|

Contents

Introduction

Road Network

River Crossings

Rail Network

Air Links

River Transport

Aral Sea Shipping

References

Introduction

Due to its isolated and landlocked geographical location, transport links are a vital component of Karakalpakstan's economy. The populated regions

located around the banks and irrigation network of the lower Amu Darya are surrounded on all sides by desert - the Ustyurt plateau in the west, the

Qızıl Qum desert in the east, the Qara Qum desert to the south and the newly formed Aral Qum, left behind by the retreating

Aral Sea, in the north,

The Karakalpak Autonomous Republic mostly consists of uninhabited wilderness.

Image courtesy of MODIS Rapid Response System at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre, 2003.

In the past the main route into the Khorezm oasis was from the south-east along the valley of the Amu Darya. One route followed the southern bank

from Amul (modern Turkmenabat) while two other routes went via Bukhara, one passing straight through the Qızıl Qum to Kath, the other

passing closer to the Amu Darya via the Rabats of Tugan and Mash. However the region was also linked by means of a multitude of other desert

caravan routes, each supported by intermittent man-made wells and watering holes and throughout the past millennium by numerous caravanserais where

travellers could rest themselves and their animals overnight. One route from north-east Iran and the southern Caspian followed the route of the

Uzboy River to Gurganj (Kunya Urgench). Another crossed the Ustyurt from the Volga region of south-eastern Russia, while another ran south

from southern Siberia down the valley of the Turgay and the eastern edge of the Ustyurt, following the shoreline of the Aral Sea. In the east

there were routes running through the Qızıl Qum, the main one following the channel of the Jan'a Darya (from Bartigkent on the other

side of the Syr Darya from modern Qizil Orda). This was linked to a route running along the southern bank of the Syr Darya from the former oasis of

Otrar. From the south one route ran directly north from Merv up to the Amu Darya and then followed its left bank via Dargan, Sadvar, and Hazarasp to

reach Gurganj, while another went directly north from Nishapur to Nisa and thence to Gurganj.

Some of these ancient routes are still used today. For example the main rail and road link to Russia follows the old caravan route across the

Ustyurt to Beyneu and Saratov, while the primary land link from eastern Uzbekistan still follows one of the caravan routes from Bukhara and

the valley of the lower Amu Darya.

Most imports to and exports from Karakalpakstan are shipped by rail rather than road. Many of Karakalpakstan's exports tend to be bulky items: marble,

stone, building materials, soda ash, and raw cotton. Most imports relate to industrial equipment and piping for the natural gas extraction industry.

Visitors are frequently surprised about the relatively small amount of road freight passing between Karakalpakstan and the rest of Uzbekistan.

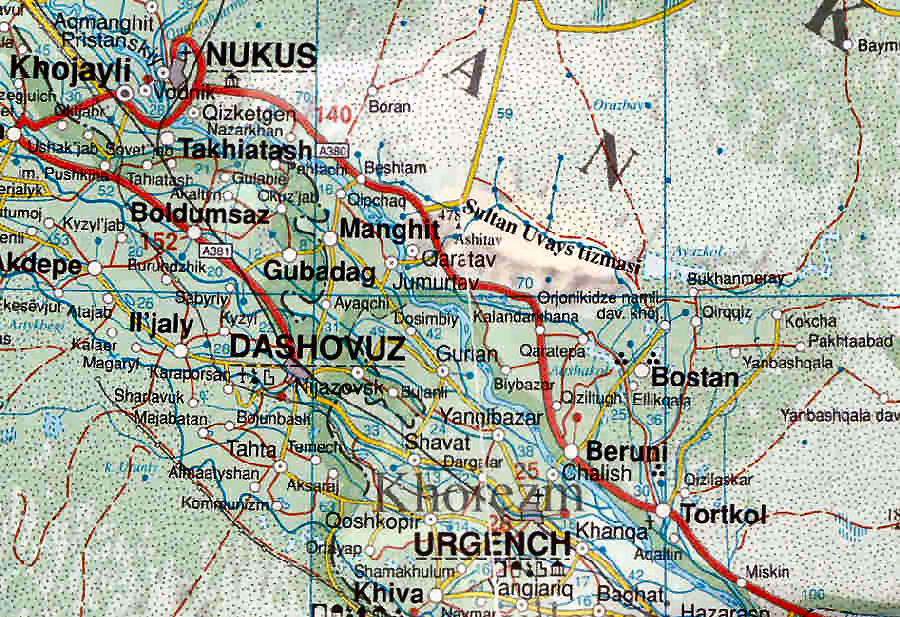

Road Network

For a small country Karakalpakstan has a well-developed road network, a legacy of former Soviet rule. No'kis is connected to the rest of Uzbekistan

by the A380 trunk road, which passes from Karshi to Bukhara and then crosses the Qızıl Qum close to the natural gas fields at Gazli to

reach the north bank of the Amu Darya at Lebap. It then follows the north bank of the Amu Darya river to cross the Karakalpakstan border just before

Miskin, passing through To'rtku'l and Biruniy before skirting the southern flanks of the Sultan Uvays Dag before reaching No'kis.

|

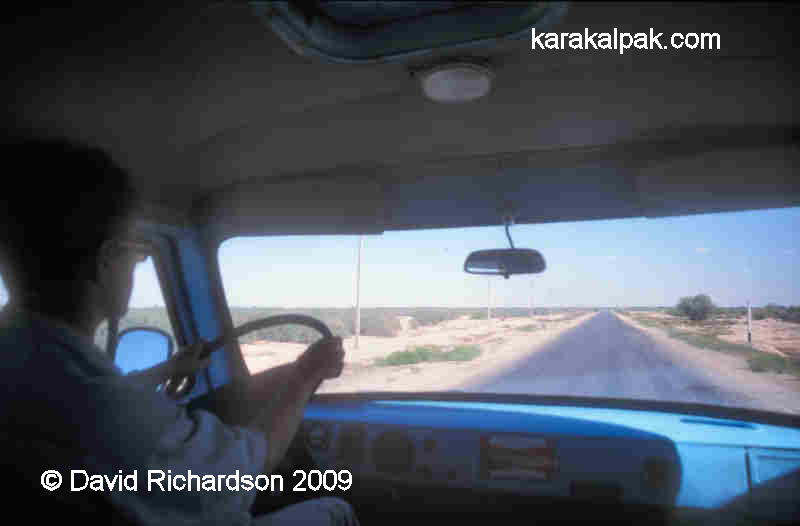

The relatively deserted main A380 highway from Bukhara to No'kis.

The A380 highway heading from No'kis to Bukhara from the air.

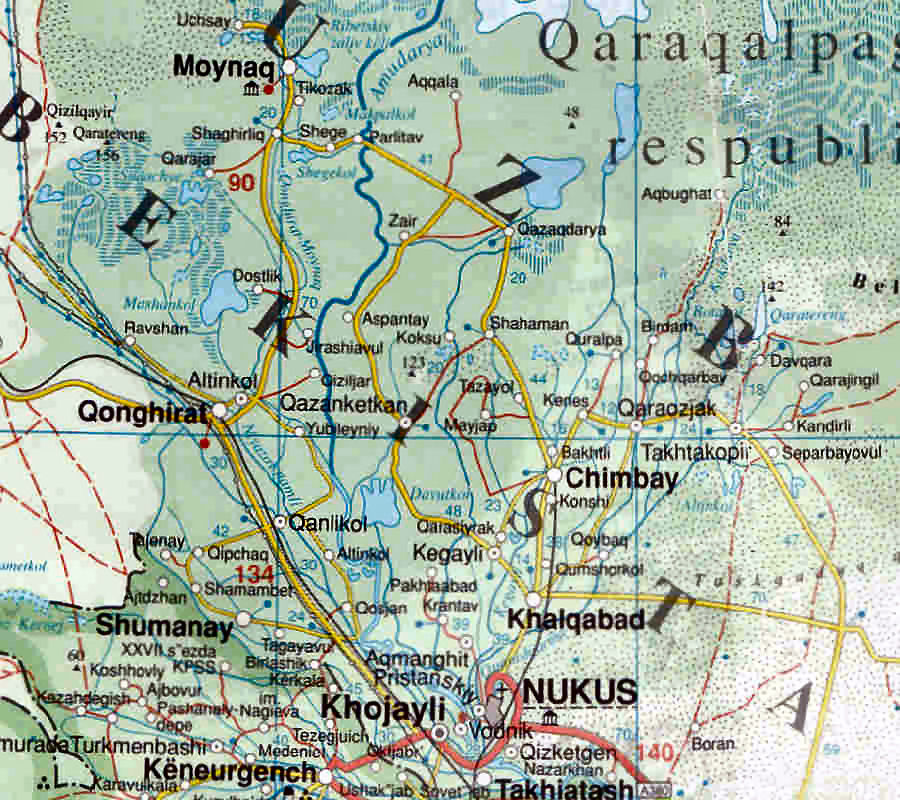

From No'kis the road crosses the Amu Darya and then heads northwest to Qon'ırat. Beyond Qon'ırat the condition of the road deteriorates,

firstly into a narrow metalled road as far as Jaslıq and then into a gravel track to the border and western Kazakhstan. This route is used by a limited

number of cars, buses, and trucks travelling to Central Asia from Russia.

The A380 running from Miskin to No'kis via Biruniy in southern Karakalpakstan.

The A380 from Qon'ırat to Bukhara is a wide two-lane highway with a relatively low traffic load. Average usage in Karakalpakstan in 2007 was

estimated to be less than 400 vehicles per day.

In 1999 the Council of Ministers of Uzbekistan approved a project to establish a 2,000 km long national highway crossing the entire country from Andijan

to Tashkent, No'kis, and Qon'ırat. Work on upgrading the route commenced in 2002. Since then the route has been assessed to be internationally

strategically important long-term, potentially linking southern Russia and western Kazakhstan to Tajikistan and northern Afghanistan by way of the

Uzbek-Afghan Bridge of Friendship at Termez. Currently two sections are planned to be widened into a four lane highway - a 40km stretch in the district

of Qon'ırat and a 91km stretch covering the district of Hazarasp in Khorezm viloyati and the district of To'rtku'l in Karakalpakstan.

The $75 milion project is being funded by the Asian Development Bank.

A second major highway runs north from No'kis to Xalqabad and Shımbay, where it divides, one branch heading north to Qazaqdarya, another heading

east to Taxta Ko'pir.

|

The road network connecting the main towns and villages of the northern delta.

Generally the road network covering the northern delta is in a good state of repair and is relatively underused. Roads tend to be generally wide and

straight. The busiest time is during the cotton harvesting season.

A very quiet road in the Ellikqala district of southern Karakalpakstan.

A long and empty country road lined with jide north of Bozataw in 2004.

The empty road from Qon'ırat to Moynaq in 2001.

No'kis is also connected to Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, by a narrow desert road that passes through the centre of the Qara Qum. The main

road from Xojeli to Kunya Urgench crosses the international border but then narrows into a single lane metalled road, which passes through featureless

desert until it reaches the outskirts of Ashgabat. There is only one main stopping point, at the small settlemet of Darvaza, a former Soviet sulphur mine.

River Crossings

There are numerous road and rail crossings over the lower Amu Darya, several new ones having been constructed since the collapse of the USSR. The most

important bridge in Karakalpakstan provides a road link between the capital No'kis and neighbouring Xojeli. It was built between 1999 and 2001. More

recently the "Amudarya" combined rail and road bridge was built in 2004 further upstream from just south of To'rtku'l in Karakalpakstan to Hazarasp in

the viloyat of Khorezm.

Crossing the new road bridge from No'kis to Xojeli.

The new Amudarya combined road and rail bridge close to To'rtku'l just after its opening in 2004.

A third modern road and rail link crosses the top of the Tu'yemoyın hydroelectric dam, built between 1981 and 1983 and linking No'kis to the neighbouring

industrial and residential town of Taqıatas.

Prior to the construction of these crossings, vehicles could only cross the Amu Darya by means of primitive pontoon bridges composed of a string of

connected barges held in place by cables and anchors. These had to be occasionally closed during the winter to allow the passage of ice down the

Amu Darya. To make matters worse they were inaccessible to large vehicles when river levels were especially low. Today there are three such pontoon

bridges serving Karakalpakstan:

- the first just north of Ma'n'gıt, linking Qıpshaq to Bestam, about 300 metres wide,

- the second linking Jumurtaw to Qarataw (close to ancient Gyaur qala), about 360 metres wide,

- and the third linking Chalish in the Khorezm viloyati to Biruniy, about 600 metres wide.

The decrepit pontoon bridge linking left bank Qıpshaq to right bank Bestam in 1999.

An Uzdaewoo Nexia crossing the pontoon bridge to Qıpshaq in 2004.

The Jumurataw-Qarataw pontoon is only lightly used by local traffic, whereas the Qıpshaq and Biruniy pontoons are always busy.

Cars leaving the Biruniy pontoon bridge on the Khorezm side in 2001.

An almost empty Biruniy pontoon bridge in 2005.

The latter two crossings are poorly maintained and welding teams work almost constantly repairing the uneven surface of metal plates.

Welders working on the Qıpshaq pontoon bridge in 2001.

Moving upstream beyond the borders of Karakalpakstan the next river crossing is located at the Drujba dam where a road runs north over the top of the

dam, crossing the border in the process from Gaz-Achak in Turkmenistan to Drujba in the Khorezm viloyati of Uzbekistan. This is the last

upstream crossing for 300km until the pontoon bridge in eastern Turkmenistan connecting Turkmenabat, formerly Chardjou, from Jeyhun and Farab. It sits

alongside the 1.7km long iron railway bridge built by the Russians in 1901 to replace the former wooden railway bridge built in 1887. Also in

Turkmenistan, a further 200km upstream, work continues on a new road bridge designed to replace the former pontoon bridge linking Atamurat (formerly

Kerki) with Kerkichi. The project, which began in 2001/2, is financed by the Ukraine in return for Turkmen natural gas but has been bogged down in

political wrangling since 2004.

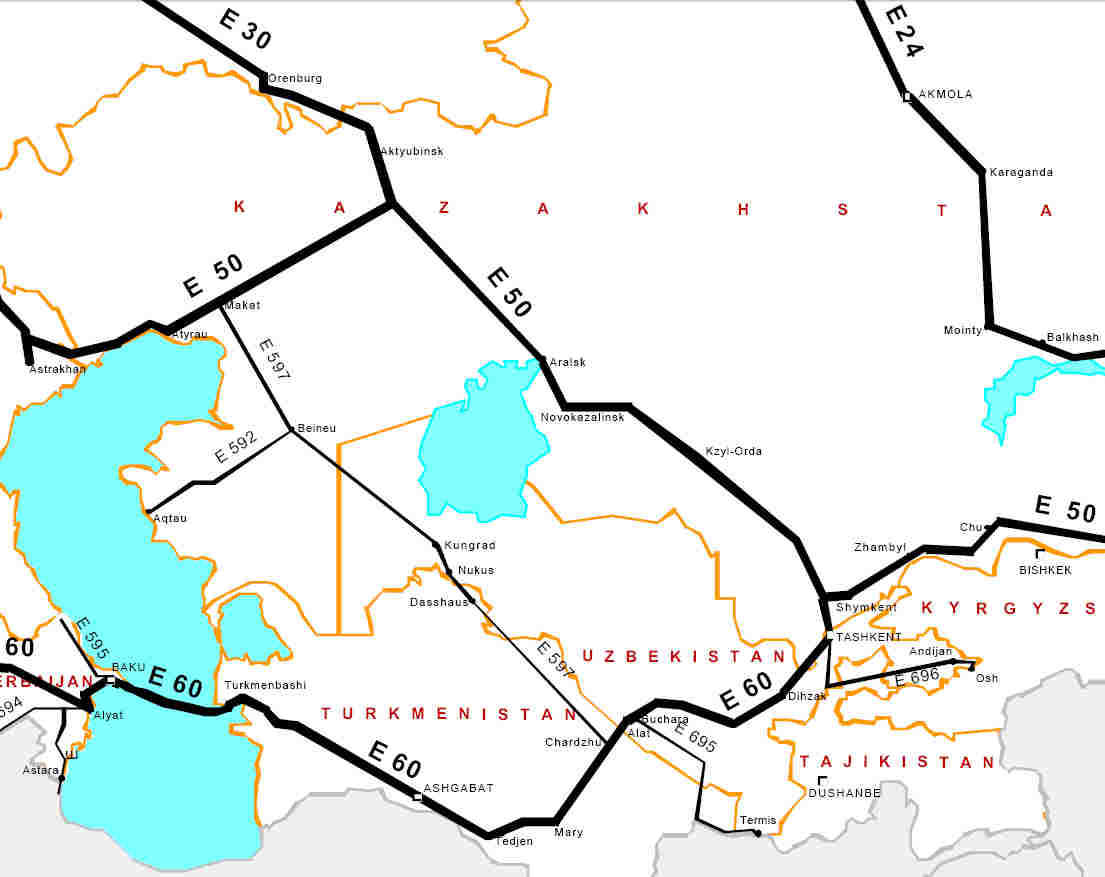

Rail Network

Karakalpakstan is served by an efficient railway system that links it domesticaly to Tashkent and internationally to western and eastern Kazakhstan

and Russia. No'kis railway station is modern, quiet, and clean and is linked to the nearby city centre by bus and taxi.

|

The modern railway station at No'kis.

During the Soviet era the railway line from Tashkent passed through Samarkand, which was linked to Kagan (close to Bukhara) by two branches - one

passing north via Navoi and the other south via Qarshi. From Kagan the line ran south crossing the Amu Darya at Turkmenabat (Chardjou) and then

followed the left bank of the Amu Darya before reaching Urgench, Dashoguz, Xojeli, and Qon'ırat (Kungrad). It then continued north to cross

the Kazakhstan border. No'kis and Shımbay were accessed by a spur from the main line at Taqıtas.

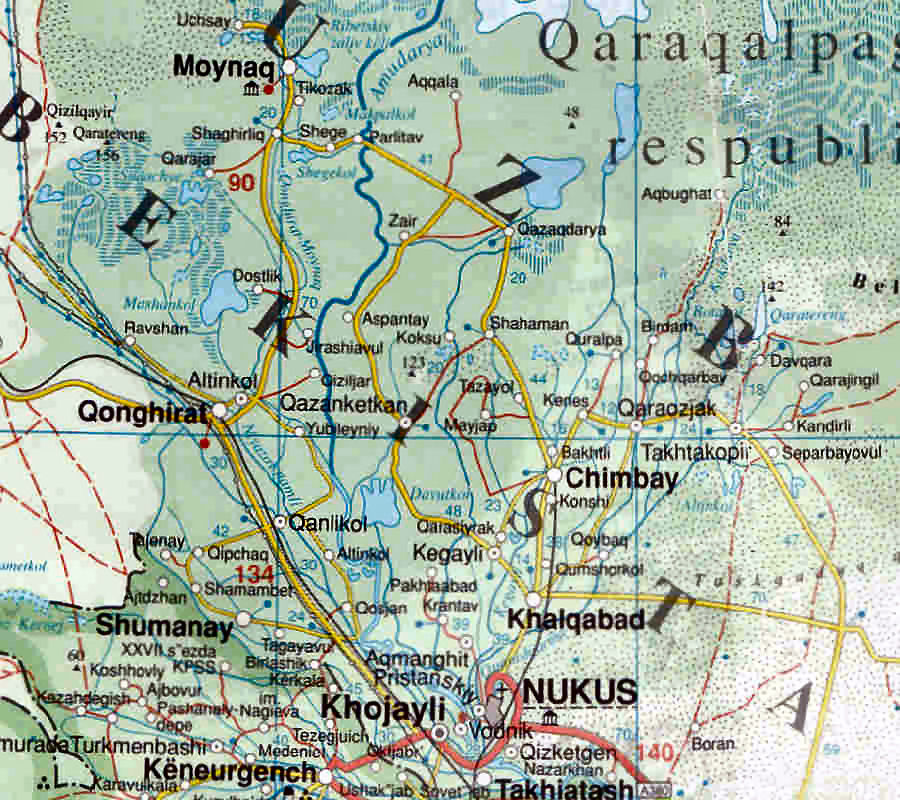

The railway network at the time of Uzbek independance.

Image courtesy of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Transport Division.

Following independence rail travel between Tashkent and Urgench and No'kis was hampered by immigration and customs disputes between Uzbekistan

and Turkmenistan. To resolve the problem the Uzbek government decided to build a self-contained national rail network by constructing a new 500km

long railway line across the Qızıl Qum from Navoi to Zeravshan and Uchquduq and then south to Miskin and To'rtku'l, skirting the southern

flank of the Sultan Uvays dag to reach No'kis. The line was partly built by the inmates of Uchquduq prison and was completed over a period of three

years. Following the construction of the new Amudarya rail and road brige a rail spur was added to link Miskin to the old railway line on the left

bank at Hazarasp, providing access to Urgench and Shavat.

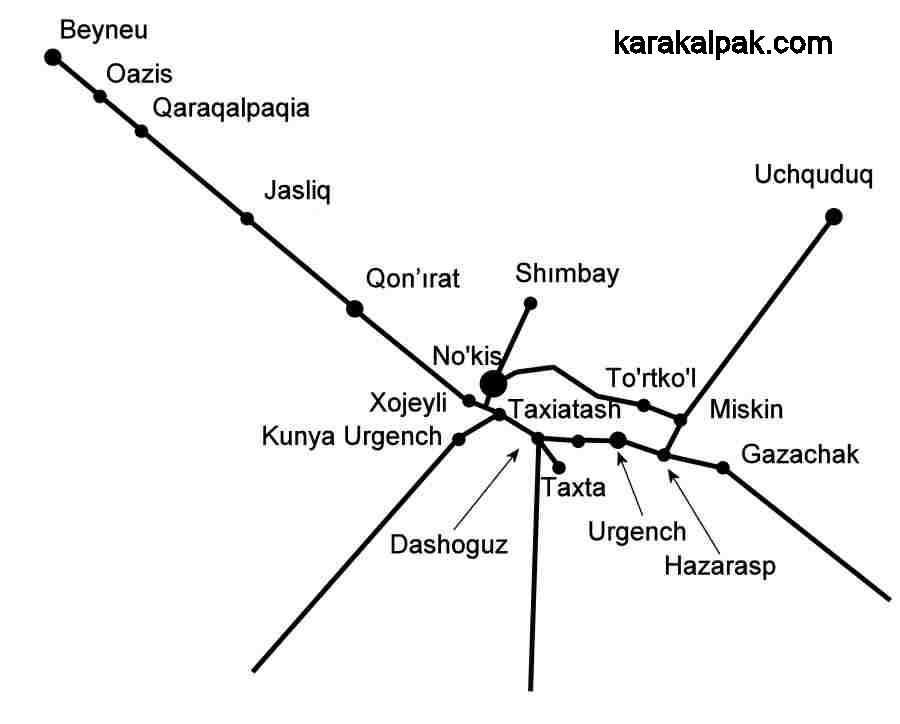

Schematic rail map of Karakalpakstan.

It takes 23 hours to travel from No'kis to Tashkent on the new line. This is slower than driving by road, although far less tiring and avoiding

numerous road check-points.

The two main international train routes passing through Karakalpakstan are:

- No'kis to Almaty, via Tashkent and

- Saratov (on the Volga) to Tashkent, via Karakalpakstan.

The train from Tashkent to Saratov.

Image courtesy of Helmut Uttenthaler.

There is also a Moscow service to Tajikistan which transits through Karakalpakstan but does not stop at any of the stations there.

The Almaty train terminates in No'kis after stopping at Miskin, To'rtku'l, and Kaibek. It takes 46 hours to reach No'kis from Almaty.

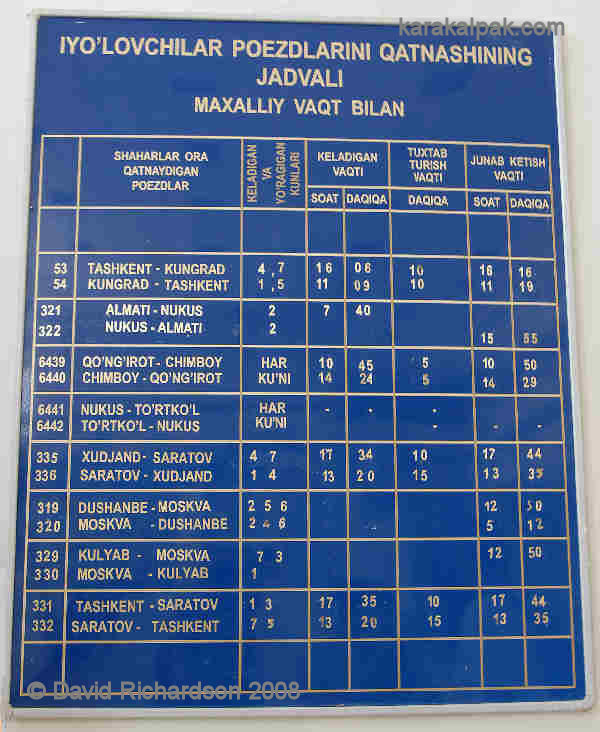

Train schedule at No'kis Station (in Uzbek).

There is also a train service between Kazakhstan and Karakalpakstan, taking 12 hours to run from Qon'ırat to Beyneu and stopping at all the small stations

along the way.

Air Links

Karakalpakstan is served by its own modern international airport located close to the centre of No'kis. Currently the only international flights

to No'kis are from Moscow. Both Uzbekistan Airways and Gazpromavia operate weekly return flights from Moscow's Domodedovo and Vnukovo airports

respectively. Click here for details.

No'kis International Airport.

Nearby Urgench International Airport also has a weekly flight to Moscow served by Sibir Airlines. Dashoguz airport in neighbouring Turkmenistan

provides frequent connections to Ashgabat.

No'kis is connected to Tashkent by means of two domestic flights a day, seven days a week, one flying from Tashkent and back in the morning and

another following the same route in the evening. There is also a weekly return flight from No'kis to Ferghana.

River Transport

In the past the Amu Darya provided a major transport route into and out of the region. However navigation of the Amu Darya has always been a

precarious venture requiring intimate knowledge of the constantly shifting sandbanks and shallows.

In the 19th century passenger and cargo vessels sailed downstream from Chardjou (modern Turkmenabat) to Khanqa - which provided access to Khiva by

canal - and on to Qıpchaq, Xojeli, and Qon'ırat. Boats returned under sail or were physically hauled back upstream by teams of barge haulers.

In 1899 Ole Olufsen sailed downstream from Chardjou in a wooden qayıq with a single square sail crewed by a dozen Turkmen, navigating

between sandbanks and islands. He visited Khiva, New Urgench, and Xojeli and returned via Hazarasp and Petro-Aleksandrovsk. Even at that time larger

Russian paddle steamers were working the river. Colonel Le Messurier observed in 1887 that two fast and armed steamboats were nearing completion at

Chardjou, along with two barges, having been transported there in parts by rail. In 1933 the intrepid Swiss traveller Ella Maillart travelled down

the same stretch of river on a paddle steamer called the "Pelican", taking six days to reach To'rtku'l. A high-speed "hydroglisseur" service was

already doing the same journey in six hours. Bales of Khorezmian cotton were being ferried upriver on square-sailed qayıqs. A small

boat took her further downstream where she took an arba (wooden cart) to New Urgench and Khiva. Back on the Amu Darya she caught the "Lastotchka" steamer

to the port of "Kant Uzak" in the northern delta, from where she planned to cross the Aral Sea to Aralsk before the service was suspended in late November.

When she arrived at the large river port at Xojeli she discovered that the port on the Aral was already closed – the last boat of the season, the

"Commune", had sailed the day before.

|

|

Qayıqs on the Amu Darya, probably 1930s.

Images courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

During the Soviet era long distance river travel became restricted by the construction of numerous permanent pontoon bridges and in the early 1980s

by the construction of the Tu'yemoyın hydroelectric dam. The majority of working boats on the river today are associated with the management and

maintainance of the remaining pontoon bridges.

An assortment of working boats on the Amu Darya in Karakalpakstan.

Sadly navigation on the Amu Darya downstream from the Tu'yemoyın dam is almost impossible today as a result of much lower river levels. The waters

of the once mighty Amu Darya have been syphoned off to irrigate the cotton and rice fields of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Karakalpakstan.

Very low water levels in the Amu Darya to the south east of No'kis.

In recent years the stretch of the Amu Darya that separates Khorezm from southern Karakalpakstan has seen the emergence of a new commercial phenomenon

- the introduction of a small pleasure boat service, offering local people the chance to dine "chaikana-style" while they cruise down the river.

Pleasure boats on the Amu Darya at Qıpshaq.

The main centre for these cruises is just south of the pontoon bridge at Qıpshaq.

Aral Sea Shipping

During the 18th and 19th centuries the Karakalpaks were able to navigate the east coast waters of the Aral Sea. The Russian envoy Dmitry Gladyshev

and his military surveyor Ivan Muravin visited the "lower" Karakalpaks near the mouth of the Syr Darya in 1740 and reported that they were able to

sail from there to the mouth of the Amu Darya using six metre long wooden boats with a single small sail.

However it was the Russians who launched the first large industrially manufactured ships onto the Aral Sea. The initial fleet of the so-called Aral

Flotilla consisted of two twin-masted schooners, the warship "Nikolay" and the merchant ship "Mikhail", both constructed in Orenburg in 1847. The

first was designed for surveying and the second for establishing a fishery, but neither were capable of safely venturing far into the Aral Sea with

its perilous shallows, and they became restricted to surveying the island of Kozaral in the mouth of the Syr Darya estuary and the other islands down

the eastern coast of the Aral Sea. Soon a somewhat larger schooner, the "Konstantin", was built in Orenburg and was used by Lieutenant Aleksey Butakov

to undertake the first complete survey of the Aral Sea in 1848 and 1849.

In 1850 the Russians ordered the construction of two new boats from a Swedish shipyard – the "Perovsky", a forty horsepower paddle-wheel steamboat,

and the "Obrutchef", a twelve horsepower propeller-driven iron barque. The "Perovsky" was launched at Fort Raim on the Syr Darya in 1853, two years

ahead of the "Obrutchef", and was armed with three nine-pound guns. However it proved to be too large for navigating the more difficult parts of

the Syr Darya and was continually running aground. In a whole season it could only make three round trips between Fort Kazalinsk and Fort Perovsky.

Both steam boats required huge quantities of saxaul to fire their boilers and on one occasion 180 tons of anthracite was especially transported

overland from the River Don at enormous cost!

As the Russians increased their stranglehold on Central Asia the Aral Flotilla - headquartered at Kazalinsk - was expanded further. By the eve of

the invasion of Khiva in 1873 the fleet consisted of three side-wheel paddle steamers, the "Perovsky", "Samarkand", and "Tashkent", two stern-wheel

steamers, the "Aral" and the "Syr Darya", both armed with nine-pound guns, a steam launch, and many barges including three that were schooner-rigged.

The two stern-wheelers were flat-bottomed and were constructed by the Hamilton Works in Liverpool in 1861. The individual parts were shipped to

Orenburg, carried across the steppes by camel – an incredible feat of transportation – and then finally assembled as boats at Kazalinsk. However

they turned out to be less satisfactory than the earlier steamboats, partly due to the poor quality of their final construction. The later

"Samarkand" was built in Belgium in 1866 and the more recent "Tashkent" made in Russia in 1870.

After the Russian conquest in 1873 the Russian paddle steamer "Perovsky" could ferry passengers from Kazalinsk to the Amu Darya across the Aral Sea,

making it possible to reach Khiva from Orenburg by carriage and boat without the perilous crossing of the Ustyurt. With the construction of a new

railway line from Orenburg to Aralsk in about 1900, and its extension to Tashkent in 1906, goods could now be transported by rail to Aralsk and then

shipped across the Aral Sea to Khorezm. Unfortunately the service could not operate during the winter because the northern Aral Sea became ice bound.

Both Aralsk and Xojeli began to develop into shipbuilding centres to provide vessels for this new Aral Sea route.

|

Qayıqs at the port of Moynaq, probably photographed in the 1930s.

Image courtesy of the Savitsky Museum, No'kis.

The full commercial exploitation of the Aral Sea occurred during the Soviet era. Between 1933 and 1941 Moynaq developed into a major fishing centre

supported by up to 113 fishing vessels working the Aral Sea. Nearby U'shsay became the main commercial port for the transport of cargos to and from

the port of Aralsk in Kazakhstan.

Painting of the old cargo port at U'shsay by F. Madgazin.

Boats at the port of U'shsay at some time prior to 1967.

Image courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

However the relentless development of the Uzbek cotton industry meant that less and less water was draining into the Aral Sea. The development of the

Qara Qum Canal in the 1950s was the final straw - from 1960 onwards the level of the Aral Sea began to fall. At first the decline was small

because of compensation from the draining of the lakes within the delta and releases from the surrounding water table. Some of the first people to

recognize the problem were the Aral fishermen, who noticed the level of the highest tide falling relentlessly from 1964 onwards. Soon the port at

Moynaq began to dry up and Toqmaq Ata Island gradually became connected to the mainland. At first the fishermen were forced to relocate their boats

from the fishing port to the cargo port at U'shsay. But in time this also began to run dry and channels had to be cut to allow the boats to reach

the Sea. It was an impossible battle and eventually the ferry service was terminated and the bigger fishing boats were left stranded on the dried-up

seabed. The rusting hulks that remain today in the so-called "ships' graveyards" at Moynaq, U'shsay and Aralsk are only a fraction of the original

fleet, many of which were subsequently dismantled for scrap.

|

Skeleton of a small boat at the Ship's Graveyard near Moynaq.

The "Karakalpakia" repainted for a movie by a visiting film crew.

Rusting hulk on the former bed of the Aral Sea.

By 1970 the shoreline had receded by about 10 km, leaving the community of Moynaq stranded and its former fishermen unemployed. The small town of

U'shsay that was once home to one thousand fishing families had lost its livelihood and would gradually decay into the ghost town that remains today.

The empty Aral Sea, devoid of a single ship.

Today the Aral Sea has almost gone - all that remains currently are a handful of large lakes. However the western basin is still a substantial size,

measuring over 160km from north to south. Yet without any port of access it remains eerily silent, devoid of a single floating vessel of any kind.

The Aral Sea shipping route is no more. To travel from No'kis to Kazalinsk or Aralsk it is now necessary to go by train or air via Tashkent and Almaty.

References

Anon., Soviet Topographical Military Map Series, Uzbekistan [in Russian], Scale 1;100,000, Roskartographia, Moscow, 1942, Revised in 1989.

Anon., Central Asia, Road Map, 1:1,750,000, Freytag and Berndt, Vienna, 1998.

Anon., Republic of Uzbekistan: CAREC Regional Road Project, Asian Development Bank, May 2008.

Anon., Uzbekistan Today, Tashkent, 5 January 2007.

Buryakov, Y. F., Baipakov, K. M., Tashbaeva, Kh., and Yakubov, Y., The Cities and Routes of the Great Silk Road, International Institute for

Central Asian Studies, Sharq Publishers, Tashkent, 1999.

Maillart, E. K., Turkestan Solo, translated by John Rodker, G P Putnam's Sons, New York, 1935.

Nurmukhamedov, M. K., Muminov, I. M., and Dosumov, Y. M., History of the Karakalpak ASSR, Volume 2, Fan Publishing, Tashkent, 1986.

Olufsen, O., The Emir of Bukhara and his Country, Elibron Classics, facsimile of 1911 edition, 2002.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|

|