The Karakalpak Kiymeshek - Part 3

|

The Karakalpak Kiymeshek - Part 3

|

|

ContentsPart 1SummaryThe Karakalpak Kiymeshek Role of the Kiymeshek The Aq Kiymeshek The Qızıl Kiymeshek Part 2Different Qızıl Kiymeshek PatternsDistribution of Qızıl Kiymeshek Patterns The Dating of Qızıl Kiymesheks Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms References Part 3Other Kimeshek-Like GarmentsThe Qazaq Kimeshek The Uzbek Lyachek The Tajik Lachek and Kuluta The Turkmen Esgi, Lechek and Chember The Kyrgyz Elechek and Ileki The Khimar and Similar Islamic Veils References Part 4Previous Ideas on Kimeshek OriginsA Short History of Veiling up to the 16th Century References Part 5The History of the KimeshekWhere to see Karakalpak Kiymesheks References Other Kimeshek-Like GarmentsKiymesheks are not unique to the Karakalpaks. Many other ethnic groups in Central Asia, especially those belonging to the Qipchaq-speaking Turks, wore similar or related garments. Looking more widely one can find head veils of similar appearance throughout the Islamic world from Kurdistan to Oman and from North Africa to Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Northern India. However nothing can match the Karakalpak kiymeshek for its visually stunning appearance.

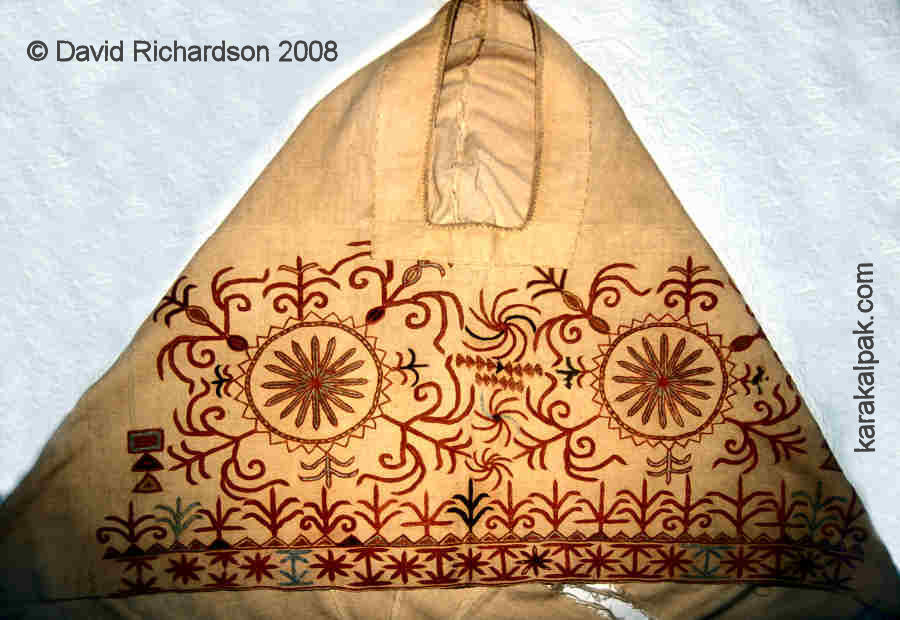

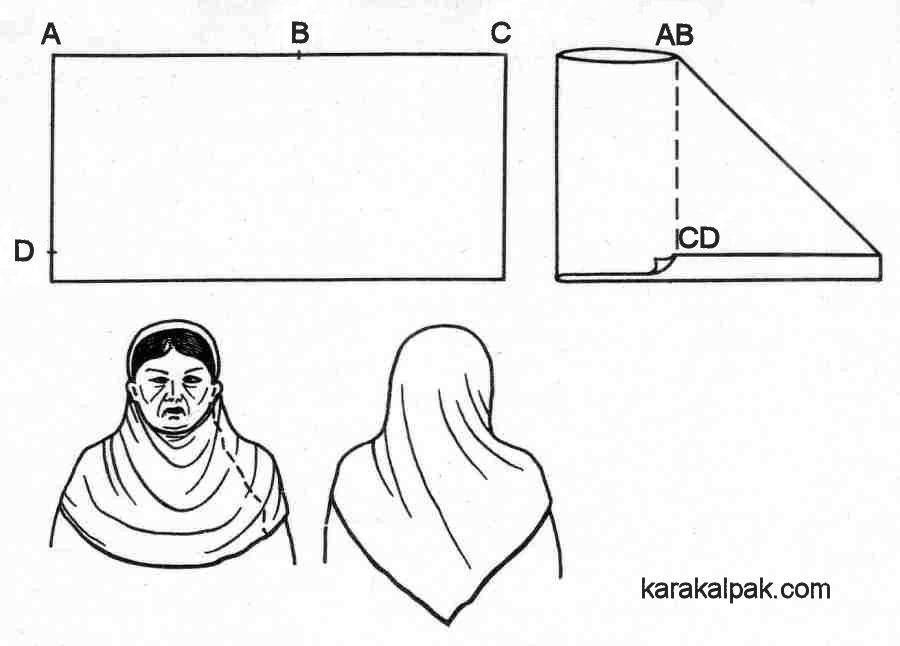

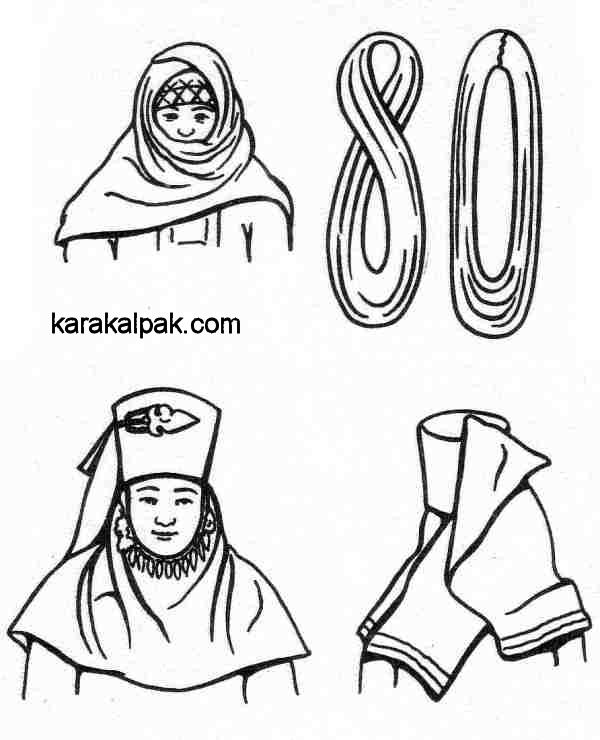

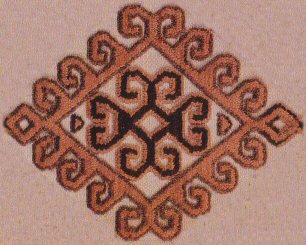

Illustration of a Qazaq kimeshek from Semipalatinsk.

|

|

There is no equivalent to the kiymeshek in the costumes of the other peoples of the Volga region. Among the Bashkirs married

women traditionally wore a kashmau cap and plait cover and a dulbega breast cover, but in the early 20th century adopted

a head veil composed of two large red shawls. Chuvash married women wore an equivalent khushpu cap, which also gave way to a

headdress composed of shawls and kerchiefs.

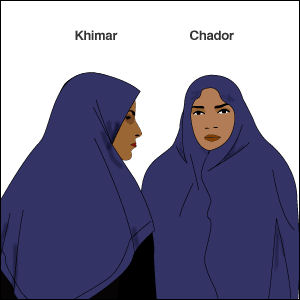

Throughout the Middle East, North and East Africa, and Europe, Muslim women continue to wear another garment very similar to the

kiymeshek in appearance although not in structure. Known as the khimar it is a headscarf that is draped so that it

completely covers the hair, extends down over the chest to conceal the breasts, but leaves the face exposed. For greater privacy some

women also wear a separate niqab underneath the khimar which veils the nose and mouth but not the eyes.

The chador, worn by Iranian women outside the home, is somewhat similar but extends down to the shoes. There are many other

similar garments that cover the hair but not the face, worn in various styles in different regions of the Islamic world.

There is a clear geographic separation between the khimar, kimeshek, and lyachek. The khimar is found in the

Middle East from Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the Yemen to Syria, Iraq, and Iran. The kimeshek occurs in the north and western edges

of Central Asia – Kazakhstan, Khorezm, and the southern Volga. The lyachek occurs in the south and eastern parts of Central Asia –

Iran, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and northern India.

The study of these other related garments is important in throwing light on the origin and development of this particular category of headwear.

The Qazaq Kimeshek

Just like the Karakalpaks the Qazaqs believed that a girl had to conceal her hair at the time of her marriage. The headdress of a married

woman consisted of an under cover that concealed all but the face, and an upper turban. According to Zakharova and Khodzhaeva the use of a

kimeshek as the under cover was geographically widespread among the Qazaqs, apart from in the Ural and Turgay regions where women

placed a folded kerchief over the head, crossing the ends over the breast or throwing them over the arms. From the beginning of the 19th century

all of these garments were only made from white cloth, although pale blues, pinks, and beiges became popular in the 20th century. However,

according to 18th century observers, the Qazaqs were using brightly coloured striped textiles.

|

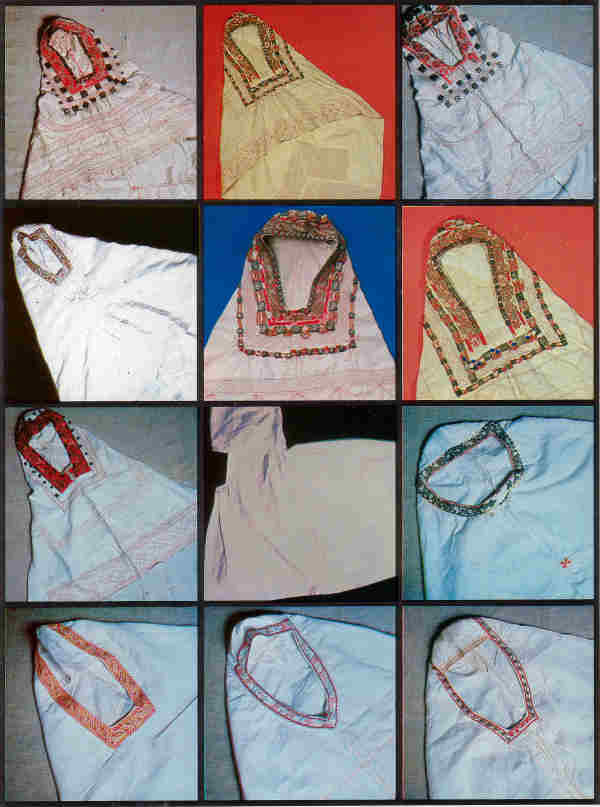

The Qazaq kimeshek has a similar structure to the Karakalpak kiymeshek, with a hood covering the hair, breast, and upper

arms containing a small aperture at the front for revealing the face, and with a tapered tail or quyriq hanging down at the back.

However in the case of the Qazaqs there were a wide variety of kimeshek types, according to the nature of the cut, the shape of

the front of the hood, the length and form of the tail, and the type of decoration.

|

|

Zakharova and Khodzhaeva identify six different categories of Qazaq kimeshek:

|

The most elegant kimesheks occurred among the young Qazaq women of Semirechye, with a broad band of coloured silk or gold embroidery

framing the face along with corals, beads, and silver platelets. In a few cases the bottom edge of the breast cover was edged with simple

embroidery. The Kyzai clan of the Nayman in Jungaria were renowned for their bright and complex embroidery patterns around the face opening

and breast part of their kimesheks. The embroidery of kimesheks in North and Central Kazakhstan was much simpler and

incorporated corals, beads, and silver. In South Kazakhstan and in Mangishlaq they embellished the embroidery with patterned braid or strips

of bright cloth, sewed silver to the seams of the breast part, and decorated the edges of the front and tail with a fringe.

|

Lyushkevich studied the Qazaq population living in the region surrounding the Bukharan oasis. Women were married wearing a shawl as a head veil.

However after the birth of the first child women put on a kimeshek, which was worn with a sharshi turban. The kimeshek

was traditionally made from white cloth, but in the mid-20th century was manufactured from a length of gauze about 1½ metres long.

|

The kimeshek was worn with the seam on the left, with a semicircle of cloth covering the breast. The design was unique to this region,

although there was some similarity to the kimeshek worn in southern Kazakhstan.

Surprisingly the kimesheks of the Qazaqs living alongside the Karakalpaks in the lower Amu Darya were also plain white and

rarely decorated with embroidery, in contrast to the colourful kiymesheks of their neighbours.

|

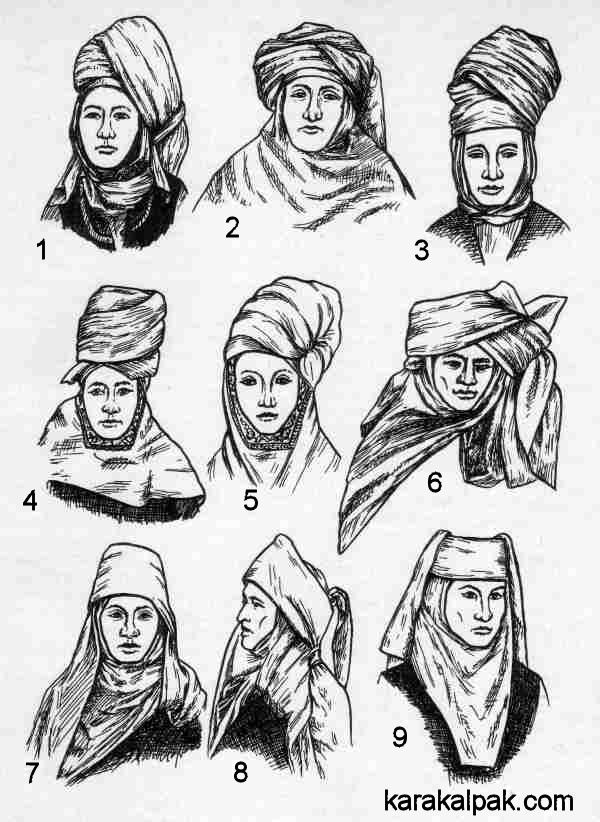

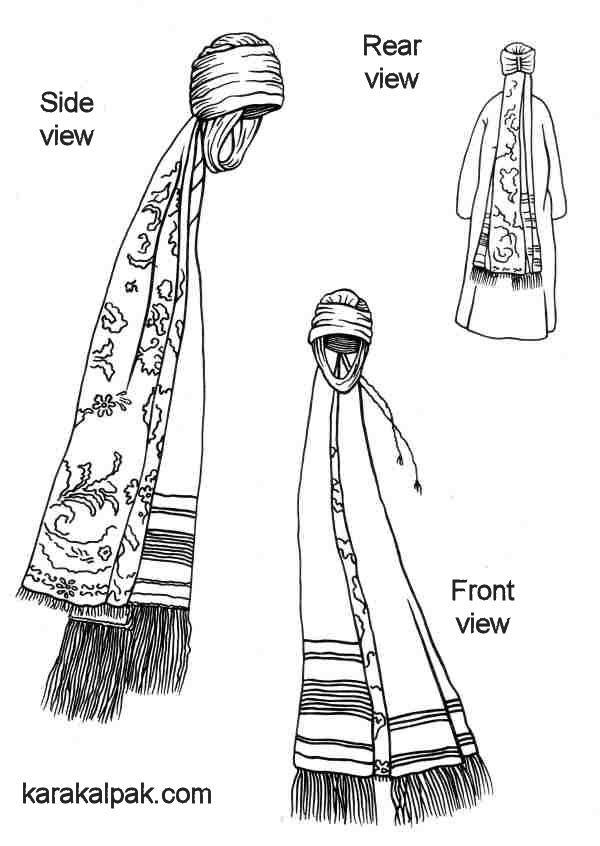

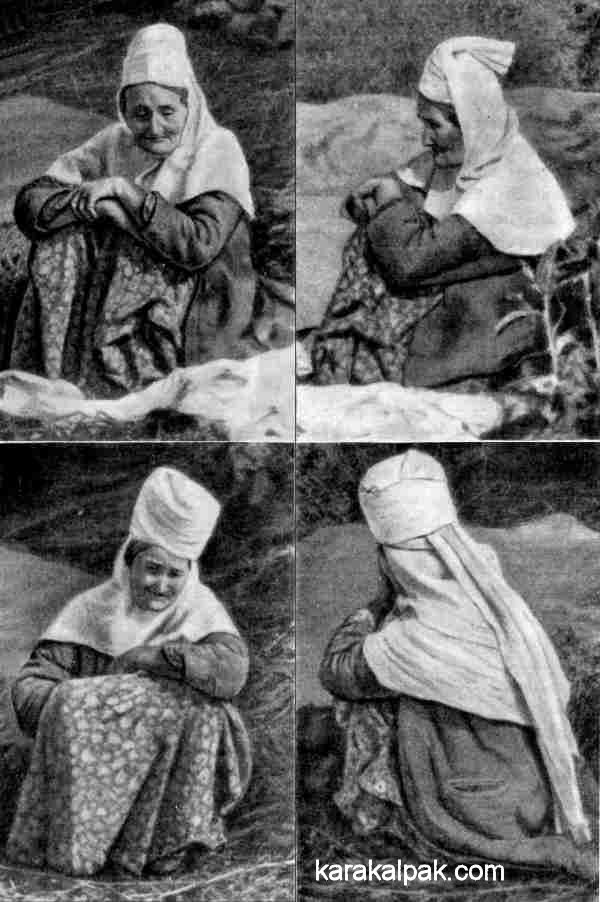

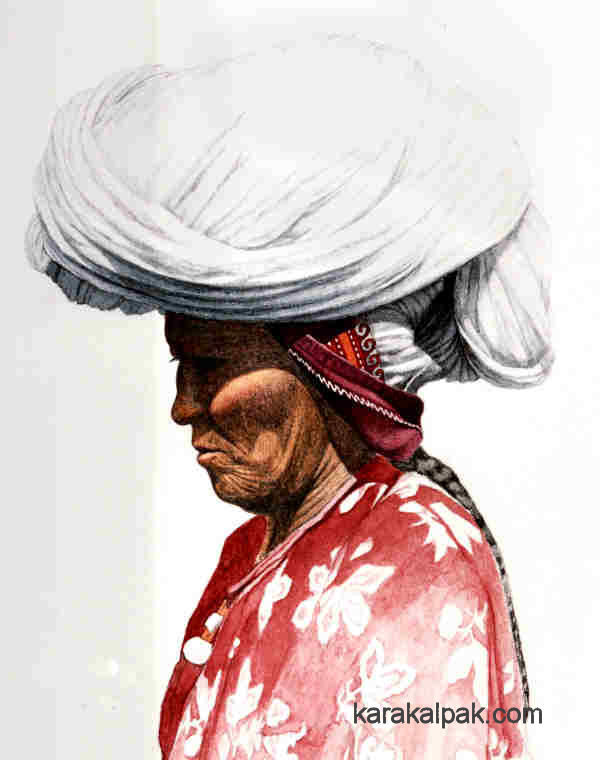

As with the Karakalpaks the Qazaq kimeshek was always worn with a turban, made from a large piece of white cloth, often two metres

square and folded diagonally into a long strip. This turban was generally referred to as a jaulıq, or üstingi

(upper) jaulıq, since the term jaulıq once applied to the entire complex of a married woman's headwear. However

there were also regional terms. In South, Central, and Eastern Kazakhstan the turban was frequently called a sharshı, literally

a square. In Semirechye, the Altai and Xingjian it was called a shılawısh, and in South and Central Kazakhstan a

kündik.

The use of the kimeshek seems to have lasted longer among the Qazaqs than among the Karakalpaks, especially in rural areas.

When ethnographers interviewed elderly Qazaqs in the 1950s they discovered that the kimeshek began to go out of use in the 1930s

in some of the northern and eastern regions but continued to be worn by the elderly. The turban had universally fallen out of use by the 1950s.

|

However in the lower Amu Darya its use has continued among a minority of the elderly until the present day. In the mid-1960s, Shalekenov

noted that only old Qazaq women were still wearing the kimeshek in combination with a white cotton turban which they called a

jaulıq.

The Uzbek Lyachek

The Uzbeks also wore an under cover, that concealed all but the face, and an upper turban, the former being known as a lyachek, lachek,

lyachak or lachak, spellings varying widely throughout the literature. Sukhareva has suggested the name might derive from

lokicha, the diminutive of loki, the turban-like head cover once worn in Samarkand and Tashkent.

|

According to Sukhareva the lyachek or lachak of the Uzbeks of Samarkand and Nurata was merely a rectangle of muslin cloth

wrapped over a kulutapushak cap and under the chin, tightly covering the cheeks and concealing the hair and the chest. Over the

top of the cap they wound a turban or salla. In Kashkadarya and Tashkent the lyachek was not only larger, the free ends

falling down to the back and the breast, but it had an elongated hole for the face. Sukhareva interviewed old women in the 1930s and 1940s

who confirmed that the lyachek was worn for formal occasions such as a wedding or other ritual meetings. It was worn either at the

time of marriage, as in Nurata, or soon after the wedding, as in Bukhara. In Urgut an especially large lyachek was worn with a

turban as a sign of piety by the wives of ishans.

Pisarchik discovered that the Tajiks of Nurata wore a laychak that was very similar to the Uzbek lyachek, also made from a

rectangle of cloth and worn with a long salla turban. It was first worn by the new bride at the time of her wedding, just before

she was presented to the wedding guests.

The costume of the Uzbeks of Khorezm was studied in detail by researchers working for the Khorezm Archaeological and Ethnographical Expedition

during field studies conducted between 1946 and 1953. M. V. Sazonova led the team investigating the Uzbeks living in the southern part of the

Khorezm region (not the viloyat), while K. I. Zadykhina led the team in the north.

For the Uzbeks of southern Khorezm (the region around Hazarasp and Khiva), the lyachek was something quite different - not a single

garment but an assembled headdress worn on a major female holiday known as the lache-toy. Sazonova has described this for a married

woman in the 20 to 24-age bracket who only donned the assemblage after the birth of her first or second child. It began with a quilted cotton

takh'i fastened under the chin with laces and a long cotton shawl, or tey rumal, wrapped around the takh'i with one

end hanging free at the back. A domakcha or white band with small folds went under the chin with its two ends pinned to the

takh'i by needles. The head was wrapped with a folded red and gold turma, its ends left hanging freely down the back, and

an embroidered Bukharan alaka plait cover (similar to that used on the back of the Karakalpak sa'wkele) was suspended

over it. A cotton pad was placed on top to increase the height and the sides were wrapped with a folded strip of silk cloth fastened at

the back. Amuletic owl feathers were pinned to the sides as a final embellishment.

|

Once a woman reached the age of 50 or 55 she wore a more conservative lyachek composed of from three to five white shawls, each

from 2 to 3½ metres long. Instead of a red tu'rme they used a white tu'rme with blue or green stripes. Different

regions of the Khorezm oasis had different ways of twisting and tying the shawls. During the winter the outer shawl was normally woollen.

|

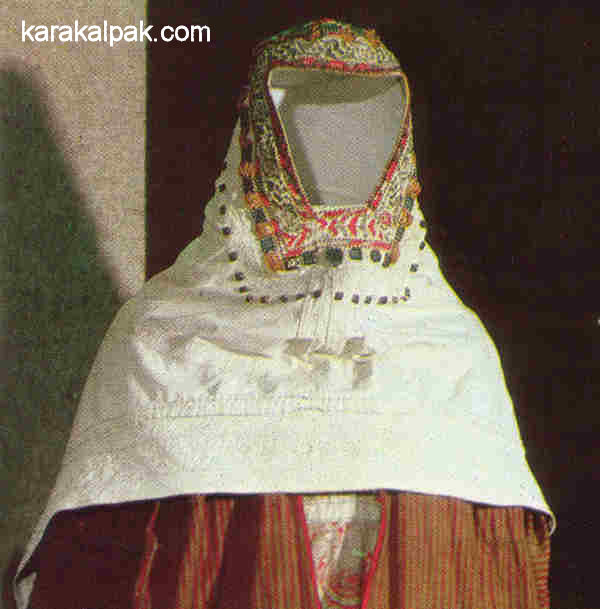

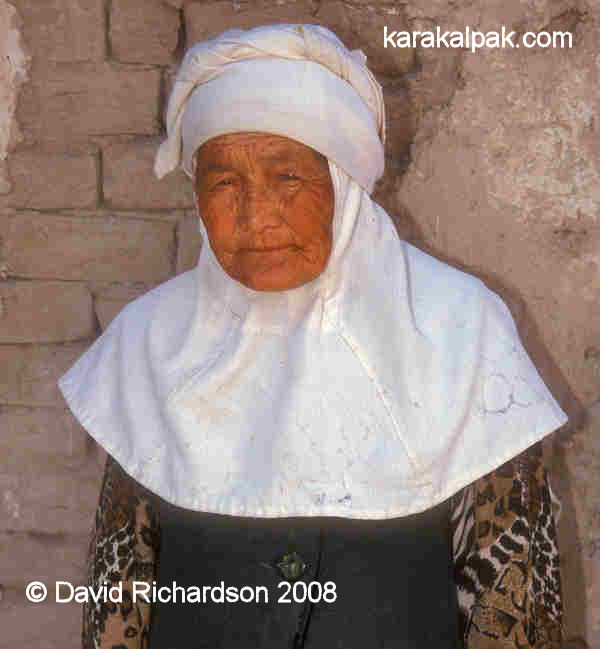

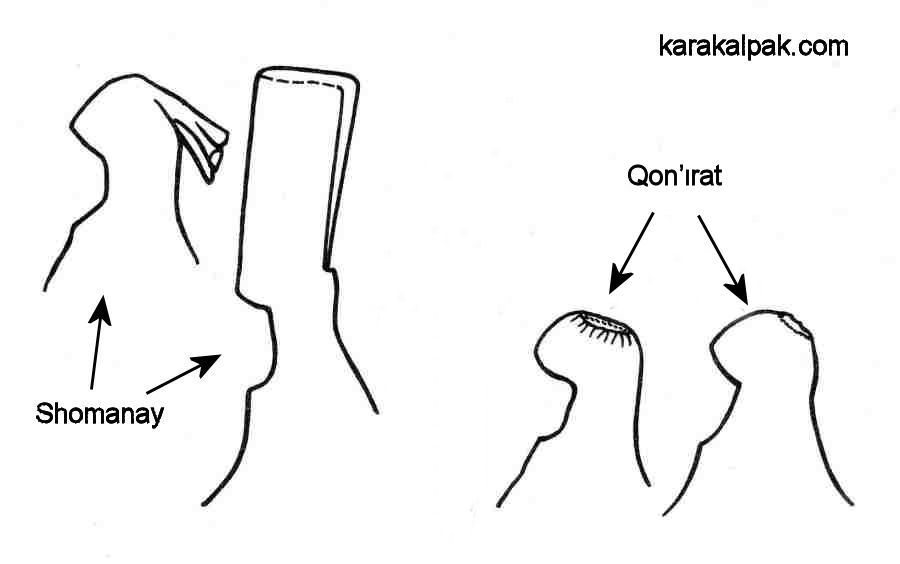

The Uzbeks of northern Khorezm (including those living in Karakalpakstan) had completely different traditions. Zadykina found that in the

early 1950s only very old women over the age of 70 were still wearing a tailored lyachek, although in earlier years they had been

worn by 55 to 60-year-olds. Made from white cotton it was somewhat similar to an undecorated Karakalpak aq kiymeshek, having a

triangular front or tamakhsa with a face opening and a diamond-shaped tail or khalaka. The top was either open or partially

tightened with stitching. The lyachek tightly covered the head and concealed the upper arms and breast. A 5-metre-long white

turban, known as a bash orau, covered the top of the head. The method of tying the bash orau varied according to region.

Thus in the Qon'ırat and Qipchaq regions of Karakalpakia the turban was wide and tied so that the ends were tucked into the folds,

whereas in the Ma'n'gıt and Gurlen regions further south the turban was taller with the ends projecting forward in the shape of horns.

|

By contrast younger and middle aged women were wearing the bash orau but not the lyachek. Young women wore a predominantly

red bash orau over the takh'ya, generally made from calico or from factory-made kerchiefs, although the wealthy used silk

kerchiefs or tu'rme. A folded coloured or white shawl was then draped over the top.

As a woman grew older so the size of the bash orau increased. A 35-year-old would wear a bash orau made from a 3-metre

long shawl or from three factory-made kerchiefs. For a festival she might add a silk tu'rme. By the age of 40 or 45, following

the marriage of the eldest son, a woman ceased to wear the coloured bash orau, choosing a white bash orau instead, in some

cases with a shawl draped over the head and back.

One other feature of the northern region was that many women also wore the jegde over the bash orau. It was clear to the

two authors that the northern and southern Uzbeks of Khorezm followed completely different traditions in line with their separate historical

origins.

The Tajik Lachek and Kuluta

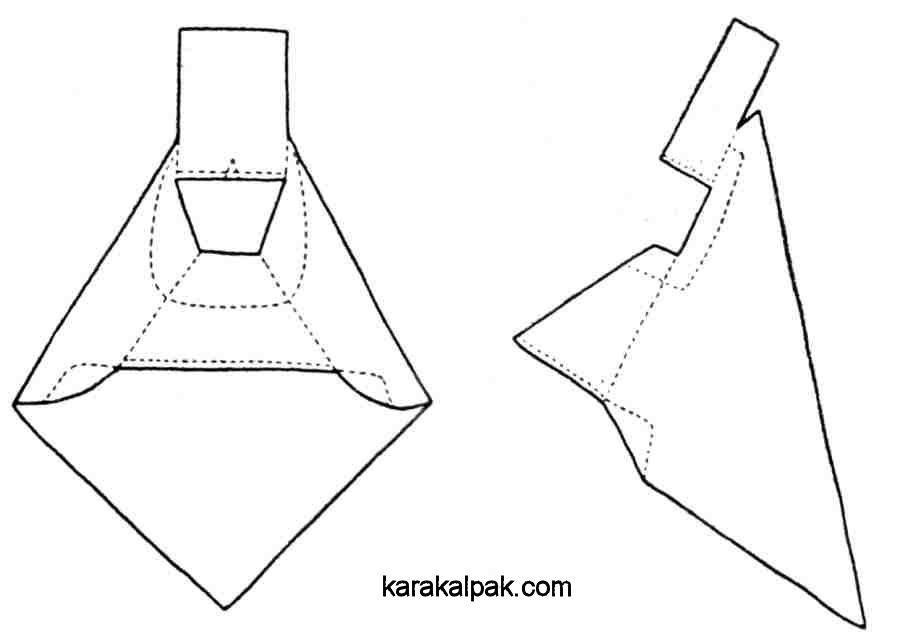

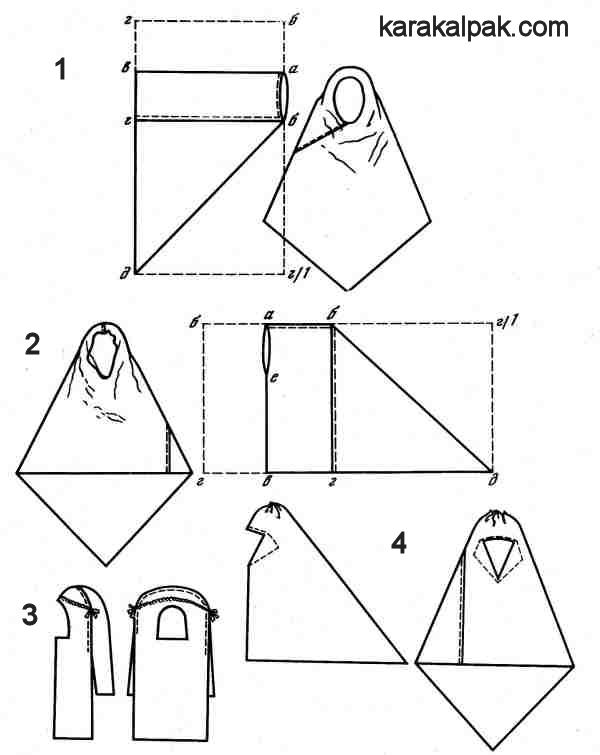

In about 1980 Shirokova investigated the costumes of the Tajiks of northern Tajikistan living just over the border from Uzbekistan. She

discovered that in certain regions old women had once worn a lyachek-type garment known as a lachek or a kuluta.

It was made from white cloth and was worn during the 19th and early part of the 20th century. In the village of Gusar in the upper Zeravshan

valley, not far from Pandjikent, the women had once made a lachek from a length of white material about 1½ metres long. After

folding one of the short ends over by 27cm, the second opposite short end was folded over along a diagonal to meet it. The ends of the two

folds were then sewn together, the opening at the end of the first fold (a - b on diagram 1 below) apparently forming the face opening:

|

The lachek was worn over a skullcap with a plait cover, known as a kuluta. A chakaband kerchief was wrapped around

the head to create a frontal bandage and a large square white shawl or kars was folded diagonally and thrown over the top.

Old women in the northern towns of Ura-Tube (near Khodjend) and Kanibadam (near Kokand) claimed that their great-grandmothers wore a

kuluta, also made from white cloth. In Ura-Tube this was made from a rectangle of cloth, 142cm by 77cm. As before one of the

short sides was folded over by 32cm and the other short side was folded over diagonally to meet it. In this case, however, the opening for

the face was cut in one end of the first fold - see diagram 2 above. The kuluta was worn with a 3 or 4-metre long white turban

known as a loki.

Meanwhile in Kanibadam the kuluta was quite different, made from two rectangles of white cloth, the front longer than the rear

(79cm compared to 57cm). The two narrow matching sides were cut to create rounded ends, which were then sewn together to create the hood.

See diagram 3 above. A face opening was then cut in the longest side and a wide cord wound from red, yellow and blue tapes sewn across the

forehead. It was worn with a large shawl over the top.

Shirokova discovered a fourth type of garment, another kuluta, still being worn in the village of Kul'kent near to Isfare. Shaped

like a narrow Karakalpak aq kiymeshek, it had a v-shaped face opening and a gathered top. See diagram 4 above. It was worn over a

velvet kulokh cap and was covered above with a large, white, diagonally folded shawl, with the ends crossed under the chin and then

thrown over the shoulder. Finally a small folded kerchief was wrapped around the forehead.

Lyushkevich noted that the Tajiks living in the Bukhara region wore a headdress similar to the lyachek of the neighbouring Uzbeks.

He referred to it as the Uzbek-Tajik lachak-kimeshek.

|

The same style of headdress was worn by the neighbouring Karakalpaks of the Ka'nimex region and the Turkmen of the Karakul and Alat regions.

The Turkmen Esgi, Lechek, and Chember

It is not widely known that many Turkmen groups traditionally wore kimeshek-like garments. Some were described by Anna Morozova in 1989.

In particular a number of smaller tribes in the northern regions of the middle Amu Darya, such as the Eski, Sayat, and Sakar, wore the white

lechek

Other groups such as the Saryk wore the esgi, a kimeshek-like garment worn with a dastar shawl or turban. Both

garments were fashioned from lengths of cloth or scarves from 1½ to 3 metres long. These tended to be red silk or half-silk for young

women, yellow cloth for middle-aged women, and white homewoven cotton for older women, although there were exceptions. Thus among the Salyr

young women wore a yellow coloured esgi and matching dastar.

|

The Ersari made their esgi from a 2-metre-long cloth, which was tailored to resemble a Qazaq kimeshek, covering the breast

and arms and falling down the back. It was topped with a soft cap that was then wound with several silk shawls.

Other Turkmen groups have probably adopted the lyachek from the surrounding Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Qazaqs. Lyushkevich mentions the

Uzbek-Turkmen population of the Karakul and Alat regions, and the Turkmen of the Romitan region, all in the vicinity of Bukhara.

The final Turkmen kimeshek-like garment is the chember which was worn by young Chodor women during holidays and festivals

in the Stavropol district, north of the Caucasus, in the early part of the 20th century. It closely resembled the Karakalpak kiymeshek,

being tailored from red silk, decorated with braid, embroidery, and appliqué, and with a rear tail falling down to the heels. It was worn

with a sa'wkele-like, red, dome-shaped cap with a fur edge and surmounted by a dastar in the form of a large triangular red

silk shawl with a golden fringe along its edges. This small Turkmen population settled in this region during the 17th century. It is

interesting that there is no evidence of a similar garment among the Chodors in the northern regions of Turkmenia during the 19th century.

However there are some similarities with the Qaragashly and Yurt Tatars living in the nearby region of Astrakhan.

The Kyrgyz Elechek and Ileki

The costume of the Kyrgyz woman during the late 19th and early 20th did not include a kimeshek- or lyachek-like garment.

However interviews conducted with Klavdia Antipina towards the end of her life revealed her understanding that, during the 18th century, both

the Kyrgyz and Qazaqs living in present-day Kyrgyzstan used a tall, leather kimechek, topped with peacock feathers. The bride wore

this during her journey from her parent's aul to the aul of the groom's parents. There are no images of such a garment but

it was apparently worn over the shökülö headdress.

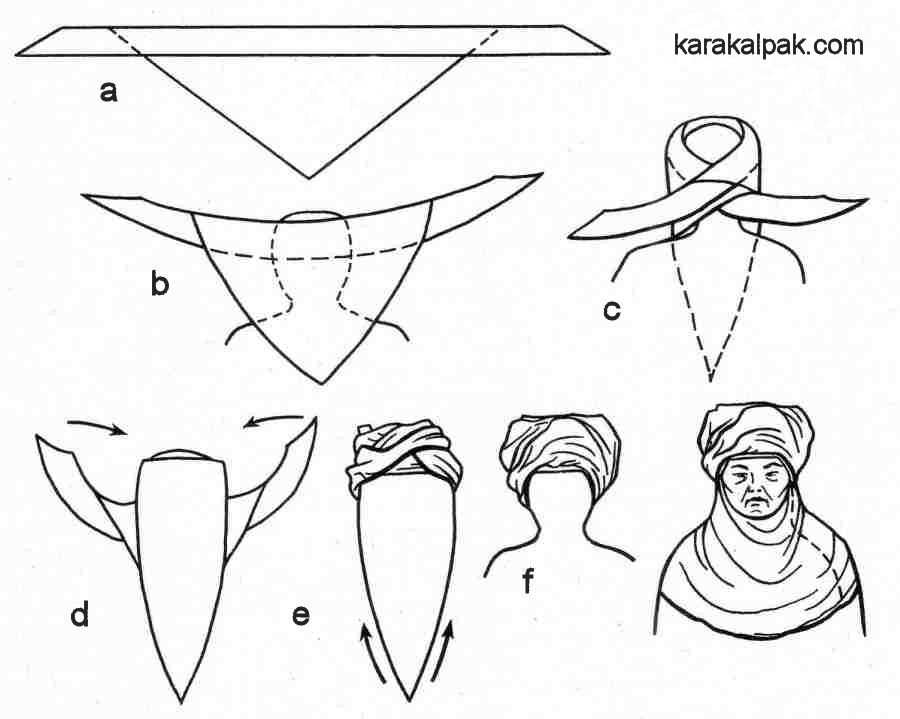

Just like the Karakalpaks it was traditional for a young woman to conceal her hair from the time of her wedding onwards. This was accomplished

by means of a wimple-like turban, known among the northern Kyrgyz as an elechek and among the southern Kyrgyz as an ileki.

The method of tying and decorating these turbans varied according to tribe or locality.

|

The elechek was made from several pieces of white cloth, at least two and generally more, some long and one square. Since the size

of the elechek was often related to wealth, the size of these cloths could reach up to 20 or 30 metres in length and together they

could weigh up to 5 kg. After a plain cap known as a bash kap or kep takıya was placed on the head, the turban was

wound around it in a parallel spiral. Sometimes a separate cloth was looped under the chin and around the cheeks to conceal the chin, neck,

upper breast, and part of the shoulders. In other cases a rectangle of cloth was suspended under the chin. The turban was held in place with

a silk or embroidered band called a kyrgak or tartma, which sometimes supported a decorative net with coloured tassels.

Additional embellishment might include a plait cover, pieces of jewellery, strings of beads or pendants, or a large white shawl, depending

on the wealth of the family.

|

The newly-wed bride first wore this enormous headdress at the time she left the aul of her parents and moved to the aul of

her future in-laws. From then on she was expected to wear it on every occasion that she left her yurt, in winter or summer, even if she was

only collecting water or pounding millet. After the birth of her second or third child the headdress was replaced by a shawl. The popularity

of the elechek began to wane during the 1930s in favour of a head shawl.

The ileki of the southern Kyrgyz was very similar to the elechek but did not conceal the chin or neck. It was worn above a

chach kep, a bonnet with a plain cotton top and an integral plait cover and earflaps, the latter parts being very finely embroidered

in maroon red and other coloured silk threads. The turban was tied so that the decorative plait cover and earflaps remained uncovered. As

with the elechek, the turban was held in place by a woven kyrgak. For a special event the ileki could be

surmounted by a decorative square known as a kalak, embroidered with floral motifs and bordered with a red silk fringe.

The Khimar and Similar Islamic Veils

Throughout the Middle East, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Northern India, North and East Africa, Malaysia, Indonesia, and lastly Europe, Muslim

women wear a plethora of head and face veils. One of these is very similar in appearance to the kimeshek and is known as the

khimar. This is a cape-like veil that completely covers the hair and extends down over the chest to conceal the breasts, leaving the face

exposed. For greater privacy some women also wear a separate half niqab underneath the khimar, which veils the nose and mouth

but not the eyes. Today the khimar is a tailored garment, frequently made of black cotton or polyester, although in the past it was

formed from a simple headscarf. The term occurs in the Qu'ran.

|

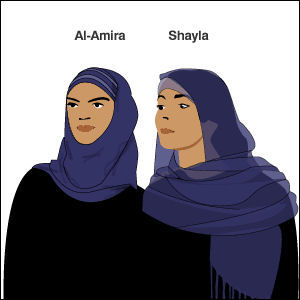

The bukhnuq or buknuk is similar to the khimar but just comes down to the bosom. It is sometimes called an Amira

hijab if it has embroidery along the edge. The chador on the other hand is longer, extending down to the feet. It is a

full length semi-circle of fabric that is thrown over the head and held closed at the front by the hands or by wrapping the ends around the

waist. It is commonly worn by Iranian women outside the house. A similar garment from Saudi Arabia is the abayah. This is an outer

sheet-like garment which covers all of the body, starting from the top of the head. The wearer drapes the abayah over the head, and

places the arms inside the arm holes. The front is normally held closed with the hands, but can be sewn closed, or buttoned.

|

The al-amira is a two-piece veil. It consists of a close-fitting cap, usually made from cotton or polyester, and an accompanying

tube-like scarf. The shayla meanwhile is a long, rectangular scarf popular in the Gulf region. It is wrapped around the head and

tucked or pinned in place at the shoulders.

The Afghan chadar or chaadar, also worn in Pakistan and parts of northern India, is a square or rectangular scarf or

shawl, folded and draped over the head to cover the hair, neck and shoulders, with one end looped over the opposite shoulder. The

chadar is not to be confused with the all-encompassing chadari or chaadaree, frequently incorrectly termed the

burqa, which is a complete garment that covers the entire face and body with only a mesh screen to see through.

References

Abdullaev, T. A., and Khasanova, S. A., Uzbek Clothing (19th to the beginning of the 20th Century) [in Russian], Fan, Tashkent, 1978.

Allworth, E. A., The Modern Uzbeks, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, 1990.

Antipina, K. I., Special Material Culture and Applied Arts of the Southern Kyrgyz [in Russian], Chapter 3 Costume and Adornments, Published

by the Academy of Sciences of the Kyrgyz SSR, Frunze, 1962.

Antipina, K. I., and Aydarbek, K., The Kyrgyzs Folk Clothes, Turk Tarih Kurumu Basimevi, Ankara, 2004.

Antipina, K. I., Traditional Kyrgyz Costume, translated and edited by Stephanie Bunn, in Kyrgyzstan, edited by P. Gribaudo, pages 21 to 64,

Skira Editore, Milan, 2006.

Galumbaeva, A., Kazakh National Clothing [in Russian], Publisher "Jalin", Alma-Ata, 1976.

Ja'nibekov, O'., Qazaq Costume, Album, O'ner, Almaty, 1996.

Joseph, S., and Naimabadi, A., Encyclopaedia of Women and Islamic Cultures, Volume 2, Family, Law and Politics, Brill, Leiden, 2005.

Lyushkevich, F. D., Clothing of ethnic groups of the population of the Bukharan oasis and regions adjacent to it. First half of the 20th century.

Experience of comparing characteristics [in Russian], Traditional Clothing of the Peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan, edited by N. P. Lobacheva

and M. V. Sazonova, page 134, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1989.

Morozova, A. S., Traditional Clothing of the Turkmen People [in Russian], Traditional Clothing of the Peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan,

edited by N. P. Lobacheva and M. V. Sazonova, pages 77 to 78, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1989.

Pirnazarova, A., Curator of Costume and Jewellery, Private Discussions, Karakalpak State Museum of Art named after Igor Savitsky, No'kis,

2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, and 2007.

Pisarchik, A. K., Material on the History of the Clothing of the Nurata Tajiks. Ancient Women's Dresses and Head Covers [in Russian],

Costume of the Peoples of Central Asia, edited by O. A. Sukhareva, page 116, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1979.

Sazanova, M. V., Women's Costume of the Uzbeks of Khorezm [in Russian], Traditional Clothing of the Peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan,

edited by N. P. Lobacheva and M. V. Sazonova, page 91, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1989.

Scarce, J., Women's Costume of the Near and Middle East, RoutledgeCurzon, London, 2003.

Shalekenov, U. Kh., Kazakhs of the Lower Amu Darya [in Russian], Fan Publishing, Tashkent, 1966.

Shaniyazov, K. Sh., and Islamov, Kh. I., Ethnographic Studies on the Material Culture of the Uzbeks from the End of the 19th to the Beginning

of the 20th Century [in Russian], Fan, Tashkent, 1981.

Shirokova, Z. A., Traditional Woman's Head Gear of the Tajiks (South and North Tajikistan) [in Russian], Traditional Clothing of the Peoples

of Central Asia and Kazakhstan, edited by N. P. Lobacheva and M. V. Sazonova, pages 187 to 199, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1989.

Sukhareva, O. A., Ancient Features in the Forms of the Headgear of the Peoples of Central Asia [in Russian], Central Asian Ethnographic

Collection, 1954.

Sukhareva, O. A., History of Central Asian Costume: Samarkand (second half of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century) [in Russian],

Science, Moscow, 1982.

Yatsenko, S. A., Late Sogdian Costume, Eran ud Aneran, Transoxiana, Universidad del Salvador, Buenos Aires, 2003.

Zadykhina, K. L., Socialist Reform of the Economy and Way of Life of the Uzbeks of the Kipchak Region [in Russian], Works of the

Archaeological and Ethnographical Expedition to Khorezm, pages 795 to 796, 1949-53, Volume 2, edited by S. P. Tolstov and T. A. Zhdanko,

Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1958.

Zakharova, I. V., and Khodzhayeva, R. D., The Head-gear of the Kazakhs [in Russian], Traditional Clothing of the Peoples of Central Asia

and Kazakhstan, edited by N. P. Lobacheva and M. V. Sazonova, pages 216 to 227, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1989.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

|

This page was first published on 7 March 2008. It was last updated on 6 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |