Formation of Karakalpakstan

|

Formation of Karakalpakstan

|

|

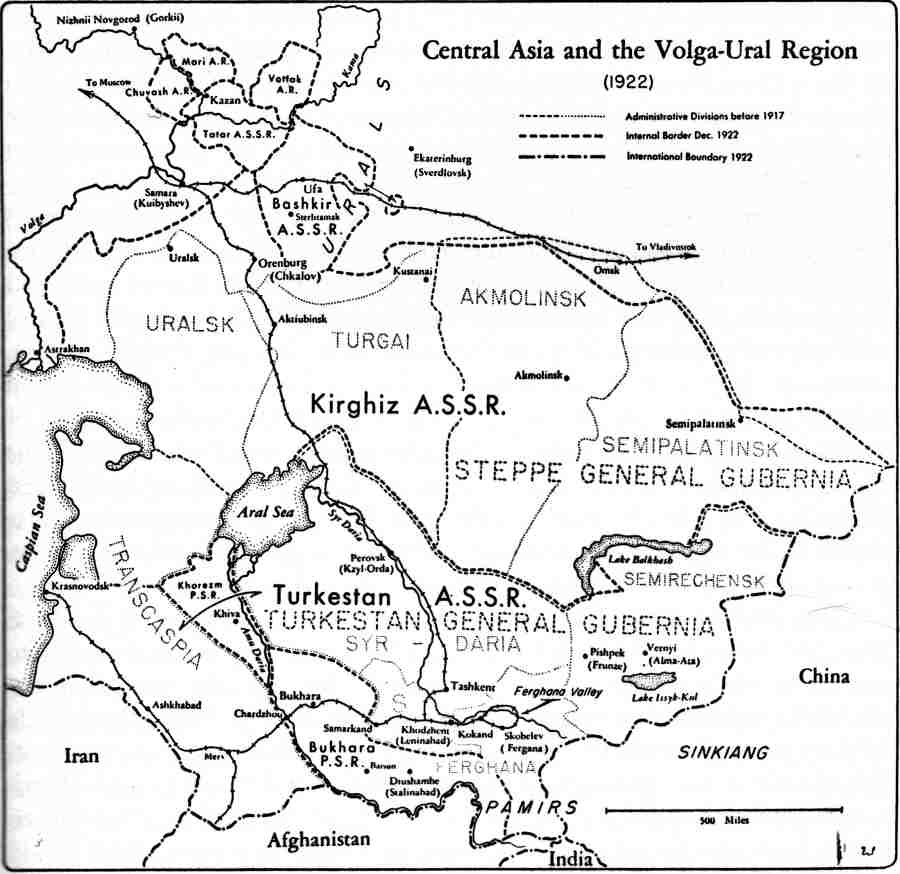

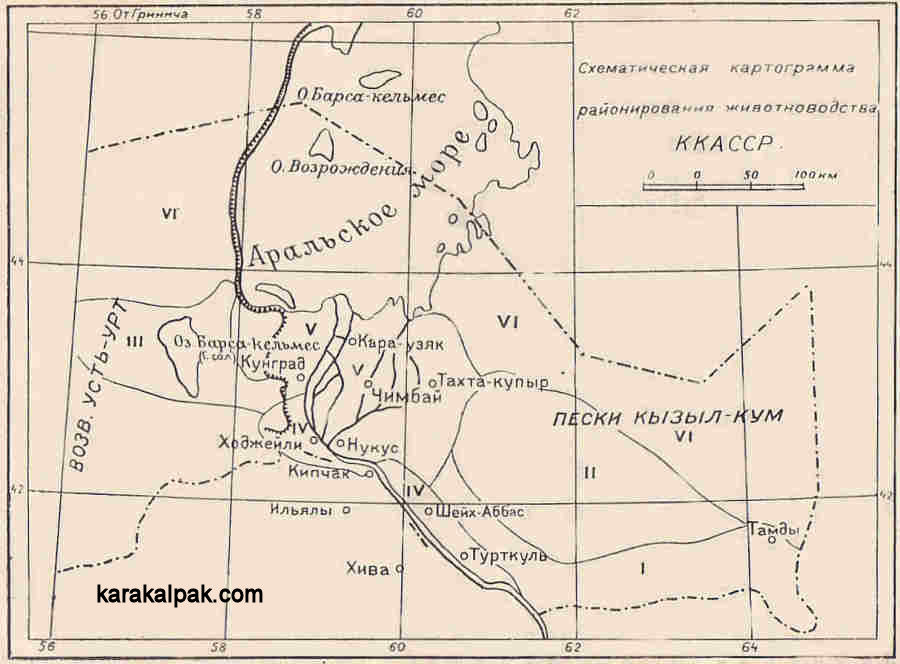

ContentsIntroductionRussian Annexation The Amu Darya Otdel Rising Unrest in Russia The Russian Revolution Reaction in Turkestan Reaction in Khorezm Descent into Civil War The Khorezm Peoples' Soviet Republic The Khorezmian Soviet Socialist Republic Soviet National Delimitation Policy The Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast The Karakalpak Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic Entry into the Uzbek SSR Post Script References IntroductionKarakalpakstan is an artificial nation, its arbitrary borders drawn across uninhabited stretches of desert and the middle of the Aral Sea by Soviet apparatchiks in the early 1920s. Thus its entire western frontier is determined by the 56th meridian. Its only natural borders are a small section of tchink, along the edge of the Ustyurt plateau (part of which is currently disputed by Turkmenistan), and the right bank of the Amu Darya from Nazarkhan to Drujba.

The arbitrarily drawn borders of todays Karakalpak Autonomous Republic run through remote uninhabited

stretches

|

|

Aware of British concerns over the continued expansion of Russia towards India, Kaufmann was under strict orders not to annex Khorezm – like Bukhara,

the Khanate of Khiva was destined to become a Protectorate of Russia, its Khan being allowed to continue to rule provided that hostilities ceased,

reparations were paid, Russian and Persian slaves were released, and Russian merchants were allowed to establish businesses and trade in the Khanate.

Instead Kaufmann annexed the lands on the right bank of the Amu Darya, forming a new otdel or department to be incorporated within the Syr

Darya Oblast. It was placed under the control of the Russian army who established a new military garrison at Fort Petro-Aleksandrovsk. Its

first Commandant was General Ivanov. In 1874 work began on the construction of a second garrison at Fort Nukus.

The Amu Darya Otdel had two regions, the Shoraxan section in the south and the larger Shımbay section in the north. The majority of

Karakalpaks (about 85%) lived on the right bank and became Russian subjects, leaving the remainder under the rule of the Khivan Khan.

Great interest was shown internationally in the new Russian conquest, but after a few years this began to wane. By the start of the 1900s the Khiva

Khanate and the Amu Darya Division had become forgotten backwaters of the vast Russian Empire. Although Russian merchants had arrived to establish

trading posts and new cotton plantations, the majority of Khorezm's people continued to follow their traditional medieval lifestyle.

Rising Unrest in Russia

Throughout the 19th century there was ever rising pressure against the tsarist regime in Russia, fuelled by the smouldering resentment of the

peasantry towards their feudal masters. Peasants made up about 90% of the population in 1800 and they were effectively owned by their aristocratic

masters, not even free to leave their own villages.

Following Russia's humiliating defeat in the 1854-56 Crimean War, Tsar Aleksandr II introduced some important reforms. The 1861 abolition of serfdom

theoretically freed the peasants, allocating them a portion of their landlord's land. However the reforms had been carefully designed to keep the

peasants tied to the land, ensuring that they would not pose any challenge to the Tsar's absolute autocracy. The landlords had been compensated with

government bonds and so in turn the peasants had to make redemption payments to the state over a period of 49 years. Each village commune or

mir held the peasant land in collective ownership and became responsible for seeing that the redemption payments were made.

Opposition to the tsarist regime had taken many forms during the first half of the 19th century, ranging from the Decembrists to the Nihilists, and

the Westerners to the Slavophiles. In the 1860s the new Populist movement became fashionable, promoted by anti-capitalist agrarian socialists who

argued that traditional village communes should form the basis of a future socialist state. Some believed that socialism could be achieved through

the education of the peasants, but the peasants were suspicious of urban do-gooders and over time the movement became more militant, supporting a

campaign to assassinate government officials.

The assassination of the Tsar in 1881 by an extremist wing known as the "People's Will" simply led to a return to repression under his son, Tsar

Aleksandr III, and an end to reformist thinking. Liberals were dismissed from their posts and the powers of the landlords and secret police were

increased. Tsar Nicholas II (1894-1917) maintained this reactionary position until the end of the 1903-1905 Russo-Japanese War.

In the 1880s further radical movements emerged. The Social Revolutionaries wanted to overthrow the regime and replace it with an agrarian society

based on the collective ownership of the land through the peasant communes. Meanwhile the Social Democrats adopted Marxist ideas, believing that

industrialization would lead to the growth of a large urban working class and ultimately revolution. They formed the Russian Social Democratic Labour

Party in 1898 but it soon divided into opposing camps. Its Second Congress had opened in Brussels in 1903 but was forced to move to London following

police harassment. The majority, known as the Bolsheviks and supported by Lenin, believed that the liberation of the working class could only be

achieved under the leadership of a small number of ruthless professional revolutionaries, while the minority Mensheviks under Martov supported wider

party involvement. Over the following decade the Bolshevik movement continued to strengthen, increasingly raising funds through criminal activities.

The last 20 years of the 19th century witnessed rapid industrialization in Russia, with an increasing number of employees working long hours in

poor conditions. Although illegal there had been a mounting wave of strikes by discontented workers, many of which were put down by the army.

There was also a rising radical student movement in the universities. A national university strike in 1899 was followed by a peasants' revolt in

the Ukraine in 1902 and a socialist terrorist campaign resulted in the assassination of several ministers.

A disastrous war with Japan over Russia's attempt to annex Manchuria only increased dissent. In early 1905 tsarist guards butchered a peaceful

workers' march on the Winter Palace. "Bloody Sunday" as it became known caused a wave of revulsion and unified political opposition. Strikes

and peasant riots eventually escalated into a general strike later that year. The Tsar, unsure as to whether or not to use force, finally opted for

limited reforms including an advisory parliamentary assembly, the Duma, with an upper house (the State Council) and an elected lower house

(the State Duma). However the absolute power of the Tsar was retained and Nicholas II had no hesitation in dissolving the first two Dumas when

they failed to cooperate.

|

The composition of the third Duma was more conservative, with less representation of the lower classes. It lasted for a full five years, from

1907 to 1912, combining repression with a few reforms and an associated period of relative calm. Prime Minister Stolypin sought to gain peasant

support by creating a class of independent and prosperous peasants. Redemption payments were cancelled, loan facilities were made available,

and peasants were encouraged to consolidate their land into larger farms, to sell and buy land, and to move or migrate. The scheme had limited

success – for example some 3½ million peasants moved to Siberia to establish new farms. However the majority of peasants were risk-averse and

remained in their communes.

Stolypin's reforms created enemies among the right-wingers in the Duma. For reasons that remain unclear he was assassinated by a revolutionary

in late 1911. Industrial unrest became more widespread, made worse by the shooting of 200 strikers at the Lena goldfields in Siberia. Meanwhile

agrarian disturbances broke out across the countryside in response to the imposition of the land reforms. The fourth Duma 1913-17 gave up any

further attempts at reform and was effectively ignored by the tsarist government.

The Russian Revolution

In 1908 the Austrians annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, causing enormous resentment in Serbia. When Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated during a

provocative visit to Sarajevo in 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war against Serbia, an ally of Russia. Russian forces were immediately mobilized.

Russia's initially successful invasion of East Prussia in 1914 soon turned to disaster when Germany opened up its eastern front in the following year

and decimated the poorly led and poorly equipped Russian troops. The Russian Army adopted a scorched earth policy creating an enormous refugee problem.

The massive demand for conscripts and materials led to major economic hardships throughout Russia, including high inflation and food shortages.

Every sector of the population became disaffected with the regime.

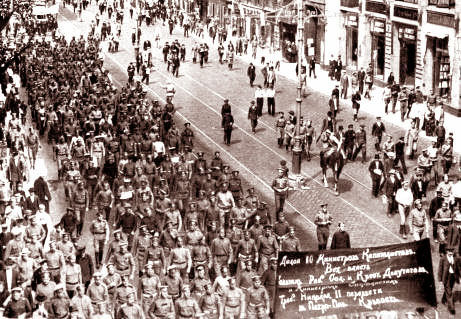

In February 1917, on the anniversary of Bloody Sunday, a major strike in Petrograd passed off peacefully. Later that month a local steelworks

closure coincided with women's demonstrations over bread shortages and escalated over a few days into a revolutionary insurrection. Military

intervention was ordered but the troops sided with the demonstrators. Railway workers pulled up the tracks to prevent the arrival of reinforcements.

In the face of universal hostility Tsar Nicholas II was finally persuaded to abdicate in favour of his brother, Grand Duke Michael. Yet the Grand

Duke turned out to have no desire to become Tsar, bringing the Romanov dynasty to a sudden end. Local activists had meanwhile established the

Petrograd Soviet, which in turn led to the formation of a Provisional Government under Prince Lvov. An amnesty for political prisoners led to the

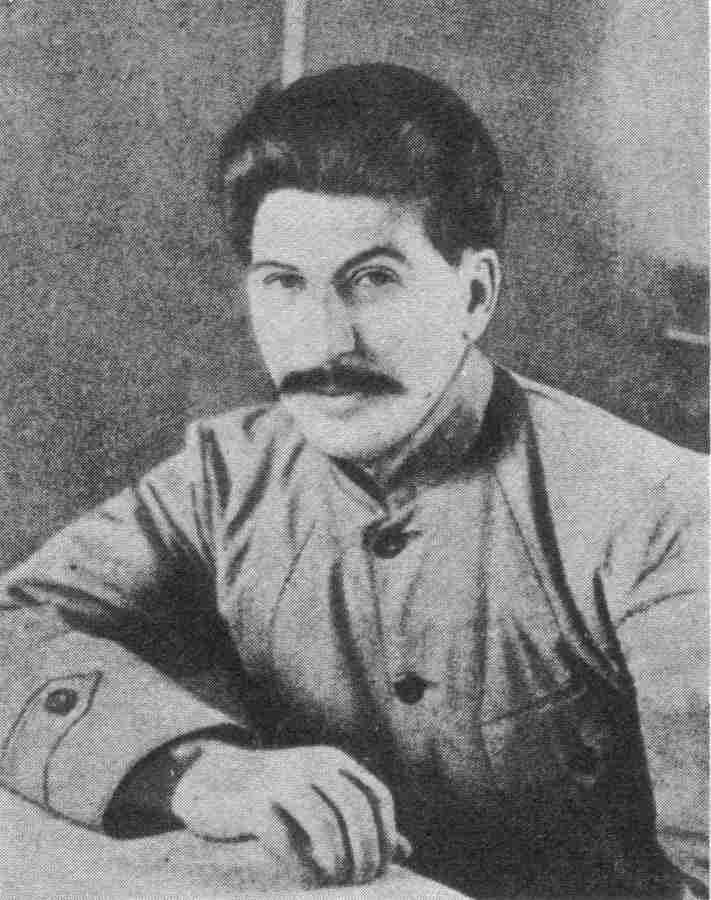

return of many exiles from Siberia, including Josef Stalin.

All of these developments came as a big surprise to the Bolshevik leadership. Lenin managed to return to Petrograd in April with help from the

German General Staff who hoped the revolution would undermine the Russian war effort. However the Provisional Government attempted to continue

the unpopular war against Germany, leading to increasing economic collapse and rising lawlessness at home. Fears of a Russian military

counter-revolutionary coup against the Petrograd Soviet greatly benefited the Bolsheviks who were seen as the only untainted defenders

of ordinary people's rights. Bolsheviks began to control an increasing number of factory soviets.

|

|

With the growing popularity of the Bolsheviks and the increasing isolation of the Provisional Government, Lenin decided that the time was right

to take control and urged the Central Committee to seize power. On the night of 6 November 1917 (24 October in the Russian calendar) a group of

Bolsheviks led by Trotsky staged a coup d'état storming the Winter Palace and ousting the Provisional Government. The military failed to

intervene. Within days Lenin had established the All-Russian Congress of Soviets. A new Council of People's Commissars was formed, consisting solely

of Bolsheviks, with Lenin as its Chairman.

Reaction in Turkestan

Tashkent at that time was a divided city, with the new Russian enclave sitting outside the much larger and older Muslim city. News of the Tsar's

abdication led to an upsurge in revolutionary activity, but only in the Russian quarter. Local Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks, and

Bolsheviks who were Russian émigrés, union leaders, and railway workers from the local railway workshops, established the Tashkent Soviet of

Workers and Peasant's Deputies, soon to be known simply as the Tashkent Soviet.

Meanwhile the new Provisional Government in Petrograd had issued instructions for the formation of a civilian Turkestan Committee in Tashkent,

a body of former tsarist officials composed of five Russians and four Muslim natives, to take responsibility for ruling Turkestan in place of

the office of the current military governor-general, General Kuropatkin. The authority of the Turkestan Committee was also to extend over the

Khanates of Khiva and Bukhara.

Throughout 1917 the local Tashkent Soviet progressively ousted power from the official Turkestan Committee. In November they took control of

Tashkent fortress and arrested members of the Turkestan Committee. Within weeks a Congress of Soviets proclaimed Soviet rule throughout Turkestan

and established Turksovnarkom, a Turkestan Council of People's Commissars, headed by a prominent local Bolshevik.

Neither the Tashkent Soviet nor the Turksovnarkom contained a single representative of the local Muslim people, who accounted for 95%

of the population of Turkestan. The Tashkent Soviet was little more than a bunch of émigré roughnecks with a Russian colonial mentality and they

were happy to apply the idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat to the native masses of Central Asia.

The conservative Muslims of Central Asia had little interest in all of this revolutionary fervour. There were small movements of intellectuals

across Central Asia who sought reform, but of a very different type from that espoused by Marx or Lenin. They were mainly the sons of tribal

aristocrats, bays, and rich merchants, educated in local Muslim schools, Russian Universities, or in Istanbul, and they mainly wanted

modernization and autonomy.

The Jadidist movement (from the Arabic usul-i jadid, meaning new method) had sprung from the writings of Ismail-bey Gasprinsky, a Crimean

Tatar, who was a proponent of a new phonetic method of language teaching. Dissatisfied with the backwardness of Central Asia, Jadidists wanted to

reform education, apply modern science, create new civic institutions, and improve the position of women. The separate concept of Pan-Turkism was

actually a Western idea, initially proposed by the Hungarian Orientalist Arminius Vambery, who envisioned an alliance of Turkic speakers from the

Bosphorus to the Altai. The idea was later promulgated by Gasprinsky and was adopted by some Jadidists. Pan-Turkists sought greater political and

cultural unity between the Turkic peoples and liberation from colonial oppression. Some Jadidists also had nationalist leanings and wanted an

autonomous Turkestan state, not necessarily independent from Russia. At the time of the revolution Tashkent was the main Jadidist centre in Central Asia,

followed by Kokand, Samarkand, and Bukhara. There were less than 50 Jadidists in Khiva.

The Jadidists saw the Revolution as an opportunity to gain autonomy and self-governance, although not necessarily complete independence from Russia.

In April 1917 liberal Muslims had formed the Turkestan Muslim Central Council in an attempt to create a voice for the local native population. In May

they attended an All-Russian Muslim Congress in Moscow, which proposed that the Muslim territories of Russia should be governed within a democratic

federal republic. In November 1917 the Muslim Central Council approached the Turksovnarkom on the issue of Turkestan autonomy and were told

that the Soviets opposed the idea. Indeed the Congress of Soviets had already arrogantly resolved that Muslims should in any event be excluded from

all government posts because of their uncertain attitude and lack of proletarian organizations. Local Muslim activists appealed to Moscow to rein in

the Tashkent Soviet, but Stalin refused to intervene in this distant dispute. For many local Russians, Pan-Turkicism sounded like a form of Pan-Islamic

fanaticism, or worse a return to Mongol rule.

The Muslims decided to organize an Extraordinary Congress in Tashkent to discuss the future status of Turkestan, but because of concerns over possible

military intervention chose to hold it in the nearby Muslim enclave of Kokand. The Congress declared its desire for a Pan-Turkic confederation of

progressive Central Asian states, for the education and Westernization of its people, and for the modernization of its religious establishments.

The territory of Turkestan was to be autonomous but united with the Russian democratic federal state. The Congress concluded by challenging the

Soviets in Tashkent, establishing an independent provisional regional government led by young nationalists – the Turkestan Autonomous Government -

with a Peoples' Council and an Executive Committee under the head of the clergy.

The Kokand national government was a direct and potentially highly popular threat to the existence of the Turksovnarkom and at a

Qurultay of Soviets held in Tashkent in January 1918 it was declared "counter-revolutionary". Within a month Red Army forces had surrounded

and invaded the city, destroying it by fire and causing considerable loss of life. Only a handful of fugitives survived to tell the tale.

Emboldened by their success, the Tashkent Bolsheviks turned their attention towards Bukhara but their attack on the city ended in defeat. Nevertheless

Tashkent still controlled the Syr Darya, Ferghana, and Samarkand regions and throughout the remainder of 1918 and most of 1919 it persecuted their

indigenous populations, looting their homes, expropriating their lands, and creating widespread antipathy against the Soviets that would reassert itself

later through support of the popular Basmachi movement.

Meanwhile the Soviet regime in Moscow was becoming increasingly unhappy about the rising hostility towards the Bolshevik regime in Tashkent. In April

1918, with the backing of Stalin, a special emissary was sent to Tashkent with orders that Turkestan should become an autonomous republic. The local

Bolsheviks obediently held a congress and unenthusiastically formed the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic or ASSR, although it would be

several years before any natives actually participated in its governance.

Reaction in Khorezm

In remote Khorezm few local people had any comprehension of developments in Russia. They were mostly poor, uneducated, illiterate, unorganized,

and overwhelmingly agrarian. There were no local newspapers, no railways, no non-Russian schools, and the only industrialization amounted to about

a dozen cotton mills. Soviet historians made much about disputes in the early 1900s over wages and conditions by Aral fisherman, barge haulers,

and soldiers and sailors in the Aral Flotilla, but such incidents were relatively minor and their importance may have been overemphasized. The

small local Russian merchant community, concentrated around Urgench and Petro-Aleksandrovsk, were more aware of developments in Petrograd especially

as some revolutionaries had been exiled to Petro-Aleksandrovsk prison.

Muhammad Rahim Khan II died of a heart attack in 1910 and was succeeded by his son, the weak and ineffectual Isfandiyar Khan (1910-1918). However

Isfandiyar's father-in-law and Divan-begi (effectively his Prime Minister), Islam Khoja, was quite the reverse - a dynamic individual who had

been influenced by his visits to Paris and Saint Petersburg and did much to drag Khiva into the 20th century, introducing the telegraph and building

the first post-office, first hospital, first pharmacy, and first Russian school. Sadly this very popular Minister was assassinated in 1913, his

modernist educational reforms having antagonized the traditional clergy. It is believed that his assassination was ordered by his archenemy, Nazar

Beg, the war minister, and was tacitly approved of by Isfandiyar Khan.

|

The main local disputes revolved around discrimination, taxation, water rights, military service, and firewood. The main expression of discontent

came from the local Turkmen population who were antagonistic towards the settled Uzbek majority and the taxes and restrictions on water rights

imposed upon them. In 1912 Isfandiyar Khan reformed the local tax system, which doubled or tripled the tax burden on the Turkmen. It needed only a

spark to ignite an open rebellion. When the Khan's officials killed a leading Turkmen for failing to hand over a criminal the local Turkmen tribes ran

riot, plundering Uzbek settlements close to Ilyaly. Nazar Beg led a punitive expedition against the Turkmen in January, but was held off for

twenty days by the well-entrenched rebels led by Muhammad-Qurban Serdar Junaid Khan, a Yomut chief. It was only after a detachment of Cossacks arrived from Petro-Aleksandrovsk

that the Turkmen agreed to a diplomatic settlement negotiated by Islam Khoja at Konya Urgench, which involved the withdrawal of the tax increase and

the payment of a one-off fine instead. The troubles surrounding water and taxation continued through 1914 into 1915. Von Martson, the exasperated

Russian governor of Turkestan, installed a Russian garrison at Khiva for the Khan's protection, even though he realized that the Khan was chiefly

to blame for his own problems. In early 1916 both the Turkmen and the Uzbeks protested against the Khan and Junaid Khan overran Khiva again, proclaiming

himself Khan. He was driven out by forces under General Galkin, governor of the Syr Darya Oblast. Petrograd ordered von Martson to

abandon his policy of support for the Turkmen and to teach them a severe lesson instead. The violent Russian reprisals lasted for two and a half

months and obliterated many local Turkmen settlements, installing deep bitterness among the local Turkmen community.

In July 1916 widespread rebellion broke out across the whole of Turkestan and the Steppe Region. The cause was an Imperial Decree cancelling the

immunity of non-Russians to military conscription. The Russians needed Central Asians for labour duties in the rear of their own forces engaged in

the First World War. This clumsy and unexpected announcement came at the height of the cotton-growing season and caused violent revolts throughout

Turkestan. The Khanates of Khiva and Bukhara were excluded from this Decree and were therefore spared from further rioting, but the Amu Darya

Otdel was not. There were numerous disturbances in right bank Khorezm, the worst being on 29 July when 600 Karakalpaks killed the local

chief of police and his wife at Shımbay. Some sense of the extensive disruption caused throughout the Khanate by the various internal disorders during

1916 can be gauged by the fact that the cotton harvest was only half of the level of the previous year.

Meanwhile the decision by the Russian authorities to commandeer large swathes of tugay forest in the Amu Darya Division for the

commercial production of firewood led to enormous resentment by Karakalpak and other peasants living in the delta, who could no longer use these

areas for grazing or for collecting firewood.

The Tsar's abdication caught Isfandiyar Khan by surprise while he was spending the winter in the Crimea and he was escorted back to Khiva by a

detachment of Russian troops. Meanwhile the Khivan Jadidists, who were all Uzbeks, had allied themselves with the soviet formed by the Russian

garrison in Khiva. They persuaded the Khan to issue a manifesto of reforms, just as the Emir of Bukhara had done a few weeks earlier. The

manifesto was actually composed by the Jadidist leader, Husayn Beg Matmuradov, and promised a constitutionally elected government, civil liberties,

a judiciary, and improvements to the schools, railways, and the post and telegraph service. A Khivan Majlis was then assembled, consisting

of thirty bays from each region of Khorezm but excluding any representatives from the Turkmen population. Matmuradov was duly elected

Prime Minister. It was only later, following pleas from the local Russian commander, that seven Turkmen chieftains were subsequently invited to

join the Majlis.

This concession failed to satisfy the troublesome Yomuts and by May 1917 they were back again, pillaging local Uzbek villages. In June a delegation

of Jadidists travelled to Tashkent to request military assistance to put down the rebellion. While the delegation of Jadidists were in Tashkent,

Isfandiyar's hakims persuaded the Khan to stage a coup d'état and to arrest Matmuradov and his Jadidist associates. A number of

Khivan Jadidists were subsequently put on trial.

The Turkmen raids continued into July when a troop of Orenburg Cossacks was finally ordered to intervene under the command of Colonel Zaitsev, who

had been appointed acting military commissar of Khiva. Zaitsev's forces did not reach the Khanate until early September and only then began to

conduct raids against the Yomut insurgents. Within a week or two Junaid Khan returned from exile in Afghanistan and offered his services to

Colonel Zaitsev to fight against the rival chieftains who were now in control of the Yomut rebels. Despite this surprising alliance Zaitsev made

little impact on the uprising, mainly because of the increasing insubordination of his troops. They were increasingly coming under the influence

of the local Russian garrison, which had been organized as a soldier's soviet and was becoming progressively disobedient towards its officers.

With the Khan firmly back in control of Khorezm and the Turkmen running riot, the Turkestan Committee came to the conclusion that the Khanate was

incapable of political and social modernization on its own. They decided to revert to the idea, proposed by Kuropatkin, of introducing reform under

military supervision with the installation of a Western-style constitutional monarchy. This would leave the Khan as the head of state alongside

an elected government, which would be responsible for the introduction of a package of comprehensive reforms. A Russian military commissar with

extensive powers would oversee the required changes.

The authority to introduce these important and long overdue reforms was finally sought from Petrograd in mid-September 1917, with a recommendation

that they should be approved by October. But the proposals became bogged down within the Russian bureaucracy. The decision had still not been

made when the Provisional Government was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in November.

Descent into Civil War

Within days officers from the former Imperial army formed the first White opposition forces in south-eastern Russia, cutting communications

between Tashkent and Moscow and isolating Turkestan from Soviet Russia. By March 1918 the Civil War had begun. Ural and Orenburg Cossacks took

over control from local soviets and the moderately socialist Mensheviks formed an interim government in the Volga city of Samara. By August

the whole of south-east Russia was under the control of anti-Bolshevik forces, with General Dutov in control of Orenburg. With the railway from

Central Asia effectively blockaded, and Moscow desperate for cotton supplies, camel caravans were used to ferry cotton from Khorezm to Emba.

Meanwhile in Transcaspia the local soviet had been ousted from power by anti-Bolshevik forces in Ashgabat, who then called on support from British

forces in Persia. This cut the railway line to the Caspian. The Turkestan Red Army was now fighting on all fronts, with some troops facing Dutov

on the Aktubinsk Front north of Emba, some fighting to the east in Semirechye, and the largest force trying to contain the uprising in Ashgabat,

leaving a residual force to maintain control in Tashkent. Even in Tashkent the Bolsheviks were not secure – in January 1919 the Tashkent Commissar

for War overthrew the local Soviet government and shot many of its members, creating consternation in Moscow. Local pro-Soviet forces violently

suppressed the rebellion, causing many deaths.

The extinction of the Kokand government had sent a brutally clear message to those Muslim leaders still contemplating national self-rule within

Central Asia. Resistance to Soviet rule now went underground in the form of a mujaheddin-like guerrilla movement, which the Bolsheviks

derogatorily termed the Basmachis, a term normally reserved for bandits and murderers. The first Basmachi campaign had taken place close to Kokand

in the Ferghana valley during 1918 and 1919 and moved on to Tashkent in 1920. The arrival of Enver Pasha, the former Minister of War for the

Ottoman Empire during the First World War, at the end of 1921 provided the Basmachis with some dynamic leadership for a brief period, during which

they managed to take control of both Dushanbe and Bukhara. Enver Pasha soon built up a considerable following and succeeded in defeating the Red

Army on several occasions. He established links with the Basmachis in Ferghana and with Junaid Khan in Khorezm. However his high profile campaign

was short-lived with the Bolsheviks managing to ambush Enver Pasha in the Pamirs during 1922. Even so the Basmachis maintained their campaign in the

region, continuing to embarrass the Soviets well into the mid-1930s.

In Khorezm Isfandiyar Khan reacted to news of the revolution by hunting down local Jadidists and other radicals, supported by Colonel Zaitsev and

Junaid Khan. However discipline within the Russian garrison was collapsing so Zaitsev ordered the pro-Bolshevik infantry regiments back to

Petro-Aleksandrovsk. Originally intending to spend the winter in Khiva and then to join up with Dutov's forces in Orenburg, Zaitsev decided to change

his plans. In January 1918 he left Khiva for Charjou with the intention of attacking opposition forces near Tashkent. When he encountered Soviet

troops outside of Samarkand, Bolshevik supporters persuaded his Cossacks to lay down their weapons, forcing Zaitsev to flee as a fugitive.

The Russian departure left Isfandiyar Khan's regime totally reliant on Junaid Khan, who commanded the only pro-Khivan armed forces in the Khanate.

Junaid Khan now exploited the timid Isfandiyar to increase his own grip on power. The Majlis was abolished and in May 1918 the Jadidist

leaders who had earlier been put on trial were executed. The handful of remaining Jadidists, who had since gone underground, escaped to Tashkent

to form a small revolutionary committee in exile, known as the Young Khivans.

While Isfandiyar remained the titular head of state Junaid Khan became the actual ruler of Khorezm, setting up a network of regional military

commanders and constructing a palace at his village of Bedirkent, close to Taxta. Taxes were raised, especially for the Uzbeks, who were also

forced to undertake compulsory labour service to clean the irrigation canals. All Turkmen were ordered to be available for military service under

Junaid. At the end of September 1918 Junaid Khan raided Urgench and stole money and property from the local Russian merchants and banks, arresting

some Russians in the process.

The Russian garrison at Petro-Aleksandrovsk had just been reinforced with Red Army soldiers under the command of a new Bolshevik military commissar,

Nikolay Shaidakov, who ordered Junaid Khan to release his Russian captives. Junaid Khan complied, but warned Shaidakov not to interfere in Khivan

affairs. Junaid realized that his security would be enhanced with Isfandiyar out of the way, especially as he could then rule through Isfandiyar's

more malleable and grateful brother, Sayyid Abdullah. In October he instructed his eldest son to go to Khiva and assassinate the Khan.

A month or so earlier Junaid had refused a request from Ashgabat to attack the garrison at Petro-Aleksandrovsk in order to slow down the Soviet

advance on Transcaspia – he felt that the mission was too dangerous, especially since Russian reinforcements could be quickly despatched by steamer

from Charjou. At the same time he knew that the nearby garrison posed a constant threat to his position. As autumn turned to winter navigation on

the Amu Darya became impossible and Junaid Khan made his move. Turkmen forces crossed the Amu Darya at six separate locations and laid siege to

Petro-Aleksandrovsk. There was an unexpected surprised when a steamer from Charjou managed to get through with reinforcements, breaking the siege

after only eleven days. In the following spring Russian troops returned from Charjou and defeated Turkmen forces on the left-bank of the Amu

Darya in the region of Pitnyak.

The Petro-Aleksandrovsk Soviet was keen to annex Khiva, but Tashkent needed all the troops it could find for the Transcaspian front. Instead they sent

a peace mission to Khorezm and negotiated a settlement with Junaid Khan, known as the Treaty of Taxta, which was signed on 9 April 1919. Khiva

would remain independent and would re-establish normal diplomatic relations and trade with Russia, who in turn would offer an amnesty to all Turkmen

charged with anti-Soviet activity. With Sayyid Abdullah Khan as his puppet Junaid Khan was firmly in charge of Khorezm and even issued coinage in

his own name. However relations with Russia remained difficult with Junaid reacting uncooperatively to a request to supply troops for the

Transcaspian campaign and then refusing to accept the Russian diplomatic representative sent to Khorezm in accordance with the terms of the Treaty.

The summer of 1919 also saw a revolt by a detachment of Cossacks based at Shımbay, who allied themselves with local Karakalpaks to take control of

the entire delta region, from No'kis up to the Aral coastline. When Shaidakov and his troops steamed down the Amu Darya to No'kis to put down the

revolt they were annoyed to be fired upon by Junaid's Turkmen supporters. After relieving No'kis, Shaidakov headed back to Petro-Aleksandrovsk in

fear of another Turkmen attack following the onset of winter. In fact Junaid Khan was already discussing the possibility of such an attack with

the rebels in Shımbay.

|

However for the Soviets the tide was turning. By October 1919 the European Red Army had defeated Dutov and Soviet forces from Tashkent had reached

Kyzyl Arvat in Transcaspia. Moscow had only just established a new government for Turkestan, the Commission for the Affairs of Turkestan or

Turkcommission, tasked by Lenin to rally the previously alienated Muslim masses to the Soviet cause. The focus now began to turn on the still

independent and counter-revolutionary territories of Bukhara and Khiva.

For once the smaller province of Khiva was singled out as the priority, given its outright hostility to Russia and its ongoing instability, another

revolt by Junaid's Yomut rivals having only just broken out again in Xojeli and Konya Urgench. At the same time the constant flow of disaffected

Uzbek radicals from Khiva had swollen the ranks of the Young Khivans in Tashkent from just over a dozen to a militia of around five hundred. In

November the Turkestan military authorities sent Skalov, their new military representative for Khiva, to Petro-Aleksandrovsk to organize an invasion,

just as a relief force from Charjou was extricating Shaidakov's forces from No'kis where they had been under attack by a combined force of Turkmen

and rebel Cossacks.

The Khorezm Peoples' Soviet Republic

Skalov crossed the Amu Darya on 25 December 1919 with 430 soldiers, including some leading zealots such as Faizullah Khojaev. They took Khanqa

and Urgench without a struggle, only to find themselves besieged in Urgench by Junaid Khan's troops for the following three weeks. Meanwhile

Shaidakov's army of 400 soldiers defeated the Cossack and Karakalpak rebels at Shımbay before crossing the river to take control of Xojeli, where

their numbers were swollen by rebel Turkmen forces opposed to Junaid Khan. After the fall of Konya Urgench Junaid Khan retreated to Bedirkent

to face Shaidakov's army from the north and Skalov's army to the south. After a two-day battle at Taxta, Junaid Khan escaped into the Qara Qum.

Khiva was taken on the 1 February 1920.

With the Red Army in control Sayyid Abdullah Khan, the very last Qon'ırat Khan was forced to abdicate with his power transferred to a temporary

revolutionary committee led by Hajji Pahlavan Niyaz Yusupov, a wealthy local merchant. Only a tiny minority of the Young Khivans were Communist,

yet Tashkent immediately responded to this faction's request for the establishment of a Soviet Republic in Khorezm. A political delegation was

quickly despatched to conduct elections to a nationwide congress of soviets. On 27 April the First All-Khorezm Congress of Soviets met and

agreed to abolish the Khanate in favour of an independent Khorezm People's Soviet Republic. The Young Khivans were now in control of Khorezm,

heading 10 of the 15 available departments, and with the chairman of their central committee, Hajji Pahlavan Yusupov, acting as Premier.

In September 1920 the Khorezm People's Soviet Republic concluded an extraordinary formal treaty with the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic,

which superseded all previous agreements and withdrew all former Russian claims and rights over the territory. Russia recognized Khorezm's full

independence, but offered a voluntary economic and military union and assistance with economic and cultural development, including a campaign

against illiteracy and educational resources. All property, land concessions, and rights of usage of the Russian government, Russian citizens,

or Russian companies were transferred to the new government of Khorezm without compensation. Even the assets of the Amu Darya Flotilla were

transferred to a joint Khorezmian and Bukharan river authority. Soon teachers, doctors, and military instructors arrived from Tashkent and

elsewhere with supplies and equipment. Work began to establish 35 new schools and 15 adult colleges, as well as Khorezm's first national university.

Canals were repaired, bridges were built, and the telegraph was extended.

Yet Khorezm was still polarized by the enmity between the settled Uzbek and the nomadic Turkmen populations. The Young Khivans who dominated the

government in Khiva were all Uzbeks and they wanted to see the supporters of Junaid Khan, who had seized control of the Khanate, punished. About

one hundred Turkmen were arrested and shot and others were disarmed, while punitive raids were directed against villages suspected of supporting

the Turkmen rebels. In Tashkent the Turkcommission were concerned about unfolding events and sent a team of investigators to Khiva, led by

Valentin Safonov, a former Bolshevik army commander. He was alarmed to find that the Young Khivan government had no liking for Marxist socialism

whatsoever and was doing its best to block its introduction. It had even gained control of the nascent Khorezm Communist Party.

Safonov convened an all-Turkmen Congress in Khorezm at the small left-bank town of Porsa, securing the support of the Turkmen leaders to overturn

the Young Khivan government. A mass demonstration was engineered in Khiva against that government in March 1921, providing an excuse for the Red

Army to capture the government offices and to oust the Young Khivans. A governing provisional revolutionary committee was formed, consisting of

two Uzbeks, one Turkmen, one Qazaq, and a member of the Komsomol. Elections were held to form a Second All-Khorezm Congress of Soviets, which met

in May to form a new government, devoid of Young Khivans. Many of the latter had fled into the Qara Qum to join Junaid Khan, whose following

had increased dramatically after Safonov's intervention into Khorezmian affairs.

The Russians kept a close eye on subsequent events, purging the supposedly independent government and the local Communist Party at will. In October

several members of the former government were executed or imprisoned for counter-revolutionary activities, while others were arrested during the

year-long purge that followed.

|

The Khorezm Soviet Socialist Republic

Despite the expulsion of the Young Khivans the Soviet Government remained concerned that Khorezm remained a hotbed of counter-revolution. Stalin

wanted the region transformed into a "fully socialist" society, so it was decided in 1922 that the whole of Turkestan, including Khorezm and Bukhara,

should operate as a single economic unit. The Central Asiatic Economic Council was formed to integrate all of the region's agriculture, irrigation,

post and telegraph systems, trade and monetary systems. Meanwhile Moscow took back control of the Amu Darya Flotilla. Finally the Communist Parties

of Khorezm, Bukhara, and Turkestan were merged with the Communist Party of Russia, under the supervision of the Central Asian Bureau or Sredazburo,

of the Central Committee.

During the 10th All-Russian Congress of Soviets in December 1922, Stalin referred to the problem in Khorezm:

"Two independent Soviet Republics, Khorezm and Bukhara, which are not Socialist Republics but Peoples' Soviet Republics, remain for the time being outside the union solely and exclusively because these republics are not yet socialist. I have no doubt, comrades, ... that as they develop internally towards socialism, these republics will also join the union state which is now being formed."The Russian Central Committee sent a senior hard-line Bolshevik to Khiva to conduct a ruthless purge of the local party and the government. The membership of the Khorezm Communist Party was reduced from a few thousand to a few hundred, with the expulsion of all merchants, tradesmen, and landowners. Following the purge the 4th All-Khorezm Qurultay of Soviets changed the constitution of Khorezm on 20 October 1923 to disenfranchise "all non-toiling elements". Restyled the Khorezm Soviet Socialist Republic, Khorezm had finally qualified as a "socialist" republic and now formally requested membership of the USSR.

"Muslims of Russia, Tatars of the Volga and the Crimea, Kyrgyz and Sarts of Siberia and Turkestan, Turks and Tatars of Transcaucasia, Chechens and Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus, and all you whose mosques and prayer houses have been destroyed, whose beliefs and customs have been trampled on by the Tsars and oppressors of Russia. Your beliefs and usages, your national and cultural institutions are forever free and inviolate. Organise your national life in complete freedom. This is your right. Know that your rights, like those of all the peoples of Russia, are under the mightly protection of the Revolution and its organs, the Soviets of Workers, Soldiers, and Peasants."Finland was the first part of the Empire to declare its independence after the revolution and it was followed in the first quarter of 1918 by the Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Meanwhile Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were encouraged to declare independence after their occupation by Germany. In July 1918 the Bolsheviks established the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic, or RSFSR, with its own constitution based on a free federation of independent nations.

|

The policy was soon reversed. Finland had immediately become immersed in civil war, while the Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan came under

the control of unfriendly anti-Bolshevik governments. However within a few years a combination of military and political intervention soon brought

these errant nations back into the Soviet fold, except for Finland. From now on nations would only be allowed to exert self-determination after they

had first become Communist.

There were more practical issues to consider. Turkestan and the Steppe Region had become home to about 2 million Russian immigrants who wanted to

remain an integral part of Russia. The region had huge natural resources and the Bolsheviks had no desire to leave this vast region open to

British Imperialist interests. There was also increasing concern about the potential challenge that could emerge if the various Muslim territories

of Central Asia should unite to form a pan-Islamic State. By early 1919 the new regime had dropped any idea of independent nation states, let alone

Muslim states, in Central Asia.

Lenin and the Central Committee wanted to establish an administrative structure and constitution for the new Bolshevik State. Although Marx had

argued that nation states would disappear as workers united across international boundaries, the government of such a huge ethnically and

linguistically diverse territory was unthinkable without strong provincial subdivisions. Lenin had promised "self-determination for the toilers"

and he intended to deliver this through his new nationalities policy, by transforming the RSFSR into a federation of national states that would no

longer be independent but would be "partially autonomous". The first attempt at such a structure was a failure, with the administration in Moscow

riding roughshod over the terms of the various bilateral treaties. Following complaints from the Communists of the Ukraine and Georgia, the Central

Committee of the RSFSR established a constitutional commission under Stalin.

Lenin was concerned about potential Russian ethnic domination and wanted a federation in which all nation states were equal. However Stalin believed

that the Russian government in Moscow should hold a pre-eminent position. The onset of Lenin's illness in 1922 had meant that three old-time

Bolsheviks, Zinoviev, Kamenov, and Stalin became the de facto ruling triumvirate of the USSR, effectively in control of the Politburo.

Stalin, who had just been promoted to the post of General Secretary of the Russian Communist Party in April, increasingly took control of

constitutional and nationality affairs. Stalin's initial proposal would have extended the power of the RSFSR over the so-called autonomous

republics, but was rejected by Lenin because it conflicted with his vision of a federal state and gave pre-eminence to Russia.

The compromise was the proposal to form a Union of Soviet Socialist Republics governed by a newly formed Central Executive Committee. This would be

composed of representatives from the Central Executive Committees of the member Republics. The supreme legislative body would be the Congress of

Soviets of the USSR, and its highest executive body would be the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR. The Union Republics would have their

own Commissars for finance, supply, agriculture, education, health, etc. and these would be subordinated to the corresponding agencies at

federal government level. The ratification of the Union Treaty on 30 December 1922 joined the RSFSR to the Ukraine, Belarus,

and the Transcaucasus to form the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or USSR. The Turkestan ASSR remained a component part of the RSFSR. The

Central Executive Committee of the USSR formally approved the Constitution of the USSR on 6 July 1923.

Lenin had already written to the Communist Party in Tashkent in 1919, asking them to investigate how many national republics should be established

in Turkestan and how they should be named. A Turkcommission was dispatched from Moscow headed by General Mikhail Frunze and Kuybishev to oversee

the current and future governance of the region. They discovered that the chauvinism of the Tashkent Bolsheviks had set local Muslims against the

revolutionaries in Moscow. The Muslim Communists wanted Turkestan to gain more autonomy as a Soviet Republic of Turkic Peoples, with its own Turkic

Red Army. However Frunze believed this was a petit bourgeois idea. He argued that Turkestan should be divided along ethnic lines, between

the Uzbeks, Turkmen, and Qazaqs. He told Lenin that the main obstacle would be a shortage of reliable native leaders. Lenin was disturbed by the

situation in Turkestan and instructed the Turkcommission to take a softer approach in order to win the support of the local population. While in

Tashkent Frunze conducted a purge among the local Russian Communists.

However Frunze's conclusion was disputed by local activists led by Ryskulov, subsequently labelled "deviationists", who submitted counter-arguments to

the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party. They argued that the land in Central Asia tended to alternate from strips of steppe and

semi-desert suitable for nomadic pasturage to strips of alluvial land suitable for cultivation, making ethnic division problematic. Furthermore

the perceived ethnic differences in Turkestan were superficial since different ethnic groups could communicate with each other in a common dialect

within each region. Division would not only raise local sensitivities but would cause problems with long distance nomadic migrations, the management

of water, timber, and fish resources, inter-ethnic trade, and rail and telegraph communications. It would also create problems for ethnic minorities

such as the Tajiks, Karakalpaks, and Dungans.

Lenin and the Politburo considered the issue on four occasions during 1920 and finally came down in favour of the ethnic division of Turkestan.

Lenin asked for a detailed plan of how the separation would be made along with a map of the territorial reorganization. The biggest challenge was

how to divide the Soviet Peoples' Republics of Khorezm and Bukhara and this would require a detailed analysis of communications and resources such as

water, grazing pastures, land under cultivation, forests, and fishing. However little could be done on the ground until the governments and

Communist parties of Khorezm and Bukhara had been purged of local activists and filled with Soviet stooges. The formation of the puppet states of

the Khorezm SSR in October 1923 and the Bukharan SSR in September 1924 paved the way for implementing the new policy.

The Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast

Lenin died in January 1924, missing the ratification of the new Constitution of the USSR by the Second All-Union Congress of Soviets by ten days.

At the end of the month the Orgburo discussed Turkestan delimitation again. In April the matter was discussed at the Politburo and the Sredazburo

was tasked with the job of drawing up detailed proposals. Within weeks the Sredazburo set up local commissions through the Communist Parties of

Turkestan and Bukhara along with a Central Territorial Commission of its own, which in turn established Uzbek, Qazaq, and Turkmen sub-commissions.

The latter were responsible for defining the new national borders, designating capital cities, cultural and economic centres, and autonomous

oblasts. There was also a Khorezmian delegation and technical commissions were formed to resolve some of the more complex issues.

The whole matter was highly political and led to a great deal of local campaigning and agitation by the interested parties involved. Despite the

massive purge of the Khorezm Communist Party, the Executive of its Central Committee formally decided in March 1924 against an ethnic division of

Khorezm. At the same time some Karakalpaks could not see a future for their own ethnic minority in a divided Turkestan and argued for the Amu Darya

Division to be added to the Khorezm SSR.

The shorthand reports of the Central Territorial Commission are now available to researchers although some of the technical reports still remain

secret. They illustrate the difficulties faced by those involved and of the lack of consensus among the different commissions. Although the Uzbek

and Turkmen sub-commissions supported delimitation, the Khorezmian delegation fought hard to preserve the unity of its region, while the Qazaq

sub-commission supported the idea of a Soviet Central Asian Federation. The Uzbeks initially chose Samarkand as a capital, so the Qazaqs

recommended that Tashkent should be their capital city. These conflicts were resolved at Sredazburo level and some decisions required trade-offs

while others were undoubtedly influenced by the political ambitions of those involved. Some territories were deemed too small and were expanded

at the expense of their neighbours. Thus the Uzbek territories of Dashoguz, Chardjou, and Kelif were classified as Turkmen. Moscow clearly favoured

ethnic separation and saw this as a means of ending long-term feuds such as those between the Turkmen and Uzbeks.

The basic concept was that each new "nation state" would become a Soviet Socialist Republic, or SSR, with its own constitution, its own legislative,

executive, judicial institutions, and its own party structure. Each would be named after its largest ethnic population and would become members

of the USSR. Ideally an SSR should have at least one international border. Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republics, or ASSRs, would have some degree

of autonomy but would be subordinate to an SSR. Each SSR would be divided into provinces or oblasts.

The Sredazburo considered the sub-commission reports in May and resolved the following:

- to form Uzbek and Turkmen SSRs as part of the USSR,

- to form a Tajik Autonomous Oblast within the Uzbek SSR,

- to form a Kara-Kyrgyz (Kyrgyz) Autonomous Oblast within

a Republic yet to be decided,

- to transfer the Kyrgyz (Qazaqs) living in Turkestan to the

Kyrgyz (Qazaq) ASSR.

The Kyrgyz (Qazaq) ASSR had been previously formed within the RSFSR on 1 September 1920. Note that at that time the Qazaqs were referred to as

Kyrgyz and the Kyrgyz were referred to as Kara-Kyrgyz.

The issue regarding the possible formation of a Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast was still unresolved. These conclusions were endorsed

by the Politburo in June with one exception – the Khorezm SSR would be preserved as the one and only heterogeneous republic in Central Asia.

By 26 July the Khorezm Communist Party had been purged again of its "bourgeois-nationalist" elements. Under pressure it reviewed its recent

"mistaken" decision and now voted in favour of the delimitation of Khorezm. The Politburo was asked to reconsider the case and decided in favour

of ethnic division. In the same month the Turkestan ASSR transferred the island of Moynaq from the Syr Darya to the Amu Darya Division.

Following a resolution of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party the Sredazburo agreed that Central Asian delimitation should be

completed by October.

The Central Territorial Commission decided on 21 August 1924 in favour of creating a Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast from parts of the

Khorezm SSR and the Amu Darya Division. It was left to the sub-commissions to decide how the borders of the proposed Kyrgyz (Qazaq), Uzbek, and

Turkmen SSRs would need to be modified. Meanwhile a temporary Karakalpak sub-commission was tasked with delineating borders and starting a local

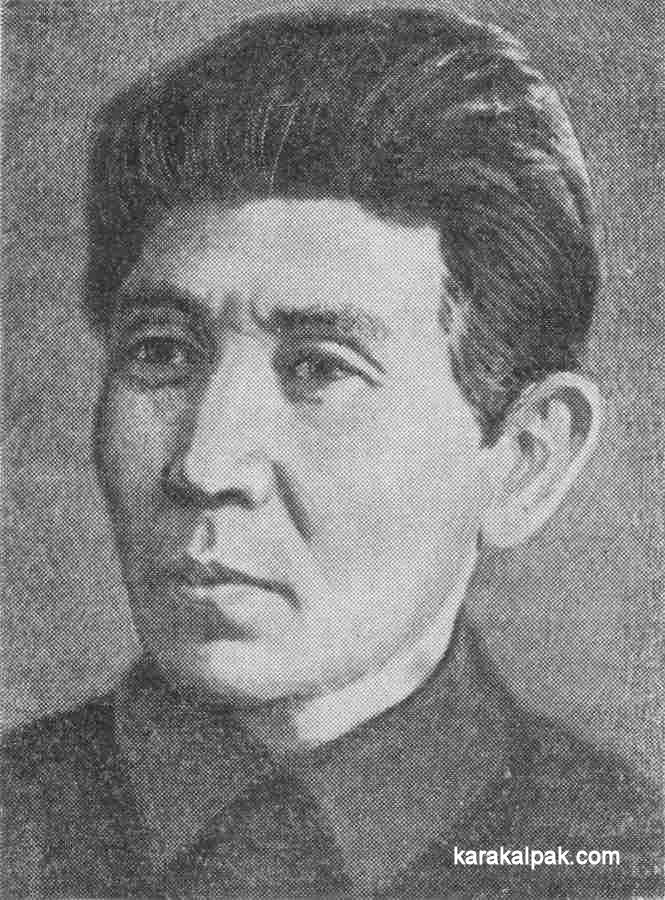

propaganda campaign. Its Chairman was Allayar Qorazovich Dosnazarov, a one-time shepherd from Kok-ozek who had worked his way up the Party ladder

and had been sent to the East Moscow Communist University from 1921 to 1923. Meetings were organized in the towns and rural districts of Shımbay

and Shurakhan sections. In Shımbay there were Uzbek protests over the possibility of rule by Qazaqs and Karakalpaks.

|

On 5 September the Plenum of the Regional Committee of the Amu Darya Division informed the Central Territorial Commission that the Karakalpak

Autonomous Oblast would need to be formed from the Amu Darya Division itself, plus the Qon'ırat and Xojeli regions and the Qıtay and Qıpshaq

sections of the Khorezm SSR. The Central Territorial Commission agreed that the Shımbay section of the Amu Darya Division should be transferred to

the Karakalpak region but that the Shoraxan section should go to the Uzbek section. It was left to the Sredazburo to recommend that the Karakalpak

Autonomous Oblast should include all of the Shoraxan section, apart from the district of Man'gıt, which should be transferred to the Uzbek SSR.

The Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast would form part of the Kyrgyz (Qazaq) ASSR, itself a part of the RSFSR.

A special extraordinary session of the Turkestan Central Executive Committee convened on 15 September 1924 to discuss and approve the plans for

the national and territorial delimitation of Central Asia. Within a few weeks these had been ratified by separate All-Bukharan and All-Khorezm

Qurultays of Soviets. They were finally adopted by the Bolshevik Central Executive Committee of the RSFSR on 14 October, but with a number

of amendments. The Tajik Autonomous Oblast became the Tajik ASSR incorporated within the Uzbek SSR, the Kara-Kyrgyz (Kyrgyz) Autonomous

Oblast was included within the RSFSR, and the Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast was included in the Kyrgyz (Qazaq) ASSR. On 27 October

the 11th Convocation of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR sanctioned the change at its second session in Moscow. It was not until

11 May 1925 that formal approval to the division of the Turkestan ASSR was given at the 12th All-Russian Qurultay of Soviets.

The Presidium of the Qazaq Central Executive Committee authorized the transfer of the Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast into the Qazaq ASSR

on 17 October, making way for the formation of a revolutionary committee to temporarily govern the new Karakalpak Oblast. Meanwhile a

liquidation committee, Likvidcom, was established to allocate livestock, cultivated land, and business assets between the newly delineated republics

and oblasts. Thus for example the Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast was allocated 380,745 cattle.

The First Constitutive Congress of the Soviets of the dekhans, seamen, and Red Army deputies of the Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast

was held in its new capital, the city of To'rtku'l (Petro-Aleksandrovsk prior to the revolution), from 12 to 19 February 1925. This resulted in

the formation of an Executive Committee and the selection of 40 delegates to attend the forthcoming All-Qazaq Qurultay of Soviets. Decisions

were made concerning Karakalpak administration, education, economic, and agricultural development including a planned expansion of cotton growing.

The Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast was divided into four regions and twenty six rural districts:

| Region | Districts |

|---|---|

| To'rtku'l | Biy-Bazar |

| Sarı-biy | |

| To'rtku'l | |

| Sheik-Abbaz-Valiy | |

| Ming-bulak | |

| Tamdı | |

| Shoraxan | |

| Shımbay | Da'wqarin |

| Kegeyli | |

| Kok-O'zek | |

| Qon'ırat | |

| Na'wpir | |

| No'kis | |

| Taldıq | |

| Shımbay | |

| Yani-Bazar | |

| Xojeli | Qarateren' |

| Qıpshaq | |

| Qıtay | |

| Lauzan | |

| Miskin-Atin | |

| Xoja-Yarmish | |

| Qon'ırat | Kyuzyl-Yar |

| Xaniyab | |

| Moynaq | |

| Toqmaq-ata |

|

It was against this background that attention increasingly focused on the underperforming regions of the USSR, including the Karakalpak Autonomous

Oblast. Its incorporation into what had now become the Qazaq ASSR had been a disaster. The Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast not

only lacked the skilled technicians required to develop its agricultural, livestock, and fishing industries, but also the educational resources to

train them. It had gone from a backwater of the Russian Empire to a backwater of the Qazaq ASSR, located 1500 km to the west of Alma-ata and not

even connected to Kazakhstan by road. Since its creation little had been done to modernize its agricultural economy. A few cooperatives and machine

hire centres had been established but most farms remained under the control of beys and the clergy. In 1928 the Karakalpak Oblast

had only 3 tractors, 83 ploughs, 79 harrowers, and 62 seeders. Collectivization began in the second half of 1928, but by the end of the following year

the total number of kolxoz had only reached 33. The achievement of the targets laid down in the First Five Year Plan demanded more

radical changes.

On 20 July 1930 the Presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee approved the decision to remove the Karakalpak Autonomous

Oblast from the Qazaq ASSR and to include it directly within the Russian Federation. Russian technocrats were sent to Karakalpakia

from Moscow, Leningrad, and Ivanovo to investigate the reasons for its sluggish economic performance. They concluded that the region suffered from

a weak technical infrastructure for its agricultural industries, it had an insufficiently developed irrigation network, collectivization was not

proceeding fast enough, the administration and targeting of the collective and state farms that it had was not properly organized, transport was

inadequate, there were labour shortages, and the organization and management of provincial and district government was poor.

The Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR considered a report on the region on 1 August 1931 and agreed to a number of its recommendations.

These included a major expansion in the Shımbay irrigation system, an increase in the cotton acreage, a new state rice farm, a cotton cleaning plant,

four new agricultural machinery depots, a hydro-electric station, an major expansion of technical education to increase the number of veterinary,

irrigation, and fishing specialists, and a new pedagogical institute. There would also be a new print works in addition to an expansion of the existing

printing house in To'rtku'l in order to increase the amount of technical literature available in the Karakalpak language.

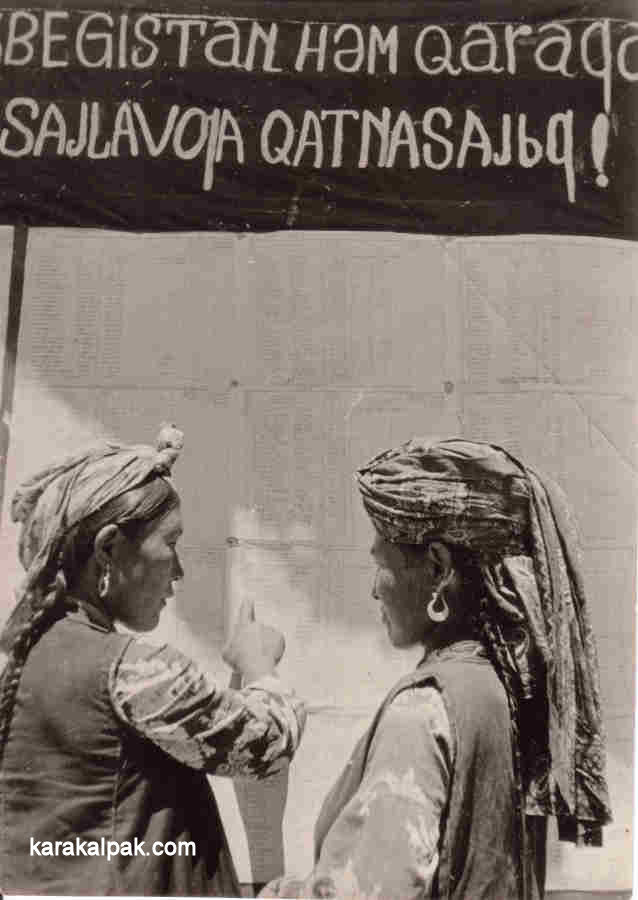

As agricultural collectivization progressed during the crucial years of 1930 and 1931, it placed an enormous burden on local administrators and

officials. A massive programme was initiated across the RSFSR to re-elect and strengthen local soviets, removing those who might oppose collectivization

in favour of loyal supporters. After the 1930-31 elections to the Karakalpak Qurultay of Soviets, 122 of the 192 deputies were Communist Party

members and 45 were women. The initiative also led to an increase in Karakalpak Communist Party membership, which exceeded 4,000 during 1932.

Inadequacies in Karakalpak local government and administration led to calls for the region's status to be elevated from an Autonomous Oblast

into an Autonomous Republic. The Executive Committee of the Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast considered the matter and issued a recommendation

to the Central Executive Committee of the Russian Communist Party that such a conversion would support a speeding up in the reconstruction of the

Karakalpak economy.

An emergency meeting of the Executive Committee was held on 5 March 1932. After considering the prospects for the future development of

Karakalpakia it was decided to place a petition in front of the Presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. The Presidium met on

20 March 1932 and agreed that the region should be converted to the Karakalpak Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within its existing boundaries.

It would now become a federal member of the RSFSR. The First Qurultay of Soviets of the Karakalpak ASSR would be responsible for electing

the Central Executive Committee and for organizing the new apparatus of state in accordance with the constitution of the USSR. This took place

two months later on 25 May 1932 in To'rtku'l. In addition to the Central Executive Committee, the Qurultay established a Council of

Peoples' Commissars. Peoples' Commissariats were formed for justice, education, public health, social welfare, light industry, agriculture,

municipal services, labour, supply, finance, and peasant and worker inspection.

|

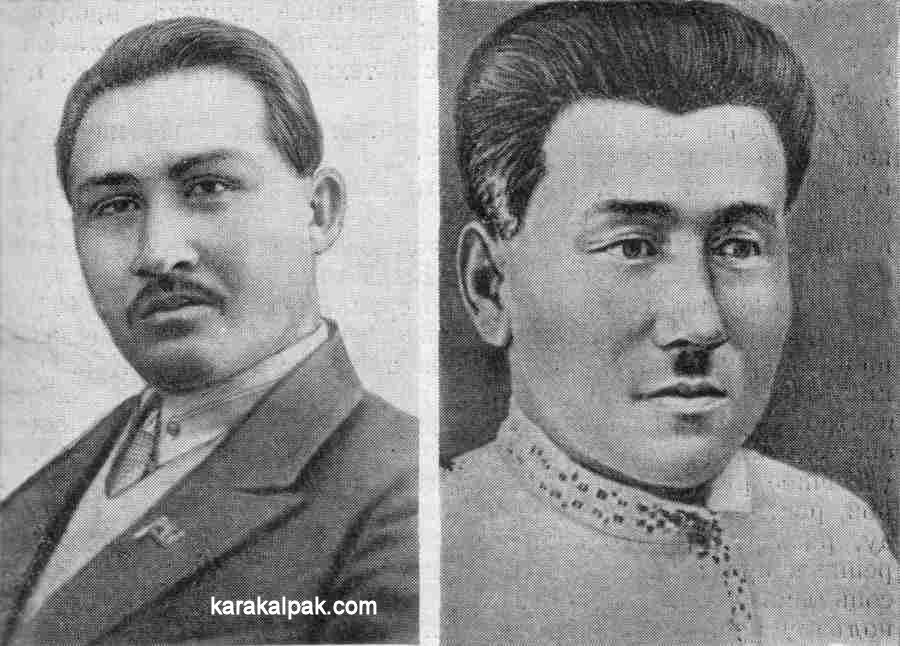

The first session of the Central Executive Committee was convened on 30 May 1932. Ko'ptlew Nurmukhamedov was appointed as its first Chairman and

Qasım Avesov became the Chairman of the Council of Peoples' Commissars of the Republic. Nurmukhamedov only lasted for two years, Avesov becoming the

Karakalpak leader in 1934.

|

Entry into the Uzbek SSR

The first half of the 1930s saw unprecedented changes throughout Karakalpakia. Owners of land and livestock, including the clergy, had their

property confiscated, and those who refused to cooperate were exiled to Siberia camps and their sons were conscripted into the Red Army, often

never to be seen again. There was widespread resistance, some of it organized, with bays attempting to influence village soviets and

to intimidate officials. The implementation of collectivization seems to have progressed relatively smoothly for ordinary peasants and workers,

many of them glad to be rid of their oppressive landlords. Most of the people inhabiting the delta lived within extended families that were essentially

already operating as a collective unit, and the collectivization process involved little more than combining several family groups belonging to

the same clan into a single economic unit. Two types of farm appeared: the state farm, or sovxoz (short for sovetskoe khoziaistvo)

and the more common collective farm, or kolxoz (short for kollektivnoe khoziaistvo). The fishermen at Moynaq were also organized

into kolxoz, and industrial activities were nationalized and organized into artels.

Enormous pressure was applied to the new collectives to plant cotton, pressure that they resisted because the price for cotton was low. Even so the

output of cotton doubled during the First Five-Year Plan (1928-32), as did the area of land under irrigation. At first political commissars were

assigned to the collectives to ensure compliance but then, in 1934, cotton prices were raised by 500%. Cotton immediately became highly attractive,

being referred to as "white gold" and the cotton acreage soon increased. Now the challenge was to raise cotton yields and this was achieved by

the increasing application of mineral fertilizers from 1935 onwards.

The economy benefited from an influx of skilled workers and technicians, ranging from tractor drivers to agronomists and accountants. The number of

kolxoz reached 500 at the end of the First Five-Year Plan and 1,000 by the end of the Second. For the first time in many generations

ordinary people began to see significant improvements in their standard of living, education, and welfare.

|

There were also changes to the boundaries of the Karakalpak ASSR in 1935, with agreement over a new border between the Qıpshaq and Xojeli regions

and the Kalinin and Konya Urgench regions of the Turkmen SSR, and the delineation of the Karakalpak and Qazaq regions of the Ustyurt and Aral Sea.

Ironically in Moscow work was progressing on the drafting of a new Constitution of the USSR, just as Stalin was embarking on his reign of terror and

laying the foundations for a completely totalitarian state. The USSR was to become a democratic federation of eleven Soviet Socialist Republics,

any of which could leave the union if it so wished. It included Russia and the five Central Asian Republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan,

Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. It was clear that it no longer made sense to include the Karakalpak ASSR as a part of the Russian SSR. The two were

not physically linked other than by air, and the cotton-based economy of Karakalpakia was more like that of its neighbouring Republics. The Uzbek

SSR had the agricultural and industrial base to provide support for Karakalpakia and was well connected to it by road, rail, and river. It also

had the political resources to assist its neighbour in the building of its government and Communist Party structure.

The idea of transferring the Karakalpak ASSR to the Uzbek SSR was very attractive to politicians in Tashkent, since it would greatly extend the

size of their country and increase its agricultural and mineral resources, particularly the Aral fishing industry and the Qara Qum gold deposits.

Uzbek officials persistently lobbied the Kremlin to gain support for the move.

The so-called Stalin Constitution was introduced in November 1936, although few people took it seriously. It was approved by the Eighth

Extraordinary Congress of Councils of the USSR on 5 December 1936, thus formally transferring the Karakalpak ASSR to the Uzbek SSR.

On 12 February 1937 the Sixth Extraordinary Congress of Councils of the Uzbek SSR approved the new Uzbek Constitution. The new Constitution

of the Karakalpak ASSR was approved by its own Congress on 23 March 1937. On paper it granted all of its citizens full democratic freedoms and

rights, independent of nationality or race.

|

Elections for the Central Committee were held in Karakalpakia on 6 December 1937. There were no competing candidates - one member of the Communist

Party stood for each position. V. A. Khomutnikov became the Chairman of the Central Executive Committee and the following year took on the new title

of President of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Karakalpak ASSR, a position he maintained until 1947. Jumbay Kurbanov remained Chairman of

the Council of People's Commissars.

Post Script

Critics of Tsarist imperialism were obliged to support the concept of self-determination. However Lenin and Stalin's endless writings about the

subject suggests it was an issue they were never really comfortable with. Yet their acceptance of the independence of Poland, Finland, and the Ukraine

after the October 1917 coup d'état shows that they genuinely supported a policy of national independence at that time.

Marxist historical theory had predicted that the unity of nation states was an inevitable consequence of revolution. Once in power, Lenin and Stalin

had to rapidly modify their beliefs in the face of political realities. Unity was only achievable through military might and the concept of autonomy

became a convenient means of creating the illusion of self-determination within an increasingly totalitarian system.

Stalin had accepted the Marxist idea that history would inevitably lead to ethnic separation and incorporated such views in his writings, elevating

them to the status of scripture. But Stalin was more down-to-earth than Lenin and saw the political benefits of an ethnic delineation: the ability

to "divide and rule" regional states, the creation of barriers to Turkic or Islamic unification, the elimination of ethnic conflict, and the

opportunity to create the illusion of self-determination.

The practical arguments of Ryskulov counted for little in the face of the overwhelming desire of the Soviet leadership to control and unify a vast

and diverse empire recently torn apart by civil strife.

In the end the territorial division of Central Asia was badly conceived, badly planned, and badly rushed. Even the Chairman of the Sredazburo,

Zelenskiy, admitted that the work was "done with an axe". Yet given the ethnic mosaic of Central Asia a perfect division along ethnic lines was

impossible. The task of ethnically dividing up Turkestan was something like the equivalent of trying to divide up a multi-ethnic country like

Afghanistan today. The idea of ethnically defined nations with fixed borders was quite alien to the essentially tribal people who lived there,

whose identity was based on family and clan ties and whose concept of territory was linked to their oasis, farm settlement, or pasturage. When

the Bolsheviks sought advice from the renowned Orientalist Vasiliy Barthold he told them that the idea ran contrary to historical experience and

would be a great folly.

The outcome made it difficult to coordinate the water management, land use, and communications of the lower Amu Darya region. Instead of being

separated into three Khanates the Uzbeks found themselves spread across six new administrative territories, with important enclaves in northern

Turkmenistan, southern Karakalpakstan, and southern Kazakhstan. Meanwhile the allocation of the Tajik cities of Bukhara and Samakand to the Uzbek

SSR divided the Tajik population. At least the subsequent reunification of Karakalpakstan and Uzbekistan has gone some way to repair the damage.

|

The real problems of ethnic delineation have only fully emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The fragmentation of Central Asia into

independent but insecure Republics, each jealously guarding their new international borders has created a travesty for the region. The major

problem for the Khorezm oasis region is its partitioning into isolated Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan halves. Communications have been disrupted;

families divided; markets fragmented; regional trade paralyzed. Smuggling has become the main growth industry. If one example alone is enough

to illustrate the current madness it is the need for Uzbekistan to develop a self-contained railway system in order to avoid the delays and

taxation incurred through the use of the established direct lines through Turkmenistan.

References

Allworth, E. A., Central Asia, a Century of Russian Rule, Columbia University Press, New York, 1967.

Allworth, E. A., The Modern Uzbeks. From the Fourteenth Century until the Present, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, 1990.

Babushkin, L. N., Soviet Uzbekistan, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1973.

Badretdin, S., Pan-Turkism: Past, Present and Future, Turkoman Magazine, London, December 1998.

Becker, S, Russia's Protectorates in Central Asia: Bukhara and Khiva, 1865 – 1924, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1968.

Blank, S., The Sorcerer as Apprentice: Stalin as Commissar of Nationalities, 1917-1924, Westport, Connecticut, 1994.

Carrère d'Encausse, H., The Great Challenge: Nationalities and the Bolshevik State, 1917-1930, Holmes and Meier, New York, 1992.

Deutscher, I, Stalin, A Political Biography, Pelican Books, 1966.

Dosumov, Ya. M. and Ametov, K. A., The national demarcation of Central Asia and the formation of the Karakalpak autonomous region, Chapter 4, History of the Karakalpak ASSR, Volume 2, Fan Publishing House, Tashkent, 1986.

Dosumov, Ya. M. and Bekimbetov, A., Karakalpakia in the period of socialist industrialization and agricultural collectivization (1926-1932), Studies in the History of the Karakalpak ASSR, Volume 2, Chapter 4, Nauka Publishers, Tashkent, 1964.

Khalid, A., The Politics of Muslim Cultural Reform: Jadidism in Central Asia, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1998.

Lansdell, H., Russian Central Asia, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1885.

Maillart, E. K., Turkestan Solo, translated by John Rodker, G P Putnam's Sons, New York, 1935.

McCauley, M., The Russian Revolution and the Soviet State 1917 – 1921, Documents, The Macmillan Press, London, 1975.

Nutmukhamedov, M. K., Muminov, I. M., and Dosumov, Y. M., History of the Karakalpak ASSR, Volume 2, Fan Publishing House, Tashkent, 1986.

Paksoy, H. B., Nationality or Religion?: Views of Central Asian Islam, AACAR Bulletin of the Association for the Advancement of Central Asian Research, Volume 8, Number 2, Autumn 1995.

Pierce, R. A., Russian Central Asia 1867-1917, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1960.

Pipes, R., The Formation of the Soviet Union: Communism and Nationalism 1917-1923, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1997.

Rahimov, M., and Urazaeva, G., Central Asian Nations and Border Issues, Conflict Studies Research Centre, Defence Academy of the UK, Camberly, 2005.

Rashidov, S., Soviet Uzbekistan, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1982.

Schuyler, E., Turkistan, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, London, 1876.

Skrine, F. H. B., and Ross, E. D., The Heart of Asia, Methuen and Co., London, 1899.

Smith, J., The Bolsheviks and the National Question, 1917-1923, Macmillan, London, 1999.

Tatybaev, S. U., The Victory of Socialism in Karakalpakia (1933-1937), The Karakalpak ASSR in the period of the completion of the socialist reconstruction of the national economy, Studies in the History of the Karakalpak ASSR, Volume 2, Chapter 5, Nauka Publishers, Tashkent, 1964.

Tatybaev, S. U., Formation of the Karakalpak ASSR, Chapter 7, History of the Karakalpak ASSR, Volume 2, Fan Publishing House, Tashkent, 1986.

Treadgold, D. W., Twentieth Century Russia, Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado, 1995.

Von Laue, T. H. and A., Faces of a Nation - The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991, Fulcrum Publishing, Colorado, 1996

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

|

This page was first posted on 17 July 2006. It was last updated on 27 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |