The Karakalpak Sa'wkele - Part 2

|

The Karakalpak Sa'wkele - Part 2

|

|

ContentsPart 1The Sa'wkeleStructure and Design Materials Ceremonial Use Part 2Sa'wkeles in MuseumsThe To'belik Qazaq, Kyrgyz, Uzbek, and Turkmen Headdresses Other Central Eurasian Headdresses Part 3Mythology of the Sa'wkeleOrigin of the Sa'wkele Conclusions Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms References Sa'wkeles in MuseumsThere are supposedly only seven sa'wkeles in the museums of the world, along with just two to'beliks. According to Galiullina five of those sa'wkeles and one to'belik are in Saint Petersburg. In addition there are just two sa'wkeles and one to'belik in No'kis. Although we have seen both to'beliks we have only seen four out of the seven sa'wkeles, two in Saint Petersburg and two in No'kis. The No'kis examples show the contrast between unrestored and restored sa'wkeles and were both well displayed for all-round viewing. Unfortunately the unrestored sa'wkele is no longer on display since the closure of the Museum of Regional Studies. It is to be hoped this situation is soon remedied.Savitsky State Museum of Art, No'kisThe State Museum of Art named after Igor Savitsky has a sa'wkele (inventory number 5971) and a to'belik (39751) on public display, both fully restored. All of the illustrations in Part 1 relate to this particular sa'wkele, which we photographed at the museum in 2004.According to the report of Galiullina, the Laboratory of Folk Art at the Karakalpak Branch of the Uzbek Academy of Sciences in No'kis had been looking for a sa'wkele for several years before they came across this example. She reported that it was acquired in 1961 from the home of G. Allambergenova from Tog'ızterek near Qazaqdarya. According to the owner it had belonged to her mother, and possibly also to her grandmother. At that time it was in a very decrepit state. The records of the Savitsky Museum show that it was indeed bought from Gu'lziry Allambergenova but that she actually lived in the tiny awıl of Tog'ız to're (meaning nine masters or senior people). It lies close to the settlement of Zayır on the right bank of the Amu Darya in Bozataw region. At that time it was a part of the sovxoz named "Qazaqdarya". The Aral crisis has transformed this region into a barren desert and today it can only be reached in a four-wheel-drive vehicle. The museum estimates that the sa'wkele dates from the mid-19th century. In 1968 it was transferred from the Karakalpak Branch of the Uzbek Academy of Sciences to the State Museum of Art and Igor Savitsky decided that it should be restored. It was sent to the Central State Art Restoration Workshop named after Grabarya in Moscow, where it was restored by Margaret Riabova and Tatyana Goroshko. The work was completed over a period of 18 months with no input from No'kis.

Sa'wkele 5971.

|

|

Despite the restoration the tumaq still possesses a significant amount of its original ushıga, although most of

the qızıl ushıga has lost its nap. Fortunately this reveals the underlying plain weave of the textile.

Although the ushıga has been moulded to follow the contours of the rounded cap, the weave structure does look very even

suggesting that the original ushıga was indeed machine-woven rather than handmade.

|

The jıg'a is circular with a star-shaped outer edge set with small coral and green turquoise stones. At its centre is a gilded conical

setting with fine punched patterning holding a single pink coral stone fastened through its middle by a small metal decorated pin. The

qıran are stylistically quite different from the jıg'a, depicting two creatures in mortal combat. The lower figure

resembles a mountain goat with horns curling backwards, while the upper figure is the head of a bird of prey with a backwards curling head

feather (although it actually looks more like a horned deer or antelope!). The metal settings are gilded but have a silver outer edging.

The three linked chains of metal settings within each earguard have been made in a similar style, the conically raised centres being decorated

with horn-like scrolls.

|

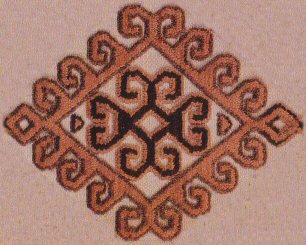

The embroidery on the tumaq is very simple with omırtqa or vertebrae motif used to cover the join between the red and black

ushıga, bordered with rows of simple repetitive floral and fork-like motifs, coloured red, white, yellow, and green. The

fork-like motif may represent the tamg'a of the Mu'yten tribe. The embroidery on the upper halaqa is more elaborate with a

geometric zigzag outer border bearing single curled horns (taq mu'yiz or odd horns) embroidered in raspberry red silk, rows of simple

three-pronged floral motifs, and a vertical central column of sun-like medallions.

For detailed information on visiting this museum see our Sightseeing page.

|

This sa'wkele was described by Morozova in her thesis, where she identified it by the inventory number 99:

"… Judging by the sample of the sa'wkele number 99 from the reserve collection of the Regional Museum of the KKASSR, the appearance of the sa'wkele was the following: the main felt part of the sa'wkele was covered with red broadcloth while its lining was made from a handcrafted textile with a stamped pattern "astora chit".This example has several similarities to the Savitsky sa'wkele:

Narrow black bands covered with embroidery were positioned on the red background of the sa'wkele. On the sa'wkele mentioned above, there was embroidery executed on narrow (5.5cm wide) black velvet bands sewn round the cap-band and a cross-shape on the top of the cap. Obviously the cross on the top of the cap underlines the contrasting combination of red and black colours. This is a characteristic feature of the Karakalpak sa'wkele that is also mentioned in T.A. Zhdanko's work "Karakalpaks of the Khorezm Oasis".

The earflaps were decorated with thick rows of corals threaded on silk, which were sewn on above the two narrow patterned strips of red broadcloth; sewn parallel to each other (the first strip was at the earflap edge and the other one was a little bit further from it).

Various forms of small metallic plates with carnelian were sewn on between the corals.

The embroidered halaqa at the back of the headgear was very extraordinary.

All halaqas of sa'wkeles from the Karakalpak Regional Museum consist of three wedge-shaped narrow strips, which are sewn together in the upper narrower part and separated at the end. ..."

|

However it also has certain differences, mainly associated with the jewelled forehead and ear covers. The coral beads forming the forehead

cover are held by a lattice of metal wire which incorporates three horizontal rows of conical alloy settings holding stones of coral and green

turquoise, many of which have been lost. This is more like the decoration on the front of a to'belik and one wonders if the Regional

Studies sa'wkele has been made up from the remnants of an earlier pair of sa'wkele and to'belik?

The simple jıg'a is smaller and hangs down between the eyes. The qıran are much corroded and though oriented in an

upright position are unusually set to the back of the ear flaps, almost as an afterthought. They are very similar in appearance to those on

the Savitsky sa'wkele, each depicting the head of a bird of prey positioned above a horned mountain goat. A second pair of

qıran has been attached to the front sides of the tumaq. It is as though they have been rescued from another

sa'wkele and have been added to this one for additional embellishment. There is minimal embroidery on the tumaq and an

edging of fur has been sewn around its bottom. The lower part of the halaqa is divided into two sections rather than four.

For detailed information on visiting this museum see our Sightseeing page.

|

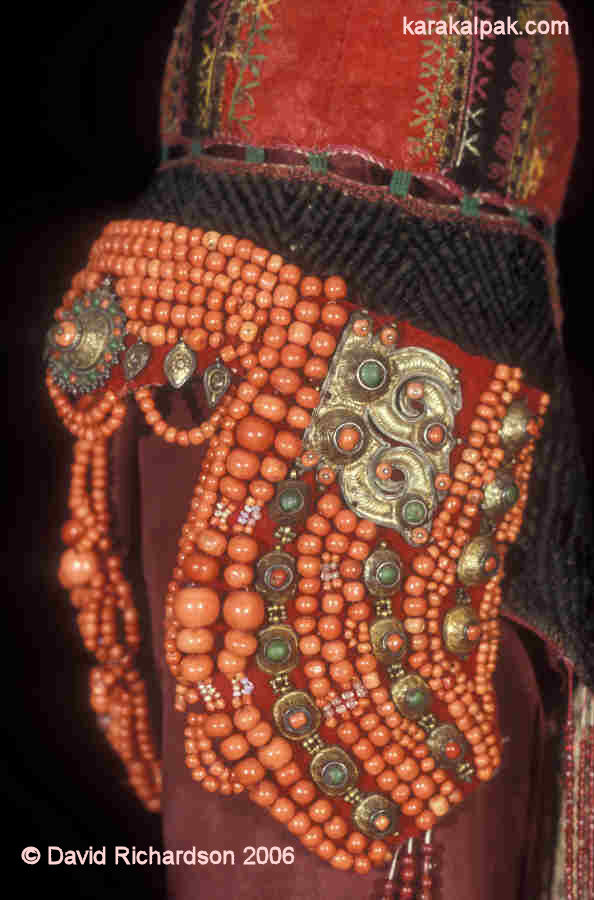

The forehead and ear covers are covered with strings of pink coral beads supported by a lining of red bo'z. The forehead cover has

just a lower horizontal row of small tear-shaped metal plates, which conceal the fur edging of the tumaq. A square-shaped bejewelled

jıg'a is positioned in the centre and shares many features with its Savitsky equivalent - a star-shaped outer edge set with small

coral and green turquoise stones, many of which are missing, and a raised conical setting holding a single coral bead with a small metallic

decoration at its centre. The ear flaps contain several vertical chains of conical metal settings and a pair of qıran. As with

the Savitsky example, some of the strings of coral towards the front part of the ear flaps contain short strings of small pearl-like beads.

The qıran are fastened on upside down and as before depict the head of a bird of prey above the head of a mountain goat.

|

The halaqa consists of an upper and lower section, each lined with a different type of hand-printed bo'z.

The lower section in this case is embroidered in just a single raspberry red colour.

|

Strings of pomegranate-coloured boydası hang down from either side of the halaqa at the back, as do two necklaces strung

with a mixture of beads of varying sizes and materials, including glass, stone, quartz-chalcony, and bronze.

|

The forehead cover and earguards are not constructed as an integral whole and appear to be additions. The forehead cover is a rectangle

of qızıl ushıga with five horizontal rows of small coral beads running along its top, a row of brown fur sewn

along its bottom edge with a square-shaped jıg'a affixed at its centre. The earguards have been very crudely made. They are quilted

with an outer covering of bright red woollen cloth that appears to be of a much more recent age than the rest of the headdress. Three vertical

chains of conical metal mountings incorporating blue turquoise and coral stones have been attached to each earguard, some of them separated

by crudely attached vertical strings of small coral beads. It has only one qıran plate attached to its right-hand side, above

and to the front of the ear flap in an upside down position.

|

The lower back of the tumaq has a rectangular patch of brown felt, from below which hangs the upper part of the halaqa.

This is paddle-shaped with a black centre and a red outer border. It has been embroidered with repetitive rows of simple motifs: chevrons,

diamonds, stylized single stem plants, and three-pronged fish spears, the latter being the tamg'a of the Mu'yten tribe. The museum

literature refers to the presence of motifs representing a four-armed goddess, "a characteristic of the Aral area". We know of no such

Karakalpak embroidery motif. The motif referred to is probably the trident fish spear. Images of the goddess Anahita have been found on

Khorezmian silver dishes and ossuary dating from the 6th to the 7th centuries, showing her as a four-armed goddess holding images of the sun

and half moon. However we find it impossible to connect the pre-Islamic culture of Khorezm to 19th century Karakalpak folk art.

|

The lower part of the halaqa is sewn to the underside of the upper part and is composed of two lengths embroidered in basma technique

with a sequence of raspberry red cog-shaped roundels on a green and yellow background.

Approximately ten strings of pomegranate-coloured and other beads are fixed behind each ear guard. There is no separate necklace.

|

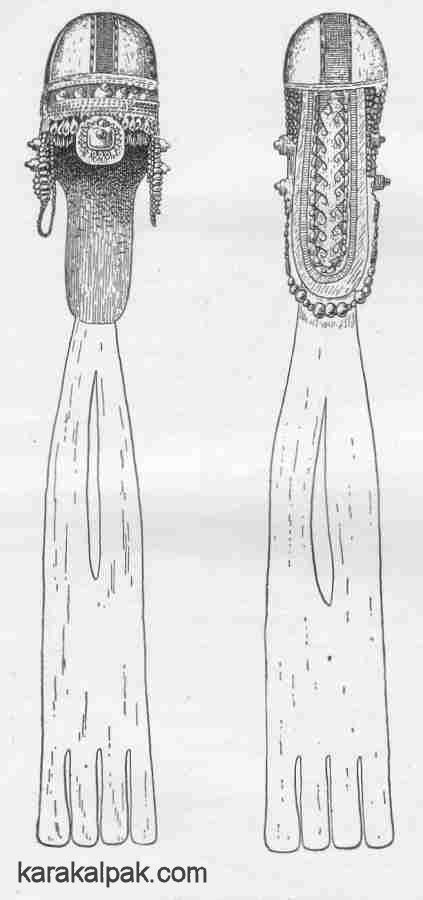

The first is the hand-drawn illustration used by Zhdanko herself in her first 1952 article and reproduced by Morozova. This may have been

the image used to encourage a response from elderly Karakalpaks during field visits in 1947. It is not clear whether it is an artist's

impression or the depiction of an actual sa'wkele, since it differs from all other known examples.

|

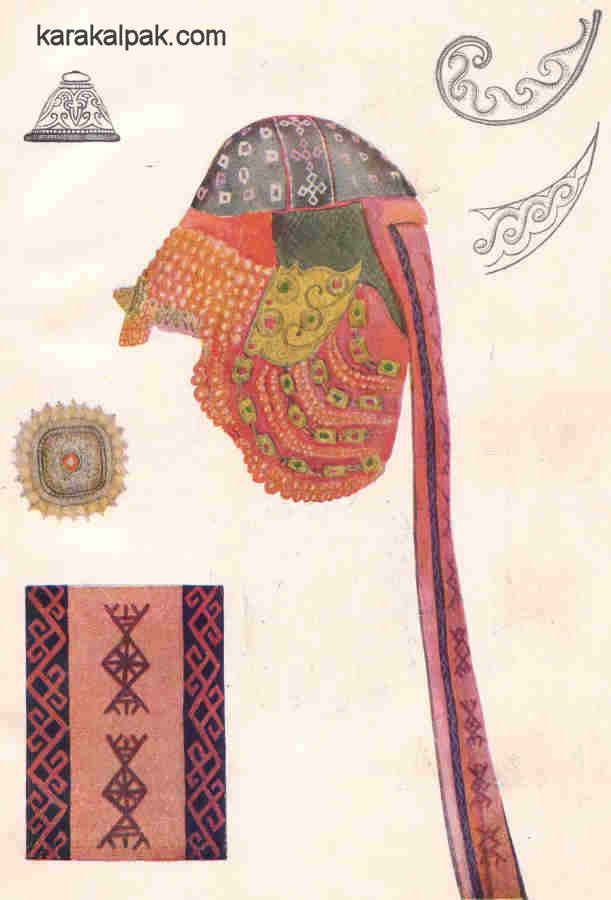

The second is a coloured illustration from a collection of plates published by B. V. Andrianov and A. S. Melkov in 1958. This example is quite

distinctive, having a low skullcap-shaped tumaq, decorated as usual with a black cross but in this case on a background of black

ushıga rather than red. The qıran is upside down and the rear halaqa has an unusual embroidery motif.

There is no indication of a peacock's tail.

|

The third example is an illustration of a sa'wkele referred to as belonging to the State Museum of Ethnography of the Peoples of

the USSR in Leningrad by Sazonova et al in 1961. It was one of 175 items collected during the period 1928 to 1938 by individuals

such as Davlet, Melkov, and Tolstov. It is not the sa'wkele currently owned by the Russian Ethnography Museum in Saint Petersburg.

Finally we should mention that Lobacheva referred to a sa'wkele from Tasbesqum Island, Taxta Ko'pir region, which was owned by a

member of the Mu'yten-Ken'tanaw clan. The top was made from thin layers of cotton, covered with small lines of stitching. The owners

referred to it as a taqıya.

The To'belik

The two known to'beliks are very similar to each other.

|

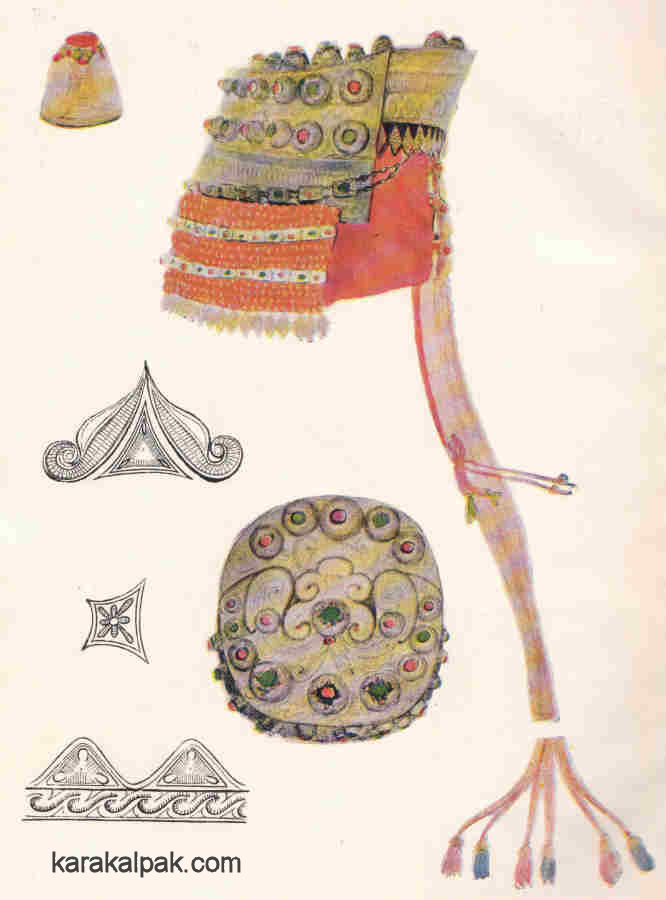

The Savitsky to'belik, inventory number 39751, originally came from the Regional Studies Museum. At the time of its acquisition

75% of the original headdress had been lost. Igor Savitsky sent it to Moscow for restoration, a task that took 13 years. It is possible

that it was modelled on the example already held at the Museum of the Peoples of the USSR in Moscow. The restorers could not find a place

to attach the fur fringe and also added a red plait cover, although none was present prior to restoration.

|

The top section of the to'belik is made from three metal plates: a flattish top, a semi-circular front, and a semi-circular back all

held together by small ring-like fasteners. They have been decorated with patterns using a metal punch and have then been gilded, except for

the lower section of the front plate, which has been silvered. The front plate has rows of semi-circles and flowers and a line of wave-like

curls. The top and the front plates also have rows of conical settings with spiral decorations, each holding a semi-precious or glass stone

– mainly turquoise-coloured glass and a few pink corals. In between there are round coral beads that have been riveted in place by metal pins

that pass through their centres. The back is relatively plain but has a lower row of oval lobes and is backed by a stiff red fabric. Identical

chains of equal length containing coral beads and three tear-shaped metal platelets hang from the bottom edge of this fabric like a curtain.

|

A second jewelled curtain is suspended across the lower front of the to'belik, its two upper corners fastened to the lower outer edges

of the back plate. It consists of a horizontal chain of gilded conical settings, each holding a stone: green turquoise, turquoise-coloured

glass, coral, or carnelian. Vertical chains descend from each setting, each containing two further conical settings with stones and a lower

tear-shaped platelet. Each of these components is separated from its neighbour by a round coral bead.

A long plain maroon red plait cover trails down from the back.

|

The Hermitage to'belik is constructed in exactly the same manner. It too is decorated with wave-like curls and the conical settings are

decorated with spirals. Although hard to see in the museum, the top plate has a somewhat Arabesque decoration of winding plant stems. The

precious stones seem to be far more complete, composed of mainly green turquoise and coral without any glass replacements. The main difference

occurs in the construction of the jewelled curtain suspended at the lower front, which contains three times as many coral beads as the Savitsky

to'belik, giving it a fuller appearance.

Qazaq, Kyrgyz, Uzbek, and Turkmen Headdresses

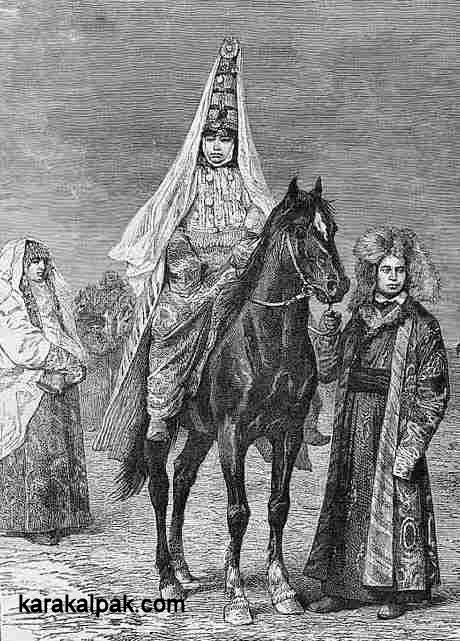

Whereas the Karakalpak sa'wkele was helmet-shaped, the Qazaq sa'wkele was tall and conical. It consisted of two main parts:

a conical cloth cap with a quilted lining no more than 25cm tall, sometimes incorporating a forehead cover or a rear neck cover, and a taller

reinforced conical sheath with a diagonally truncated top, usually covered with red felt and decorated on the outside with corals, semi-precious

stones, silver platelets, and braids, with a lower edging of fur. Strings of coral, turquoise, metal plates, and tassels were suspended from

either side reaching down to the stomach. Finally a large cloak, called a jaulyk, of light cloth such as white silk or muslin

decorated with embroidery, was fastened to the top and hung down over the shoulders, enclosing the wearer's body. Like the sa'wkele

it was worn by the brides of aristocratic tribal leaders and was particularly fashionable during the second half of the 19th century.

|

Styles varied between the three Hordes and by region. There are two fine examples in Saint Petersburg, the first in the Hermitage Treasury and

the second in Peter the Great's Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography. The latter sa'wkele, inventory number 439-21, was donated to

the museum in 1899.

|

|

Some Qazaq married women wore a more conservative, white-coloured aq sa'wkele after they were married. There was also an alternative

headdress for the Qazaq bride known as a kasaba, which seems to have become less popular during the 19th century. It was cylindrical,

made of red velvet, and was richly decorated with gold embroidery, semi-precious stones, beads, and medallions. Strings of platelets and beads

with tassels hung down over the ears and the top was decorated with a cluster of birds' feathers.

|

The Kyrgyz shukulu was closer to the Karakalpak sa'wkele. It consisted of a conical helmet, 25 to 28cm tall, which was quilted

and ribbed with vertical stitches. It had large rectangular ear flaps and a triangular-shaped plait cover at the back, up to 45cm long. The top

was finished with feathers from a peacock, pheasant, or crane. The outside was richly decorated with pearls, mother-of-pearl, silver and gold-plated

figurines, brocade, and a net of small coral beads. Sometimes gilded plates known as kalkan were fastened to the sides. Such headdresses

were mainly in use during the second half of the 19th century and were restricted to the wealthy. The less expensive helmet-shaped

kep takyya became popular during the late 19th century, especially among the Pamiris. This was made from home-made cotton, had

ear covers and a long plait cover, both of which were elaborately decorated with raspberry red embroidery patterns. The top was left open and

undecorated, being pulled together by a draw string and then covered by a white cotton turban.

As already mentioned the Aral Uzbeks had a sa'wkele very similar to the Karakalpak sa'wkele. However the Khivan Uzbek bride

wore a somewhat different headdress for the wedding ceremony during the 19th century. On her head she wore a high pointed cap called a

chumakli tax'ya made from silk alacha with a red and black stripe. This was quilted with a layer of soft cotton and had an

inner lining of white bo'z. Although the cap was tall and conical it was actually worn squashed down with two folds. The

tax'ya was then decorated with a set of jewellery known as a shevkele or shevkeli. This was a somewhat tiara-like

headdress, with a metallic front and two metal side plates, both engraved with filigree, gilded and studded with semi-precious stones, and

both supporting vertical strings of small beads and metal platelets from their lower edges, which covered the forehead and the sides of the

head down to the shoulders. The shevkele has a clear resemblance to the forehead and ear covers of the sa'wkele.

The Khivan Uzbeks also had a headdress resembling the Qazaq kasaba. An example exhibited in the Islam Xoja Museum in Khiva is

listed as a tax'ya duziy. It is a woollen cylindrical skullcap with a circular silver plate attached at the top, the latter set

with carnelians and edged with small turquoise stones. A bunch of feathers sprout from the top. A multitude of chains are suspended from

the edge of the circular plate, fanning out to cover the sides of the tax'ya, each one strung with coral beads, gilt platelets, and

other semi-precious stones.

|

The headdress of the Yomut Turkmen located near the mouth of the Atrak River was first decribed by Nikolay Muravyov in 1819. He compared it

to the Russian kokoshnik (see below), except that it was two or three times as high. Among the wealthy the headdress was edged

with gold or silver. The hair was visible on the forehead, but was combed "modestly off on either side and plaited into a long tail behind".

Other 19th century travellers, such as E. Eichwald, Ivan Fedorovich Blaramberg, G. S. Karelin, and P. P. Ogorodnikov, referred to the Yomut

headdress as a khasava and noted that the front was decorated with gold plates and silver coins.

|

The examination of 20th century examples of the headdress used for the wedding of a northern Yomut Turkmen bride shows that it contained some of

the elements found in the Karakalpak sa'wkele, although structurally it was quite different. It was constructed in situ on the

head of the bride, starting with an underlying wooden framework known as a borik. This was wrapped in home-made silk and a silk shawl

was suspended from the back. A sinsileh or chain of hanging silver plates was fastened horizontally along the top of the headdress and

a forehead cover or manlayik was attached below it. Finally pendants known as tenechir are hung on either side, framing the

face. A richly embroidered black or green silk chyrpy with false sleeves was draped over the top of the headdress to complete the costume.

Russian ethnographers have reported that the female headdress of the Chodor Turkmen was different, being very similar to the sa'wkele.

In the 19th century the Chodor were settled on the western edge of the Aral delta.

Other Central Eurasian Headdresses

Female headdresses with features similar to those found among the Karakalpak, Qazaq, and Kyrgyz also occur among many of the Turkic, Slav, and

Finno-Ugric Tartar peoples living in what is today eastern Russia, inhabiting the region stretching from the mouth of the Volga northwards to the

southern Ural Mountains and Siberia. Married women wore richly decorated helmet-shaped or conical headdresses with long plait covers, while

unmarried girls tended to wear decorated skullcaps very similar to the Central Asian tax'ya. In general the hair was always plaited,

young girls having many plaits but married women having just two.

Among the Turkic tribes were the Noghay, Kazan and Crimean Tartars, Bashkirs, and Chuvash. Among the Finno-Ugric tribes were the Mordvins,

Mari, and Udmurts.

|

In the lower Volga, Noghay brides wore a tall headdress covered in red felt with a rounded top. It was covered with either Turkish coins or silver

plates set with semi-precious stones and had chains of beads and silver platelets suspended from each side. The Tatars of Kazan, meanwhile, wore a

pointed helmet-shaped headdress covered with metallic plates with a long plait cover attached at the back, reaching down to the calves.

|

North of Orenburg, wealthy Bashkir married women wore a helmet-shaped headdress called a kashmau, which completely covered their hair.

The top of the cap was decorated with a grid of coral beads, coins, platelets, and included suspensions of chains, while an occipital plait cover

was hung from the back, decorated with embroidery, beads, and cowrie shells. Suspensions on the front of the helmet reached down to the eyebrows,

covering half of the face. Some caps incorporated animal fur. Unmarried girls wore knitted and embroidered caps known as takyya.

|

Chuvash married women wore a similar khushpu, which could be of two types: cone-shaped or helmet-shaped. They were usually worn over

a surpan, a towel-shaped rectangle of linen. Both types of khushpu were made of canvas and were completely covered with red

and green beads as well as coins. They had a long narrow plait cover.

|

Young girls wore a tukh'ya, very similar to the Central Asian tax'ya. These also occurred in two forms, with or without a

pointed top, although both were covered with beads and coins.

|

Mordvin headdresses varied between the two main tribal groups, the Erza and the Moksha, and were called either a panga or a soroka

or sorka. They could be cylindrical, half-cylindrical, or conical and were made on a framework of white birch bark. They incorporated a

rear plait cover and were worn with one or more shawls.

|

The Mari or Cheremiss had three types of headdress: the shimaksh, a cone-like cap with a rear plait cover; the soroka, a corona

with a rigid rectangular top; and the sharpan, a turban-like head wrapping. They were all made from cloth and were richly embroidered.

|

|

The more northerly Udmurts or Wotjaks had a headdress known as an ayshon, which was tall and made from two pieces of half cylindrical

birch bark, one placed on top of the other and tilted forward. The whole assembly was draped with a rectangular cloth decorated with embroidery

and fringes.

|

Up to the end of the 19th century in the Smolensk and Vologodsk regions of Russia, married women wore a kokoshnik or a kokoshkhikov,

a tall round-topped birch-bark headdress wrapped in fabric, covered in metal plates and incorporating a kerchief.

In the Caucasus bejewelled helmet-shaped women's headdresses have been found in Azerbaijan. Tall conical headdresses made of metal are even

found among the Druze people of the Lebanon, who call them tantour.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

|

This page was first published on 12 September 2006. It was last updated on 25 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |