The Ko'k Ko'ylek

|

The Ko'k Ko'ylek

|

|

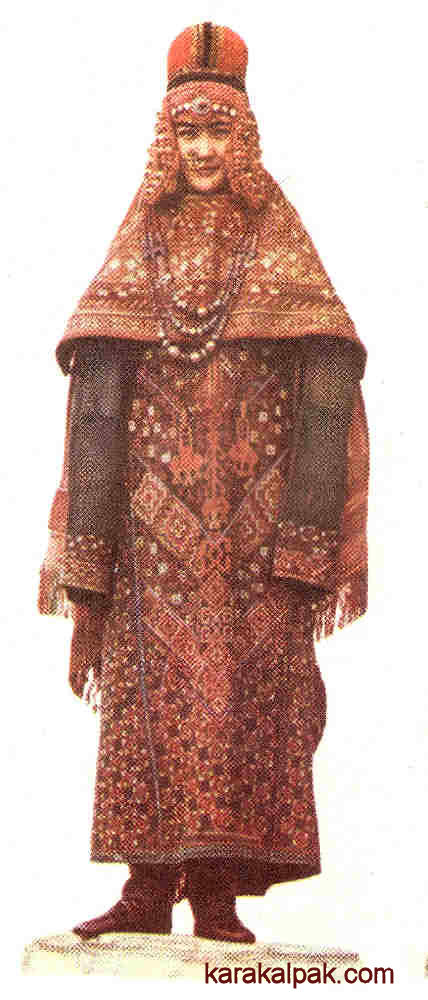

ContentsThe Ko'k Ko'ylekUsage Terminology Folk Beliefs Museum Collections History Links with the Volga and the Ob Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms References The Ko'k Ko'ylekThe Karakalpak ko'k ko'ylek was an ankle-length, long-sleeved, unlined woman's tunic-style dress. The entire front of the dress was intensively decorated with geometric cross-stitch embroidery, as was the bottom part of the sleeves. The back remained undecorated.The dress was hand-tailored from narrow strips of indigo-dyed homewoven cotton bo'z, called by the Uzbeks matar. These were sewn together side by side to make the body of the dress and the sleeves. The body had a single central front panel and no shoulder seams. The collar was round and had a narrow and deep vertical opening at the front, a style normally reserved for women of childbearing age to facilitate breast-feeding. There were lower side vents for ease of movement and sometimes a pocket. In some cases the edges of the collar, lower hem, side vents, and cuffs were finished with a narrow strip of red textile.

Traditional Karakalpak ko'k ko'ylek

|

|

These motifs are located below the breast, just at the point where the silver ha'ykel chest decoration is meant to hang. Meanwhile the

lower sections of the two front side panels are covered with a lattice of more segiz mu'yiz and sometimes other motifs. In some examples

these are linked by grid-like lines, in others they are arranged more randomly.

|

The decoration around the collar opening and the sleeve cuffs tends to be more variable, although the most frequently occurring pattern consists

of narrow diagonally oriented rows of small triangular teeth or zigzags with protruding rectangular hooks or horns and interlocking diamonds, some

containing rectangular scrolled horn motifs.

|

The outside joins between the panels of blue bo'z on the body of the dress were usually overembroidered with a line of

omırtqa or vertebrae motif.

Some ko'k ko'yleks were made with a narrow edging of red and sometimes black ushıga around the collar and cuffs, often

decorated in chain-stitch embroidery using the same combination of red, yellow, and white silk threads. These features probably date from the

late 19th or the early 20th century, following the growing fashion of embroidering in chain-stitch on commercial ushıga broadcloth.

Usage

Ko'k ko'yleks are mainly associated with the northern Karakalpak Qon'ırat arıs. Although we lack the complete

provenance of the ko'k ko'yleks in current museum collections, we do know that they were mainly acquired from locations in the northern

delta such as Qarao'zek, Taxta Ko'pir, Shege, and Qon'ırat. Ag'ınbay Allamuratov discovered that a considerable number of ko'k

ko'yleks had been made in the village of Aq Darya in Moynaq region, and while one or two have been acquired by museums, the majority have been

lost. Allamuratov also found that some ko'k ko'yleks had been made by the On To'rt Urıw living in the Kegeyli and Shımbay

regions, since local people retained a folk memory of the dress and its sawıt nag'ıs decoration.

The ko'k ko'ylek primarily functioned as a high-status bridal gown, used for the marriage of girls belonging to wealthy Karakalpak families.

They were traditionally handed down from mother to daughter. Some wealthy families even commissioned the best embroiderers in their region to make

a ko'k ko'ylek for the wedding and some embroiderers gained income and fame for this work. Some elderly Karakalpaks have told us that within

some communities in the past, a ko'k ko'ylek could be borrowed or hired for a specific wedding. One very old woman, Sarıbiyke G'anieva who

was born in Shımbay in 1918, told us that it was too expensive to hire a ko'k ko'ylek for her own wedding in the 1930s, so she

wore a pashshayı ko'ylek instead.

