The Karakalpak Sa'wkele - Part 3

|

The Karakalpak Sa'wkele - Part 3

|

|

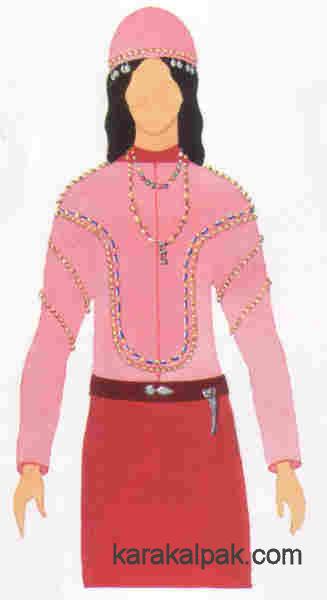

ContentsPart 1The Sa'wkeleStructure and Design Materials Ceremonial Use Part 2Sa'wkeles in MuseumsThe To'belik Qazaq, Kyrgyz, Uzbek, and Turkmen Headdresses Other Central Eurasian Headdresses Part 3Mythology of the Sa'wkeleOrigin of the Sa'wkele Conclusions Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms References Mythology of the Sa'wkeleIn the past there have been various attempts to link the material culture of the Karakalpaks to that of ancient Khorezm. For example, both Sergey Tolstov and Anna Morozova compared the sa'wkele headdress with the round helmet-shaped crowns of the Khorezmshahs depicted on ancient coins in the first centuries AD.

Sergey Tolstov's comparison between the crown of a Khorezmshah and the sa'wkele.

|

|

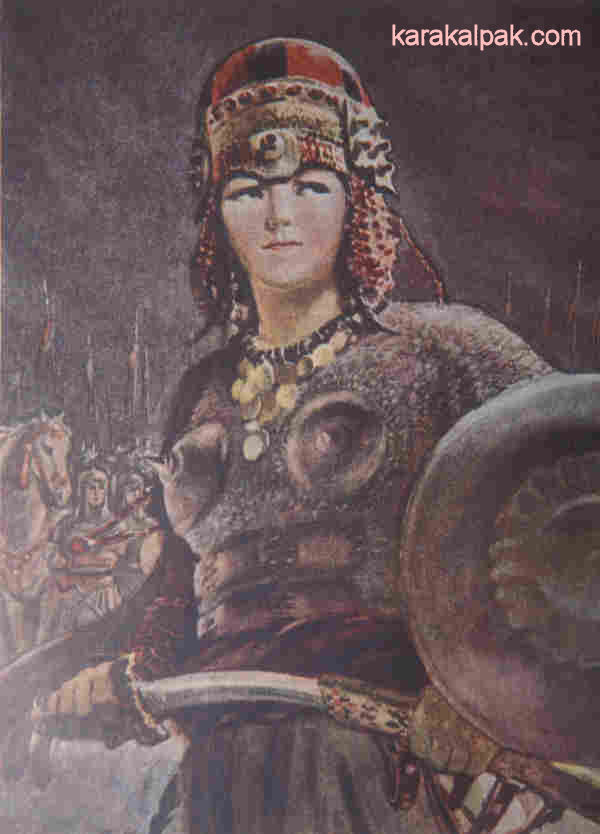

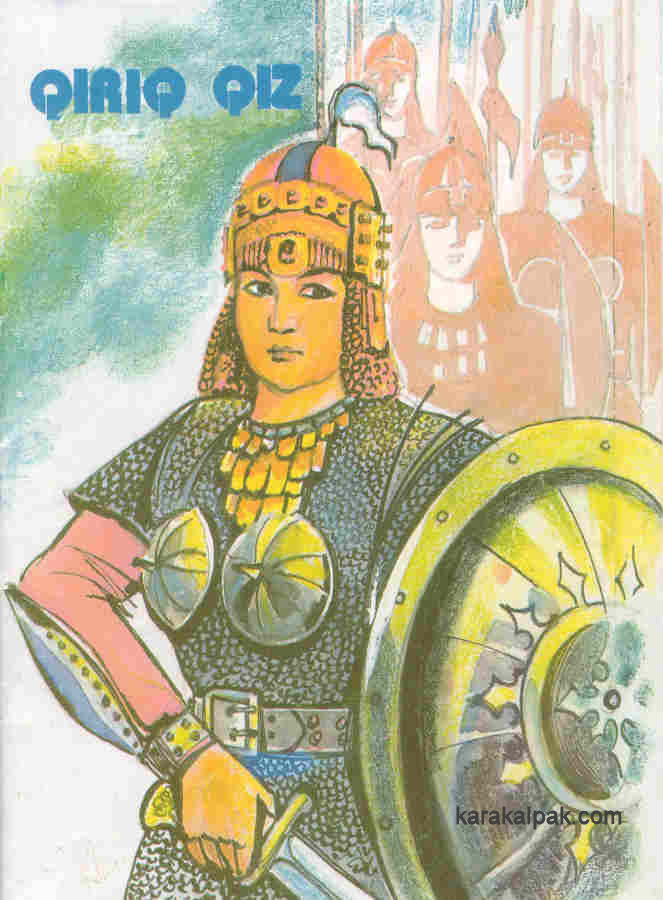

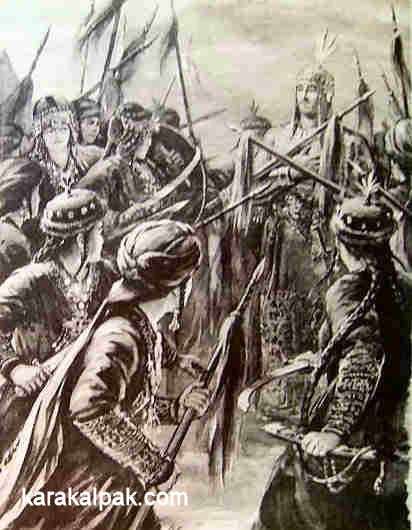

This association is enshrined in the Karakalpak epic legendary poem or da'stan "Qırq Qız" or "Forty Girls", which

is particularly associated with the coastal Mu'yten clan. The poem is based upon the Kalmuks or Jungars, warlike Mongol nomads who migrated

into the Volga region from Xinjiang in Eastern Turkestan just after 1600 and subsequently terrorised the Karakalpaks on the Syr Darya

during the 17th and 18th centuries.

|

The heroine of the da'stan is Gu'layım, the sixteen-year-old daughter of Allıyar, ruler of the Karakalpak fortress

of Sarkop. She is given the barren island of Miuyeli in the middle of the desert by her father and with the help of twelve masters builds

an unapproachable fort of her own, with high walls, metal gates, and a surrounding ditch. She is accompanied by forty virgin girls, who live

inside the fort in white yurts. Aware of the ever present threat of Kalmuk attack, Gu'layım trains her friends in military combat.

When not training they plough their island, transforming it into a fruit and flower-laden garden.

|

Her fears are finally confirmed when Surtaysh, the cruel Kalmuk Khan, attacks and captures Sarkop, killing her father and destroying the

surrounding Karakalpak lands in the battle. Hearing of the attack, Gu'layım dons her sa'wkele and rides off with her forty

friends to avenge the death of her father and the profanity wrought upon the Karakalpak people. After defeating Surtaysh in combat, she

becomes the ruler of her country and marries her sweetheart hero Arıslan.

|

Although this is a delightful story, it would be amazing if the Karakalpaks, a confederation of many different tribes with origins spread the

length and breadth of Eurasia, could have directly inherited the culture of the Saka-Massagetae tribes who had occupied the Aral region more

than two thousand years earlier.

The origin of the Karakalpak sa'wkele is much more complicated and uncertain. Although there is some linkage between the two cultures,

it is an extremely tenuous one.

The Origin of the Sa'wkele

Female headwear seems to have been an important indicator of status and wealth in many Eurasian nomadic societies. Unfortunately the historical

record is far from complete and there are major gaps. Nomads leave little record of their passing other than their burial sites and occasional

mentions in the records of neighbouring settled societies. To make matters worse costume design is a fickle thing, easily adapted to suit changing

tastes or external influences. It is therefore impossible to reach definitive conclusions.

The earliest uncontroversial evidence for the widespread use of spectacular female headdresses among nomads comes from excavations of Scythian

and Saka kurgan burials across the Eurasian steppes from the Black Sea to Siberia. It seems likely that they may have been inherited from earlier

Bronze Age kurgan cultures.

The Scythians appear to have radiated out from somewhere in the region of east Kazakhstan and southern Siberia, possibly the Altai, and were

probably descendants of the eastern Indo-Iranians. During the 10th or 9th century BC they began to spread out - to the west as far as the Danube,

to the south through Central Asia and the Caucasus, and to the east into Mongolia and China. The original Scythians spoke ancient Iranian, but

their culture spread to various other tribes who spoke Finno-Ugric, Turkic, and Mongolian languages. By the 8th century BC the Massagetae

confederation occupied the whole Aral region east of the Caspian Sea, while the Scythians occupied the steppes to the north of the Black Sea.

They were separated by the Scythian-speaking Sauromatians who pastured from the mouths of the Don and Volga to the southern Urals.

Scythian-Saka nomads shared a fairly uniform costume. From images depicted in Persian reliefs and on gold and electrum cups and beakers excavated

from Scythian kurgans we know that men (and possibly women) wore a felt cap with ear and nape covers. This is confirmed by the retrieval of

the actual items themselves from the Pazyryk site in the High Altai. Regional ethnic differences were conveyed through slight variations in the

cap's design - the Massagetae wore a pointed cap and consequently became known by the Persians as the Saka Tigraxauda – the Saka with pointed hats.

Evidence from kurgan burials also shows that certain Scythian women held positions of high status, taking part in military expeditions and

performing shamanistic functions. Herodotus recounted the defeat of the Achaemenid army of Cyrus by the Massagetae queen Tomyris. The Han-shu

chronicle commented that the Saka "hold the women in honour and what the women say they act upon."

In recent decades the painstaking excavation of kurgans across Eurasia has identified a multitude of Saka high-status female burials, many

associated with weapons and some with spectacular female headdresses. Most of the burials date between the 5th and the 3rd century BC.

They include:

|

None of the headdresses found has the faintest resemblance to a Karakalpak sa'wkele, but they do have similarities to the Turkmen

borik. Most are tall and have an inner structure of willow or birch twigs and a covering of cloth or felt, but there are considerable

regional differences. The Scythian headdresses from the Ukraine were cylindrical or conical, were covered with a large number of small gold

plates and bands, and had rear shoulder drapes.

|

|

|

|

Headdresses from the east tended to be black, tall and conical, and were appliquéd with carved wooden figures of horses, deer, griffins, and

snow leopards, all covered with gold foil. Some headdresses were embellished with feathers and pins and may have symbolized a tree of life.

However the Subeshi headdress was undecorated and the Pazyryk headdresses were quite different, one being made of wood with a pigtail of horsehair,

another made of leather and black coltskin covered with lozenge-shaped wooden carvings covered in gold foil and crowned with a diadem of cockerels:

|

Similar findings have been uncovered from the excavations of Sauromatian and Sarmatian kurgans dating from the 6th to the 3rd centuries BC in

the Pokrovka region of the southern Ural steppes in Russia not far from Orenburg. Between the 4th and the 2nd century BC Sarmatian tribes from

the southern Urals moved southwards and westwards, some penetrating the lower Volga region others occupying the steppes north of the Black Sea.

Other groups pushed down into the Ustyurt and Aral region and may have been responsible for the conquest of Khorezm in the late 2nd century BC.

Herodotus recounted a myth about how the Sauromatians originated as the offspring of Scythian warriors who had mated with a band of Amazon women.

He went on to observe that: "Ever since then the women of the Sauromatae have kept their old ways, riding to the hunt on horseback sometimes with,

sometimes without, their men, taking part in war and wearing the same sort of clothes as men."

Yablonsky and Davis-Kimball identified that 35% of burials in this region related to high-status females. Many female graves contained imported

amber, coral, carnelian, turquoise, and glass beads and the remains of gold jewellery, demonstrating individual female wealth. Some 15% of the

females were classified as "warriors", having been buried with daggers, swords, arrow heads, quivers, and sometimes armour. Some 7% were

classified as "priestesses", being buried with mirrors and ceremonial vessels, and 3% as "warrior-priestesses". Of course the presence of

weapons in a grave does not necessarily imply a life of combat, although severe head injuries and a bronze arrow head embedded in a knee suggested

some women did engage in battle. One early Sarmatian priestess had gold feline attachments and gold temple pendants, while excavations in 2003

uncovered a 30-year-old warrior priestess with a large unoccupied space above her head that may have been a headdress. More female burials were

found at Filippovka 60 km west of Orenburg, one containing a mirror decorated on the back with females wearing elaborate headdresses with two

projections on the top.

The Sarmatians were also notable for their jewellery, made in the polychrome style, with objects of gold set with coloured stones such as garnets,

emeralds, amethysts, and agates and sometimes embellished with hanging pendants. This style may have been inherited from further west and was

particularly strong in the Pontic region. Diadems, temple pendants, necklaces, and earrings have been recovered from numerous high-status female

burials.

|

Polychrome jewellery was not confined to the west, as demonstrated by the 1939 find of 2nd or 1st century BC diadem fragments at the mountain

site of Kargaly, not far from Almaty. The original diadem had delicate gold lattice sides, incorporating figures of Siberian stags and phoenixes

set with precious stones.

It is likely that some of the nomadic cultures that succeeded the Sakas and Sarmatians, such as the Alans, maintained a similar material culture

into the first half of the 1st millennium AD and beyond. For example the Jety Asar nomads living in the delta of the Syr Darya were

descendants of the Apasiak Massagetae and their high-status women wore helmet-shaped headdresses covered with rows of small metal plates, just

like the Black Sea Scythians, while the Scythian animal-style of metalwork was maintained up to the 9th century in western Siberia.

|

|

However the westward migration of warlike Hunnic and Turkic nomadic groups was leading to massive cultural changes. Although we have some

information about the male costumes of these peoples, little is recorded about the fine details of feminine costume, making it virtually

impossible to accurately track the development of high-status headdresses through the first millennium. Marcellinus recorded that the Huns,

who overwhelmed the Alans in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, dressed in linen cloth or in "the skins of field mice sewn together", covering their

heads with round caps. They were polyandrous and one Chinese report claimed that their married women wore horns in their headdresses according

to the number of their husbands. Two headdresses were actually recovered from the much earlier Hsuing-nu site at Noin Ula close to Lake Baikal,

a circular embroidered cap quilted with felt with sable edgings and silk ear covers, and a tall plain helmet-shaped cap of silk made on a frame

of birch-bark with ribbons on either side for fastening under the chin.

We know a little bit more about the Hephthalite Huns. In 519 the Buddhist pilgrim Sun Yün travelled through their territories in Badakhstan

(southern Tajikistan and northern Afghanistan). He not only described their seasonal nomadic lifestyle and their felt tents but also an encounter

with their king and queen, the latter wearing a cornered turban eight Chinese feet in length and three Chinese feet in the diagonal, adorned with

"pearls in rose and five other colours on top". The wives of high officials also wore elaborate headdresses – called qu-qu or

ku-ku in Chinese. Sun Yün noted that "each seemed to wear a cornered turban that was round and trailing", presenting "the appearance

of a gem-decorated canopy of precious materials." These ku-ku became so popular in the Chinese court that their material composition and

size had to be regulated. For the Chinese they remained a passing fad, but for the nomadic tribes in the east their use seems to have persisted

because we see a similar type of headdress reappear under the same name at the time of the Mongols.

The first Turkic nomads began to infiltrate Central Asia from the mid-6th century onwards. Their aristocratic leaders extorted vast quantities

of gold, silk, and fine embroideries from the Chinese and we know from many sources, also mainly Chinese, that male court dress consisted of

sumptuous kaftans, long coats with bold decorated edges and a single lapel, belts covered with decorated metal plaques, the hair being worn long,

either loose or neatly plaited. The pilgrim Hsüan-tsang described the yabghu T'ung Shih-hu not far from Lake Issyk-kul in 630.

He wore a green satin robe, had free-flowing hair ten feet in length, and had a band of white silk wound around his brow, the ends hanging down

his back. Descriptions or images of aristocratic women however are rare. Frescoes at Qızıl show women in tightly fitting bodices

and voluminous skirts. The more eastern Uighurs are shown at a later date in frescoes at Murtuk-Bezeklik in Turfan. These show both men and

women wearing a tall mitre-like headdresses on the tops of their heads along with Chinese-style costumes. The women may have been Chinese wives -

their hair is uncovered and coiffured in the Chinese style.

One potentially rich source of information is provided by the wall paintings at Panjikent, Afrasiab, and Varakhsha. The Hephthalites took brief

control of Sogdiana around 509, but were defeated by an alliance of the Turks and Sasanians in 565. The Sogdians then came under Turkic rule

until the collapse of the first Turkic Qaganate in the mid-7th century. The 6th to 8th century murals contain illustrations of female costume

including various headdresses, some of soft felt and pointed, some helmet-shaped and diadem-covered, others low and cylindrical and covered with

polychrome silk. At the same time many women wear no head cover and expose their plaited hair. Unfortunately the aristocrats and merchants

depicted in these murals are not nomads. However Yatsenko believes that the Sogdians were more affected by Turkicization than any other Iranian-

speaking people and this is shown in their adoption of kaftans, sleeved coats with two lapels, and waist belts. For women it involved the plaiting

of the hair into braids and the wearing of hair braids.

The murals in the "Hall of the Ambassadors" at Afrasiab actually include images of male Turkic officials in long belted tunics with their hair

in long plaits. Interestingly Yatsenko believes it is likely that the Sogdians had already adopted Turkic marriage customs by the time these

murals were painted, around 650. He suggests that one of the murals at Afrasiab may represent a procession of aristocratic brides from neighbouring

states arriving for a politically important wedding aimed at linking their respective dynasties. However there are other scholarly interpretations

of this scene, such as a royal procession with the regent in a pallaquin mounted on the elephant and the secondary wives on horseback. Whatever

the correct interpretation, the images of the high-status women are generally missing, apart from one which includes no headdress.

Further west the people of the lower Volga region were also becoming Turkicized, with the powerful Khazar confederation emerging between the Don

and the Volga, and the Bulghars to their north. However the proto-Mordvin tribes of the middle Volga may have been more affected by immigration

from the Baltic. Archaeological excavations of cemeteries dating from the 5th to the 9th centuries have shown that proto-Mordvin women wore a

variety of jewellery including two types of headdress. The first consisted of several rows of bronze tubes or bronze spirals alternating with

rectangular or circular plaques, all attached to a leather or cloth backing. The second consisted of short strips of leather wound with bronze

wire, from which were suspended bottle, star, or bell-shaped pendants. Braid ornaments were constructed in a very similar manner. The pendants

became more elongated over time. The Mordvins seem to have increasingly influenced the material culture of the Bulghars and the Mari. Headdresses

composed of metal plaques and tubes begin to appear in proto-Mari graves between the 9th and the 11th centuries.

The ambassador Ahmed ibn Fadlan travelled from Baghdad to the Volga in 921/22 via Khorezm, progressively passing through the territories of the

Oghuz, Pechenegs, and Bashkirs before reaching the Volga Bulghars. His descriptive account reveals his contempt for many of the nomadic people

he encountered – the Oghuz with their stained unchanged clothing and coarse unveiled wives, the pagan louse-infested Bashkirs, and the dirty Rus.

He met the wives of several tribal leaders, yet made no mention of any distinctive headdresses. The wealthiest Bulgar women wore collars of golden

dinar coins, one collar apparently holding up to ten thousand dinars. A woman could wear several of these collars, depending on

the wealth of her husband. These wives also wore long necklaces of green glass beads, along with a circular "box" suspended below their breast

made of wood, iron, silver, or gold, depending on status. Ibn Fadlan also recorded that all the Bulghars wore the qalansuwa, an item of

head wear imported from Baghdad, shaped like a truncated cone and supported by an internal framework of reeds or wood. It was usually worn with a

turban wrapped around it. The finest examples in the Muslim world were encrusted with semi-precious stones.

Interestingly the Hudûd al-Âlam, written a little later in 982 and generally short on details of costume, does record that the Rus wore "woollen

bonnets with tails let down behind their necks."

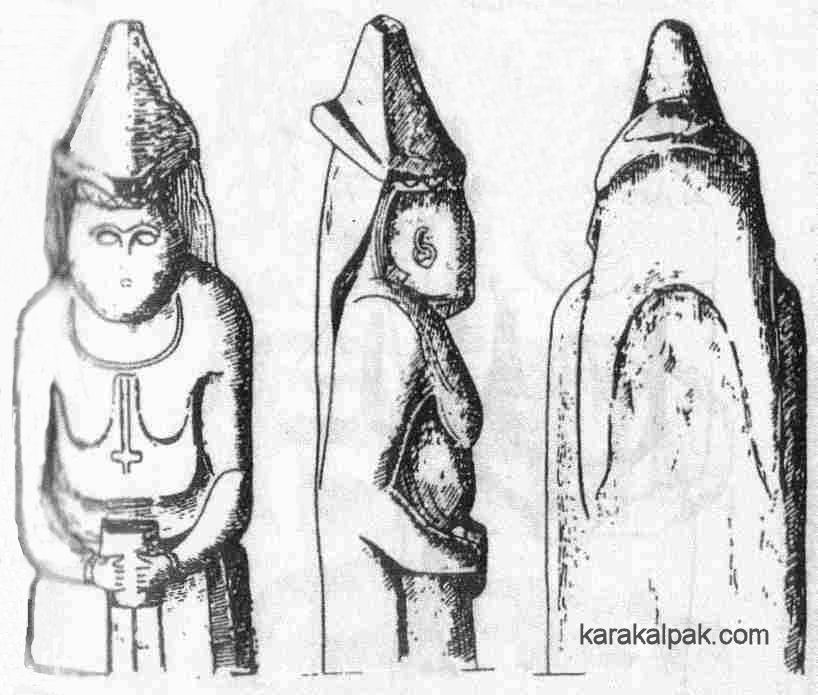

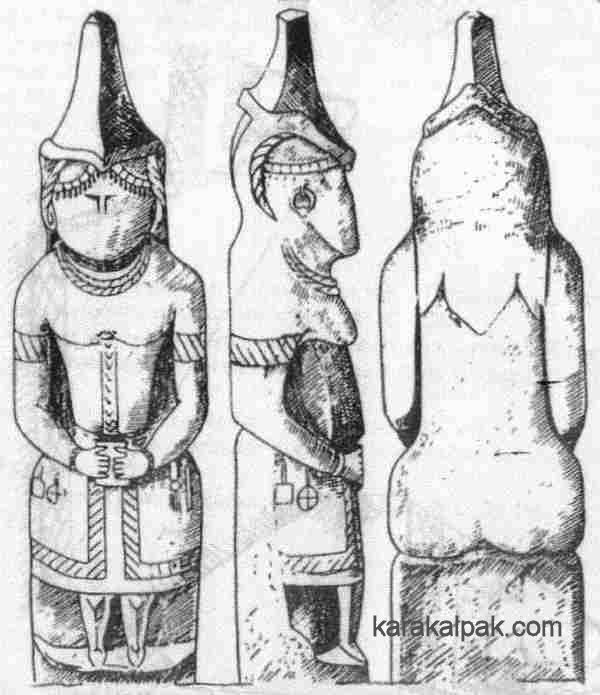

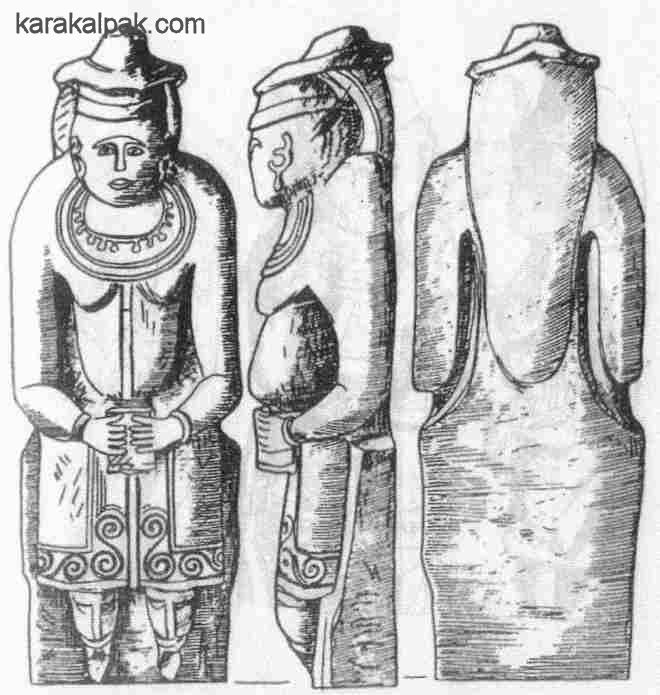

Our knowledge of the Pechenegs, who probably originated from the middle Syr Darya, is even scantier than that of the Turks. However we do gain

significant new insights into regional nomadic costume following the arrival of the Qipchaqs into the Aral area in the middle of the 11th century.

Those Qipchaq tribes who migrated into the Dnieper region of the Ukraine became known as Polovets and erected a multitude of finely carved rock

sculptures during the 12th and first half of the 13th century. Known as babas, they illustrate many details of male and female costume

and demonstrate that mature, presumably married, women wore a wide range of elaborate headdresses, some flat, some helmet-shaped, some conical,

and some tall. One of the tallest headdresses is worn by the so-called "Azov Princess", located in the Tanais Museum, near Azov. Many

headdresses incorporate forehead covers, some decorated with short hanging chains. Some headdresses are attached to drapes or plait covers

at the rear that completely cover the hair and hang down to the middle of the back or to the waist. Other headdresses reveal details of the

plaited hair. The headdresses are generally worn with elaborate jewellery including necklaces and earrings. In some cases the neck is

circled by a richly decorated upper breast cover, a cloak covering the top of the shoulders and falling down at the back.

|

|

|

The variety of styles is astounding and might relate to differences between tribes and, perhaps, changes over time. We shall encounter a

similar kaleidoscope of designs when we come to discuss the Tartar tribes inhabiting the central steppes during the 18th century. It is of

course not clear as to whether these costumes were introduced into western Eurasia by the Qipchaqs themselves or whether they were adopted

from the peoples of the Siberian, Aral, or Volga regions through which they passed. The only firm evidence supporting a Qipchaq origin comes

from the find of a ceremonial silver headdress in the Irtysh region that resembles the headdresses depicted on some Polovets rock statues.

Remarkably the remains of similar tall headdresses have been recovered from Qipchaq kurgan burials to the east of the Dneiper region. Ivanov

and Kriger have analysed 94 such burials across a territory ranging from the mouths of the Volga and Ural Rivers northwards into the southern

Ural Mountains. The kurgans date from the 12th to the early 15th century. This sample represents 34% of all known burials from this particular

territory and time period. In 10 of the 94 burials they identified the remains of cylindrical birch-bark tubes from tall female headdresses.

Such tubes were only found in burials containing a female skeleton and were generally accompanied by other female grave goods, such as mirrors and

earrings. Although a few beads were excavated from these burials it seems that necklaces were not a feature of female adornement in the Volga-Ural

region at this time.

|

The tubes were made from several layers of white birch-bark and were stitched along the side to form a cylinder or cone. They were sometimes

found with remains of their original cloth covering or with appliquéd silver plates. The headdresses fell into two categories according to

their length: they were either 10 to 15cm long, or 25 to 35cm long. The diameter of the tubes ranged from 3 to 8cm, one end sometimes being wider

than the other.

Ivanov and Kriger concluded that such headdresses preceeded the arrival of the Mongols and may have been derived from the traditional headgear of

the original Qimek-Qipchaq federation. During the Golden Horde era their use seems to have become widened well beyond the elite tribal aristocracy.

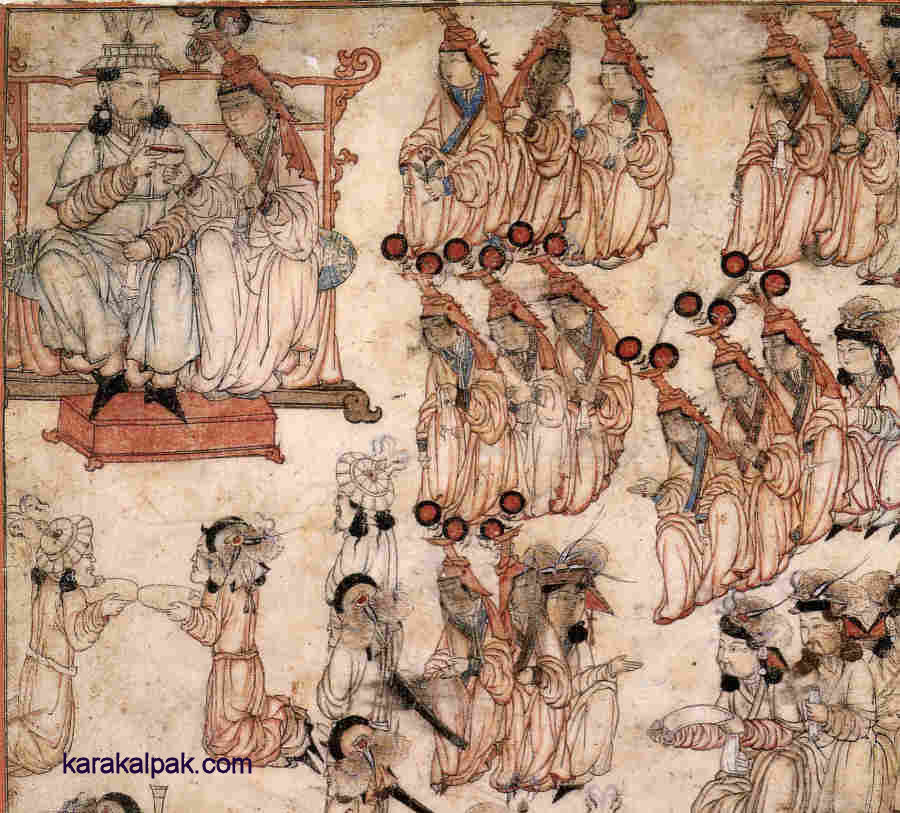

The first historical reference to the use of the tall headdress by the Mongols occurs in "The Secret History of the Mongols", penned by a member of

the Borjigins, the clan of Chinggis Khan, in the early 13th century - possibly 1228. It concerns Chinggis Khan's mother at the time she was abandoned

by the Tayichi'uts and the rest of the Borjigins following the assasination of her husband by the Tatars, an event that occurred just after 1170:

"Lady Hö'elün, born a woman of wisdom,In 1221 Chinggis Khan's Mongol armies conquered Khorezm and its army of Qipchaq mercenaries. At the same moment, the elderly Taoist monk K'iu Ch'ang Ch'un was on his way from China to Samarkand to visit the Great Khan, accompanied by Li Chih-chang and 18 other disciples. After following the Kerulan River towards the Mongolian Altai they encountered a large number of Mongolian nomads living in black carts and white gers:

raised her little ones, her own children.

Wearing her high hat tightly [on her head],

hoisting her skirts with a sash,

she ran upstream along the Onon's banks,..."

"The men and unmarried girls plait their hair so that it hangs down over their ears. The married women put on their heads a thing made of the bark of trees, two feet high, which they sometimes cover with woollen cloth, or, as the rich used to do, with red silk stuff. This cap is provided with a long tail, which they call a yu-yu, and which resembles a goose or duck. They are always in fear that somebody might inadvertently run against this cap. Therefore, when entering a tent, they are accustomed to go backward, inclining their heads."From the numerous Eastern and Western travellers who visited Mongolia and the Qipchaq Steppes in the 13th century we can see how this headdress was transformed into the boghtaq or bughtaq, the most visible symbol of status for aristocratic married Mongol women, local native materials being quickly superseded by more exotic fabrics and jewels from China and Islamic Central Asia.

|

In 1237 another Sung envoy, Hsü T'ing, personally witnessed the construction of Mongol ku-kus and observed that their frames were

now wrapped "with red silk or with gold brocade".

|

By now Batu and several of Chinggis's other grandsons were expanding westward, conquering the Qipchaq steppes as far as Moscow, including the

territories of the Volga Bulghars and the Mordvins. Batu eventually located the mobile capital of his Qipchaq or Golden Horde at Saray on the

Volga.

In 1245 and 1246 the Italian Franciscan Giovanni del Pian di Carpini, the ambassador of Pope Innocent IV, travelled from Lyon to Saray, located

on the Volga, and onward to Qaraqorum. He recorded details of the the costume, dwellings, and customs of the Mongol aristocracy:

"The married women have a very full tunic, open to the ground in front. On their head they have a round thing made of twigs or bark, which is an ell in height and ends on top in a square; it gradually increases in circumference from the bottom to the top, and on the top there is a long and slender cane of gold or silver or wood, or even a feather, and it is sewn on to a cap which reaches to the shoulders. The cap as well as this object is covered with buckram, velvet, or brocade, and without this headgear they never go into the presence of men and by it they are distinguished from other women."Friar William of Rubruck followed a similar route to Carpini in 1253 to 1255 and left us a more detailed description of the same headdresses. The wives of the Mongol leaders were apparently very fat, smeared their faces with paint, and had the front half of their heads shaved:

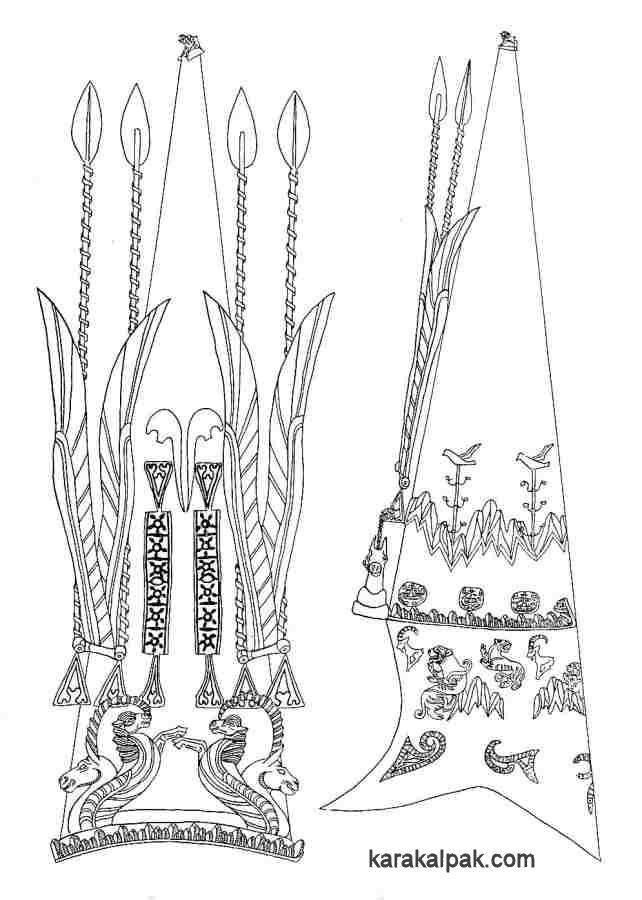

"In addition they have a head-dress called a bocca and made of tree bark or some lighter material if they can find it. It is thick and round two hands in circumference and one cubit or more high, and square at the top like the capital of a column. They cover this bocca with expensive silk cloth: it is hollow inside, and on the capital in the middle, or on the square part, they put a sheaf of quills or of thin reeds, again a cubit or more in length. And they decorate this sheaf at the top with peacock's feathers and around its shaft with the little feathers from a mallard's tail and even precious stones. This decoration is worn on the top of the head by rich ladies: they fasten it on securely with a fur hood which has a hole at the top made for this purpose, and in it they put their hair, gathering it from the back onto the top of the head in a kind of knot, and placing over it the bocca, which is then tied firmly at the throat. Consequently when a number of ladies are out riding and are seen from a distance, they resemble knights with helmets on their heads, and raised lances: for this bocca looks like a helmet and the sheaf [protruding] above like a lance."Rubruck actually observed one Mongol woman removing her bocca during a Nestorian ceremony, revealing her completely shaved head.

|

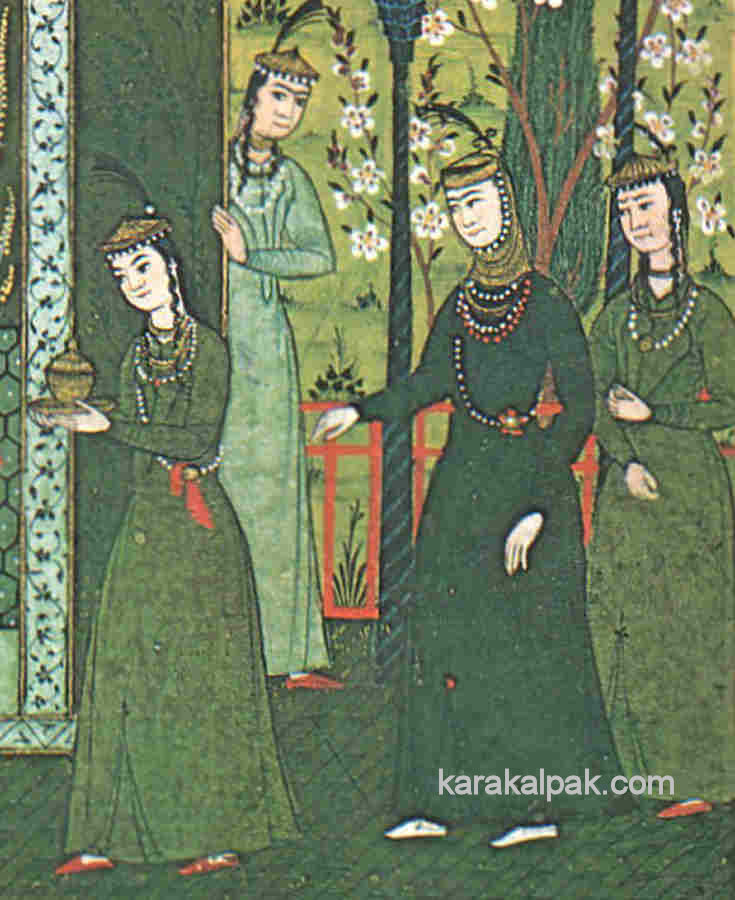

The boghtaq had become a symbol of the high status of Mongol noblewomen and, by around 1270, its use became proscribed by the Mongol court.

Headddresses became more and more elaborate, embellished with jewellery and gold plaques. The rapid growth in long distance trade throughout the

Mongol Empire was increasing the availability of exotic jewels among the Mongol aristocracy. Rubruck observed that their textiles were imported

from many regions: China, Persia, Russia, Bulgaria, and Hungary. The merchants Nicolo and Maffeo Polo profited greatly after acquiring fine jewels

in Constantinople and selling them to Berke Khan on the Volga.

Archaeological materials suggest the boghtaq was worn by city dwellers as well as nomads during the Golden Horde period. A fine example

was recovered from a wealthy woman's burial in a 13th century mausoleum at the medieval city of Ukek, on the Volga. It was a cap of red silk with

wing-like projections on its sides, fastened at the back with ribbons tied in bows. A hollow cylinder covered with silk and silver plaques rose up

from the cap with a gilded wooden board attached to its top, covered with silk and decorations made from silver wire. Following the Mongol conquest

of China, the boghtaq also became the standard headdress for aristocratic married women in China throughout the period of the Yüan

dynasty (1280-1368):

|

The boghtaq also influenced the costume of the southern Rus, where wealthy married women wore a kiki. This was a similar tall and

rigid headdress, worn above a softer cap, covered with satin or silk and decorated at the front with pearls and jewels, a rear velvet or sable flap

covering the nape of the neck.

The headdress of the female Mongol aristocracy must have also deeply impressed the leadership of the nomadic Tartar tribes living in the territories

of the Golden Horde and beyond. The boghtaq or ku-ku was soon adopted by their own wives.

Ibn Battuta traversed the Qipchaq Steppes in 1334 and made notes on the head wear of various high-status Turkic women:

"As for the wives of the traders and commonality, I have seen them, when one of them would be in a wagon, being drawn by horses, and in attendance of her three or four girls to carry her train, wearing on her head a boghtaq, a conical headdress decorated with precious stones and surmounted by peacock feathers. The windows of the tent would be open and her face would be visible, for the women folk of the Turks do not veil themselves. One such woman will come [to the bazaar] in this style, accompanied by her male slaves..."While at the camp of Özbeg Khan at Beshdagh he described the ceremonial dress of one of his wives, or Khatuns, as she travelled in her caravan of over four hundred wagons:

"On the khatun's head is a boghtaq which resembles a small "crown" decorated with jewels and surmounted by peacock feathers. And she wears robes of silk encrusted with jewels, like the mantles worn by the Greeks. On the head of the lady vizier and the lady chamberlain is a silk veil embroidered with gold and jewels at the edges, and on the head of each [slave] girl is a kulāh [cap], which is like an aqrūf [fez] with a circlet of gold encrusted with jewels round the upper end, and peacock feathers above this, and each one wears a robe of silk gilt..."We know that at least one boghtaq was brought back to Europe by Marco Polo at the end of the 13th century. It is possible that these headdresses may have been responsible for the sudden popularity of conical hats and headwear across northern Europe in the 15th century, including the conical headdress and veil known as the hennin, which was introduced by Isabeau de Bavière and was worn with the hairline plucked so that no hair was revealed. The hennin has since become the headdress of the Western fairytale princess.

"The Great Khanum wore before her face a thin white veil, and the rest of her headdress was very like the crest of a helmet, such as we men wear in jousting in the tilt yard: but this crest of hers was of red stuff and its border hung down in part over her shoulders. In the back part this crest was very lofty and it was ornamented with many great round pearls all of good orient, also with precious stones such as balas rubies and turquoises, the same very finely set. The hem of this head covering showed gold thread embroidery, and set around it she wore a very beautiful garland of pure gold ornamented with great pearls and gems. Further the summit of this crest just described was erected upon a framework which displayed three large balas rubies each about two fingers breadths across, and these were clear in colour and glittered in the light, while over all rose a long white plume to the height of an ell, the feathers thereof hanging down so that some almost hid the face coming to below the eyes. This plume was braced together by gold wire, while at the summit appeared a white knot of feathers garnished with pearls and precious stones. As she came forward this mighty head-gear waved backwards and forwards, and the Princess was wearing her hair all loose, hanging down over her shoulders. ... To keep the crest and other adornments steady on her head the Princess was attended by many dames who walked beside her, some of whom while supporting her kept their hands up to the headdress; indeed in all she appeared to have around her as many as three hundred attendants."The Great Khanum was followed by eight more Princesses all similarly robed and bejewelled. This fashion was clearly of Mongol origin - when Ch'ang Ch'un was in Samarkand in 1222 he noted that the wives of chieftains or the wealthy wore a black or dark red turban sometimes embroidered with flowers and other motifs.

|

However the archaeological evidence shows that such boghtaq headdresses were still in fashion in the Volga-Ural region in the early part

of the 15th century.

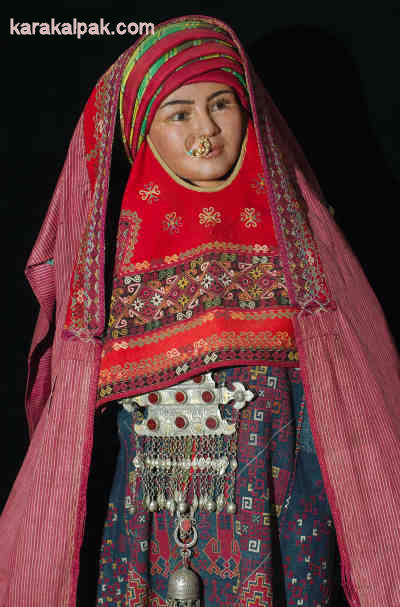

From the 17th century onwards the Eurasian steppes and Siberia were increasingly penetrated by European and Russian travellers and many have left

us comments on the people they encountered. Together these reports give us our first comprehensive, historically documented record of Central

Eurasian nomadic costumes. They show that despite the many differences that distinguished the individual Tartar tribes, their costumes incorporated

many common features across a huge geographical area. One of these was the adornment of married women with dramatic headdresses, which tended to

be tall and pointed or helmet-shaped. They often incorporated decorated forehead and ear covers and usually had some type of long plait cover at

the back. They were elaborately embellished with coral, pearls, glass beads, metal plates, and coins and were often worn with necklaces, ear- and

nose-rings.

Anthony Jenkinson had passed through the territories of the Mordvins, the Kazan Tartars, the Cheremiss, the Noghay, and the Crimean Tartars in 1558

but left us no descriptions. The Russians had just annexed the region and the local tribes were putting up strong resistance. Over the next 20

years the Cheremiss Wars would result in the death of about half of the Mari population. Consequently Jenkinson sailed down the Volga with

little chance of visiting local Tartar villages. Eighty years later the Volga region was still dangerous for travellers but the German scholar

Adam Olearius, accompanying a diplomatic mission from Holstein to Isfahan via Astrakhan in 1638, did get the opportunity to visit a few local tribes.

Some 120 versts south of Nizhniy Novgorod he visited the Cheremiss [Mari], who engaged in polygamous marriage. Despite their semi-pagan

beliefs the women were veiled and brides wore "an ornament almost like a horn, forward on their heads; it extends upwards an ell in length, and at

its tip, in a coloured tassel, hangs a little bell". Further south in Astrakhan the Noghay and the Crimean Tartar women wore white linen cloaks

and round, pleated hats, which extended to a point and were not unlike helmets. "In front, these hats are hung with Russian kopecks joined in

rings." Olearius later recorded that in Persia women were wearing headdresses in the Tartar style, with two or three rows of pearls across their

foreheads, falling down across their cheeks and fastened under the chin so that their faces seemed to be set in pearls. He also reported the head

wear of Russian brides: a crown made of finely beaten gold or silver plate and lined with cloth, curved near the ears, and with suspensions of 4,

6, or more strands of large pearls falling well below the breast.

In the summer of 1703 Corneille Le Bruyn visited the Tartars encamped just outside of Astrakhan and was delighted to see a woman wearing a

headdress made of silver or copper gilt, covered with golden ducats, pearls and precious stones.

In 1733 Johann Gmelins and the Prussian Gerard-Frederic Muller left Saint Petersburg on a ten year expedition, travelling via Kazan and the middle

Volga into southern Siberia and west towards the Pacific. In the first part of their journey across the Qazaq Steppes they encountered various

Tartar tribes in which married women wore elaborate headdresses, both helmet-shaped and conical, always decorated with coral beads and kopeck coins,

often embellished with rear plait covers made from ribbons. They found specific examples in Katschielina, east of Kazan, Sirijes, Werchoi-Pobja,

Kungur, and Jalum.

|

|

Aware of growing developments in western science, the German-born Empress of Russia, Catherine II, encouraged many European academics to Saint

Petersburg. In 1767 she attracted Peter Pallas, a Berlin Professor of Natural History, to join the Academy of Sciences, just in time for him to

join an important astronomical expedition planned for the following year. His team travelled through eastern Russia and Siberia for five years,

documenting the peoples and natural history of these regions for the very first time. While Pallas concentrated on Siberia, the Swedish

botanist Johann Falk, assisted by Johan Georgi and Christoph Bardanes, visited the Pontic, Qazaq, and Hungarian Steppes. Johann Georgi extended

the expedition from the Urals to the Altai, Lake Baikal, and Mongolia. Meanwhile Johann Güldenstädt visited the Caucasus in 1768-69.

A little later, in 1793-94, Peter Pallas also visited the Caucasus as well as the Black Sea steppes and the Crimea.

They concluded that Tartar men invested substantially in the costumes of their wives (or the eldest wife if they had several) as a means of

enhancing their own status – the dress of some women could be worth around 500 roubles, an enormous sum of money at that time. They also

recognized common features in the many different costumes they encountered, particularly headdresses that concealed the forehead and ears,

had long rear plait covers, and were encrusted with corals, pearls, beads, medallions, and coins.

Their descriptions of married women's headdresses for the different ethnic groups can be summarized as follows:

Kazan Tartars wore a breast cover called a kashpaou kairyuok covered in a scale-like fashion with medallions and beads. They wore

a cord-like ribbon at the back of the shoulders covered with glass beads and gold or silver medallions, along with necklaces and ear rings.

Orenburg Tartars wore a bonnet called a tchasbau covered with rows of coins and medallions, giving the appearance of scales, and having

large flaps that partially cover the ears. At the back was a 3 inch wide plait cover called a kashpur which reached down to the calves.

Underneath the hair was tied in two thick braids. Over their face they wore a net of fine pearls. For special occasions this was surmounted by

an additional flat headdress, its edges trimmed with pearls.

Astrakhan Tartars wore flattened caps trimmed with marten fur and covered their face with a veil.

Noghay Tartars sometimes wore fur caps edged with cloth and had a decorative band hanging from the back covered with glass beads, like the Kazan

Tartars and the Cheramiss. Edmund Spencer described the festival dress of young Noghay Tatar women in 1839 as consisting of a high round cap of red

cloth, ornamented with gold Turkish coins. In addition they wore a band of coral and small shining shells over the forehead. Their hair hung down the

back in a long thick plait tied with a silver cord.

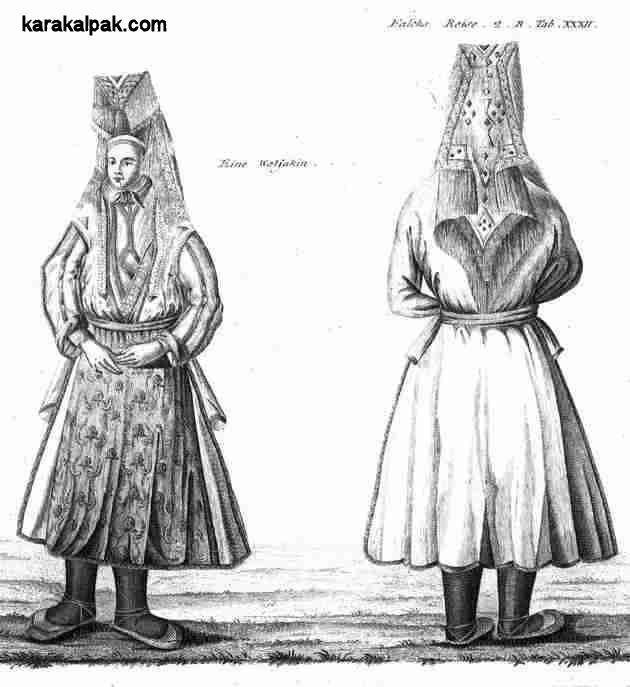

Qazaqs wore a skullcap called a takia, which was quilted and pointed. On top of this they wore a conical headdress, edged with fur

like the Kyrgyz equivalent. It had flaps on each side that covered the cheeks but which could also be folded up in the air like a basket. The

top of the cone was decorated with a gather of cloth. In addition they wore necklaces decorated with tassels, ribbons, and jingling metal

platelets. Falk and Bardanes visited Sultan Mamet of the Qazaq Middle Horde in 1771 and observed his rather substantial wife wearing a silk

cloth around her head and a headband decorated with strings of corals that hung over her cheeks. Falk's travel diary, which was published some years

after his death, described and illustrated a different type of Qazaq headdress that was worn by wealthy women and was very similar to that being worn

by the Volga Tartars. It included a breast cover decorated with rows of corals and silver and gold coins, a high cap and a long and wide plait cover:

|

|

Bashkirs in the region of Ufa wore a breast cover known as a dulbega covered with medallions like scales or with nettings of shells

and beads. On their head they wore a cap decorated with rows of coral and short hanging chains of silver and coins, which covered the ears, cheeks,

and forehead. The cap had a plait cover at the back, known as a tastar, which covered the nape and dropped down to the calves and was

decorated with medallions and beads. They also wore a headband over the cap, decorated in the same fashion.

|

Chuvashes wore a helmet-shaped headdress decorated with horizontal rows of beads and metal plates, topped with a gather of cloth. Ear covers on

each side hung down to the shoulders, while an embroidered plait cover hung down the back to the rear of the knees.

|

Mari or Cheremiss wore a tall conical headdress with a truncated top, decorated with horizontal rows of platelets. Their ears and hair were covered

by a cloth that tied under the chin. There was a long plait cover at the back that covered the nape and fell down to the ankles and was decorated

with hanging platelets and medallions.

Mordvins wore a helmet-shaped headdress with a flattened back, richly decorated with beads and rows of hanging chains. Strings of beads hung down

from each side covering their ears, while at the back there was a short but wide plait cover that reached down to the shoulder blades, also richly

decorated with embroidery, beads, and short hanging chains.

|

Udmurts (referred to as Wotjaks) from the Kama region of the upper Volga, wore a high headdress with a vertical top, draped with an embroidered

and fringed shawl that decorated the front of the headdress and then hung in pleats behind the head down to the shoulders, covering the hair. It

had lengths of cloth fastened at each side that covered the ears and were fastened together below the chin.

|

Pallas was particularly impressed with the latter Wotjak headdress:

"The headdress of their women belongs to the most extraordinary and enormous headdresses in use among the many peoples under the sway of Russia. A piece of birch bark, one span high, is bent into half a cylinder which fits onto the head, connected behind by a narrow strip of bark, and on the inside fastened with a wooden bow and kept apart by a small cross-piece of wood. Another double quadrangular piece of birch-bark almost one span high, similarly fastened with a cross-rod at the back, is stitched on above the top edge and fastened in a way in which it bends slightly forward with both sides bending backwards. This upper piece of bark is normally covered in a piece of red fabric while the lower part is covered in blue, the latter being covered on the outside with kopecks or tin plates. This two-span tall fontange is fastened to the head with a strap fixed to the rear part and is worn tilted slightly forward like an infantry cap. This framework is given a most distinguished look by being worn together with a square kerchief which is stitched along the edges and at the corners with red, blue, and brown thread, and a centre decorated with diamond-shaped inserts, surrounded by finger-long frays of blue, red, and white threads. The same piece of cloth is fixed to the upper edge of the bark pieces so that one corner hangs down at the front thus concealing the upper piece of bark, revealing only the piece which is adorned with silver or tin-plate, two corners embellish the sides of the frame and the head, right down to the shoulders, and the fourth corner falls down the back. Underneath this headdress the women plait all their hair at each side of the head over the ears where it is tied in a thick knot which by some is decorated with corals or rattles. No married woman would expose herself without wearing this headdress and even when newcomers arrive late at night in Wotjak houses, they will observe the women go to sleep wearing the headdresses, which, by the way, are never displaced or fall from their position when the women are in motion or working. Only widows and quite old women alleviate themselves from this burden by simply tying a triangular kerchief around their heads, one embroidered corner of which falls down their backs.Although Pallas, Falk, and Georgi made some brief secondhand comments about the Karakalpaks, they did not visit the Aral region and so could not describe the local costume.

|

|

Pauli published a coloured lithograph of a Qazaq saw'kele in 1862, while another from the Greater Horde was printed two years later:

|

|

|

In 1868 Vambery noted that Qazaq women wore a sheokele, which was more conical than the Turkmen headdress and "allows the veil to

fall not before, but down the back of the loins." They braided their hair into eight thin plaits, four on each side, and covered their heads

with a letshek in cloth, which covered the head and neck.

When Henry Lansdell was in Vierny (today's Almaty) in 1874 he also commented on the headwear of the local Qazaq women:

"The poor women swathe their heads with calico, forming a compound turban and bib; but the rich wear a square headdress of huge proportions, enveloped in a white veil trimmed with gold. The hair is plaited in small braids, and adorned with coins and tinkling ornaments. To these may be added necklaces, bracelets, etc.; ..."He also commented on the Qazaq wedding ceremony, noting that on the completion of the wedding ceremony, the headdress of the bride was removed and replaced with that of a woman.

|

A little later, in 1883, Henrich Moser stayed with the Qazaqs of the Lesser Horde on the Orenburg steppes. He saw that among the ordinary nomads

the girls wore their hair uncovered, woven into plaits, while the married women wound a long white turban around the head, the bottom of the face,

and often the bust. However the wives of the local tribal leader, Suliman Sultan, wore sa'wkele headdresses. His favourite wife had a

cylindrical headdress of red velvet covered with precious stones, its lowest edge fringed with sable, its top decorated with a brush of heron and

ostrich feathers. A pointed flap terminating with a large turquoise stone covered her left ear. From the top of the headdress, veils of muslin

edged with golden fringes fell down onto her shoulders, while from the back of the headdress a cloak of white satin decorated with broad golden

stripes and solid gold fringes draped down to knee-height.

|

Qazaq sa'wkele were shown at the Lower Urban Exhibition of 1893, the most valuable being from the Atbasar steppe. A wider collection

from Akmolinsk, Kokcheav, Atbasar and northern Kazakhstan were shown at the Exhibition of the Third Congress of Orientalists in Saint Petersburg

in 1896. The embroidered sa'wkele presented by S. Chapenov was decorated with 30 strings of corals, 15 strings of pearls, and was covered

in gold and silver settings of semi-precious stones. It was valued at 600 roubles. Another (439-21) from Aktubinsk or possibly Kustanay was

donated to the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in Saint Petersburg by Birkambaev and Imambaev in 1899. At that time the cost of a

sa'wkele peaked at around 1,000 roubles, enough to buy 100 top horses. Other reports refer to valuations of from one to two million

silver coins, or up to one hundred camels.

|

One of the later descriptions of the Qazaq sa'wkele was reported by a French Vice-Admiral, Jules-Marie de Cavelier de Cuverville, in 1896:

"It consists of a one metre high cone covered in silver pieces, silver plate, precious stones, strange material and long bands of coral, a metre in length, decorated in ancient silver."He observed that although the headdress was becoming rare, it was still being used for some weddings. It was placed on the bride's head before she set off from her parent's aul to travel to the aul of the groom.

|

The sa'wkele was finally overtaken by changing fashions. For everyday wear the bas oramal head turban became universally

popular, tied in different styles depending on the locality. This was covered with a jegde when going outside of the home.

|

For weddings the brightly coloured qızıl kiymeshek was becoming increasingly popular, topped with a red tu'rme

or a checked oramal and covered with a jipek jegde. The finest wedding costume no longer depended entirely on the wealth of

the bride's father, but increasingly on the embroidery skills of the bride.

Conclusions

The Karakalpak sa'wkele seems to have little connection with the culture of the Saka-Massagetae. There might, however, be a long-term

connection between the tall conical Saka and Sarmatian headdress of central and northern Eurasia and the ancient tradition of shamanism, more

recently illustrated by the tall pointed caps worn by Central Asian dervishes.

Clearly some Saka, Scythian, and Sarmatian aristocratic women and important shaman priestesses wore tall conical headdresses built on a wooden or

birch-bark framework, a tradition probably inherited from earlier Bronze Age inhabitants of the forests and steppes. Such headdresses occurred

in different styles in different regions, but were not universal – high-status females wore a range of headdresses, not all of which were tall

or conical. As far as we can determine, no tall or conical headdress has yet been found in any Massagetae grave.

Although the tradition of the tall cone-like headdress seems to have been maintained throughout the first millennium among some of the nomadic

tribes in eastern Eurasia, there is no evidence of its continuation in the western regions.

Archaeological studies show that during the first millennium helmet-shaped headdresses were worn by the Jety Asar, descendants of the Aral

Apasiaks, some of whom later migrated into the Aral Delta. Further west some of the tribes of Finnish origin – the Mordvins and the Mari –

were developing headdresses based on rows of plaques and bronze decorations. Meanwhile the Hudûd al-Âlam refers to the early Rus

fashion of wearing caps with tails hanging down from the back.

At the same time the nomads of western Asia were gradually becoming Turkicized. Yet there is nothing to link the early Turks with any form

of distinctive headwear and although they plaited their hair, so did the earlier Sarmatians. Likewise when ibn Fadlan passed through the

territories of the Oghuz, Pechenegs, Bashkirs, and Bulghars he made no mention of female headwear, but did observe that wealthy Bulghar women

wore one or more collars of golden dinar coins.

The migration of the Qipchaqs into western Central Asia in the mid-11th century had a major impact on its already established nomadic peoples.

Many of the Oghuz and Pechenegs were forced to relocate and those that remained had all adopted the tribal identification of Qipchaq within a

century. Many common features of Karakalpak, Qazaq, Kyrgyz, and Uzbek yurt construction and decoration can be traced back to their common

Qipchaq origins, so it is possible that some features of their costume may also have similar roots. The Qipchaqs who settled in the Ukraine

left us evidence of a rich costume culture in which married women covered their heads and hair with a wide variety of elaborate headdresses

and plait covers. The key question is whether this culture originated from the Qipchaqs themselves or from the tribes they encountered and

overwhelmed during their westward migration?

The sparsity of historical descriptions of nomadic female costume prior to the Mongol invasion of Central Asia poses a major limitation on our

study. Although not conclusive there is some evidence suggesting that the Qipchaqs may have reintroduced the tall headdress to western Asia.

The wide variety of headdresses and costumes found among the Polovets of the Ukraine may have a Qipchaq origin or could be the expression of

a rich localized culture. It might also be the result of a merger between the cultures of the Qipchaqs and those of the Volga-Ural region.

Whatever their origin it is clear that high-status headdresses, decorated collars, and plait covers all existed in all or some of the regions to

the north of the Black and Caspian Seas prior to the Mongol invasion.

Clearly Chinggis Khan's decision to conquer Khorezm, followed by Batu's invasion of the Qipchaq Steppe, led to dramatic social and cultural changes.

Mongol rule reintroduced the boghtaq or ku-ku into Central Asia and the Volga, a highly visible symbol of aristocratic wealth

and power that was soon adopted as the headwear of the wives of the local Tartar leaders. In time elements of this fashion may have spread beyond

the tribal aristocracy to the nomadic middle classes, who already possessed their own form of the Mongol boghtaq. Was it the influence of

the Mongols that led to the increasing embellishement of nomadic costumes?

Each ethnic group seems to have evolved its own particular style of headdress, possibly influenced by local circumstances, some being tall and

conical, others helmet-shaped. The collapse of the Golden Horde in the early 15th century led to many tribal realignments and the emergence of

the Uzbek and Noghay Hordes and later the Qazaq Horde and the Karakalpaks. It is impossible to track the influences of individual tribal

groups on the fashions eventually adopted by each confederation. All we can say is that the same themes occur over and over again in the designs

of the headdresses used by the majority of tribes whose origins can be traced back to the Golden Horde and the Qipchaq Steppe region, ranging from

the Caucasus to western Siberia and from the Black Sea to the Altai.

The net result seems to be a cocktail of elements, some introduced from the east, others endemic to the west. Clearly the conical shape of the

Mari, Qazaq, and Kyrgyz headdresses with their associated ear covers seem to derive from the Qipchaq and Mongol boghtaq. On the other

hand the horizontal arrangement of beads and pendants seen in so many of these headdresses may go back to the jewellery styles of the early Mordvins

on the Volga, while the tradition of richly embellished collars and breast covers can be directly linked to the Bulghars. Indeed it is possible

that elements of this fashion may have found their way back to Mongolia, since many of the Mongol headdresses dating from the late 19th and early

20th century contain features that were common in 18th century Tartar headdresses.

The other widespread common feature relates to the headwear of unmarried girls and the tradition of plaiting the hair and decorating the plaits

with ribbons and coins, a tradition that might date back to the early Turks. It is possible that the Karakalpak to'belik or kasava

was once a maiden's headdress, just like the Qazaq kasaba or the Uzbek or Turkmen takiya. In some Karakalpak regions its use

seems to have been extended into the wedding ceremony, at some stage during which the bride's sa'wkele was crowned with the to'belik.

At the end of the day it is not surprising that the Karakalpak sa'wkele looks a bit of a mishmash. Not only was it formed through an

intermarriage of Qipchaq, Mongol, western Tartar, and Finno-Ugric costume cultures, but it was subsequently embellished by the Karakalpaks themselves

with the incorporation of red and black ushıga, the Khorezmian jıg'a, and the two-part halaqa.

In the end the growing extravagance of the sa'wkele led to its demise. It became increasingly unaffordable until only the wealthiest

Karakalpak bays could maintain the tradition. The increasing availability of English and later Russian broadcloth throughout the 19th century

created a new fashion - the qızıl kiymeshek, which increasingly became the preferred wedding costume of the Karakalpak bride

from the end of the 19th century until the 1930s.

Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms

To listen to a Karakalpak pronounce any of the following words just click on the one you wish to hear. Please note that the dotless letter

'i' (ı) is pronounced 'uh'.

| awıl | murındıq ene | Qırq Qız | tamg'a |

| boydası | omırtqa | qızıl kiymeshek | to'belik |

| bo'z | qara ushıga | qızıl ushıga | tumaq |

| halaqa | qıran | sa'wkele | tu'rme |

| jıg'a | qırg'ıy | segiz mu'yiz | u'yleniw toy |

| ko'k ko'ylek |

|

This page was first published on 12 September 2006. It was last updated on 25 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |