura beg, a hospital with a Syrian doctor, and a nearby hospice built over the tomb of Najm al-Din Kubra.

The city's residents impressed Ibn Battuta:

"Never have I seen in all the lands of the world men more excellent in conduct than the Khorezmians, more generous in soul, or more friendly to strangers."

The local people were also extremely pious, possibly because the muezzins of each mosque would visit the neighbouring homes and remind them that the hour

of prayer was approaching. The imam would fine those who failed to attend and beat them with a whip, which was prominently displayed in the mosque as

a reminder! The city was close to the Jaiyhun River [then the main channel of the Amu Darya, now the Darya Lyk], which was navigable by boat

in the summer, the journey from Termez taking 10 days. In winter the river froze solid for five months every year, and people walked across it, some

perishing in its waters when the ice began to melt.

This must have been the heyday of the city. In 1346 the Black Death erupted at Saray on the Volga, the heart of the Khanate of Qipchaq. It cannot have

taken long for the epidemic to have passed along the main trading route to Urgench, although we have no historical record of its timing or impact.

Worse was to come. In 1388 the whole city was destroyed by Timur, as were most other parts of Khorezm. Timur's campaign was not only aimed at

eliminating the military threat posed by Khorezm and the remnants of the Khanate of Qipchaq, but at destroying an important commercial and cultural

competitor. As such most of the city was deliberately demolished. The historian Ibn Arabshah reported that after ten days of destruction, only the

mosque and its minarets were left standing. Timur is reported to have ordered that the ground on which the city stood should be ploughed and sewn with

barley.

Although Timur authorised the rebuilding of just one quarter of Urgench in 1391, it was the end of an era. The destruction of the dams controlling

the flow of the Amu Darya meant the river was now free to revert to its natural direction of flow towards the Sarykamysh Lake. The level of the Aral

Sea began to fall and the Amu Darya delta began to dry out forcing its nomadic population to migrate. It was the beginning of an environmental crisis

that would last for 200 years.

In 1430 the newly built city of Urgench Tash Qala - was sacked by Abu'l Khayr Khan, the ruler of a new nomadic confederation known as the Uzbeks. He

installed an Uzbek prince as the new ruler, the first of a new dynasty of Uzbek Khorezmshahs. As an increasing number of Uzbek nomads migrated into the

region, their rulers engaged in almost permanent civil war, fighting each other for control. In about 1520 a dispute between the royal princes resulted

in Urgench being placed under siege for four months. Despite the unstable conditions, Urgench continued as the capital of Uzbek Khorezm until 1539 when

Qal Khan temporarily relocated it to Devkesken qala and the city of Vazir.

The post-Timurid town was only a fraction of the size of the former city, occupying about three-quarters of the single pre-Mongol district of Kaan.

Tash Qala was walled and its main street ran from a northern gate to a southern gate, which faced the Darya Lyk. Numerous side streets branched off

to the east and west of the main street, breaking the town up into small residential blocks. In the southern part of the town was a walled caravanserai

built behind the finely decorated pre-Mongol portal. However much of the former agricultural region surrounding the city remained fallow. At some

time during the 16th century the rectangular mud-brick fortress of Aq qala was built between the stream that bordered the south-east corner of the town

and the Darya Lyk. The shape of its wall openings suggests it was designed for the modern age of guns and bullets rather than the days of bows and

arrows.

Hajji Muhammad, who was known as Hajjim Khan, moved the capital back to Urgench in 1558. The town was described later that year by an English merchant

named Anthony Jenkinson, who arrived there on the 16th October:

"This city of Urgench standeth in a plane ground, with walls of earth, by estimation four miles about it. The buildings within it are also of earth but

ruined and out of good order: it hath one long street that is covered above, which is the place of their market. It hath been won and lost 4 times

within 7 years by civil war, by means thereof there are but few merchants in it, and they are very poor, and in all that town I could not sell above

4 kersies [woollen broadcloths]. The cheifest commodities there sold are such wares as come from Bukhara and out of Persia, but in most small quantity

not worth the writing."

As Jenkinson had observed on his way through Vazir, the Amu Darya was changing its course, reverting towards the Aral Sea. The region around Vazir

and Urgench was drying out and its agriculture was failing. In 1602 Hajjim was succeeded by his son, Arab Muhammad, who began ruling Khorezm from Khiva.

Urgench struggled on until 1646 when Abu'l Ghazi Khan finally relocated its residual Uzbek population to the region of Khiva - founding Yani or New

Urgench, the present day city of Urgench.

The Russian merchant Rukavkin visited the site in 1753 and referred to it as "the empty city of Urganich". He mentioned that it had a wall, two mosques,

a house belonging to the Khan and several other houses with dilapidated roofs.

The present small town of Kunya Urgench developed in the 19th century following Allah Quli Khan's decision to settle Turkmen nomads in the region and

to construct the Khan-yab canal in 1831. Two decades later Muhammad Amin Khan (ruled 1846-55) built a fortified residence, today known as Khorezm Bag,

in the south-west corner of the old city. The presence of the nearby mausoleums encouraged the local people to believe that the archaeological ruins

were a holy site. Over the years they turned it into a huge cemetery. Yet even by 1900 the town still only had 50 houses. When the American irrigation

engineer Lyman Wilbur visited the town of Kunya Urgench in 1930 or 1931 he described it as "a pitiful remnant of the great city that it once was."

The town with its grid layout only began to expand following the establishment of collective farms in the region during the Stalin era. Its main

industries are tomato processing, carpet making, cotton storage and vodka distilling.

The main reason that people come to visit the town today is to see the neighbouring ruins.

The Site of Urgench

In the mid 1990s the site of Old Urgench was still a fascinating ramshackle wilderness of partially restored monuments surrounded by a huge cluttered

Islamic cemetery. Thanks to the Turkmenistan government's desire to promote tourism and financial grants from UNESCO and various other donors, the

site has been progressively transformed into a bland landscaped "archaeological park", with tarmacadam walkways, featureless open spaces and signboards.

Even worse, the monuments are steadily being rebuilt using modern materials, transforming them into cold characterless shells. These magnificent ruins

have stood on this site for over six hundred years, reminders of Timur's devastating campaign of destruction. Robbed of building materials by later

occupants of the city; damaged by weather, earthquakes and visitors; these buildings desperately needed to be stabilised and preserved. Surely there

must have been a better choice than the irreversible and ironically destructive option of reconstruction?

Looking towards the Seyit Akhmet and Tura beg Khanum Mausoleums from the old Kunya Urgench cemetery in 2003.

In 2005 Kunya Urgench Archaeological Park became a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It only receives about 2,000 foreign visitors a year, a trivial number

compared to the 150,000 annual Turkmen visitors. Many of the latter come for religious reasons.

Kunya Urgench Archaeological Park. Section 1: Old Urgench; Section 2: Najm ad-Din Kubra Mausoleum;

and Section 3: Ibn Khajib Mausoleum.

Some of the major monuments of Kunya Urgench. They can all be reached on foot from the car park.

We describe the main monuments within the park in the sequence that they are encountered on leaving the car park.

Tura beg Khanum Mausoleum

The so-called Tura beg Khanum Mausoleum is an architectural masterpiece that in a restored state would easily rival the later mausoleums of Samarkand.

It was built just to the north-west of the centre of the Golden Horde city during the 14th century, most probably around 1370 although one source has

suggested the 1320s, which seems unlikely.

The elegantly proportioned Tura beg Khanum Mausoleum.

There are numerous theories concerning its origins and purpose, none of which can be supported by hard evidence.

It is generally linked to Tura beg Khanum, the wife of the Golden Horde ruler of Khorezm Qutlugh Timur (ruled 1321-1333), who was appointed

by Sultan Uzbek. Amir Qutlugh Timur was the son of Uzbek's maternal aunt. If it had been sponsored by Tura beg Khanum it is surprising that the

building was omitted from the architectural highlights described by ibn Battuta.

In the early 1990s Kh. Yusupov suggested that it was a pre-Mongol palace dating from the 12th or early 13th century. However Central Asian palaces

of this period normally had a central courtyard surrounded by four ayvans. Furthermore the mosaic and majolica tiles used on the building

were manufactured using 14th century Khorezmian ceramics technology and are similar to those encountered on the Najm al-Din Kubra Mausoleum, built in

1340.

The rectangular portal with its arched entrance and muqarnas.

A more recent and rather obtuse theory has proposed that the building might have been sponsored by one of the sisters or wives of Timur as part of the

ruler's quest for Chinggisid legitimacy through his female lineage. It is hard to see why and for what practical purpose such a monumental building

would have been constructed outside of Timur's Chagatay domain.

The most likely hypothesis is that the building was a mausoleum for the somewhat later and short-lived dynasty of Qon'ırat Sufi Khorezmshahs,

which began with the enthronement of Aq Sufi Khan in 1359. One suggestion is that it contained the tomb of the Khorezmshah Husayn Muhammad Giyath

ad-Din Sufi (1361-1372), who enraged Timur (Tamburlaine) by annexing the Chagatay territory of Kath and right bank Khorezm. He died during the

resulting siege of Urgench.

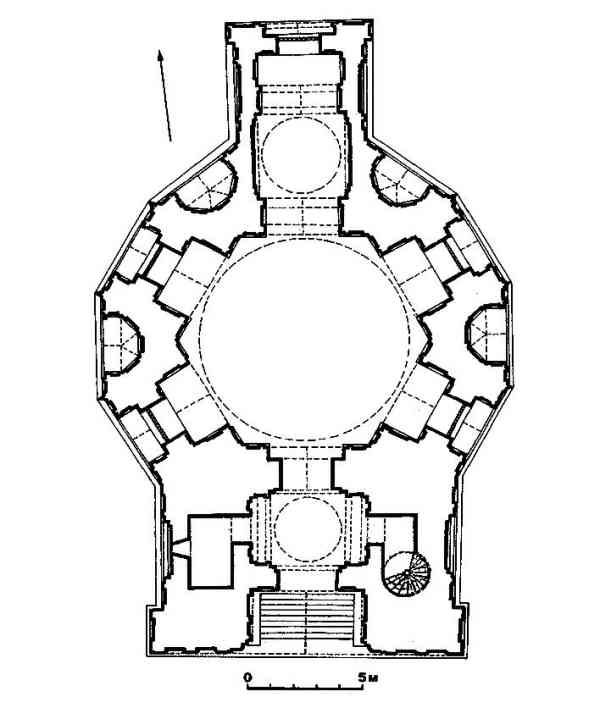

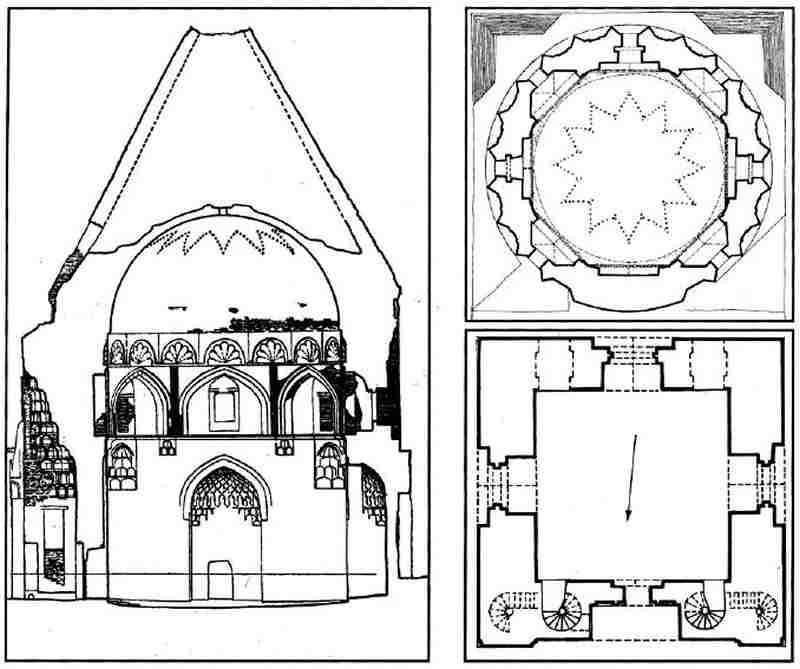

Plan of the lower structure, drawn by M. M. Tuhtaev in 1985.

The ruins of this building demonstrate the advanced state of Khorezmian architecture and craftsmanship under Golden Horde rule. Indeed following the

1388 conquest, the master craftsmen of Khorezm were enslaved by Timur and relocated to Samarkand to work on his own monumental palaces, mosques and

medressehs.

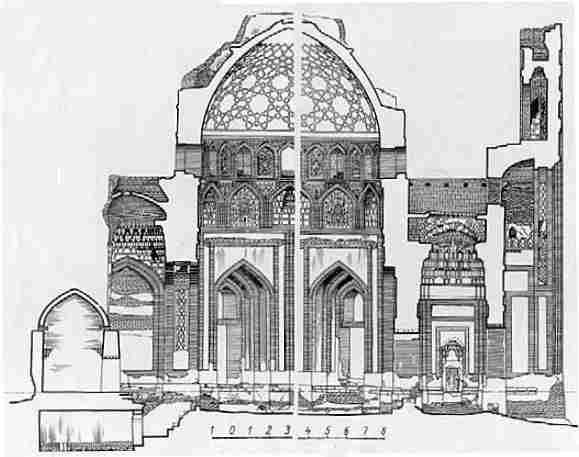

Central cross-section of the mausoleum, drawn by A. N. Vinogradov in 1960.

The mausoleum was primarily constructed from a mixture of yellow-coloured, fired clay brick and tile, and was extensively decorated with glazed tile

work. The heart of the building is a massive cylindrical-shaped drum supporting a complex domed roof structure. The outer shape of the drum is based

on a twelve-sided dodecagon, although the internal chamber is hexagonal. Only eight sides of the dodecagon appear on the outside, each incorporating

a tall arched niche with a muqarnas vaulted roof. Four of these niches contain windows.

Side view showing three sides of the dodecagonal drum and the rebuilt northern portal. Note the rising damp.

The drum supports an upper cylindrical tower containing twelve evenly spaced arched windows, each separated internally by an arched niche contained

glazed tile work decoration. Most of the multicoloured hexagonal tiles that once decorated the outside of this cylindrical tower have become detached,

although a few smaller tiles remain in the narrow borders.

The tileless cylindrical tower, the restored middle dome and a fragment of the outer conical dome.

The roof consisted of three superimposed domes, the purpose of the 9-metre diameter innermost dome being solely to support the magnificent decorative

ceramic tile work, most of which is still intact. This is laid out in the form of a complex angular lattice with the spaces in between containing

circular and star-shaped arrangements of motifs, which one author has compared to a firework display.

The magnificent internal decoration of the tower and dome.

The intermediate dome stabilised the whole building and was meant to be concealed, although its restored structure now forms the present outer roof.

The external dome was meant to be conical and decorated with dark turquoise glazed tiles. It would have looked magnificent but sadly does not currently

exist. Only a small part of the lower section can still be seen, along with a lower band of multicoloured arabesque floral tiles glazed in dark blue,

light blue, white, yellow and terracotta. The conical roof was either subsequently demolished or not fully completed at the time of the Timurid

conquest.

Decorative tile work below the hip of the conical roof.

A huge and imposing rectangular entrance portal or pishtaq, some 25 metres high, is positioned on the southern side. Its arched entrance

contains the remains of the original muqarnas, or corbelled vaulted ceiling and leads into a vestibule, with ancillary chambers on each side.

The vestibule on the right hand side contains a circular staircase leading to the roof of the portal. The entrance vestibule leads directly into the

main hexagonal chamber of the mausoleum. Much of the tile work on the portal seems to have been lost and this, together with no trace of a dedicatory

inscription, has led some to argue that the exterior decoration was never completed.

The walls of the mausoleum were restored between 1983 and 1993 and the collapsed northern portal was reconstructed. Between 1999 and 2000 the main

inner dome and two ancillary domes were restored. However much of the remaining tile work still remains in a precarious state and requires conservation.

Seyit Akhmet Mausoleum

Sadly the original building completely collapsed in 1993 and has been completely reconstructed on the original foundations using new materials.

Qutlugh Timur Minaret

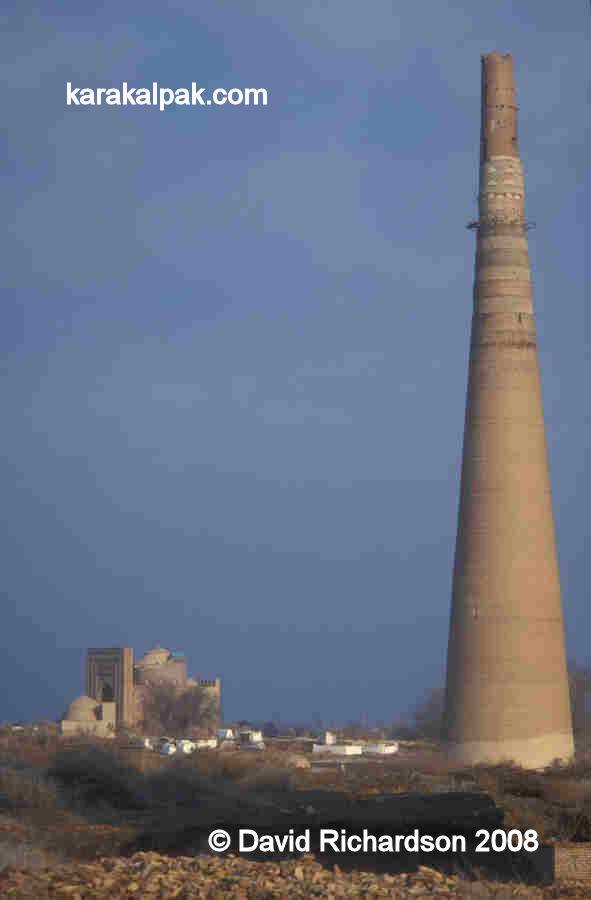

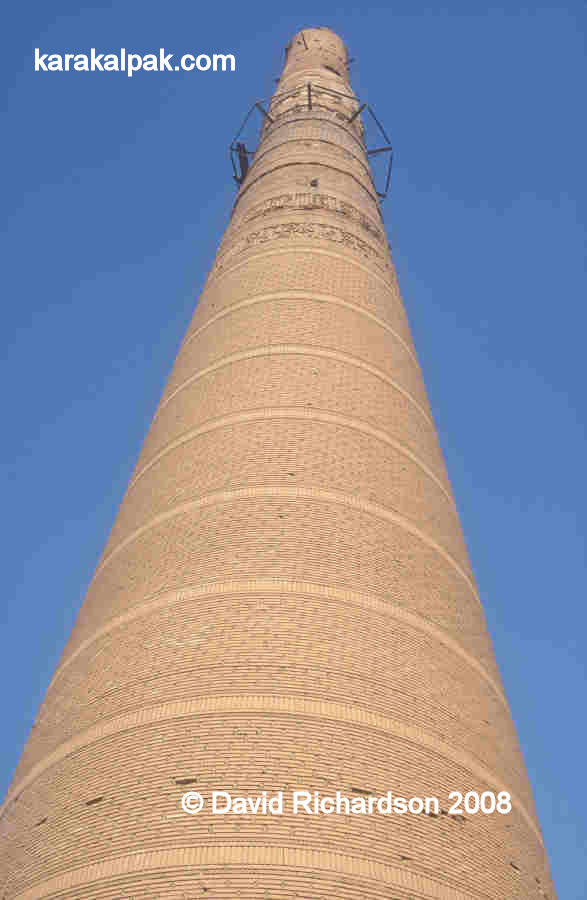

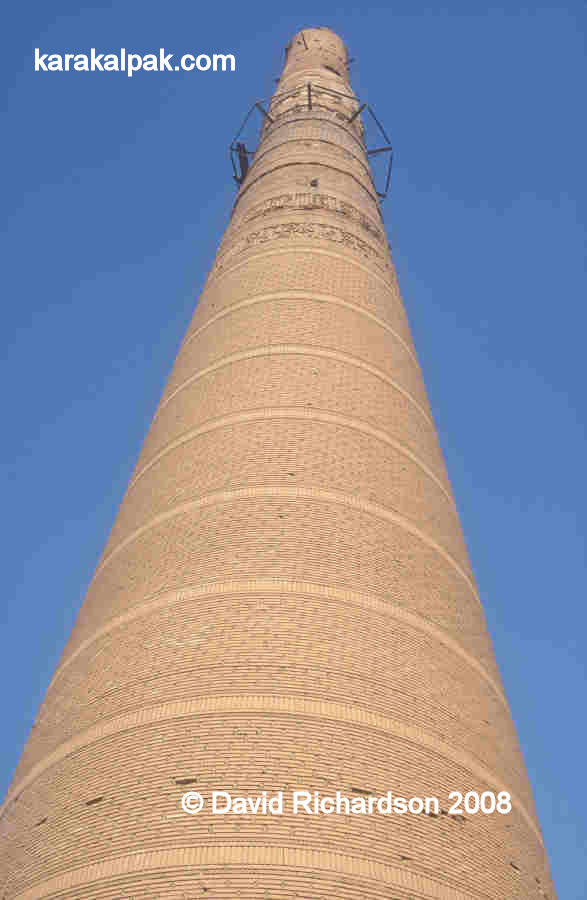

The precarious looking minaret named after the Khorezmshah Qutlugh Timur is all that remains of the city's Friday Mosque. It is supposedly the tallest

medieval minaret in Central Asia. Its height of 60 metres just beats that of the much more modern 57-metre high Islam Hoja Minaret in Khiva, only

commissioned in 1910. Presumably it would have originally been some 5 metres taller since the chamber for the muezzin is missing.

Qutlugh Timur Minaret with the Tura beg Khanum Mausoleum in the distance.

In the more recent past the minaret supported a wooden lantern, constructed upon wooden beams inserted into the brickwork. It apparently served as a

lighthouse and a watch tower.

Silhouette of the Qutlugh Timur Minaret and Sultan Tekesh Mausoleum.

Medieval minarets in Central Asia can be classified into two basic forms those that are smoothly tapered and those that are stepped. This clearly

falls within the former category, having smooth sides and a diameter of 12 metres at the base and only 3 metres at the very top. The top of the minaret

is accessible by means of a windowless internal helical staircase with 145 steps, the entrance to which is 7 metres above ground level presumably a

level that was once accessed from the adjacent mosque, probably by means of a wooden bridge. The diameter of the staircase narrows with increasing

height.

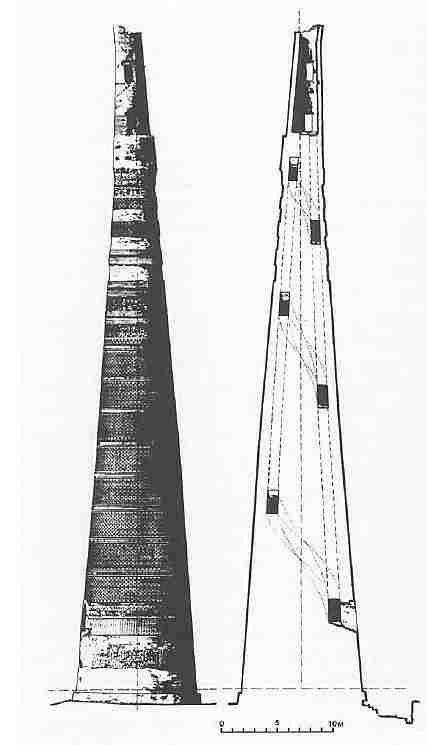

Scale drawing and cross-section of the minaret by A. N. Vinogradov, 1961.

The minaret is constructed of yellow fired-clay brick on a 3-metre deep foundation. Much of the original brickwork is badly weathered. The minaret was

decorated on the outside with some 18 bands of patterned brickwork separated by sections of plain brick. Some of these bands contained glazed inserts

similar to those found in the pre-Mongol Mazlum Sulu Khan Mausoleum at Mizdahkan. There were also originally six bands bearing inscriptions in Kufic

script, although only three remain today.

The upper unrestored sections of the minaret, showing one band of carved Kufic script and two bands decorated

with decorative blue-glazed tile inserts.

The location of the minaret is in the northern segment of Kaan, the new part of Gurganj built in the 11th and 12th century, and also in the very heart

of the 14th century Golden Horde city of Urgench.

When the minaret was examined by A. Yu. Yakubovsky in the late 1920s he described it as "a typical construction of the Karakhanid epoch" - in other

words, mid 9th to early 13th century. However he then discovered that the lowest band of inscription at the level of the entrance to the minaret

stated that it was built by Qutlugh Timur (the two higher bands contain Quranic verses). Yakubovsky therefore described the minaret in the literature

as the "minaret of Qutlugh Timur" with a proposed date of construction in the second quarter of the 14th century. There was also a large hill located

just west of the minaret strewn with fragments of fired brick and multicoloured tiling. Yakubovsky interpreted this as the ruins of the related

cathedral mosque, which he assumed had been restored when the minaret was constructed during the era of the Golden Horde.

Damage to the original cladding on the south-east side of the minaret coupled with the raised entrance provides additional evidence that the minaret

once flanked a large building, presumably a mosque.

In the meantime many scholars have observed that the minaret has an archaic appearance and bears many resemblances to the 11th and 12th century

Qara-Khanid minarets at Uzgen, Buran, Bukhara and Vabkent.

|

The lower restored sections of the minaret.

In the late 1980s the lower part of the minaret was cleaned and restored and the internal staircase repaired. V. V. Zotov examined the architectural

and decorative design of the minaret at that time as well as the construction methods and materials, concluding that the minaret was pre-Mongolian.

Zotov also established that the inscription referring to Qutlugh Timur was not original but had been added at some time after its initial construction.

The most likely possibility is that the mosque and its associated minaret (or minarets) were constructed in the 11th or 12th century, prior to the

Mongol conquest, during which they were badly damaged. They were both later restored during the reign of Qutlugh Timur. The inscription on the minaret

(which is general and does not refer to the minaret specifically) therefore refers to the activity of restoration and not to the original construction.

In 1999 the top section of the minaret was

partially reinforced. Today the top of the minaret is out of alignment by over one metre demanding more reinforcement in the future to prevent a

collapse.

To complicate matters further there are the remains of a second minaret in the archaeological park 800 metres to the south east of this one see below

for details.

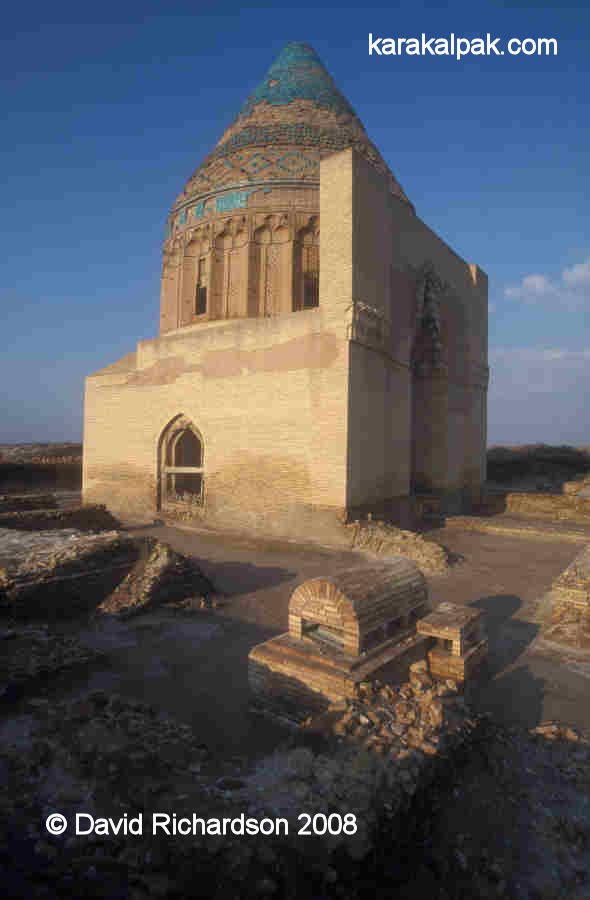

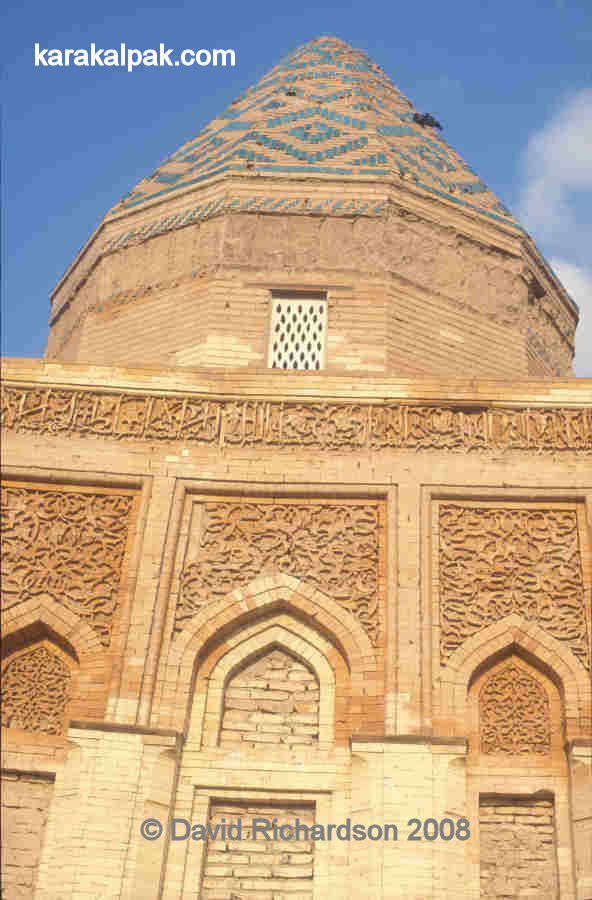

Sultan Tekesh Mausoleum

Like the Qutlugh Timur Minaret, the Sultan Tekesh Mausoleum lies at the centre of both the 11th-12th century and the 14th century cities. It is another

outstanding building.

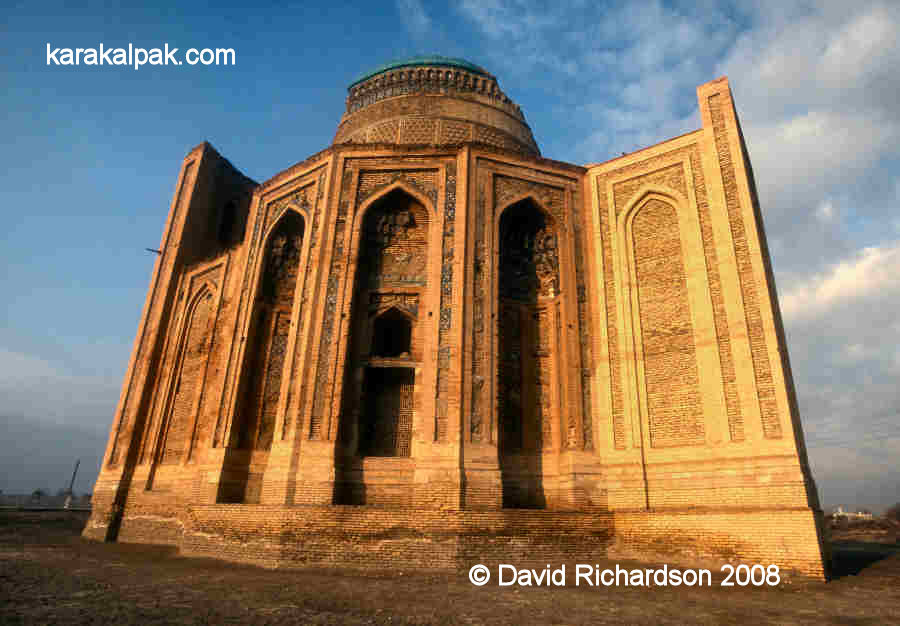

The Sultan Tekesh Mausoleum and the adjacent Qutlugh Timur Minaret.

Image courtesy of the Ministry of Culture, Ashgabat.

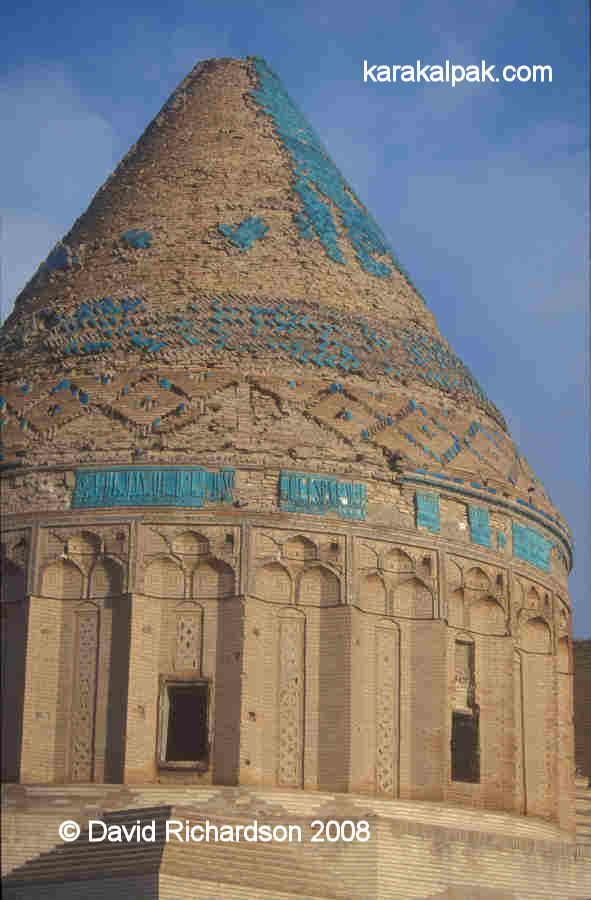

Built of light yellow fired brick, the foundations of the monument currently lay several metres below the level of the surrounding landscape. The lower

part of the building consists of a massive square-shaped chamber with outside walls that are 19-metres long on each side and over 3 metres thick.

Right: plan by I. I. Notkin, 1989. Left: section by N. M. Bachinski, 1989.

It has a rectangular portal on its northern side and arched windows on its other three sides. The portal is rather squat compared to that on the later

Tura beg Khanum Mausoleum and, for example, the medressehs of Samarkand. The arched entrance contains an unusual conical shaped muqarnas with

corbelled vaulting. Architectural historians describe its style as Seljuk. The doorway leads directly into the chamber. Spiral staircases on either

side of the entrance provide access to the portal roof.

The damaged portal photographed by A. Yu. Yakubovsky in 1928.

This part of the building was very badly damaged in the past and in 1983 work began to completely restore its structure. It now has a rather brutal and

featureless appearance, making it hard to imagine what the original building was like.

The square chamber supports a cylindrical drum with a 24-sided polygonal outer surface and an octagonal centre. It contains six evenly spaced

rectangular windows and internal semicircular niches with shell-shaped baroque-like decorations. The external sides of the drum were decorated with

elongated niches topped with trilobate squinches, once decorated with sophisticated tile work. The niches are separated from each other by triangular

columns.

The cylindrical drum and conical roof.

The badly damaged roof decoration, prior to renovation.

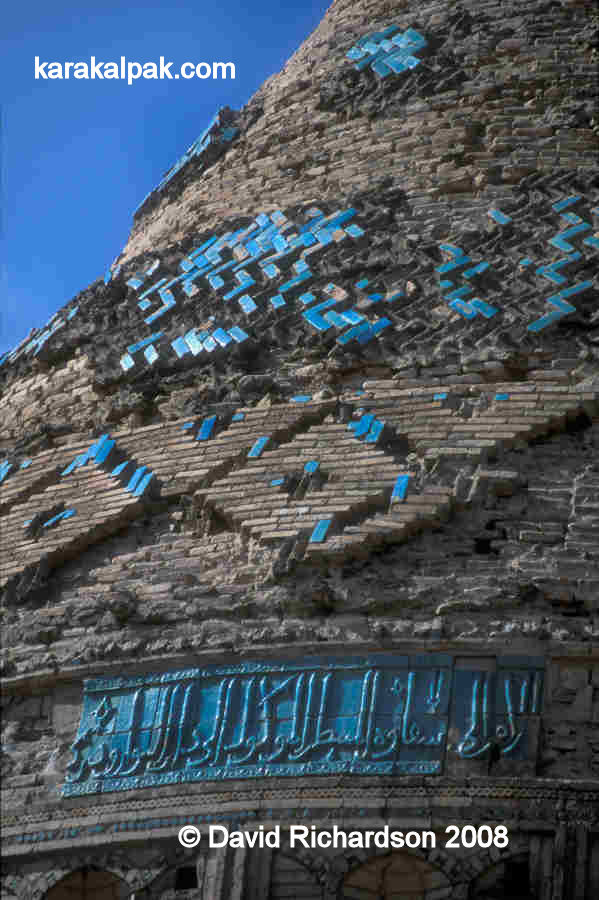

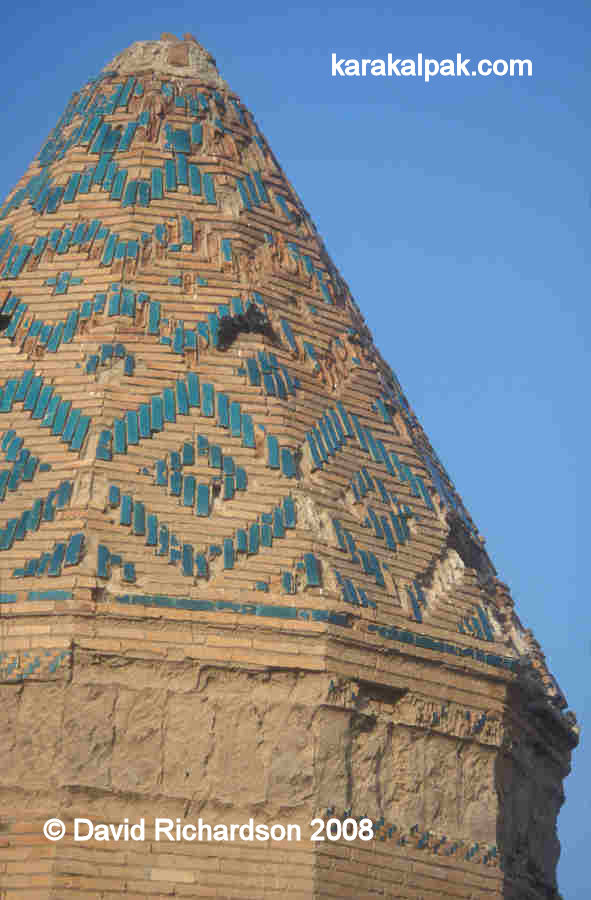

The building's greatest feature is its magnificent conical hipped roof. The top portion of this is covered with rectangular-shaped bricks laid out in

a herringbone pattern, the outer face of each brick having a turquoise-coloured glaze. The lower section of the cone is decorated with a wide band

of similar bricks arranged as a repetitive pattern of large diamonds. Just below the hip of the conical roof is a frieze composed of large moulded

turquoise-glazed tiles bearing a Kufic inscription.

Part of the Kufic tiling below the hip of the conical roof.

In its original state the roof must have looked spectacular. In 2005 the roof remained in a

critical condition with many glazed bricks already lost and others becoming detached. In 2006 the outer shell of the drum and roof was restored

thanks to a grant from the US Department of State.

Work beginning of the restoration of the roof in 2006.

The conical roof conceals an inner dome decorated with small holes forming the outline of a 12-pointed star.

Once again the purpose of the building and its date of construction remain a matter of opinion, of which there are many. There is recent evidence to

suggest that it was the central building or the major component in a much larger complex. This may explain the featureless square base, whose walls may

have been once concealed by surrounding buildings.

The Sultan Tekesh Mausoleum was not a free-standing building.

The attribution of the building to the Khorezmshah Sultan Tekesh (reigned 1172-1200) seems to be the most widely held view among Russian and Central

Asian architectural historians. They believe it was part of a combined mausoleum and funeral mosque, especially given the existence of a structure

which may have been an underground tomb adjacent to its western side. There is some historical support for this point of view. One written source -

Ibn al-Athir - noted that Tekesh constructed a complex in his capital city of Urgench containing a large medresseh and a tomb in which he was buried.

Meanwhile the Sultan's vezir, Ibn Ali al-Kharavi recorded that Tekesh built a huge medresseh, mosque and manuscript library. It is not known

whether these two complexes are one and the same, or whether either of them relate to the current building.

An alternative theory has been proposed by the Berlin-based Professor Sergej Chmelnizkij, who thinks the building was not a religious structure at all

but the audience chamber of the Palace of the Khorezmshah.

Both the above theories place the date of construction in the late 12th or early 13th century, just before the Mongol conquest. We do get some help in

deciding between them from the 13th century writer Juzjani, who noted that only two edifices remained in the city of Gurganj following the Mongol

conquest: the Kushk-i Akhchak [Kyrk Molla] and the mausoleum of Sultan Tekesh.

Clearly more investigative research is required.

Kyrk Molla

Kyrk Molla is a semi-circular hill located about 150 metres to the north east of the Tekesh Mausoleum. It is about 150 metres from north to south and

100 metres wide. It is about 200 metres west of the rampart of the Golden Horde city. The current Turkmen name means "forty mullahs". During the era

of the Golden Horde it was known as the Kushk i-Akhchak or Castle of the Akhchak.

Kyrk Molla in 2003.

In 1991 extensive excavations on the western side of the hill supervised by Kh. Yusupov revealed the foundations of a defensive mud-brick wall,

reinforced with rectangular towers shaped like a truncated pyramid. Finds of ceramics date the earliest occupation of the site to the 4th and the 3rd

centuries BC. At that time its location was probably close to a bend in the early Darya Lyk river the old snake-like course of the Amu Darya at a

time when it flowed west towards the Caspian Sea. Such a location would have been optimum for agriculture since it required less investment in

irrigation works. The early city seems to have been occupied into the early Middle Ages, the so-called Afrigid feudal era, since its upper layers

contained a rich assortment of ceramics from this period.

Kyrk Molla before and after the construction of the modern defensive wall.

Thanks to a UNDP grant the external fortified wall has been partly reconstructed using modern mud brick and plastered with adobe. Openings have been

left in the new wall to show some of the original brickwork. The whole development looks an eyesore.

A human jaw and arm bone on the western flank of Kyrk Molla in 2001.

Before the construction of the new wall, the western side of the hill was littered with the remains of human skeletons. Local guides used to brag that

this was the site of the city's stand against the Mongols. In fact the bones were the much more recent remains of local people who had been buried on

the hill of Kyrk Molla, which was regarded as a special holy site.

Mausoleum of Fakhr ad-Din Razi

The pretty little mausoleum attributed to Fakhr ad-Din Razi lies about half a kilometre south of the Kyrk Molla hill.

.

This too is built from light-yellow fired brick and has a cubic base supporting a 12-sided drum which in turn supports a conical dodecagonal (12-sided)

hipped roof. Excavations have shown that the ground level of the mausoleum is several metres below the current ground level, meaning that the

original building was once considerably higher.

.

The east-facing front of the cubic base is richly decorated. It contains three rectangular niches, each containing arched structures. The central

arch contained a lower door and might, along with the outer arches, have contained rectangular windows. The spaces within the upper parts of the

arches and surrounding the upper parts of the arches are filled with carved decorative brickwork, while the three rectangular niches are bordered by

a frame of calligraphic inscriptions. It is possible the base once had doors on all four sides.

.

The 12-sided drum contains four rectangular windows. It was once decorated around its summit with a wide frieze but today the tiles are all missing.

The conical roof is covered with glazed and unglazed bricks arranged to create a pattern of interlocking concentric diamonds. The interior of the

chamber is undecorated and contains a simple domed roof.

The building cannot have been built as a mausoleum for the Persian theologian Fakhr ad-Din Razi, since he only spent a short part of his career as a

religious teacher in Gurganj, where he was favoured by the Khorezmshah Tekesh. However he was soon expelled for his controversial views and eventually

died in Herat in 1209/1210, where he was buried.

.

The building is generally considered to have been constructed in the second half of the 12th century. Because of this, people have speculated that it

might have been the mausoleum of the Khorezmshah Muhammad's grandfather, Il-Arslan, who died in 1172, or his great grandfather, Atsyz, who died in 1156.

The absence of a mihrab shows that it cannot have been a mosque.

In our opinion it seems to be a little too small to have been the mausoleum of a great Khorezmshah.

The Ma'mun Minaret

The foundations of the Minaret of Ma'mun lie 270 metres due south of the Mausoleum of Fakhr ad-Din Razi. This minaret seems to have collapsed at the

end of the 19th century. When Henry Lansdell visited the site in 1885 there were two standing minarets. He wrote that the westerly minaret was about

80 feet in circumference but was in a precarious state and surrounded by bricks. The eastern minaret, which was in better condition, was higher and was

114 feet in circumference. When Ole Olufsen visited the site in 1899, only one minaret was standing.

The attribution of the minaret to the Khorezmshah Ma'mun ibn Ma'mun (ruled 1009-1017) comes from a lead plaque inscribed with four lines of Kufic script

that was discovered in the ruins by local people in 1900 and is now held in the State Museum of History in Tashkent. The translation of the

inscription reads:

"The amir, the sayyid, the just prince Abu'l-'Abbas Ma'mum ibn Ma'mun Khorezmshah ordered the construction of this minaret. He constructed it himself

and supervised the laying down of the foundations, in humility toward religion and to approach God, may His mention be great, and with the desire for

recompense in this world and the hereafter. This took place in the year 401 [1010/1011 AD]."

This suggests that Ma'mun II funded the construction of the minaret himself and regarded it as an investment rather than a charitable deed.

Excavation of the foundations of the minaret in 1952.

The foundations of the collapsed minaret were discovered below a hill excavated by Sergey Tolstov and his colleagues in 1952. The minaret was only

preserved up to the level of a marble ring. Tolstov also discovered the remains of the associated mosque, which had floors laid with fired bricks and

stone pyramid-shaped bases for the columns that once supported the roof. Tolstov believed that the early medieval mosque and minaret had been destroyed

by the Mongols and were then restored in the 14th century at approximately the same time that the Qutlugh Timur minaret was repaired.

Tolstov's excavations were rediscovered in 1993. In 1999-2000 the minaret was partially reconstructed on the original foundation up to a height of

6 metres above ground level.

Gate of the Caravanserai

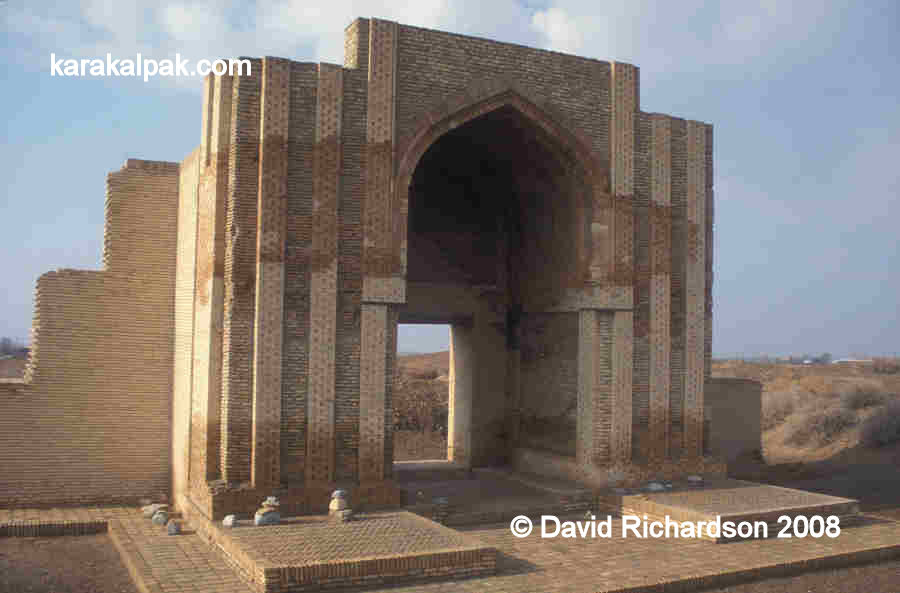

The so-called Gate of the Caravanserai is a free standing archway that may have been the lower half of a larger portal. It is located in the southern

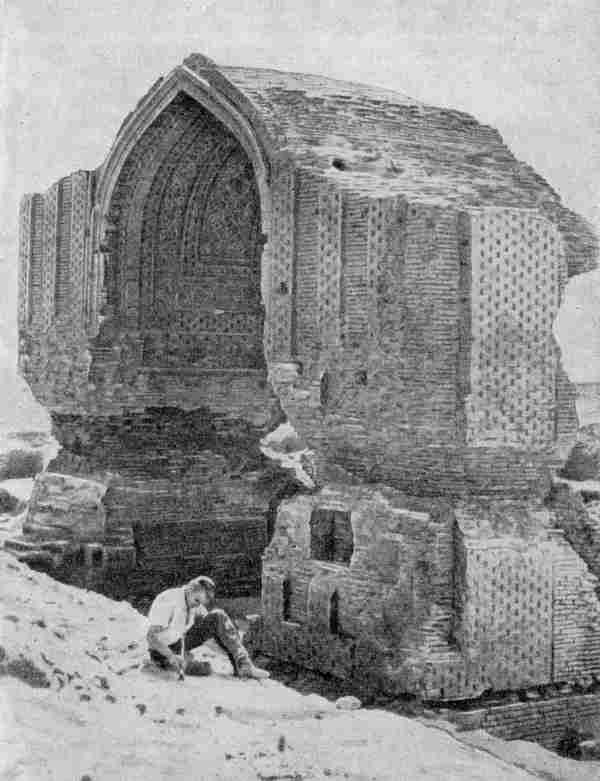

part of Tash Qala not far from its main thoroughfare. At the time of its excavation by Tolstov in 1952 it was extremely badly damaged, with much of

the top missing and the sides badly eroded by the salty damp soil. It was partially restored in the 1980s but was almost completely rebuilt in

1999-2000, when huge buttresses were added on either side to prevent its collapse.

Following the excavations by Tolstov in 1952.

The Gate of the Caravanserai in 2003.

The gate was built of light-yellow fired brick and contained a pointed arched opening. There is no muqurnas or squinch like that on the

entrance portal of the Tekesh Mausoleum. The face of the portal is decorated with three vertical rectangular columns on either side of the opening,

decorated with carved bricks. The only surviving area of tiled decoration is confined to the inside surfaces of the archway and utilizes a combination

of terracotta tiles and dark blue, light blue and white glazed mosaic tiles. A central panel of interlocking roundels with floral mosaics is surrounded

by a border of interwoven plaits forming patterns of squares enclosing star-like crosses. This style of tile work has been dated to either the late

12th or the early 13th century.

Decorative tile work on the inside surfaces of the arch.

It is clear that such a grand portal can never have been the entrance to a caravanserai as Yakubovsky initially assumed. Although there was a nearby

caravanserai, V. V. Zotov established that it was built at a later date than the portal itself. The latter must have been the entrance to a public

monumental building such as a mosque, medresseh or palace.

One unlikely theory is that it was the entrance to the late 10th century palace of the Khorezmshah Ma'mun I. However the foundations of the gate rest

on pre-Mongol layers containing distinctive 12th century ceramics. These were produced by a recently introduced firing process involving chemical

reduction and are quite distinct from the ceramics that were made during the earlier 10th and 11th centuries. Furthermore we know that the Palace of

Ma'mun was close to the Hajjaj Gate, which Yusupov has convincingly shown to be the northern gate of the city. The Gate of the Caravanserai is of

course in the southern part of the city.

After all these years, the function of the gate still remains a mystery.

Link

To see the 2004 Government of Turkmenistan nomination for UNESCO World Heritage Site status

click here: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1199/documents/

Google Earth Coordinates

The following reference points (in degrees and digital minutes) will enable you to locate the different monuments at Kunya Urgench on Google Earth:

| | Google Earth Coordinates |

|---|

| Place | Latitude North | Longitude East |

|---|

| Tura beg Khanum Mausoleum | 42º 18.674 | 59º 8.231 |

| Seyit Akhmet Mausoleum | 42º 18.589 | 59º 8.356 |

| Qutlugh Timur Minaret | 42º 18.521 | 59º 8.515 |

| Sultan Tekesh Mausoleum | 42º 18.445 | 59º 8.633 |

| Kyrk Molla Hill | 42º 18.516 | 59º 8.767 |

| Mausoleum of Fakhr ad-Din Razi | 42º 18.269 | 59º 8.739 |

| The Ma'mun Minaret | 42º 18.120 | 59º 8.738 |

| Gate of the Caravanserai | 42º 17.864 | 59º 8.728 |

| Aq qala | 42º 17.785 | 59º 9.125 |

| Khorezm Bag | 42º 17.839 | 59º 7.917 |

| | | |

Note that these are not GPS measurements taken on the ground.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|

|