However, according to Ag'ınbay Allamuratov, their use originally extended beyond the wedding ceremony. He wrote that they were worn by 15

to 16-year-old girls for festivities and in the case of some women, presumably those of high status, even for everyday wear. Allamuratov realized

that the ko'k ko'ylek was unusual because young Karakalpak girls and women normally wore red clothes.

Like the associated sa'wkele, ko'k ko'yleks seem to have been in use throughout most of the 19th century, becoming increasingly

rare during the early years of the 20th century. Even so we known from certain museum pieces that ko'k ko'yleks were still being

embroidered up to about 1920 in fact the last one we know of was made between 1926 and 1930. One reason for their demise may have been the

increasing availability and popularity of red and black woollen felted ushıga, and the associated qızıl

kiymeshek wedding costume. By the 1920s this had gained almost universal popularity among young brides.

|

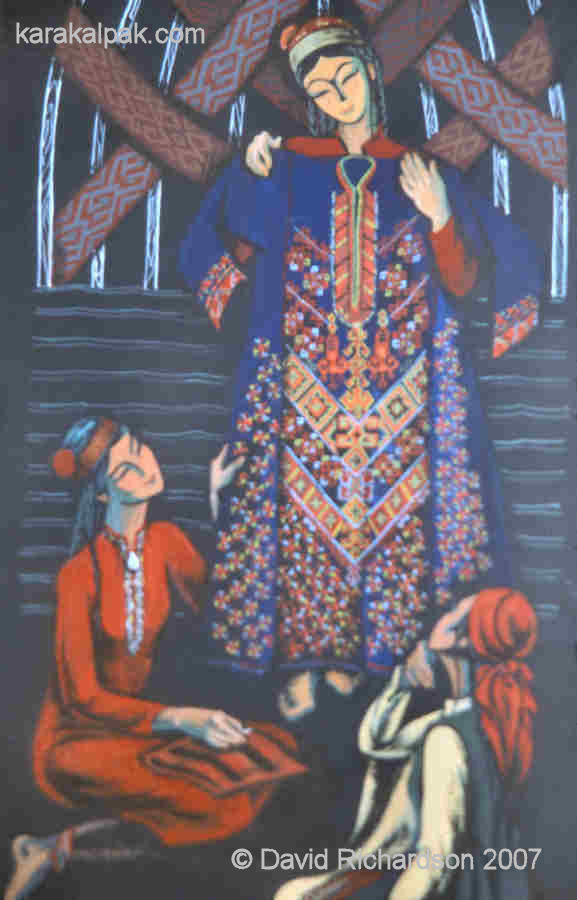

In museum collections and published photographs ko'k ko'yleks are sometimes displayed in combination with the sa'wkele and

the chain-stitch qızıl kiymeshek and jipek jegde. The sa'wkele was not only contemporary with the

ko'k ko'ylek but was also exclusively restricted to the wealthy elite, so it is likely that during the 19th and possibly 18th centuries

these two items were worn together for marriage and other ceremonies even though we lack firm historical evidence. However the chain-stitch

qızıl kiymeshek only gained popularity towards the very end of the 19th century, just as the ko'k ko'ylek was

becoming obsolete. Some Karakalpak informants claim that the sa'wkele was worn over a red kiymeshek, so it is possible that

the ko'k ko'ylek and the qızıl kiymeshek may have been worn together for a couple of decades. However, throughout

most of the 19th century, the ko'k ko'ylek could not have been worn with a kiymeshek embroidered in chain-stitch. Sadly we have

no information to say how it was actually worn at that time. We do however know that, as elsewhere in Central Asia, it was a sign of status to

wear many layers of clothes. The Karakalpak tradition was for a wealthy bride to wear five layers of clothes, known as a bes kiyim

(literally five clothes), so the ko'k ko'ylek was most probably worn with several other items of costume.

Only small numbers of ko'k ko'yleks have survived the rigours of repetitive long-term use to remain with us today. The one exception is

the example from Shege, which should perhaps be regarded as an exhibition piece, made as a special embroidery project rather than as part of an

ongoing tradition. More recently some Karakalpak embroiderers have displayed their embroidery skills by producing more modern versions of ko'k

ko'yleks, although the quality of their work bears little resemblance to that found in the traditional examples. The Karakalpak embroiderer

Nesibeli Nagenova even won first prize in the "Voice of Asia" competition in Almaty in 1990 with her modern ko'k ko'ylek. At the beginning of 2008

reproduction ko'k ko'yleks began to emerge from Bukhara, embroidered in chain- rather than cross-stitch for the tourist market.

The ko'k ko'ylek is unique to the Karakalpaks. No similar item of female costume or style of decorative embroidery has been found among

the neighbouring Uzbeks, Turkmen, Qazaqs, Kyrgyz, or Tajiks.

However there are similarities between the Karakalpak ko'k ko'ylek and some of the traditional dresses worn in the past by the Ugric

peoples from the Ob River in northern Siberia. See below.

Terminology

Ko'k ko'ylek simply means blue dress. They were occasionally called xalıqları ko'ylek (people's dress), boyaq

ko'ylek (dyed dress) or kesteli ko'ylek (embroidered dress). In the Latin transliteration from the Russian Cyrillic alphabet it is

spelt kok koylek.

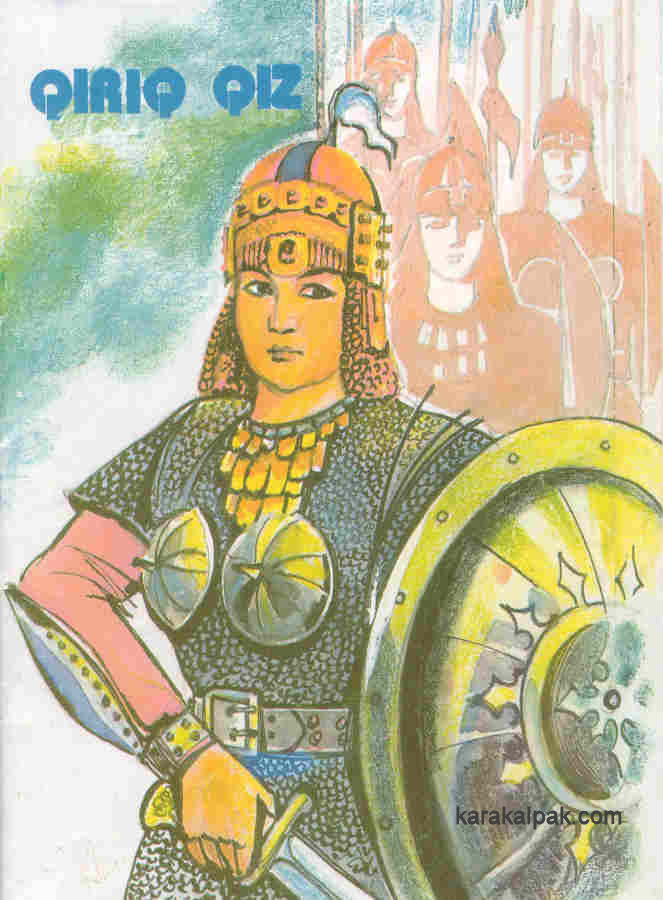

The embroidery patterns on the ko'k ko'ylek were described by Ag'ınbay Allamuratov, who studied Karakalpak embroidery for his Ph. D.

thesis (which was never completed and seems to have been lost). He subsequently published a monograph on the same subject. Much of his research

involved interrogating local women throughout Karakalpakia about the different embroidered costumes and the embroidery patterns associated with them,

together with their meaning. Many Karakalpaks described the embroidery pattern on the front of the ko'k ko'ylek as

the sawıt nag'ıs, meaning armour pattern. Allamuratov likened this pattern to a suit of chain-mail and linked it to the epic poem

Qırq Qız (Forty Girls) and the imagined costumes of early Massagetae women warriors. The same fanciful connections have been made for

the sa'wkele. see Mythology of the Sa'wkele.

|

Personally we find it hard to see any similarity between the decoration on the front of a ko'k ko'ylek and the rows of small plates on a

suit of chain-mail. However it is possible that the association with armour comes from the dresses' spiritual, rather than physical, protective

powers see below. Other scholars have likened the pattern to the tree of life or o'mir darag'ı design.

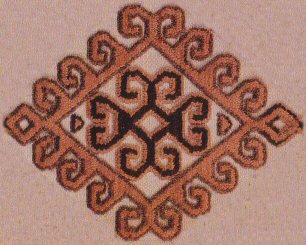

The range of motifs included in the decoration of ko'k ko'yleks is quite limited and proscribed. The two main motifs that occur most

frequently are segiz mu'yiz and at ayıl nag'ıs:

|

Minor motifs include qos mu'yiz, piskekshe and g'az moyın:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Motifs that occur regularly but in small numbers include sırg'a nag'ıs, Xorasanı mu'yiz, and g'arg'a tuyaq.

The central sırg'a nag'ıs or earring pattern occurs on three of the Savitsky ko'yleks and on the one from Saint

Petersburg. There are normally three motifs, the central one larger than the other outlying two. Some have likened these three sırg'a

nag'ıs motifs to a mother and her two daughters.

|

|

In some designs the central earring motif is combined with a vertical row of g'arg'a tuyaq or crow's foot motifs. The exception is the

Saint Petersburg example, which has six sırg'a nag'ıs motifs. One or two bold Xorasanı mu'yiz motifs were often

placed in the centre of the sawıt nag'ıs pattern.

|

It should be noted that the sawıt nag'ıs pattern is not unique to ko'k ko'yleks. Very similar chevron-like cross-stitch

decorations also occur on aq jegde.

Folk Beliefs

The use of blue for a wedding dress is unusual, because blue was the colour of mourning for many Central Asian people. Consequently it was

traditional for a Karakalpak widow to wear a plain undecorated blue dress. Indeed there is a Karakalpak folk song that tells a story about

certain events following the death of the Prophet Mohammed. His blue flag was torn apart and out of the fragments the women made blue dresses as

a sign of respect. From that time onwards, so the song goes, blue clothes have always been worn as a sign of mourning. According to Aygu'l

Pirnazarova, Curator of Costume and Jewellery at the State Museum of Art, No'kis, and the ethnographer Xojamet Esbergenov, plain blue

dresses were only worn by a woman in mourning for a few days, after which she switched to a white dress. The colour blue was considered to be

so powerful that its continued use might risk the death of a second individual.

By contrast clothes for Karakalpak girls and young women were almost universally red. Having said this we know that Karakalpak women wore both

red and blue long-sleeved dresses during the 18th century see History. Allamuratov was so mystified by this conundrum that he

wondered whether the blue colour of the ko'k ko'ylek may have had some ritual significance as yet not fully understood.

Although the complex embroidery decoration on the front of the ko'k ko'ylek had little physical likeness to a suit of armour, it was

considered to have amuletic powers, protecting the young bride from the envious evil eye. As a consequence the ko'k ko'ylek was revered

for its mystical special powers. For example, sick people were sometimes treated by a shaman by enveloping them in smoke using smouldering pieces

of ko'k ko'ylek. People also believed they would benefit from the longevity of an old female relative. On her death, fragments would be

cut from her ko'k ko'ylek to be shared among members of her surviving family. This may be the reason why some surviving ko'k

ko'yleks have had all or part of their sleeves removed.

At the same time some elements of the sawıt nag'ıs pattern may be associated with fertility. The diamond containing a cross

is an ancient motif, considered by some scholars to represent the female vulva. Furthermore the abundance of mu'yiz patterns might symbolize

fertility and prosperity in a livestock-breeding culture. As L. I. Rempel observed in 1970: "The mu'yiz motif is the symbol of the

productivity of livestock breeders, ..."

Museum Collections

Today ko'k ko'yleks are extremely rare and only a handful of examples are known - four in

the State Museum of Art named after Igor Savitsky, No'kis; one in the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis;

and one in the Russian Ethnography Museum, Saint Petersburg. For detailed information on visiting the museums in No'kis see

our Sightseeing page.

It is possible that a few other examples exist in museum funds in Saint Petersburg Marinika Babanazarova once told us she thought there might be

five in total, suggesting that there could be up to four yet to be accounted for. We have already mentioned the second ko'k ko'ylek

purchased from Aq Darya, whose current location remains a mystery, and we shall refer below to another unidentified example described by Esbergenov.

|

It was purchased from Qayıpbergen Jamuratov (a man) from the Second Department, Second Brigade, Qarao'zek region. No other information was recorded.

|

The patterning on this ko'k ko'ylek is quite simple with only four lines of definitive chevrons, their width increasing from the bottom

chevron to the upper chevron. The latter contains the central sırg'a nag'ıs decoration, which is bold and very angular.

The first and third chevrons incorporate at ayıl nag'ıs motifs, while the second and fourth incorporate segiz mu'yiz

motifs. The first three also each contain a central Xorasanı mu'yiz motif. Although there are further segiz mu'yiz motifs arranged

diagonally above the fourth chevron, they are not delineated into rows. The embroidery below and to the side of the chevrons consists of a uniform

diagonal lattice of simplified or stylized segiz mu'yiz motifs constructed from a central square surrounded by eight rectangular hooks.

The front seams have been overembroidered in omırtqa or vertebrae decoration.

|

The vertical opening below the small v-shaped collar is decorated on either side with small diagonal rows of triangles with rectangular horn-like protuberances. These are arranged symmetrically. The sleeves are mainly plain with the decoration confined to the area above the cuffs.

|

It was purchased on an unknown date from Orazgu'l Da'wletmuratova, from Brigade Number 1, Taxta Ko'pir sovxoz, Taxta Ko'pir.

According to Allamuratov this ko'k ko'ylek was actually made by Orazgu'l herself, who was born in 1901. This suggests that the dress

was probably made in the late 1910s.

|

The chevrons on this dress run from just above the bottom hem, with its row of qos mu'yiz and a diagonal lattice of simple segiz

mu'yiz motifs above, to just below the shoulder. The bottom six chevrons alternate between at ayıl and more complex segiz

mu'yiz motifs, the final sixth chevron incorporating the sırg'a nag'ıs motifs. Above this the chevrons are simpler,

alternating between rows of diamonds with crosses and double rows of qos mu'yiz.

The segiz mu'yiz on the two front side panels are arranged in horizontal rows separated by rows of x-shaped crosses.

|

The collar has been edged with narrow strips of red and black ushıga, divided by a line of gold zari work and embroidered

in chain-stitch around the neck opening with qumırısqa bel and qos mu'yiz motifs. The outermost edge is finished

with a narrow border of raspberry red jiyek. The cuffs are decorated with a zigzag and triangles composed of one half of the at

ayıl motif. This is finished on the upper side with a row of fish-spear motifs and at the cuff edge with a strip of plain red

ushıga edged with more gold zari work.

A slit pocket and the lower side vents are edged with red jiyek.

|

Although the body of the dress is in good condition, the sleeves have been completely removed, possibly following the death of Sa'senem.

|

In this example the lower front part of the dress is covered with a diagonal lattice of alternating at ayıl and segiz mu'yiz

motifs. The column of chevrons only commences at mid-thigh height and extends up to shoulder level, every alternate chevron containing at

ayıl motifs. The three sırg'a nag'ıs motifs are roughly the same length and all include some g'arg'a

tuyaq or crow's foot motifs. The two front side sections are different, one decorated with a scattering of segiz mu'yiz motifs, the

other with an inverted tree of life (somewhat like an aq jegde decoration). A row of tikesh bread-stamp motifs runs just above

the bottom front hem.

|

The collar opening is finished with a narrow strip of red ushıga edged with gold braid, the upper section around the neck opening

embroidered in chain-stitch with solaq motif. A narrow band of cross-stitch embroidery decorates each side of the vertical neck opening,

using a pattern based on diagonal rows of small triangular teeth, some with rectangular horn-like protrusions.

The two side vents have been edged with red jiyek, which has been overembroidered at the top. However the joints between the vertical

strips of blue bo'z have not been concealed with embroidery.

|

It was purchased in 1967 from Maria Abdieva. There is no record of its geographical or tribal origin or its date of manufacture.

|

Despite its condition it is clear that the chevron design stretched from the v-shaped collar opening all the way down to just above the lower hem,

the rows above the sırg'a nag'ıs motif being narrower than those below. The central sırg'a nag'ıs

motif is longer and narrower than the outer two and is composed mainly of g'arg'a tuyaq elements. There is a single Xorasanı mu'yiz motif in the centre at the bottom of the dress.

The cross-stitch decoration on the two front side panels is quite limited. Note that the decoration around the vertical collar opening is unusually asymmetric.

The upper collar is made from a strip of black ushıga, embroidered with rows of triangular teeth. It is lined with natural cotton

bo'z.

Mysteriously there are the remains of small embroidery motifs on one of the sleeves but not on the other.

|

We do not know whether it was actually worn by Nesibeli for her wedding. The dress is very black in colour and is clearly in very good condition,

although there are a few holes in the sides.

Although the dress contains many features found in the traditional ko'k ko'yleks it also includes some imaginative elements, suggesting

that it may have been made as a special embroidery project rather than as an attempt to faithfully reproduce a copy of the traditional 19th

century garment.

The front panel of the dress is decorated with a typical sawıt nag'ıs pattern from the bottom of the hem to shoulder height, with alternating

chevrons of at ayıl and segiz mu'yiz towards the bottom, smaller diamonds further up and qos mu'yiz motifs at

the very top. The seams are overembroidered with the omırtqa vertebrae motif.

|

However the normal sırg'a nag'ıs earring decoration has been replaced by simpler horn-like motifs coupled with a few

g'arg'a tuyaq crow's feet. The two side panels are different from each other and both contain an unusually wide selection of designs

including diagonal rows of at ayıl motifs. The v-shaped neck opening is edged with black ushıga, decorated in

chain-stitch with rows of qumırısqa bel and solaq motif, while the vertical lower collar opening is decorated on

either side with a band of at ayıl motifs in cross-stitch. The entire neck opening is edged with raspberry red jiyek.

|

It was probably collected in the early 1930s, since the inventory number shows that it originally belonged to the Dashkov Museum in Moscow, which

was closed by Stalin in 1934. In the early 1940s the contents of this museum were sent to Saint Petersburg.

|

|

The front panel of the dress has a typical chevron design, which stops some distance above the bottom hem. The chevrons in the lower part of the

dress alternate between rows of at ayıl motif and rows containing qos mu'yiz and piskekshe motifs. The upper

chevrons alternate between rows of large and small segiz mu'yiz motifs. The central sırg'a nag'ıs decoration is

unusual since it includes six rather than three earring motifs. The lower part of the front panel and the two side panels are covered with a lattice

of alternating segiz mu'yiz and piskekshe motifs. Some but not all of the joints between the strips of blue bo'z have

been overembroidered with omırtqa decoration.

|

The entire neck opening is finished with a narrow strip of red ushıga, an additional strip of black ushıga being

added to the upper collar. This has then been embroidered in chain-stitch with qumırısqa bel and other small motifs, before

being edged with raspberry red jiyek. A narrow band of cross-stitch embroidery decorates each side of the vertical neck opening, with

diagonal rows of small triangles arranged zigzag fashion, some of which have rectangular scrolled horns protruding from their tops.

|

The cuffs and lower parts of the sleeves are also extensively decorated with various bands of cross-stitch embroidery, including one similar to that

used along the sides of the vertical neck opening. The latter unusually includes some elements of green. The cuffs terminate with plain bands of

red and black ushıga that has been edged with red jiyek. The ushıga does not appear to be original.

"It was sewn from blue homewoven cloth. The cut is free and straight and it has seamless shoulders. The sides have small cuts at the bottom. The sleeves are long and wide with triangular gussets. The neck opening and the cut on the breast part are edged with a strip made from red cloth and raspberry coloured jiyek. This strip is embroidered with silk threads in a green colour using cross-stitch. A narrow strip of black cloth is stitched onto the red strip along the neck opening and is embroidered with curls in different coloured silk threads. The front part of the gown is embroidered using cross-stitch in red, yellow, green, and white silk threads. The pattern is geometric and consists of sloping rows of diamonds, squares, curls, and other figures. The cuffs are sewn around with raspberry coloured jiyek and the insides are lined with striped cotton cloth. The length of the ko'k ko'ylek is 143cm, the width of the bottom edge is 90cm and the length from cuff to cuff is 166cm."We have yet to discover the location of this example.

|

Muravin's observations were confirmed by Peter Pallas, who in 1767 left Samara and crossed the Volga and the Yaik (Ural River) to visit the Qazaqs

of the Lesser Horde on the North Caspian Steppe. He observed that the common costume of the Qazaq women was a blue shirt with a blue front, which

at home they wore with nothing else over it.

In her review of links between the Karakalpaks and Bashkirs, Tatyana Zhdanko suggested that the colour of the ko'k ko'ylek may have been

determined by the widespread availability of commercial blue-dyed cotton during the 18th and early 19th century, since cotton-growing was probably

not yet developed as part of the Karakalpak economy at that time. Zakharov and Khodzhayeva had already noted that Qazaq women predominantly wore

blue cotton dresses during this period and that similar dresses were worn by the Bashkirs, Karakalpaks, and people of the southern Altai. This was

attributed to "the abundance of cheap cloths of this colour, which were being brought from Central Asia". Zhdanko's ethnographic team had also been

informed by elderly Karakalpaks that in the past the ko'k ko'ylek was made from domestically produced linen known as torqa, woven

from the fibres of wild hemp (qızıl kendır), which grew extensively in the wetlands of the Aral region. She postulated

that the availability of indigo-dyed bo'z had eventually replaced the use of homemade torqa. Bast fibre cloths were also

woven by the peoples of the Volga region and Siberia, such as the Bashkirs and the southern Khanty. We will discuss this issue and the links between

the Khanty and the Karakalpaks a little later.

The 1851 Khanykov edition of Gladyshev and Muravin's expedition contains no further description of Karakalpak costume. However it is not a complete

copy of the original 1741 report Khanykov only published 25 out of the 37 points made in Gladyshev's deposition. The late Karakalpak ethnographer

Kamal Ma'mbetov has published an additional quotation attributed to Gladyshev and Muravin, although without providing an exact reference:

"Young men were somehow dressed with torn shirts and without shoes. Girls were dressed in clothes that were dirty but richly embroidered, and on their heads they wore skullcaps. The decoration of their dresses was so bright that it hurt the eyes. We suppose there is a special cult of woman in this culture because so much attention was focused on them."If verified, such an observation suggests that the origin of ko'k ko'ylek-like dresses goes back to the time before the Lower Karakalpaks migrated into the Amu Darya delta.

|

From the information provided by Allamuratov it seems that the ko'k ko'ylek was a decorative festival dress worn widely by young Karakalpak

girls of marriageable age. Over time its use became increasingly restricted to the daughters of the wealthy, primarily for the purpose of marriage.

This change may have arisen as a result of the increasing impoverishment of the Karakalpaks following their subjugation by the Khivan Khanate. By

the time of the Russian conquest ordinary Karakalpaks were suffering considerable deprivation. Only a minority of modestly wealthy bays

could afford to maintain any semblance of their traditional material culture.

Local museum curators have expressed their belief to us that the reason that ko'k ko'yleks are so rare today is because of the past scarcity

and cost of natural indigo dye or nil. We are not convinced by this argument. Indigo was imported into the Khorezm region in huge quantities

from Persia, Afghanistan, and India and indigo-dyed bo'z was readily available on local markets. Riza Quli Mirza commented on the

availability of Shımbay-produced shanjala, which was a deeply dyed blue bo'z, on local bazaars around about 1874. Their

rarity is more likely due to the fact that, during the 18th and 19th centuries, only a small minority of wealthy bays could afford luxury

items such as ko'k ko'yleks and saw'keles. Of these only a small proportion have survived into the 20th century. Many more must

have become threadbare through use or were deliberately dissected following the death of their owners.

As a final topic we need to revisit the hypothesis of Tatyana Zhdanko, who suggested that at one time the ko'k ko'ylek may have been made

from torqa rather than blue bo'z. This idea seems to have initially come from elderly Karakalpak informants and may have been

reinforced by the fact that, in the past, Bashkir and somewhat similar Khanty dresses were woven from nettle fibre see below.

Torqa was a textile woven from the fibres of Siberian or clasping leaf dogbane, Apocynum Sibericum Jacquin, a sub-tropical

perennial that the Karakalpaks called kendır or more precisely qızıl kendır because of its red

bell-shaped flowers. It is a close relative of Indian hemp or cannabis, Apocynum cannabinum L.

Tomina investigated torqa cloth among local Karakalpaks in 1976 and discovered that in the past the stems of the qızıl

kendır plant were collected and retted in water to obtain the silver kendır fibres. These were fluffed up like wool and

then hand-spun into thread. The kendır yarn was woven on an o'rmek loom, the wefts being beaten down hard to produce a

heavy warp-faced fabric that was silver grey in colour, had a slight sheen and was almost waterproof. The finest torqa cloth was used to

make women's dresses, coarser cloth was used for men's shirts and trousers, while the heaviest cloth was used to make a durable khalat

called a torqa ton.

A dress made from such a strong material might be perceived to have had some of the qualities of armour. Indeed according to the Russian Ethnography

Museum, the Kyrgyz word torqa means a strong material, impenetrable to arrows.

Of course in the past hemp was used widely across Europe and Russia for the manufacture of textiles and clothing, especially durable working clothes.

From the Middle Ages to the end of the 19th century hemp was the second most important fibre after linen. In England in the 16th century Henry VIII

passed an Act of Parliament which fined farmers who failed to grow the crop. Levi Strauss actually made his first jeans from hempen cloth imported

from Nimes in France, hence the name "denim" which comes from "Serge de Nimes".

Linen made from hemp was also produced on the western fringes of Central Asia. Georgi noted in 1772 that the Bashkirs wove linen from both nettle

fibre and hemp, the latter being known as kinder. The nettle linen was coarse and used to make shirts. Peter Rychkov, who arrived in

Orenburg as a member of the Orenburg Expedition in 1732, was so fascinated by Bashkir stinging nettle cloth that he wrote two articles about it.

At roughly the same time the Tatars of Kazan were making thread from home-grown hemp. Somewhat earlier, in 1716, John Bernard Muller had found the

northern Khanty also weaving cloth from nettle fibre. By contrast Georgi found that the nomadic Qazaqs did not weave cloth from hemp or nettles,

but only from sheep and camel wool. Interestingly Nikolay Karazin commented on a forest of Indian hemp and sorghum growing close to No'kis in 1874.

Having said all this, no one has yet discovered a ko'k ko'ylek made from any type of bast fibre. Furthermore neither we nor any museum

curator in Karakalpakstan has ever seen a sample of Karakalpak torqa cloth. Many Karakalpaks we have spoken to remember seeing hemp

planted around the edge of fields it was thought to discourage Colorado beetle and other insects and some recall seeing hemp sackcloth.

Clearly some Karakalpaks believed that they once made dresses of torqa cloth, but whether this included ko'k ko'yleks we cannot

yet say.

Links with the Volga and the Ob

Cross-stitch embroidery is remarkably rare among the Turkmen, Uzbeks, Qazaqs, Kyrgyz, and Tajiks. It is much more common among the ethnic

groups inhabiting the Volga region, such as the Bashkirs, Chuvash, Mordvins, Mari, and Udmurts. Many of these groups also incorporate diamond

and horn-shaped motifs in their cross-stitch embroidery designs. Some also wore traditional dresses with embroidery decoration on the front.

Despite this however, none of these groups ever had a ceremonial garment similar to the ko'k ko'ylek.

Tatyana Zhdanko was the first to notice that the only other ethnic group to have a similar type of female dress to the ko'k ko'ylek are

the Ob-Ugrians the Ugric peoples living close to the Ob River in Siberia: namely the Khant or Khanty (previously known as the Ostyaks, now a

derogatory description) and the Mansi (previously known as the Voguls). Both have a dress with geometrical embroidery patterns positioned on the

front panels and the sleeves.

|

The southern Khanty and Mansi made tunic-shaped dresses, with the sleeves and the front embroidered using red and dark blue woollen threads. At the

end of the 19th century these dresses were made from kendyr or nettle cloth. The Khanty also wore a chest ornament around the neck,

somewhat similar to a Karakalpak o'n'irshe.

The Ob-Ugrians also used decorative geometric motifs that were similar to those that appear on the Karakalpak ko'k ko'ylek, such as

qos mu'yiz, segiz mu'yiz, qumırısqa bel, and the diamond containing a cross. Many of these were identified

by the Siberian researcher Sergey Ivanov in 1963.

The traditional homeland of the Khanty is the region stretching from the mouth of the Ob in the north to the confluence of the Irtysh in the south,

and from the northern Ural Mountains in the west to the heart of Siberia in the east. The Mansi live to their north-west, in a territory extending

westwards across the Urals and southwards to the Chosva River. The Khanty and the Mansi have lived in close proximity to each other for a considerable

time and although their languages differ, their way of life, customs, costume, and dwellings have many similarities. However there are important

differences. The northern Khanty are reindeer herders, the eastern Khanty live in the forest zone, while the southern Khanty are more pastoralist

- in the past they raised cattle and kept some sheep.

It seems surprising to find an apparent cultural link between the cattle-breeding, fishing, and agricultural Karakalpaks of the Amu Darya delta and

the cattle-breeding southern Khanty living 2,500 km further north in the frozen taiga and forest tundra of Siberia, especially given the radical

difference between their spiritual and material cultures.

|

We know that the Karakalpak confederation became very dispersed during the 17th century and that some Karakalpaks were present in the southern

Siberian region of Tobolsk. For example, in 1690 and 1691 Karakalpaks participated in attacks on a stockaded town in the Tyumen region of Siberia

and on settlements along the river Tobol. It is therefore quite likely that some Karakalpaks came into contact with the southern Khanty.

An alternative and perhaps more likely explanation is that both ethnic groups were influenced by a common third party, such as the Siberian Tatars.

There has been constant interaction and trade between the southern Khanty and the steppe nomads throughout history. As early as the 1240s the

Khanty and the Mansi territories came under the control of the Mongol Khan Shayban, who was allocated a vast tract of pasturage in western Siberia

as a reward for his loyal military service in Hungary. In time the Khanty and Mansi people began to come under increasing Turkic influence. From

the mid-14th century onwards, the Shaybani Horde adopted the appellation Uzbek and during the 15th century they began a southern migration under the

leadership of Abu'l Khayr Khan. The remaining Tatar tribes consolidated to form the Khanate of Sibir, with its centre located close to present-day

Tobolsk and its political influence still extending across all of the Khanty-Mansi territories. By the 16th century the Khan of Sibir was depending

on Khanty, Mansi, Bashkir, and Mari forces in his struggles against the Russians but, after a Russian defeat in 1582, the Siberian Tatar leaders sought

refuge among the southern Noghay. After regrouping they made several successful counter-attacks against the Russians but were finally overwhelmed

in 1598. Over the following two centuries the Russians brutally abused the Khanty-Mansi, attacking their shamanist religion and forcibly converting

them to Christianity.

Traditional Khanty-Mansi clothing was made from a wide variety of fur skins, deer, elk, or reindeer hides and even bird and fish skins. However in

the southern areas they wove cloth from nettle and hemp fibres using primitive looms. The terms they use for weaving are similar to those of their

Tatar neighbours, so it seems likely that weaving was introduced as a result of contact with the Siberian Turks. They even use the terms non

for bread and khalat for coat.

The historical evidence suggests that the introduction of weaving had already occurred well before the end of the 17th century. Ysbrants Ides left

Moscow in 1692 on a three year journey to China and during his first year he visited the Ostyaks (Khanty) living on the River Ob. He observed that

the ordinary women wore neither linen nor woollen clothes, but dressed in a short coat and a cape made of fish skins. However when he visited a

local prince he saw that one of his young wives was bedecked in coral and wore a red cloth coat.

A little later, in 1716, John Bernard Muller wrote a monograph on the Ostyak people in which he indicated that their clothing was mainly constructed

from fish skins and wild furs. However he also recorded that Ostyak women used nettles as a fibre for weaving cloth. Furthermore they had a way

of decorating the cloth, possibly by the use of supplementary weft weaving or embroidery:

"..they have a way of preparing nettles, and make a sort of linen of it, ... . That Stuff, though it is very stiff, serves them also for Shirts and Head-cloths, the Ends of which they adorn with diverse Colours."When Johann Georgi visited the Tatars of Tobolsk in 1772 he noted that all of the women were weavers. Some Siberian Tartars had even settled along the river Ob and were following a very similar lifestyle to the neighbouring Ostyaks. It is therefore easy to see how Turkic weaving and possibly embroidery skills may have been passed on to the Ostyaks living along the river Ob.

|

According to Aksana Bogordayeva, in 1953 the scholar N. F. Prytkova proposed that the Ob Ugric shirt-dress originated as a result of the

influence of the Siberian Tatars, among whom female tunic-shaped dresses were common. However, in 1994 Ye. G. Fedorov suggested that they were an

adaption of the Russian sarafan. Bogordayeva concludes that their origins are more complicated. Tunic-shaped dresses initially developed

among the eastern Mansi and the southern Khanty and it was only later that they came under Russian influence. However such dresses only appeared

among the northern Mansi and Khanty at the start of the 20th century.

The link between the Karakalpaks and the Siberian Tatars is perfectly understandable in a historical sense. The Shaybanid Uzbeks had traditionally

occupied the steppes to the east and south-east of the Ural River, including the southern region of Turgay. In the summer they camped in the west,

in the vicinity of Orenburg, and in the winter they moved east towards the Sarysu. Under the leadership of Abu'l Khayr Khan (1428-1469), they began

to move south into Khorezm and the lower Syr Darya region. The close genetic and cultural relationship between the Karakalpaks and the Khorezmian

Uzbeks suggests that some of the tribal factions that eventually became part of the Karakalpak confederation may have also originated from this same

region of western Siberia. The inference is that the origin of the ko'k ko'ylek may be far older than we might think, going back to the

Siberian nomads who came under the control of Shayban Khan and his Tatar followers in the early years of the Golden Horde.

Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms

To listen to a Karakalpak pronounce any of the following words just click on the one you wish to hear. Please note that the dotless letter

'i' (ı) is pronounced 'uh'.

|

This page was first published on 11 March 2007. It was last updated on 6 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |