The Karakalpak Kiymeshek - Part 4

|

The Karakalpak Kiymeshek - Part 4

|

|

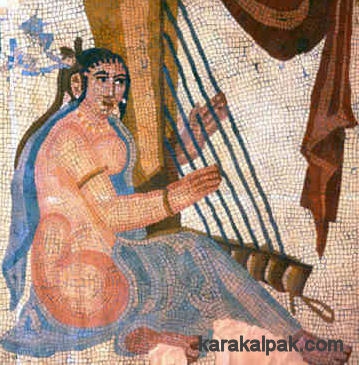

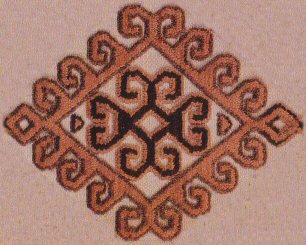

ContentsPart 1SummaryThe Karakalpak Kiymeshek Role of the Kiymeshek The Aq Kiymeshek The Qızıl Kiymeshek Part 2Different Qızıl Kiymeshek PatternsDistribution of Qızıl Kiymeshek Patterns The Dating of Qızıl Kiymesheks Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms References Part 3Other Kimeshek-Like GarmentsThe Qazaq Kimeshek The Uzbek Lyachek The Tajik Lachek and Kuluta The Turkmen Esgi, Lechek and Chember The Kyrgyz Elechek and Ileki The Khimar and Similar Islamic Veils References Part 4Previous Ideas on Kimeshek OriginsA Short History of Veiling up to the 16th Century References Part 5The History of the KimeshekWhere to see Karakalpak Kiymesheks References Previous Ideas on Kimeshek OriginsProfessor Sergey Tolstov, the pioneering archaeologist who founded the Khorezm Archaeological and Ethnographic Expedition, saw direct parallels between the material culture of the Karakalpaks, Qazaqs, Uzbeks, and Tajiks and that of the much earlier 2nd – 7th century Zoroastrian civilization of Ancient Chorasmia. The first phase of excavations at Topraq qala, a royal and religious summer palace located close to present-day Biruniy city, had just begun in 1947 and it is possible that Tolstov's excitement over the newly revealed wall paintings and ceramics simply got the better of him. In 1948 he wrote:"So the roots of modern folk art of the successors of the ancient civilization of Central Asia go back to extreme antiquity."In 1952 Tolstov made direct comparisons between the cut of Karakalpak national clothing, including female head wear, and the costume depicted in the wall paintings at Topraq qala. In particular he saw close similarities between the embroidery decoration on the qızıl kiymeshek and the patterns on the various female breast adornments, including one on an image of the goddess Anahita:

Comparison of decorations from Topraq qala (left) with those embroidered on a Karakalpak kiymeshek (right).

|

|

It is hard to see how a confederation of Turkic tribes, formed in the vicinity of the lower Syr Darya in the 16th century, could have had its

culture determined by a civilization that was obliterated by the Arabs in the 7th century. The costumes of the Khorezmian ruling elite depicted

at Topraq qala are a strange combination of male Saka and female Persian attire, with Hellenistic and Kushan influences, and even Mesopotamian

and Indian overtones, none of which are reflected in early 20th century Karakalpak costume.

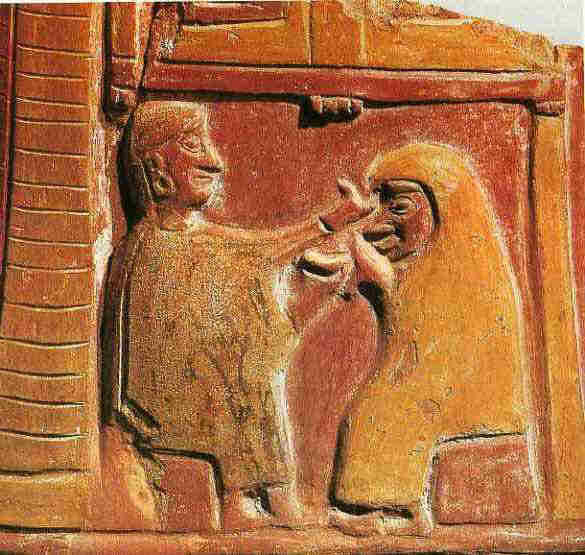

Anna Morozova proposed an alternative link to the ancient civilization of Sogdia in her 1954 discussion of the kiymeshek. She saw

similarities to the kiymeshek depicted on moulds for making terracotta statuettes found during excavations of Afrosiab, dated at that

time to the Kangui and Kushan periods (4th century BC to 4th century AD):

"The study of archaeological finds of Uzbekistan gives us the possibility of tracing ancient forms of this old clothing among the population of Ancient Sogdia. Among the moulds for statuettes mentioned on page 129 there were specimens of women figurines wearing a cloak with a breastplate which looked like a kiymishek."

|

Such figurines represented Anahita, the Avestan goddess of the heavenly waters and fertility, which were deliberately broken and replaced every

Navrus. Such cults were almost completely eradicated by the later Arab invasion.

In the absence of any explanation of how these two objects and cultures are connected across an expanse of two thousand years, we consider

Morozova's comment to be naïve.

Morozova went on to argue that at the time of Gladyshev and Muravin's visit in 1740, Karakalpak married women were wearing their shevkeli

above a broadcloth cape, which she clearly saw as an early form of the kiymeshek:

"The further description [of Muravin] leads us to conclude that women wore this headgear above their cover or cloak, which covered the chest and hung down the back with the corner pointing downwards ..."When commenting on Rossikova's observations about a qızıl kiymeshek in 1901, Morozova concludes that the kiymeshek: "had transformed from a heavy broadcloth cloak to a light cover from silk which more closely resembled headgear than outer clothing."

|

The Polovets stone statues or babas provide important evidence about the widespread use of plait covers, elaborate headdresses, and

tunics by the inhabitants of the southern Russian steppes west of the Volga in the 12th century. Yet the idea that the Polovets shoulder cape

would eventually evolve into the kimeshek seems far from convincing.

|

We must remember that the Polovets costume depicted in these statues is that of a localized and possibly derivative culture, formed through

ethnic mixing between the Qipchaqs, who entered the region in the 10th century, and the endemic population of Alans, Bulghars, Pechenegs, and

Oghuz, under the influence of the Kievan Rus. Rabinovich has previously noted that the custom of a bride completely covering her hair was already

prevalent among the southern Rus as early as the 9th century.

We already have clear evidence that high-status women in nomadic societies wore headdresses that concealed the hair, but not the face, as early as

the Scythian and Saka from 4th century BC archaeological finds in the Ukraine and the Altai – see Origins

of the Sa'wkele. We also know from an early miniature illustration in the Radzivill annals that the Polovets (Qipchaq) warriors who battled

against the Rus in the 10th century wore a bashliq cap, somewhat similar to the Saka felt cap with ear and nape covers. It possibly

indicates a remarkable degree of continuity in nomadic costume over this period.

However female head veils seem to have gone out of fashion among the western Asian nomads during the first millennium, as witnessed among the

Jety Asar, direct descendants of the Apasiaks. This is particularly noticeable following the arrival of the Turks. In the early 10th century,

Ibn Fadlan found that Oghuz and Bashkir women went unveiled. During the 13th and 14th centuries, Western observers such as Pian di Carpini and William of

Rubruck recorded no such costume among the nomads occupying the Qipchaq steppe. When ibn Battuta visited Anatolia in 1330 he found that the wives

of the Seljuk Turks did not practice veiling. In 1334 he too travelled across the Qipchaq steppes to visit Őzbeg Khan on the Volga and discovered

that:

"... the womenfolk of the Turks do not veil themselves. Not only royal ladies but also wives of merchants and common people will sit in a wagon drawn by horses. The windows are open and their faces are visible."If we want to find an origin for the kimeshek, perhaps we need to look at developments in the settled rather than the nomadic world.

|

The rite of veiling the bride (known as pussumu) was also an important part of the marriage ceremony in Babylonia, as evidenced by

Karel Van der Toorn.

In the second millennium the neighbouring Hittites may have adopted the same practice. Two Old Hittite teracotta relief vases found at Inandik

and Bitik, close to Ankara, depict possible marriage ceremonies. In the first a bride and groom sit on the marriage bed as the husband raises

his hand to remove the bride's veil. In the second a cloaked man and woman sit inside a portico, the man having just offered the woman a drink

before lifting her veil with his hand.

|

Maurits van Loon has concluded that in ancient western Asia, "the public part of a wedding probably culminated in the removal of the bridal veil".

Veiling also seems to have been widespread among higher status women in Assyrian society and eventually became regulated under Tiglath Pileser I

(1115-1073 BC). German archaeologists discovered his Middle Assyrian Code at Assur in Iraq in 1903, inscribed on 15 clay tablets. Otto Schroeder

finally translated these in 1920. The code made it obligatory for women of marriageable age, mothers, and other free women to cover their head with

a veil in public, or indeed at home in the presence of non-related males. By contrast prostitutes or unaccompanied slaves were forbidden to veil

themselves and penalties for breaching the code were severe. The veil was therefore partly a symbol of status and partly a symbol of a woman's

sexual non-availability.

In ancient Greece veiling in public or in the presence of unrelated males ceased to be a practice confined to the elite but extended to women of

varying social strata. Girls were veiled from the age of puberty, but at the time of marriage they would don a bridal veil, or kredemnon,

which was generally reddish in colour. At the completion of the marriage ceremony the bride was revealed to the wedding party through the

ritual known as the unveiling or anakalypteria.

|

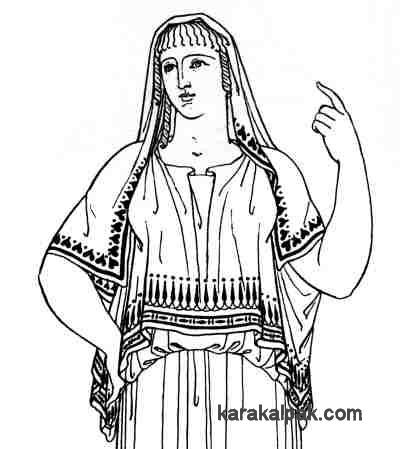

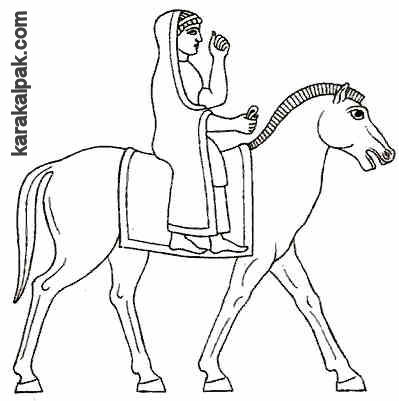

In Persia early female fashions are hard to study because of a severe shortage of historical figurative material - official monuments such as

Persepolis do not include representations of women. However a number of Achaemenid relief sculptures discovered at the mausoleum or temple of the

local Lydian satrap at Daskyleion, close to modern Ergili in Anatolia, show a procession of women on horseback, possibly part of a funeral

procession. The women are dressed in a long overgarment which veiled the head and neck but left the face exposed in a similar way to a modern

chador:

|

The so-called "satrap sarcophagus" from Sidon in southern Lebanon, which dates from the late 5th centuty BC, depicts the wife of another local

satrap at a banquet, also wearing an all-enveloping cloak covering all but the face:

|

Images of women also appear on numerous Achaemenid seals, statues, and figurines. These show some women clothed with partial veils and others

crowned without a veil. For example, a 5th century BC chalcedony seal shows an enthroned woman wearing a veil surmounted by a turreted crown.

It appears that the Achaemenid veil was not a universal requirement for married women but was a symbol of the status of aristocratic women.

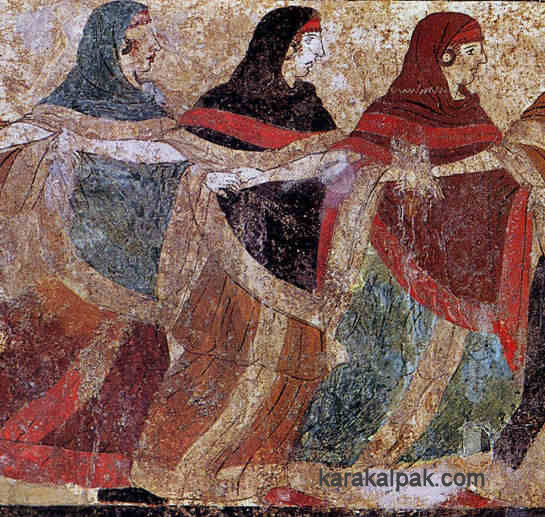

A tapestry recovered from a 3rd century BC Pazyryk burial, thought to be Achaemenid, shows a repetitive motif of four women gathered on either

side of an incense burner. All four wear pointed crowns, the two in the foreground having long veils suspended over the very back of the crown,

falling down their backs to reach their thighs.

|

Early Roman costume was influenced not only by the Greeks but also by the Etruscans from southern Italy. From the latter they inherited the

tebenna, a rectangular or semicircular shawl that eventually evolved into the toga. This was originally made from coarse

undyed wool, but eventually became lighter and decorated with a contrasting border. It seems to have been an almost universal item of costume

for women (and for men), worn with one end wrapped over the head.

|

In Roman culture a bride was dressed for her wedding in a mantle, part of which was draped over the top of her head. Several Herculanium statues

depict this palla or large mantle, draped to cover the back of the head. In the later Imperial Period, 44 BC to 410 AD, the Roman bride

wore a large rectangular saffron yellow flammeum. Married women were expected to cover their heads in public as a sign of their marital

status. The Roman verb for marrying, nubo, is related to nubes, a cloud, literally "I veil myself". From this comes

nupta, a married woman, nova nupta, a bride, nuptiae, the wedding, and of course the English word nuptial. Removal of

the veil was seen as a symbol of withdrawing from the marriage and an unveiled married woman received less protection from the law in the event

that she was raped or molested.

The ritual of veiling the hair of a married woman became incorporated into both early Jewish and Christian cultures during the period of Roman rule.

|

|

The Byzantine Empire, which evolved out of the Roman Empire, its capital city having been founded by the Emperor Constantine, inherited Roman

dress culture along with the practice of veiling. As Dawson has recently pointed out, the history of Byzantine costume is still far from clear,

although it does seem that veiling the head with various types of scarves was commonplace at different social levels, although the practice

remained entirely voluntary. The veil even became a symbol of sexual innocence or abstinence, placed over the heads of young girls and images

of the Virgin Mary.

In Parthian Iran (250BC-224AD), women were also rarely represented in reliefs or sculptures. From the limited material available, women are depicted

wearing a Hellenistic style of dress. For example, the "Goddess of Nisa", recovered from the Parthian capital on Nisa, is dressed in a chiton

and peplos with a scarf across her chest:

|

In other instances women are shown with a veil covering just the back of the head.

Under the Sasanians (224-651AD), the head veil continued to be worn but was far from universal. Women are depicted on silverware plates and flasks

wearing a smaller veil or scarf falling in narrow folds to just below the shoulder blades or simply draped around the neck like a collar.

In the 3rd century AD wealthy and powerful women as well as ordinary commoners are depicted wearing head shawls either fastened at the shoulder or

draped over the head. However many women are shown with their hair uncovered.

|

|

One popular female fashion that emerged during the Sasanian period was the bandeau, a pair of long, flowing ribbons fastened to the back of the head

with a very large knot.

|

The emergence of Islam in the 7th century led to major political and economic changes throughout western Asia, including the creation of a huge

geographic zone of common culture and international trade. In time it would also lead to the emergence of an almost general style of Islamic dress,

albeit with certain regional variations. In the short term however, it had little effect on female costume and veiling.

The Prophet Muhammad was born in the city of Mecca in Arabia in 570. In the last 20 years of his life, before his death in 632, he was inspired

by divine messages and visions from which he laid down the foundations of the Islamic faith. These were later encoded in Arabic as the Qur'an,

or Recitation (of God), under the supervision of Abu Bakr, the first caliph.

Following Arab unification, Abu Bakr ordered his forces to invade Byzantine Syria before embarking on a major campaign against Sasanian Iran in

633. By 637 Mesopotamia and Iraq were under Arab control and in 642 the main Sasanian army was routed in western Iran. Arab armies moved on to

take Seistan before sweeping through Khurasan, progressively taking Nisa, Saraqs, Herat and Merv. Attempts to conquer Byzantium, however, never

succeeded. The momentum to subjugate Central Asia took longer to gather, but by 714 the Arab caliphate had extended its rule over both Khorezm

and Transoxiana, the Arabs referring to the latter as Mavara'l-nahr or Mawaran-nahr, the lands beyond the river, in other words

the Amu Darya. There was strong resistance to Arab rule and to the imposition of Islam throughout these new territories, resulting in a century

of rebellion and uprisings. Despite these struggles, local elites were gradually won over and converts were rewarded with tax and other incentives.

By 850 most of the towns of Mawaran-nahr and Khorezm had converted to Islam.

Despite the enormous current publicity relating to Islam and veiling, the phenomenon of face veiling seems to have emerged several centuries

after the death of Muhammad. In line with neighbouring regions late 6th century Arab custom required both men and women to cover their heads

as a mark of modesty and respect, especially when at prayer. This was achieved in a simple manner, either with scarves or by raising a body wrap

or mantle over the head.

The Qur'an makes a number of brief comments about dress code. In one it refers to the khimar, instructing female believers to use it to

cover their bare breasts. At that time the khimar was probably no more than a headscarf with its ends crossed under the chin and thrown

back over the shoulders. The Arabic word khimar simply means cover and its plural is khumur. Verse 31 of the 24th surah

of the Qur'an, Surah an-Nur, reads:

"And say to the faithful women to lower their gazes, and to guard their private parts, and not to display their beauty except what is apparent of it, and to extend their khumur to cover their juyub [breast cleavage], ..."It seems likely that the khimar may have already been in existence for at least one or two centuries beforehand, since the rayt, a nickname for the khimar, is mentioned in at least one pre-Islamic poem - written by Imru al-Qays, who died in about 550.

"O Prophet! Tell thy wives and daughters, and the believing women, that they should cast their jilbab [long shirtdress] over their persons [when abroad]: that is most convenient, that they should be known [as such] and not molested."However it seems that it took several centuries for this recommendation to gain widespead support throught the Islamic world. The late Yedida Stillman recently reviewed the phenomena of veiling during the early Islamic period, observing that:

"... strict veiling practices probably evolved as the norm for middle and upper class women over the first two centuries of the Islamic era in the cities and towns of the caliphate, ..."Unfortunately, there is a major shortage of detailed evidence to track changing fashions over this and subsequent periods up to the 18th century. The majority of surviving written records concentrate on military conquests, religion, geography, and trade, with only minimal references to textiles or costume. We have to rely mainly on examples of figurative art, which is of course subject to artistic licence and was not only produced for the social elite but frequently depicted their life at court and at play. Only rarely do we get a glimpse of the common people. The use of such material is based on the assumption that the costumes portrayed represent the age in which they were painted.

|

However other female figures depicted in the frescos wear full length dresses and head veils that fall below the shoulders:

|

To what extent these latter fashions represent the costumes actually worn throughout the wider caliphate is impossible to judge. However the frescoes

at Qusayr 'Amra do point towards a much more liberal mentality among the ruling elite of the time. Nonetheless stricter forms of female veiling had

clearly not disappeared. One indication is provided from the palace of Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi in Syria, south-west of Palmyra, and redeveloped by the

caliph Hisham in 727. It contains murals combining Sasanid, Byzantine, and Syrian styles. One depicts a woman's headdress consisting of a turban

wound with a length of material surrounding the face, which could also serve as a veil. We can find no similar example among the limited number of

depictions of Sasanian women dating from that period.

Veiling seems to have become a far more established practice for high-status women under the Abbasid caliphate (750-1258), which relocated to

Baghdad in 762. As such, the caliphate came under the increasing influence of Sasanian Iran, although it still maintained cultural contacts with

Egypt and Byzantium. However the emphasis on veiling still seems to have taken some time to emerge.

|

During the 9th and 10th centuries the court of the caliphate became increasingly fashion-conscious - a trend that became even stronger in

neighbouring Egypt under the Fatimid dynasty. Al-Muqaddasi noted that the people of al-Iraq like to dress well. The Baghdad writer

Abu i-Tayyib Muhammad al-Washsha, who died in 936, published Kitab al-Muwashsha' aw al-zarf wa-l-Zurafa', the "Book of Ornamentaion on

Elegance and Elegant People" describing the outdoor clothing of a fashionable woman. This included the mi'jar, a cloth wrapped around

the head, and the miqna' or miqna'a, a simple rectangle or semicircle of netting covering the face and falling to the shoulders,

in some cases being gathered below the chin. He was particularly impressed with the miqna'a face veils of Nishapur.

This trend towards increased veiling was not a phenomena restricted to the Islamic world since it also occurred across Christian Europe. The

popularity of head veiling steadily increased from the 7th century onwards. In the 10th century the headrail became fashionable, a long

shawl that was draped over the head, wrapped around the neck and passed over the shoulder. The wimple or couvrechef is first

recorded in the 12th century and was worn under a large rectangular head veil. The barbette and the gorget neck cover appeared

about the same time. By the 13th century the rectangular veil or peplum worn over a wimple had almost become universal. Possible

reasons for these common trends were the strong influence of Byzantine fashion on both the West and the Near East and, after the 11th century,

descriptions of Muslim fashions brought back to Europe by the returning crusaders.

|

The creation of the semi-autonomous Samanid state in 900, with its capital in Bukhara, marked the end of Arab rule in Central Asia and created

closer ties between Khurasan and Mawaran-nahr that lasted throughout the entire 10th century. The Samanids created a strong, partly

centralized, partly federal state that provided stability and encouraged craftsmanship and trade. In 921 it was possible for an Islamic embassy

representing the caliph Muqtadir to pass from Baghdad, through Khurasan to Bukhara and then into Khorezm before venturing on to the Volga. The

King of the Volga Bulghars wanted to create an Islamic state as a bulwark against the Khazars and required assistance. Ahmed ibn Fadlan, the

secretary to the embassy, coped well in Bukhara and Gurganj apart from the cold. However he recorded that the nomadic Turks between Khorezm and

the Volga, such as the Oghuz and the Bashkirs, showed little modesty and that their women went unveiled. On the Volga he bemoaned that his

unceasing attempts to encourage the women to veil themselves in public proved fruitless. Sadly he left no account of the veiling fashions of the

women of Bukhara or Gurganj.

The 10th century authors provide some indication of the widespread production of kerchiefs, shawls, and veils throughout the Islamic world,

including parts of western Central Asia. Al-Muqaddasi recorded that Merv, Jurjan in northern Iran, and al-Askar in Khuzistan specialized in

the production of silk veils, some for export to Baghdad and the Yemen. In Khorezm they produced veils of malham as well as cowl head

covers. Veils also came from Ramla, the capital of Palestine, Nishapur, and Siraf in Fars, the latter making them from linen. The

Hudûd al-Âlam (982) records that burqa' were made in the borough of Baylaqan in Arran, today part of Azerbaijan.

Writing sometime before 1224, Yakut mentions Sarakhs as another important centre.

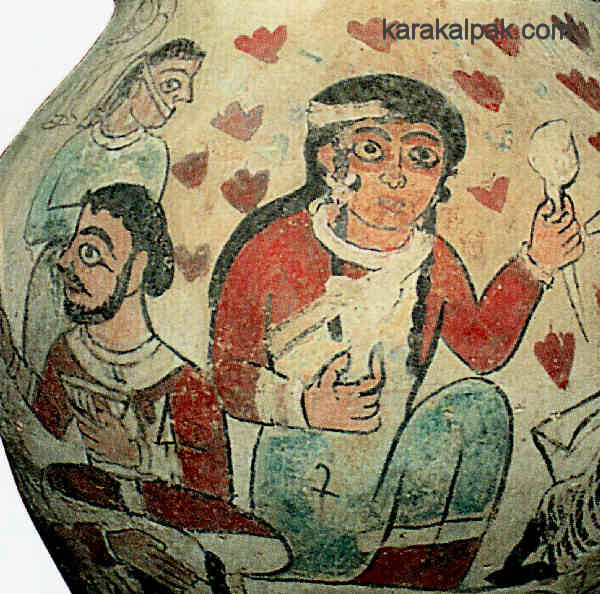

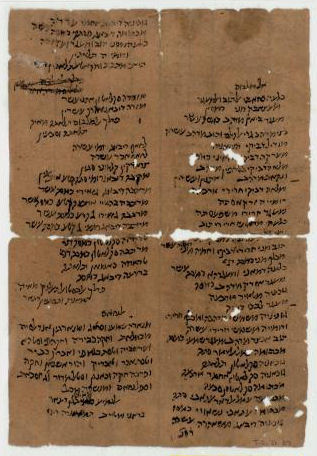

Records discovered in Egypt suggest that there were by now a whole plethora of different types of head coverings and face veils. During the last

century some 750 bridal dowry lists that were once appended to marriage contracts were restored from fragments discovered in the geniza

or storeroom of the Ben Ezra synagogue in Fustat (Old Cairo) and the cemetery of Basatin. They have provided us with a rich source of information

on the costume of Jewish newly wed brides, and by inference, Egyptian middle-class women in general.

|

They mainly date from the Egyptian Fatimid (909-1171) and Ayyubid (1171-1250) periods. More than half of the names of the items of costume listed

relate to veils and head coverings. Admittedly the majority are face veils, the most common being:

|

Fortunately from the 13th century onwards we finally gain access to manuscripts produced in Iran and Iraq with miniature paintings that depict

some of the garments listed above, although the terms used to describe them are never given. However this was a crucial time when the whole region

was thrown into chaos by the Mongol conquest. Before viewing some of these images we first need to consider the impact of Mongol rule on costume

and culture.

Chinggis Khan overwhelmed Mawaran-nahr and Khorezm in 1221, leaving their governance after his death to Chaghatay and Jochi's son Batu

respectively. Later, in 1258, Chinggis's grandson Hulägu gained overall control of northern Iran and Iraq , although the emerging power of the

Mamluks in Egypt prevented him from securing Syria.

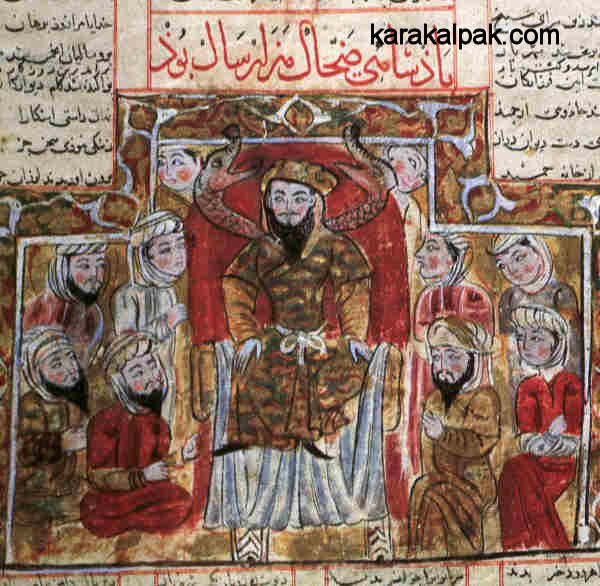

As we have already shown in our work on the sa'wkele, female headdresses at the nomadic Mongol court of

the Khanate of Qipchaq on the Volga were very different from anything previously seen in the court of the caliphate. Mongol aristocratic married

women never veiled themselves, although they did completely conceal their hair under the boghtaq headdress. In 1253-55 William of Rubruck

observed that on the day after a woman was married she shaved off her hair from the middle of her head to her forehead. She gathered the rest of

her hair in a knot and stuffed it into the top of the bogtagh. Ibn Batutta witnessed the same headdresses in 1334 at Sultan Őzbeg's court,

also on the Volga.

The court of the Golden Horde maintained its Mongol heritage for over a century by isolating itself from the surrounding sedentary centres.

Yet in the cities and wider steppes of Central Asia the indigenous populations retained their pre-Mongol traditions. Thus when ibn Batutta

journeyed from the Volga to Khorezm, in the eastern part of the Khanate of Qipchaq, he encountered the Amir Qutlugh Timur's wife in the open

wearing not a boghtaq but a veil across her head. It is likely that the women of Khorezm were influenced not by Mongol but by

neighbouring Khurasan fashions, although the Mongols did introduce Chinese textiles and Chinese motifs.

Our one insight into Central Asian female costume at this time is provided by Li Chih-chang, the follower of an elderly Taoist monk K'iu Ch'ang

Ch'un, who travelled from China to Samarkand in 1221 accompanied by 18 other disciples following an invitation to meet Chinggis Khan. Li Chih-chang

observed that both the men and women of Ho chung (Samarkand) braided their hair. High-status women enveloped their heads with a black or

dark red gauze, five to six feet long, frequently embroidered. Ordinary women covered their heads with linen [probably cotton] and other stuff,

"and thus bear some resemblance to our [Buddhist] nuns."

Over time the Mongol aristocracy that remained in Central Asia became inevitably assimilated into local Turkic culture, adopting Islam along the way.

Although Ruy Gonzÿlez de Clavijo witnessed the Great Khanum wearing a headdress of ridiculously large proportions clearly modelled on the

Mongol bogtagh when he visited Timur in Samarkand in 1403, it is likely that this was no more than a piece of theatre designed to reinforce

Timur's claims of Chinggisid decent. This would not have been an item of costume worn by the wealthy women of Samarkand.

Likewise the Mongol Il-Khanate of Iran ruled from a nomadic court, upholding Mongol law and customs. Fourteenth century illustrations show that the

boghtaq was worn extensively by aristocratic Mongol women. We know for example that Arghun Khan (1284-91) signalled his acceptance of

Tudai Qatun as his wife by placing a boghtaq on her head. However over time the aristocracy of the Il-Khanate were converted to Islam

and encouraged to adopt traditional Persian ways, sometimes leading to internal tensions. In fact Persian urban culture rebounded quickly after

the initial Mongol destruction, enjoying a strong revival and in some cases adopting imported East Asian themes. The subsequent conversion of the

Mongol hierarchy to Islam led to a renewed commitment to traditional Persian religion and culture.

In the field of fashion Hermann Goetz believed that 13th century Iranian women's costumes and head veils remained essentially unchanged from

pre-Mongol times, except that more parts of the body were covered using more garments, including an all-enveloping cloak. One feature of the

period was that the headscarf was closely drawn about the chin and the shoulders.

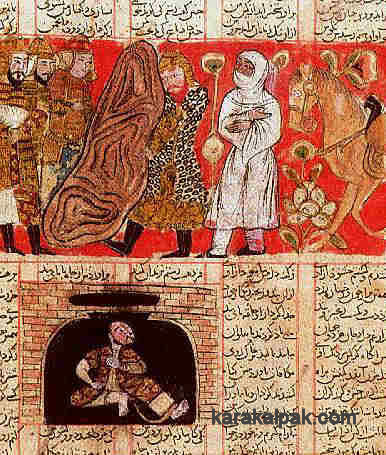

One of the earliest illustrations of female face veils shows a row of wealthy women, in the gallery of a mosque, wearing niqab and

miqna'a-like garments, with their colourful cloaks pulled over their heads and wrapped tightly around them:

|

Another early illustration referred to by Jennifer Scarce is from a mid-13th century miniature showing scenes of daily court life, with men and

women wearing both indoor and outdoor dress. Inside the court the women wear their hair in four or more long thick plaits, their hair uncovered

apart from striped or plain round-topped head wrappers. Outdoor pictures show the women covered in cloaks with brightly coloured shawls wrapped

around the top of their heads and then drawn over their lower face to be tucked in at the side, leaving only an opening for the eyes:

|

Scarce also refers to a 13th century illustration from al-Tabari's Annals of the Apostles and Kings, showing three women wearing white,

khimar- or bukhnuq-like cloaks, worn over a white veil extending from nose to chin. They cover the head and wrap tightly

around the face, falling over the shoulders and arms.

An early 14th century miniature from Tabriz in northern Iran shows fine details of a number of similar khimar-like head veils, made from

long rectangular scarves with decorated or fringed ends. One end is pulled across the breast, wound tightly around the head, crossed again under

the chin and then folded over the head so that the other end hangs over the shoulder like a cape. The result is remarkably similar in appearance

to a modern kimeshek, although it is not of course a tailored garment:

|

Another illustration from the same period, this time from Shiraz in the southwest, shows the same garment, although in this instance modelled by

a man!

|

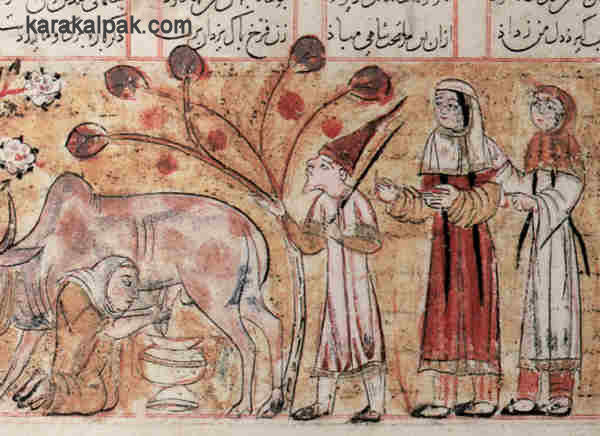

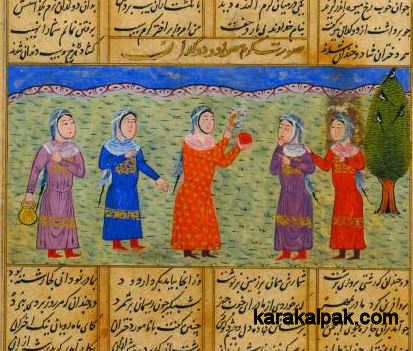

This style of headdress seems to have been particularly popular in Iran in the 14th century. A second example from Shiraz shows two women wearing

headscarves with a decorative border, although the milkmaid wears just a plain white one:

|

A third example shows a woman in public with the headscarf wound so that it covers not only the sides of the face but also the mouth and chin:

|

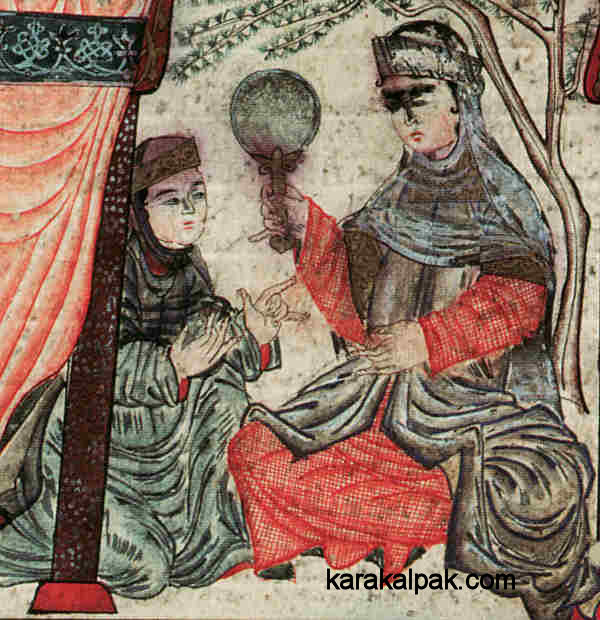

A popular style of khimar during the first half of the 14th century involved the use of a translucent shawl, revealing the hair, neck,

and upper bosom. Such head veils were only used inside the home. A miniature from Tabriz shows three khimar-like veils made from transparent

gauze, so thin that the women's plaited hairstyles and necklines of their coats can be plainly seen. Of course this is a domestic scene with

no need for public veiling. It depicts Sindukht, the queen of Kabul, with her hand raised in reproach against her kneeling daughter, Rudaba.

The maid stands at the back, dressed in black.

|

A slightly earlier example, also from Tabriz, clearly shows one edge of the head veil hanging down from the head and falling over the part that is

stretched across the breast. Both head veils are surmounted by frontal headbands:

|

The transparent head veil seems to have maintained its popularity into the 15th century, as this miniature from the controversial Jules Mohl copy

of the Shahnama shows:

|

Our final 14th century illustration shows a different wimple-like style of head veiling, with just a short scarf wrapped under the chin,

surmounted with a turban-like head wrapper.

|

During the Timurid period a new feature emerged around the middle of the 15th century – the head veil became secured by a type of bandeau tied

around the forehead, with the ends tied behind the head and left hanging loose down to the neck:

|

Later the veil became shorter, covering only the top half of the back of the head, held in place by a double bandeau. As the century progressed

the head veil slowly went out of fashion, women preferring to go bare-headed, at least indoors.

Interestingly most of the paintings we have seen so far show women with their heads covered but their faces unveiled. It seems that in Mamluk Egypt

the face veil was more common. During the reign of Sultan Ibn Qalawun in the early part of the Mamluk period, 1250-1517, veiling the head, face, and

body was a symbol of status and respectability for all upper and middle class urban women. The niqab, miqna'a and qina' were

essential items of dress and even commoners wore the niqab and burqu'. Costumes for the elite were lavish and high-status women

wore the finest veils. According to Leo Mayer the sight of a woman in public without a face veil was seen as a sign of great distress. He

classified face veils into three types: a black net covering the face, the same but with holes for the eyes, and a white or black veil covering

the lower face up to the eyes.

Three 14th/15th century Mamluk veils have been excavated from the Red Sea port of Quseir al-Qadim and the Nile site of Qasr Ibrim in southern Egypt.

One resembles the burqu', consisting of a headband and a lower face veil suspended so as to leave openings for the eyes and a ridge over

the nose.

We can conclude that the khimar-like head veil, along with many other related garments, seems to have been remarkably common and widespread

in Iran, Iraq, and Egypt for a quarter of a millennium up to the end of the 15th century. Changing fashions have meant that the style of wearing the

head veil, and the textiles used for it, have progressively evolved, but the basic structure and overall appearance has remained the same.

References

Al-Muqaddasi, The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions, translated by B. A. Collins, Centre for Muslim Contribution to Civilization and

Garnet Publishing, Reading, 1994.

Baer, E., The Human Figure in Early Islamic Art: Some Preliminary Remarks, Murqamas, Volume XVI, pages 32 to 41, E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1999.

Baker, P. L., Islamic Textiles, British Museum Press, London, 1995.

Battutah, ibn, The Travels of ibn Battutah, The Hakluyt Society, London, 1958-2000.

Blaramberg, I. F., Recollections [in Russian], Science, Moscow,1978.

Brosius, M., Women in Ancient Persia, 559-331 BC, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1996.

Ch'ang Ch'un, K., Si Yu Ki: Travels to the West of K'iu Ch'ang Ch'un, Medieval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources, Volume 1, translated

by E. Bretschneider, page 89, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd., London, 1887.

Clavijo, R. G. de, Embassy to Tamerlane 1403-1406, translated from the Spanish by Guy Le Strange, George Routledge & Sons, Ltd., London, 1928.

Curtis, V. S., The Parthian Costume and Headdress, The Arsacid Empire: Sources and Documentation, Beiträge des Internationalen Colloquiums,

Eutin, 27-30 June, 1996, pages 61 to 73, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, 1998.

Dawson, C., The Mongol Mission, Sheed and Ward, London, 1955.

Dawson, T., Propriety, Practicality and Pleasure: the Parameters of Women's Dress in Byzantium, A.D. 1000-1200, Byzantine Women: Varieties of

Experience 800-1200, edited by L. Garland, pages 41 to 76, Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot, 2006.

El Guindi, F., Veil: Modesty, Privacy and Resistance, Berg Publishers, Oxford, 1999.

Fitzgerald, E., translator, Rubâiyât of Omar Khayyâm and Persian Miniatures, Productions Liber, Friberg, 1979.

Fowden, G., Qasayr 'Amra: Art and the Umayyad Elite in Late Antique Syria, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2004.

Galerkina, O., Mawarannahr Book Painting, Aurora Art Publishers, Leningrad, 1980.

Goetz, H., The History of Persian Costume, Chapter 53, A Survey of Persian Art from Prehistoric Time to the Present, Volume VB, edited by A. U.

Pope and P. Ackerman, Sopa, Ashiya, Japan, 1981.

Goitein, S. D., A Mediterranean Society, The Jewish Communities of the World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza, Volume IV: Daily Life,

University of California Press, Los Angeles, 1993.

Hillenbrand, R., The Arts of the Book in Ilkhanid Iran, The Legacy of Genghis Khan, Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353, edited by

L. Komaroff and S. Carboni, pages 134 to 167, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2002.

Houston, M. G., Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian and Persian Costume, Dover Publications, New York, 2002.

Kaizer, T., The Religious Life of Palmyra, A Study of the Social Patterns of Worship in the Roman Period, Franz Steiner Velag, Stuttgart, 2002.

Kubičková, V., Persian Miniatures, translated by R. Finlayson-Samsour, Spring Books, London, 1961.

Lillys, W., Reiff, R., and Esin, E., Oriental Miniatures: Persian, Indian, Turkish, Souvenir Press, London, 1965.

Llewellyn-Jones, L., Aphrodite's Tortoise: The Veiled Woman of Ancient Greece. The Classical Press of Wales, Swansea, 2003.

Mayer, L. A., Mamluk Costume: A Survey, Albert Kundig, Geneva, 1952.

Nashat, G., and Tucker, J. E., Women in the Middle East and North Africa: Restoring Women to History, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1999.

Nashat, G., and Beck, L., Women in Iran from the Rise of Islam to 1800, University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 2003.

Oiszowy-Schlanger, J., Karaite Marriage Documents from Cairo Geniza: Legal Tradition and Community Life in Medieval Egypt and Palestine,

E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1997.

Pletneva, S. A., Polovets Rock Sculptures [in Russian], Academy of Science of the USSR, Moscow, 1974.

Pletneva, S. A., Polovsy [in Russian], Academy of Science of the USSR, Moscow, 1990.

Rakhimova, Z. I., Central Asian Women's Costume in the Miniatures of Maveranna from the 16th to 17th Centuries, Culture of the Middle East [in Russian],

pages 135 to 157, FAN, Tashkent, 1990..

Stillman, Y. K., The Importance of the Cairo Geniza Manuscripts for the History of Medieval Attire, International Journal of Middle East Studies,

Volume 7, Number 4, pages 579 to 589, October 1976.

Stillman, Y. K., Costume as Cultural Statement: The Esthetics, Economics, and Politics of Islamic Dress, The Jews of Medieval Islam, edited by

D. Frank, pages 127 to 144, E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1995.

Stillman, Y. K., Arab Dress: A Short History from the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times, E. J. Brill, Leiden, 2003.

Titley, N. M., Persian Miniature Painting, The British Library, London, 1983.

Tolstov, S. P., Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographical Expedition, Academy of Science of the USSR (1945 – 1948) [in Russian], pages 7 to 46,

The Works of the Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographic Expedition 1945 -1948, Volume 1, edited by S. P. Tolstov and T. A. Zhdanko,

Academy of Science of the USSR, Moscow, 1952.

Van der Toorn, K., Family Religion in Babylonia, Syria and Israel, Continuity and Change in the Forms of Religious Life, E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1996.

van Lohuizen-Mulder, M., Frescos in the Muslim residence of Qusayr 'Amra, Bulletin Antieke Beschaving, Issue 73, 1998.

van Loon, M. N., Anatolia in the Second Millennium BC, E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1985.

Winter, B. W., Roman Wives, Roman Widows, The Appearance of New Women and the Pauline Communities, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company,

Grand Rapids, 2003.

Yatsenko, S A, Late Sogdian Costume, Eran ud Aneran, Transoxiana, Universidad del Salvador, Buenos Aires, 2003.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

|

This page was first published on 7 March 2008. It was last updated on 6 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |