The Mongols

|

The Mongols

|

|

ContentsThe Eastern Nomadic TribesThe Rise of Chinggis Khan Mongol Unification The Qara Qithay Mongol Expansion in the East Relations with Khorezm The Conquest of Khorezm Ghaznia, Khurasan, the Caucasus and Qipchaq The Ulus of Jöchi Conclusions Appendix 1. Historical Sources Appendix 2. The Early Mongol Tribes and Clans Appendix 3. Chinggis Khan's Chief Sons, Grandsons, and Generals References The Eastern Nomadic TribesThe Mongol confederation that dominated Central Asia and Eastern Europe for much of the 13th and 14th centuries was initially formed from a large number of nomadic tribes who roamed across a massive region stretching eastward from the Altai across Mongolia and south-eastern Siberia. It involved people from three linguistic groups: Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic; encompassing pastoral steppe nomads in the south and forest-dwellers in the north.Little is known about the origin of the Mongolic-speaking tribes. They descended from the Hsien-pi, one of the many northern tribal confederations that the 5th century Chinese Hou Han-shu (History of the Later Han Dynasty) called the Tung-hu or Eastern Barbarians. We know that in approximately 90 AD the Hsien-pi absorbed some of the northern Hsiung-nu. By the late 3rd century two of the Hsien-pi leaders had already adopted the title qaghan, possibly suggesting a link with the neighbouring Turkic tribes to their west. It is possible that the Mongolic-speaking people were originally hunters and fishermen who only became nomadic pastoralists after absorbing some of the Turks who lived in the area now known as Mongolia at the end of the 10th century. Even so it is obvious from their later lifestyle that hunting continued to play an important role in their activities.

Even today much of Mongolia remains a wilderness of wide open pastures.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The most powerful neighbouring nomadic federations at this time were:

|

Other important Mongol groups in the region included the Onggirats, who lived close to the Tatar in the Qalka river region in the extreme east of

Mongolia, and the Oyirat or Dörben Oirad ("Allied Four"), a group of four forest tribes located to the west of Lake Baikal. Further afield

lived the Qyrgyz or Kyrgyz, a Turkish tribe in the upper Yenisey; the Uighurs, Turkish nomads and settlers north-east of the Tarim Basin; the

Ongut, or Önggüd, Turkish nomads living south of the Gobi desert; and finally the Solang, a Tungusic tribe living in the northern part

of Manchuria.

The only sedentary state with any power in the region was the Chin or Jin (meaning gold) dynasty, founded by the Jürchids, one of the Tungusic

tribes that had taken control of Manchuria from the Kitan in the early 12th century. The south-east of China, including the whole Yangtze basin, was

then ruled by the Sung dynasty. The Chin and the Sung had both been weakened by almost constant warfare with each other. The Chin frequently

attempted to defend their western borders from barbarian attack by forming alliances with some of the weaker nomadic groups. To the immediate south

of the steppe lay the state of Xi-Xia, founded by the Tibetan Tanguts, important traders who controlled the important Kansu oases along the eastern

arm of the Silk Route and did not generally interfere in steppe politics.

|

The two traditional enemies of the Mongols in the early 12th century were the Tatars and the Merkits, who frequently formed alliances against them.

Fearing their growing strength, the Chin launched an attack on the Mongols in 1137. Following numerous successful Mongol counter-attacks, the Chin

finally agreed to a peace treaty in 1147. This left the Mongols free to attack their other main enemy, the Tatars. "The Secret History" records that

the Mongols fought 13 unsuccessful battles against the Tatars, which led to internal Mongol divisions and finally a civil war. Much weakened, the

Mongols were finally crushed by the Chin, who had formed an alliance with the Tatars, in 1161. The Mongols were forced to pay tribute to the Chin and

became increasingly poor. Some Mongol clans became vassals to the Tatars or else allied themselves to the Kereyit. The only independent Mongols

remaining consisted of just two clans: the Tayichi'ut and the Borjigin.

By the late 12th century the traditional system of tribal organization among the pastoral Mongol nomads had collapsed. Pastoral communities had

been previously organized by clan according to common bloodline, each clan not only owning its cattle collectively, but roaming collectively as a

küriyen, a name meaning "circle" derived from the tradition of erecting yurts or gers in a circle. The development of private

cattle ownership led to a new stratification of society, with wealth increasingly concentrated in the hands of the noyad or nobles. As clans

became divided the private cattle-owners preferred to roam in smaller groups known as ayil (from which the term aul or

awıl derives). With an increasing number of ayil competing for scarce grazing resources, inter-tribal feuds became more

common, motivating ayils to join together to form larger groupings known as aymaks, under the supremacy of a leading family clan and

a single elected Khan. However tribal alliances were fickle and were frequently realigned. Some tribes were even divided between two confederations,

in effect hedging their bets.

The Rise of Chinggis Khan

Like their neighbours, the original Mongols were shamanists and animists. The tribal shaman was an important figure, on a par with the tribal leader.

Although the Mongols believed in a plethora of natural spirits they also believed that the world was controlled by a single unifying force, which they

called Köke Möngke Tengri or the Eternal Blue Heaven. They practiced exogamy, and bridal kidnappings were common, as was polygamy.

Following the death of the father, his estate passed to the youngest son of the most senior wife.

Temujin, who would later be renamed Chinggis Khan, was born into the Kiyat lineage of the Borjigin clan. His date of birth was probably between 1155

and 1167, although several recent scholars such as de Hartog and Onon believe it was more precisely 1162. If correct this was just after the defeat

of the Mongol confederation. It was the start of a period of enslavement, impoverishment, and increasing lawlessness for the majority of the Mongol

tribes. Temujin was the first-born and had three younger brothers and a younger sister. His father Yisügei was the ba'atur or chief of

the Kiyat and a blood-brother or anda of Toghrïl Khan, leader of the Kereyit, one of the largest confederations in Mongolia. On the death

of his father Toghrïl had killed his brother to become the head of his tribe, but had been quickly deposed by his uncle and forced into exile.

Yisügei had assisted Toghrïl to overthrow the uncle and to regain his throne.

|

Temujin's rise to power is outlined in "The Secret History" in a simple and far from complete manner. Apparently the Borjigins frequently selected

their brides from the Onggirat nomads living south-east of Buyr Lake in the Khölön Buyr area. At the age of 9, Temujin's father arranged

for him to be married to a 10-year-old girl named Börte from this very same tribe (later to be known as the Qon'irat). As he was returning from

the Onggirat, Temujin's father was poisoned by Tatars, the arch enemy of the Borjigins. The young orphan Temujin was appropriately considered too

young to rule in his father's place. For unknown reasons he and his widowed mother were abandoned by the rest of the Borjigin clan, who switched

their allegiance to the Tayichi'ut tribe.

This caused great bitterness among Temujin's family, who suffered years of hardship scraping a living through fishing and hunting for marmots and

field mice. At one point Temujin and his younger brother Qasar even murdered their half brother Bekter for stealing a fish and a lark from them.

When the Tayichi'ut leader discovered that Temujin and his family were still surviving alone in the wilderness he organized a search for him -

Temujin was still the rightful heir to his late father's position of ba'atur and therefore remained a future threat. Temujin was captured

and became a slave of the Tayichi'ut, forced to wear a cangue or yoke until he finally managed to escape while his captors were celebrating a spring

festival.

When Temujin was about 15 years old he returned to the Onggirat tribe to claim his fiancée Börte. Her parents welcomed him back and allowed

the previously arranged marriage to be consummated. Temujin then returned to his mother and brothers with his new bride and her mother along with

Börte's dowry, a coat of black sable intended as a present for her new mother-in-law.

As a young married man Temujin needed better security for his family and decided to seek the support of a patron. He first assembled a small band of

loyal supporters around him including some of his brothers. The shrewd Temujin then journeyed to the Tu'ula River for an audience with Toghrïl,

the Ong Khan of the Kereyits, who had sworn anda or brotherhood with his late father. Temujin offered his services to Toghrïl along with

a gift of the sable coat, effectively obliging Toghrïl to become his overlord, in effect an adopted father. In return for Temujin's services

Toghrïl promised to assist him with the reunification of his people. In time Temujin became a loyal member of Toghrïl's retinue.

Several years later, possibly around 1184, members of the Merkit tribe kidnapped Temujin's new wife Börte, probably in revenge for the fact that

Temujin’s father had kidnapped his own wife from the Merkit. The steppe tradition of honour demanded that he should avenge this act. Temujin sought

military assistance from his patron Toghrïl, the Kereyit Ong Khan, and Jamuqa, his childhood blood-brother who was the chief of the Jadaran tribe.

Both regarded the Merkit as an enemy. Temujin led a force claimed to be 40,000-strong against the Merkit, destroying their gers, killing the

men, and enslaving the women and children.

Shortly after this victory Temujin and Jamuqa separated, possibly because of their conflicting ambitions. Jamuqa was a legitimate tribal leader, part

of the established tribal aristocracy and keen to increase his authority. Temujin was an underdog and an outsider, albeit highly motivated to reunite

his clan after forfeiting his position as its rightful leader. Nevertheless Temujin's link with Toghrïl and his successful conquest of the Merkit

greatly enhanced his reputation among the surrounding nomads. One of Temujin's attractions was his reputation for generously rewarding his supporters.

In time he began to gather a larger following, being joined by splinter groups from various clans, especially the Kiyat, Jalayir, and Ba'arin. Many

families switched their loyalty from Jamuqa, including some from his own Jadaran tribe and several important aristocrats from the Borjigin clan. In

about 1185 the senior members of Temujin's growing federation formally elected him as their Khan, giving him the title Chinggis (the meaning of which

still remains unknown, although much debated).

|

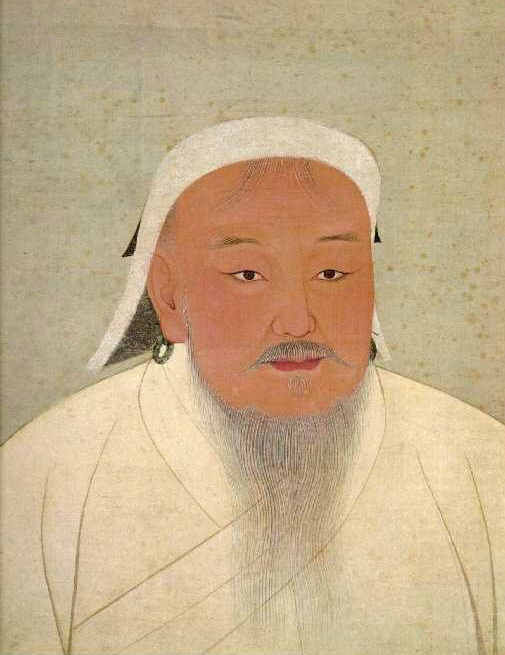

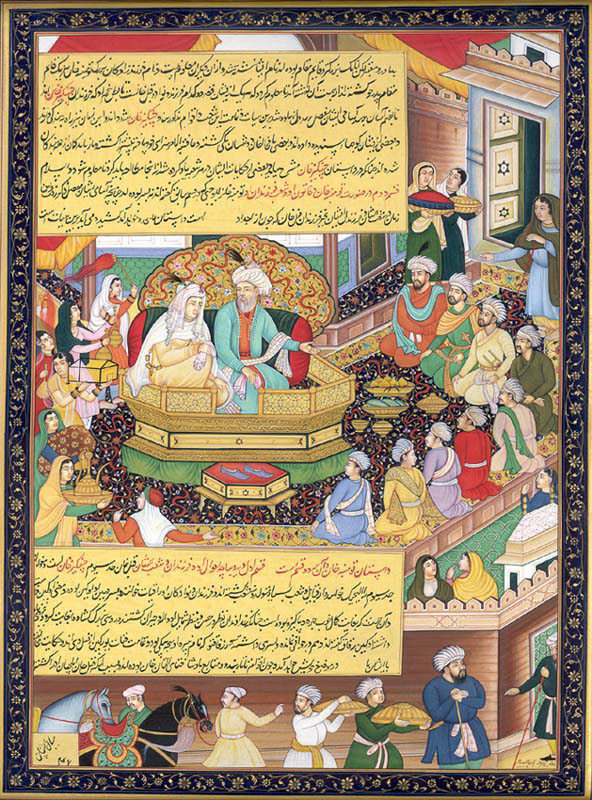

We know only a little about Chinggis Khan's appearance. The above portrait was painted some 30 years after his death and unrealistically depicts him

as a wise old sage of Chinese appearance rather than as a battle-scarred Mongol warlord. Meng Hung described Chinggis Khan as a very large man with a

wide forehead, a long beard and enormous self-control. Juzjani obtained a description from those who had seen him during the invasion of Khurasan

(when he was about 65). He described him as tall, with a strong constitution, "cat's eyes", and a small amount of grey hair on his head

Mongol Unification

Jamuqa was unhappy that some of his former supporters had voted for Temujin's election and clearly saw that his old friend was becoming a serious threat.

It took a small incident, which occurred around 1187, to ignite a conflict between the two neighbouring Mongol tribes. One of Jamuqa's tribesmen stole

a horse from a member of the Jalayir, vassals of the Borjigins. The thief was pursued and killed. In response Jamuqa gathered a coalition of warriors

from the Jadaran and 13 other tribes and rode against Chinggis Khan. Pre-warned of the attack, Chinggis met his approaching enemy on the marshes of

Dalan Baljut. However Chinggis was soundly routed and sought refuge in the Jerene Gorge. Many years later Chinggis berated Jamuqa that after fleeing

into the gorge he had suffered great distress. At a banquet following the defeat, a silly dispute escalated into a major fight between Chinggis Khan's

supporters and their Mongol allies, the Jürkins.

At this point "The Secret History" contains a gap of about ten years, suggesting that something happened to Chinggis Khan during this period that was

too embarrassing for its author to mention. Some writers have proposed that Chinggis may have been forced to seek exile with the Chin. Support for

this idea comes firstly from the writings of Meng Hung, the Sung dynasty general, who reported that Chinggis Khan spent ten years as a slave of the

Chin, and secondly from the flight of Toghrïl Khan to the Qara Qithay. The defeat at Dalan Baljut seriously weakened Toghrïl's leadership

position within the Kereyit. As already mentioned, Toghrïl Khan had originally achieved power by committing fratricide and one of his half

brothers Erke-qala had fled to the Naimans. Now with the backing of the Naiman leader, Inanch Khan, Erke-qara removed Toghrïl from power and

banished him from Mongolia.

It is interesting that on his re-emergence, in about 1196, Chinggis Khan is found leading a successful attack on the Tatars, an attack instigated by the

Chin. One year earlier when the Chin were attacking the Onggirat, one of their allies - a Tatar chieftain - rebelled. In response the Chin turned on

the Tatars, driving them north. Now Chinggis Khan joined forces with the Chin and called on the Jürkin tribe, who were closely related to the

Borjigins, to join forces with him. The Jürkins failed to respond and so Chinggis attacked the Tatars alone, killing one of their leaders and

capturing much booty. Chinggis Khan now turned on the Jürkin tribe, hunting down the tribal leaders and beheading them.

It was at about this time that Chinggis seems to have been reunited with his old patron, Toghrïl Khan, and agreed to assist him to regain his

leadership over the Kereyits. Following the death of Erke-qala, the latter was now divided under the rule of Inanch Khan's two sons. Chinggis and

Toghrïl first set out for the Altai and successfully attacked one of the Kereyit leaders, but on their return they were intercepted by a Naiman

army. The two allies prepared to do battle with the Naiman the following morning, but by daybreak Toghrïl Khan had fled, leaving Chinggis Khan

with no option than to do the same. Instead of attacking Chinggis Khan, the Naiman army pursued Toghrïl Khan and captured many of his supporters,

including some of his family. Despite his treacherous desertion of the battlefield Toghrïl had no hesitation appealing to Chinggis for assistance,

who faithfully responded by sending troops led by four of his most capable commanders – Bo'orchu, Muqali, Boroqul and Chila'un. With the Naiman

overthrown and his tribe reunited, the elderly Toghrïl began to contemplate the future leadership of his people and realised that Chinggis Khan

would make a much finer choice than either his own son or his brothers.

Many scholars have speculated on the reasons for this extraordinary display of loyalty by Chinggis and disloyalty by Toghrïl. One explanation

is that Chinggis demanded the Kereyit throne as a condition for supporting Toghrïl in battle, which Toghrïl refused. Having been ravaged

by the Naiman, Toghrïl could only obtain Chinggis’s assistance by agreeing to his terms. According to Rashid ad-Din the two leaders now united

to wage a joint campaign against the Tayichi'ut.

The conquest of the Jürkin, Naiman, and the Tayichi'ut sent out a warning to the other tribal leaders that Chinggis Khan was bent on tribal

domination. The Qatagin, Salji'ut, Dörben, Tatar, and Onggirat tribes formed a coalition against Chinggis Khan and fought a bitter battle near

the Onon river. According to Rashid ad-Din the coalition was defeated, although it seems more likely that they were successful since Toghrïl

retreated to the Manchurian border and Chinggis to northern China. Sensing victory the tribal leaders assembled a new coalition in 1201, composed

of members of the Jadaran, Dörben, Ikire, Onggirat, Qatagin, Qorola, Tayichi'ut, and Salji'ut tribes, as well as factions from the Merkit, Oyirat,

Naiman, and Tatar. It was to be led by Chinggis Khan's childhood friend Jamuqa who they had elected as their "Universal Leader" or Gurkhan.

Toghrïl received advanced warning of developments and joined forces with Chinggis. The two opposing armies encountered each other near to the

Khalka River and on this occasion the coalition was routed, although Chinggis was badly injured in the neck by an arrow. After the battle Chinggis

turned on the Tayichi'ut and slaughtered every male in the leadership lineage.

|

Chinggis now felt strong enough to turn his focus back onto the Tatars, the tribe that had caused so much misery among his ancestors and had enslaved

many of the Mongol tribes. It was normal for a nomadic army to be distracted by plunder rather than to strive for total victory, but on this occasion

Chinggis instructed his warriors to concentrate on victory first. The battle took place at another location close to the Khalka River in 1202 and the

Tatars were overwhelmed. Afterwards their tribal leaders were exterminated and the survivors were distributed among the members of the Mongol

confederation.

To strengthen the alliance between the Mongols and the Kereyits, Chinggis Khan proposed two arranged marriages – the first between his eldest son

Jöchi and one of Toghrïl's daughters and the second between Toghrïl's son Senggum and one of Chinggis's daughters. Senggum immediately

rejected the plan outright as did his father. These events make more sense if one accepts the premise that Chinggis had already negotiated his

succession to the Kereyit throne in place of Senggum.

Indeed it was at the instigation of his son Senggum that Toghrïl Khan finally responded to Chinggis's rising power. In 1203 Toghrïl

allowed Senggum to lead his Kereyit warriors in an alliance with Jamuqa's remaining forces against Chinggis Khan. It seems that the Mongols were

unprepared for the joint attack and fled eastwards towards the Manchurian border. They desperately needed reinforcements and managed to get the

Mangqut and the Uru'ut to defect from Jamuqa to the Mongol side. Despite these gains, at the crucial battle of Kalakalzhit-elet the Mongols were

still badly outnumbered. Although both Senggum and Chinggis's son Ögedey were badly wounded by arrows during the fighting, the Mongols

had suffered the heaviest losses by far and were forced to retreat.

Both "The Secret History" and Rashid ad-Din report that Chinggis Khan was in a critical situation, his army reduced in size to just a few thousand.

He sought refuge in the south-east of Mongolia in the swamplands of Baljuna. From there he sent out requests for reinforcements and managed to enlist

the help of the Onggirat, the tribe that had traditionally provided brides for the Borjigin clan, along with many other Mongol tribes, including the

Ikires, the Nünjin and the Saqayit. Even non-Mongol tribes such as the Kitan rallied to his side. Chinggis also despatched messages to the leaders

within the opposing coalition encouraging them to switch sides, and many warriors defected from the Kereyit in response. Chinggis Khan, Senggum, and

Jamuqa all knew that their next encounter would be crucial – the winner would become the ultimate ruler of Mongolia. To cement the loyalty of his

new federation Chinggis Khan swore an oath that he would share the spoils of war equally among his supporters. To reinforce their commitment he and

his tribal leaders all drank a draught of the muddy waters of the Baljuna. Those involved would go down in history as the Baljuntu, or the

muddy-water drinkers.

Chinggis still lacked sufficient strength to engage in battle but when his brother Qasar and his followers were seriously attacked by the Kereyit

while trying to join Chinggis in the Baljuna, he decided to act. Qasar's family were being held hostage by the Kereyit, so Chinggis organized a

message to Toghrïl Khan from Qasar saying that Chinggis had fled and that Qasar now hoped that he could join Toghrïl's coalition. While

the Kereyit celebrated their apparent victory over the Mongols, Chinggis led his forces through the night to Toghrïl Khan's encampment. Despite

the element of surprise, a three-day battle ensued during which Toghrïl was accidentally killed and Senggum fled to Kashgar via Tibet where he

was later captured and massacred. The vanquished Kereyit forces were integrated into Chinggis's growing federation and their commanders and tribal

leaders were for once treated with mercy.

Chinggis now appealed to the other members of the opposing coalition to join him in victory and the Oyirats and Onggirat responded positively. However

the majority rallied around the Naiman instead, the only significant remaining tribe standing in the way of total Mongol domination. The Naiman had

nothing but contempt for the Mongols and appealed to the Ongut for support. However the Ongut leader had good relations with Chinggis Khan and informed

him of the Naiman plans for war. The Mongols responded with a complete military reorganization, dividing their forces into regiments of one thousand

and creating an elite bodyguard. In 1204 the Mongols rode against the Naimans, who were probably superior in numbers and overconfident of victory. At

a major battle close to the future site of Qaraqorum, the Naiman were finally overwhelmed despite fighting to the bitter end. They were not helped by

the flight of Jamuqa before the commencement of hostilities or by the flight of the Merkits during the battle. Chinggis's General, Sübetey,

was left to round up the remaining Merkit forces. Meanwhile Jamuqa was handed over to Chinggis Khan by his own people for execution.

|

Chinggis Khan had united virtually all of the "people of the felt-walled tents". In the spring of 1206 he summoned all the tribal leaders to a

gathering or quraltai at the source of the Onon. There he proclaimed himself khagan (khan of khans) of all the Turkic-Mongol

tribes throughout eastern Central Asia. The quraltai was also important for another reason. Chinggis's appointment was endorsed in the

name of Tengri by the most senior Mongol shaman of all, a Qongqotan named Kököchü. However once Chinggis became aware that

Kököchü was scheming behind his back he organised his swift elimination. Chinggis Khan was now firmly in control of both the material

and the spiritual world.

Chinggis Khan seems to have applied the term Mongol to himself to emphasize that he was the rightful ruler of the Three River Mongols. However

according to Meng Hung the word "Mongol" that we universally use today may have been relatively unknown to the people under his rule. They were

more likely known to each other as Tatas or Tatars.

Over the following years yet more tribes joined the Mongol confederation. In 1207 an expedition under Jöchi, Chinggis's eldest son, secured

the submission of many of the forest tribes living along the Yenisey River in southern Siberia, including the Oyirat and the Kyrgyz. In 1209 the

Uighurs of Turfan renounced their support for the Qara Qithay and were peacefully incorporated into the confederation. In 1211 the Qarluq of the

lower Ili likewise renounced Qara Qithay rule in favour of the Mongols.

Jöchi returned to the Yenisey in 1217 and, with help from the Oiyrat, put down a regional revolt led by the Tumat. Following a purge of the

rebels all of the remaining forest tribes were absorbed into the Mongol confederation.

The Qara Qithay

After the Jürchids overthrew the Kitans (also known as the Liao) in 1125, a small splinter group fled westwards into Turkestan. They were a

warlike Buddhist people of Mongol origin and soon attracted a following of local nomadic tribes. After consolidating their position they formed an

alliance with the Eastern Qara-khanids, who were struggling to control their unruly Turkish subjects, a mix of Uighurs, Qangli and Qarluq. After

occupying the Qara-khanid capital of Balasagun on the upper Chu, west of Lake Issyk Kul, the Qara Qithay exploited divisions among their Qara-khanid

hosts and seized power in 1134. They then attacked the Western Qara-khanids, first defeating them at a battle in the Ferghana Valley in 1137 and then

overwhelming a combined Qara-khanid and Seljuk army at the Battle of Qatwan north of Samarkand in 1141. The Qara Qithay continued their surge westwards,

conquering the Seljuk vassal state of Khorezm in the same year. In a matter of years they had gained control of the whole of East Turkestan (today

Xingjiang), Transoxiana, and Khorezm.

The Chinese called this new Qara Qithay state the Western Liao dynasty although Western historians refer to the Qara Qithay Khanate or Empire. The

Qara Qithay leader adopted the modest title of Gurkhan, "Universal Leader". However he did not assume direct governance but chose to rule

through Qara-khanid amirs, while Khorezm was forced to pay annual tribute as a vassal state. Khorezm attempted to free itself from Qara Qithay

domination on two occasions during the 1170s but failed. However the Qara Qithay regime steadily declined under the rule of the Gurkhan

Ye-lü Chih-lu-ku (1178-1211) who preferred worldly pleasures to government. In 1209 the Uighur ruler renounced Qara Qithay rule in favour of

the Mongol confederation as did the leader of the Qarluq of the lower Ili in 1211.

After the defeat of the Naiman in 1204, the Naiman Khan's son Küchlüg fled westwards with his supporters. In 1208 Chinggis Khan led another

raid on the Naiman who were then living on the upper Irtysh. They were driven further west towards the Tarim Basin oasis of Kucha and into the Empire

of the Qara Qithay. Whether by force or through ambition, Küchlüg, a Nestorian Christian, entered the service of the elderly Qara Qithay

Gurkhan, who was facing an increasing military threat from Muhammad, the Shah of Khorezm. After marrying the Gurkhan's daughter,

Küchlüg regrouped and reinforced his Naiman warriors, turning them into a powerful military force supposedly in the service of the

Gurkhan.

However Küchlüg was scheming and ambitious, making a secret pact with the Khorezmshah to overthrow the ruling Qara Qithay dynasty and to

divide and share their lands. The Khorezmians duly opened hostilities against the Qara Qithay in 1211 but events did not proceed to plan. The Qara

Qithay army made a strong counter-attack and occupied Samarkand. The tide was turned by the general Turkish population who took the opportunity to

close the gates of their Balasagun capital against the returning Qara Qithay army. During the confusion Küchlüg seized his chance and

usurped the throne, although it was only after the death of the old Gurkhan in 1213 that Küchlüg adopted the title of

Gurkhan himself.

Küchlüg was disturbed to find that many of the Moslem Turk chieftains now under his control were actually supporters of the hated Chinggis

Khan. A Nestorian himself, he began a campaign of persecution against them, based on their Muslim religious faith.

Mongol Expansion in the East

Despite his growing power Chinggis Khan was acutely aware of the ever-present military threat posed by China. The Chinese people were at that time

ruled by three separate states – the Chin in the north, the Sung in the south, and the Tangut state of Xi-Xia in the west. The latter was located

just south of the Gobi desert, controlling the trade routes from China to the west. Both the Chin and the Xi Xia had previously irritated the

Mongols by interfering in their intertribal wars.

Of course the Mongol victories to date had all been won in battles against other nomadic peoples in the open steppes. Any invasion of China would

need to overcome large standing armies and heavily defended citadels. Ever cautious, Chinggis began his campaign by attacking the weakest state of

Xi Xia. In 1207 he crossed the Gobi desert and began probing the Tangut defences but soon encountered difficulties. The Mongols had no military

engineers, no siege engines, and no artillery, so were unable to overwhelm the citadel of Volohai other than by means of prolonged siege. Eventually

the Tanguts sued for peace and promised to pay tribute. However the tribute never arrived and in 1209 Chinggis invaded again, in force. This time

he faced an even bigger obstacle, since the capital city of Ningshia was even more heavily fortified. An attempt to dam the Yellow river ended in

disaster for the Mongols when the dam broke. Victory was only achieved after another lengthy siege. The Mongols departed with booty, young brides,

and a promise of future military support. Even so the complete subjection of the Xi-Xia would not be accomplished until 1227.

The results to date did not bode well for an attack on the Chin dynasty of the Jürchids. Their northern frontier was guarded first by the Onguts,

who were allies of the Chin, and secondly by the Great Wall. Whatever Chinggis's plans at the time, they were overtaken by events. In 1210 the

Jürchid "Golden King" died and Chinggis Khan was invited to kowtow to his antecedent as a vassal at the capital of Zhongdu, close to modern Beijing.

Chinggis was incensed and spurred into action. He was fortunate in having only recently secured the alliance of the Onguts during the Mongol

inter-tribal wars and he now ensured their loyalty for his forthcoming war against the Chin. The Mongol campaign began in 1211 and was to continue

for 23 years before achieving the complete destruction of the Chin Empire. Once again the Mongols proved to be a formidable force in open steppe warfare

but encountered major problems in trying to penetrate the heavily fortified Great Wall. It was not until 1213 that Chinggis's young General, Jebei Noyan,

managed to break through the Wall at the Nan-kou Pass, opening the way to old Beijing. The Mongols stormed south avoiding the fortified cities and

pillaging all the way. On their return the enthusiastic Mongol troops decided to assault the heavily defended citadel of Zhongdu, much against Chinggis

Khan's wishes. The attempt was a disaster with heavy Mongol losses.

After returning to Mongolia with enormous booty Chinggis was surprised to receive news that the Golden King had fled Zhongdu for the city of Kaifeng,

south of the mighty Yellow River. Sensing an opportunity Chinggis ordered his main commander in the east, Muqali, to return with Jebei and to take the

capital. This time the Mongols rounded up large numbers of disaffected Chinese, Kitan, and Jürchids to assist in the siege. The city finally

submitted in May 1215. The defenders were massacred in their thousands, the palace was incinerated and the city looted for a month.

The trusted Muqali was left in charge of the campaign against the northern Chin and by 1223 had confined Chin resistance to just one province. This

conflict gave the Mongols experience of a new type of warfare involving the siege and assault of strongly fortified positions. In the process they

became experts in the art of siege warfare, recruiting large numbers of skilled Kitan and Jürchid auxiliaries and Chinese engineers into their ranks.

Relations with Khorezm

Khorezm at this time was a prosperous and cultured state, consisting of a settled Islamic population of mixed Turkic-Iranian stock on the one hand and

a nomadic pagan population of Turkic tribes on the other. The former were known as Sarts, although the Mongols called them the Sartul. We know from

Yaqut that at the start of the 13th century these Khorezmians were Turks in both appearance and moral values. The nomads were frequently hostile to

each other and were known generically as Qipchaqs. The Qanglis were essentially the eastern branch of the Qipchaqs and roamed well north of the Aral

Sea.

Khorezm was ruled by the unpopular Khorezmshah Ala ad-Din Muhammad, whose military power was dependant on unreliable mercenaries drawn from the

surrounding nomadic tribes. With the erosion of Seljuk, Ghaznavid, and Qara Qithay power, the Anushteginid dynasty of Khorezmshahs had built Khorezm

into the strongest empire in the eastern Islamic world. They controlled the Khorezm oasis, the Ustyurt, Mangishlaq, the lower and lower middle Syr

Darya, the Qizil Qum, the Qara Qum, northern Afghanistan, and northern and central Iran. Following his alliance with the Naiman Prince Küchlüg,

Muhammad had overcome Qara Qithay domination to incorporate the whole of Transoxiana into his Empire. He now chose to rule from Samarkand (in fact the

citadel of Afrasiab). According to Ibn al-Athir, the khutba or Friday sermon was recited in Muhammad's name even in distant Oman!

Muhammad was not a modest man and referred to himself as the "Second Alexander of Macedon". His royal seal bore the expression: "The Shadow of God on

Earth". The expansion of his Empire had involved a heavy price. The urgent need for money to finance the military expansion had led to hardship and

disaffection, particularly outside of Khorezm itself. Taxes were sometimes collected not once but twice a year and the peasants were conscripted for

military service. Wherever the Khorezmian armies penetrated they established a reputation for violence, cruelty, and extortion making them highly

unpopular and a focus for intense hatred. Not once did they create a bond of mutual self-interest between themselves and their subjects in any one of

the provinces that they conquered. They alienated local elites by removing established ruling dynasties and installing their own family cronies. Last

but not least the Empire was fundamentally divided, Muhammad ruling from his new capital of Samarkand and his powerful Qangli mother, Turkan-Khatun,

from Gurganj.

Whether Chinggis Khan secretly harboured a long-term plan to conquer his new and egotistical neighbour is unclear. Given the expansionist plans of

both Empires it is likely that a conflict at some time was inevitable. With his relentless pursuit to unify the steppe nomads in the east Chinggis Khan

must have considered the possibility of extending his confederation to encompass the Qipchaq nomads to his west. On the other hand he must have been

concerned about the potential threat posed by the Khorezmshah's substantial military resources. In any event, at that precise moment many of his own

forces were engaged in the war against the Chin in the east.

Whatever his thoughts, the initial contacts between the two leaders were generally diplomatic and cordial.

Juzjani tells us that in 1215, just after the conquest of Zhongdu (old Beijing), Muhammad dispatched an embassy to China. Juzjani seems to have

obtained his information directly from Baha al-Din Razi, the Khorezmian ambassador. Muhammad had aspirations of his own towards the conquest of China

and on receiving news of the Mongol campaign became keen to gather intelligence on their progress. On their approach to the city the ambassadors

passed a huge pyramid built from the bones of the slaughtered and found the ground underfoot was greasy with the fat from rotting corpses. Certain

members of his party fell sick through infections and some died. Chinggis Khan received the envoys graciously, theatrically introducing an element of

threat by presenting the Chin Emperor's son and vazir (prime minister) bound in chains. Chinggis ordered the ambassadors to inform their

master that while he considered himself to be the ruler of the East he perceived the Khorezmshah to be the ruler of the West. There should be peace

and friendship between the two rulers and merchants should be free to travel from one country to another.

|

Chinggis Khan responded by sending two envoys and a trading caravan to Muhammad, bearing lavish gifts, including a nugget of Chinese gold the size of

a camel's neck. One of the envoys was probably a Khorezmian in the service of the Mongol court called Mahmud Yaslavich, who would one day be the

governor of northern China. This may well have been the same embassy mentioned by Nasawi, which reached Muhammad in Transoxiana, probably Bukhara, in

early 1218. It arrived with a message from Chinggis Khan saying that he had heard of Muhammad's victories (in Transoxiana) and requesting a treaty of

peace and friendship, as well as the free movement of merchants between their territories. Chinggis Khan noted that he placed Muhammad "on a level with

the dearest of his sons", in other words the level of a vassal, a huge insult to the vain Khorezmshah.

According to Juvaini, the Mongol desire for peaceful trade was quickly exploited by three Central Asian merchants, who organized a caravan of lavish

goods and textiles to trade at the Mongolian court. Chinggis arranged for 450 Muslim merchants to join the return caravan (composed of 500 camels

according to Juzjani) with funds of gold and silver to acquire yet more luxuries from Central Asia. The heavily defended caravan arrived at the

Khorezmian border oasis of Otrar, on the middle Syr Darya, in 1218, led by the Mongol emissary Uquna. According to Juvaini the merchants had brought

the following message from Chinggis Khan to Shah Muhammad:

"The areas which bound on our territory have been purged of enemies and have been completely conquered and subjugated to our will; and we now have the obligations of neighbours. Human wisdom so requires it; that the path of concord should be trodden on either side; that the duties of friendship should be observed; that we should bind ourselves to aid and assist one another in the event of untoward happenings; and that we should keep open the paths of security, frequented and deserted, so that merchants may ply to and fro and without restraint."Surprisingly the governor of the main citadel, Ghayir Khan from the Qangli tribe and an indirect relative of Muhammad, had the merchants arrested. The governor sent a message to the Khorezmshah, on campaign in central Iran, who authorized the massacre of the merchants (many of whom probably originated from Khorezm) and the seizure of their property. The reasons for this action still remain unclear – Juvaini makes the unlikely suggestion that it was because an Indian merchant, who had known the governor in former times, insulted him by calling him Inalchuq (little Inal). More likely reasons are that either the Khorezmians did not want to see Mongol intervention in their commercial trade relations or that they feared that the caravan concealed Mongol agents - which it very likely did. Whatever triggered the massacre, the Khorezmshah confidently saw himself as the ruler of a dominant power, capable of withstanding any possible military retaliation.

|

Chinggis Khan had succeeded in assembling a large federation of Mongol and Turkic tribes, covering a variety of faiths – shamanistic, Buddhist, and

Nestorian. He had restructured his civil and military administration, introduced a culture of iron discipline, created an elite military bodyguard,

and laid down a system of law with a detailed criminal code. His troops were battle-hardened and thanks to his campaign against the Chin his army

had become skilled in siege craft and had recruited specialized military engineers and sappers.

The detailed planning of the forthcoming assault on Khorezm was primarily the responsibility of Sübetey-ba'atur, one of the Mongols ablest and most

cunning generals who was now effectively Chinggis's chief-of-staff. Sübetey decided that the invading force would be divided into four cavalry

detachments, each with its own corps of artillery and engineers. They were to be led respectively by Chinggis and Toluy, Jöchi and Sübetey,

Ögedey and Chaghatay, and finally Jebei.

The first priority was to eliminate the threat from the remaining Naiman and Merkit forces in the west. Küchlüg had not only strengthened

his Naiman forces after gaining control of the Qara Qithay territories but had formed a military alliance with Khorezm. After Chinggis had returned

from China he had received many messages from tribal leaders in East Turkestan who were dissatisfied with Küchlüg's leadership, requesting

his urgent intervention. One request had come from the townspeople of Almaliq, whose Amir, Ozar, had been killed by Küchlüg. The defeat

of his old Naiman enemy would open up the opportunity for Chinggis to form alliances with some of these Turkic nomadic tribes. Meanwhile the Merkits,

who had been displaced from the Upper Yenisey, had fled to the Qipchaq steppes to the north of the Aral Sea, close to the northern border of Khorezm.

Before the onset of the winter of 1218 Jebei was despatched with an army of two toumens (20,000 warriors) into Eastern Turkestan to eliminate

Küchlüg. Jöchi and Sübetey followed with a second army from China with the initial objective of destroying the Merkits. Skirting

the south of the Altai the two armies moved together towards the Tien Shan. Jebei headed north to Almaliq in the Ili valley, just east of modern Almaty,

while Sübetey headed west through the Tarim basin and into the Ferghana Valley. By now Küchlüg had fled across the Tien Shan to Kashgar.

As Jebei followed he was received as a liberator sent to restore religious freedom and quickly gained widespread local support. Küchlüg

was forced to retreat into the Pamirs where he was hunted down and beheaded. The whole of Eastern Turkestan had suddenly fallen under Mongol rule.

Before long news arrived in Khorezm that intruders had appeared in the "home of the Qangli" in the Aral Qara Qum region, located beyond the Syr Darya

to the north-east of the Aral Sea. By now Muhammad had returned to Samarkand from central Iran, leaving one of his sons, Rukn ad-Din, in charge of

events. Muhammad led an advanced party to Jand, where he discovered that the transgressors were Merkits, attempting to flee the Mongol force led by

Jöchi. According to Juzjani, Muhammad went back to Samarkand for reinforcements before returning to Jand and continuing north into the Turgay

region. By either a remarkable coincidence or a literary convenience, he arrived in mid July 1219 on the day after the Merkits had been annihilated.

Muhammad pursued the Mongols, who refused to engage in battle with him, saying they had no authority to do so. Nevertheless a skirmish ensued after

Sultan Muhammad stubbornly proclaimed that all infidels were his enemies. After casualties on both sides the Mongol army retired under cover of

darkness, lighting camp fires to conceal their intentions. When Muhammad entered their camp at daybreak, he found that the Mongols had discreetly

departed a long time ago. Juzjani, a strong supporter of Muhammad's dynasty, believed that this encounter left a scar on the Khorezmshah, which

adversely affected his conduct in the forthcoming conflict.

During that same summer of 1219 Chinggis Khan and his two sons Chaghatay and Ögedey assembled their respective Mongol armies on the Upper

Irtysh River in the southern Altai. Requests had been sent out to all the tribal leaders of the confederation for the donation of military forces –

only the Xi-Xia declined to oblige, an act for which they would later be severely punished. Travelling west they reached Qayaliq that autumn, close

to today's Taldy Kurgan, to the south-east of Lake Balkash. There they were joined by Uighur and local Qarluq detachments as well as by Qarluq forces

from Almaliq. Their army of Mongols, Turks, Tanguts, and Han Chinese was perhaps between 50,000 and 100,000 strong, remembering that Chinggis Khan's

entire army was only 95,000 strong in 1206 and 129,000 strong at the time of his death. Earlier scholars, ranging from Juzjani to V. V. Barthold,

have exaggerated the numbers.

|

It is difficult to estimate the comparable strength of the opposing Khorezmian forces composed of Qipchaq and Sart auxiliaries, the majority of whom

had little commitment to the reigning Shah. Most scholars believe that they were considerably larger in number. News of the main Mongol advance

probably reached Muhammad during the depths of winter in Samarkand. It is possible that the intelligence gathered by the Khorezmian embassy to China

suggested that although Mongol forces were formidable in steppe warfare, they were poor in capturing well-defended fortresses. Work therefore began

immediately on the reinforcement of the city with the construction of a moat and the installation of a large defence force - 110,000 men according to

Juvaini, 60,000 elite Turks and 50,000 Sarts. Muhammad conferred with his advisors, one of whom (possibly his son Jalal ad-Din) proposed that they

should confront the advancing Mongol army head-on. With his troops widely dispersed to maintain control over his dominions, and the mutual hostility

between some of his tribal mercenaries, this was not an easy option. Other advisors suggested that Transoxiana was undefendable and recommended

withdrawing to Khurasan, exploiting the Amu Darya as a defensive barrier. Yet others proposed making a stand in Afghanistan, falling back across the

Indian border if necessary. Muhammad initially chose the latter option, organizing defensive garrisons across Transoxiana before heading for Balkh.

An advanced guard of sappers had prepared the forward route for the main Mongol army. The Mongols were used to cold weather and preferred to manoeuvre

and fight in the winter when they could easily cross the frozen rivers. After passing through Semirechye and crossing the Chu and Talas rivers,

Chinggis headed towards the Syr Darya, making contact with the force led by Jöchi and Sübetey before reaching Otrar. While Jöchi was

left to advance down to the mouth of the Syr Darya, Chaghatay and Ögedey were left with the Uighur division to lay siege to the city.

Chinggis received intelligence in Otrar that the defences had been heavily reinforced around Muhammad's capital of Samarkand and he therefore decided to

make a surprise attack on Bukhara instead. With Sübetey and his youngest son Toluy he crossed the Syr Darya to reach the small fortified town

of Zurnuq, which surrendered peacefully. From here he set out with the bulk of the Mongol forces to cross the Qizil Qum by way of a local caravan route,

using the assistance of local Turkmen guides.

Otrar finally fell in February 1220 after months of siege, the governor Ghayir Khan holding out until the bitter end. Most of the inhabitants were

killed.

|

At about the same time Chinggis reached Bukhara via the town of Nurata, which also surrendered to Sübetey without a fight. The sudden arrival

of the Mongol army outside Bukhara, some 600km behind enemy lines, must have created panic. It was one of the most audacious outflanking manoeuvres

of all time. The citadel was defended by some 12,000 to 30,000 soldiers, but after only three days of siege the garrison fled from the town only to be

cut down by the surrounding Mongols. The townsfolk surrendered the following day, although a hard core of the Sultan's army put up a strong resistance.

The town was bombarded and set on fire, the Mongols eventually assaulting the walls, driving the local populace before them as human shields. The

remaining defenders were all massacred, the outer walls were destroyed and the town was burnt and pillaged. Bukhara had capitulated within just weeks.

Chinggis and Sübetey must have been surprised at the lack of resistance shown by the Khorezmian forces and confidently headed straight for

Samarkand, driving columns of captives ahead of them. There they were joined by reinforcements from Mongolia, Jebei having successfully negotiated

the frozen passes of the Pamirs during winter to reach the Ferghana Valley and Samarkand. Finally Chaghatay and Ögedey arrived after a

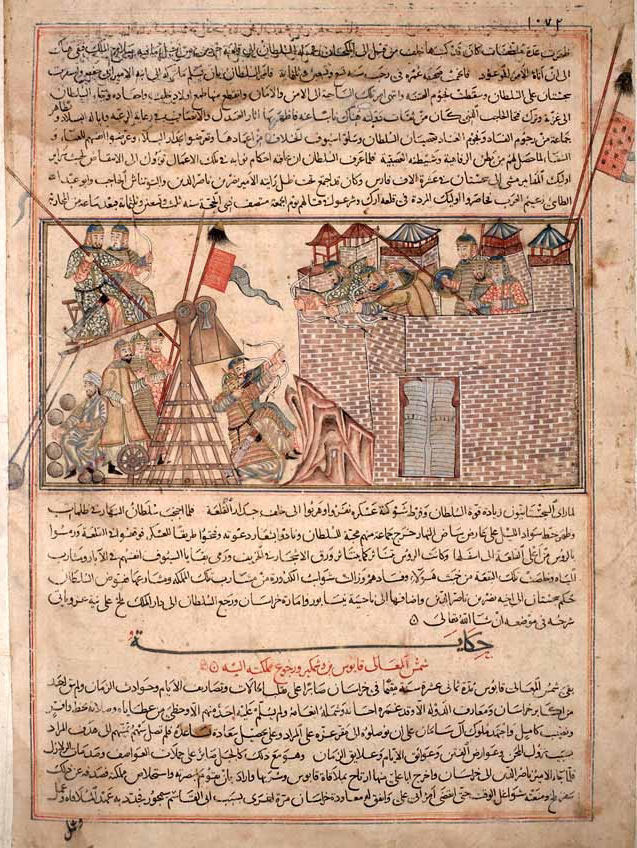

long but successful siege at Otrar with hordes of prisoners captured along the Syr Darya. After inspecting the defences for two days Chinggis ordered

his forces to lay siege to the city. The Turkish defenders made sorties out from the town into the surrounding Mongol ranks, resulting in casualties

on both sides. As a result the Mongols sealed the gates and bombarded the city with their mangonels.

|

As a last desperate move the defenders deployed their twenty war elephants but to no great effect. Despite months of reinforcement the city surrendered

on the fifth day, the 19th March. One small group of diehards escaped to join the Khorezmshah and another retreated into the cathedral mosque to fight

a last ditch battle, the Mongols setting fire to the building using naphtha. Some 30,000 Qipchaq mercenaries were massacred. A further 30,000 of

Samarkand's artisans were rounded up and deported to the various ulus of the Mongolian Empire.

The Kitan Yeh-lü A-hai was appointed darughachi or governor of the city, responsible for a local Mongol garrison, the compilation of a

population register, the collection of tax, the despatch of tribute to Mongolia, the issue of coinage, and the administration of justice. Mahmud

Yalavach, who had been born in Gurganj, was given responsibility for the overall administration of Transoxiana. The Taoist monk K'iu Ch'ang Ch'un

and his entourage spent nine months in the remains of the Afrasiab citadel at various times during 1222 and discovered that, despite the fact that only

one quarter of the population remained, life had quickly returned to some degree of normality.

Arriving in Balkh the Khorezmshah was met by an emissary who persuaded him to change his plans and to head for central Iran. Muhammad promptly set

out for Khurasan, arriving in Nishapur on 18 April 1220. Unaware of developments in Transoxiana, Muhammad took the opportunity to relax and

indulge himself, believing that the Amu Darya would provide a formidable natural barrier to the Mongol army. Unbeknown to Muhammad, Chinggis Khan

had received intelligence following his arrival in Samarkand that the Khorezmshah had already fled south from the city. He gave 30,000 men to his

two field-marshals, Jebei and Sübetey, and ordered them to hunt the Khorezmshah down.

|

On his departure from Balkh, Muhammad had despatched a patrol to a crossing of the Amu Darya close to modern Termez to gather news on developments

north of the river. There they discovered that Bukhara had already fallen and that Samarkand had just been captured. The patrol eventually caught

up with Mohammad at Nishapur to inform him about the fall of Transoxiana and to warn him that Jebei and Sübetey were in hot pursuit, having

already crossed the river. With his confidence collapsing Muhammad set out for central Iran on 12 May, travelling via Isfarayin and Ray before

meeting up with his son Rukn ad-Din and 30,000 Iranian troops at Farrazin. The Iranian emirs recommended that he take refuge in the Kuh-i Ushturan

Mountains bordering Luristan, but Muhammad thought that the terrain was undefendable. He likewise turned down an option to retreat to a citadel on

the border of Luristan and Fars.

The Khorezmshah was finally spurred into action by news that the Mongols had already attacked Ray and were heading towards Farrazin. For the next

six months the Mongols pursued Muhammad and his eldest son, Jalal ad-Din, west and then east across the mountains of northern Iran. Muhammad escaped

through the Elburz Mountains to the Caspian coast close to Mazandaran, finding refuge on a small island in the Bay of Astarabad. It was there that

he died from pleurisy in either December 1220 or January 1221. Jalal ad-Din and two brothers returned to Gurganj by way of Mangishlaq, but Muhammad's

harem, young children, and mother were captured at their mountain stronghold near Hamadan. All his male offspring were killed and his mother was

despatched to Chinggis Khan who sent her to be detained in Mongolia.

After the fall of Samarkand, Chinggis had retreated into the mountains south of the city to rest his troops and horses until the autumn. So far his

campaign had not even touched the wealthy province of Khorezm that had been under the control of the Khorezmshah's Qipchaq mother, Turkan-Khatun.

Chinggis was fully aware that he was a long way from home and that there were still many Khorezmian forces in Afghanistan and Khurasan who could

regroup against him. That autumn Chinggis moved south to the Amu Darya to destroy Termez, moving up river into Tajikistan for the winter.

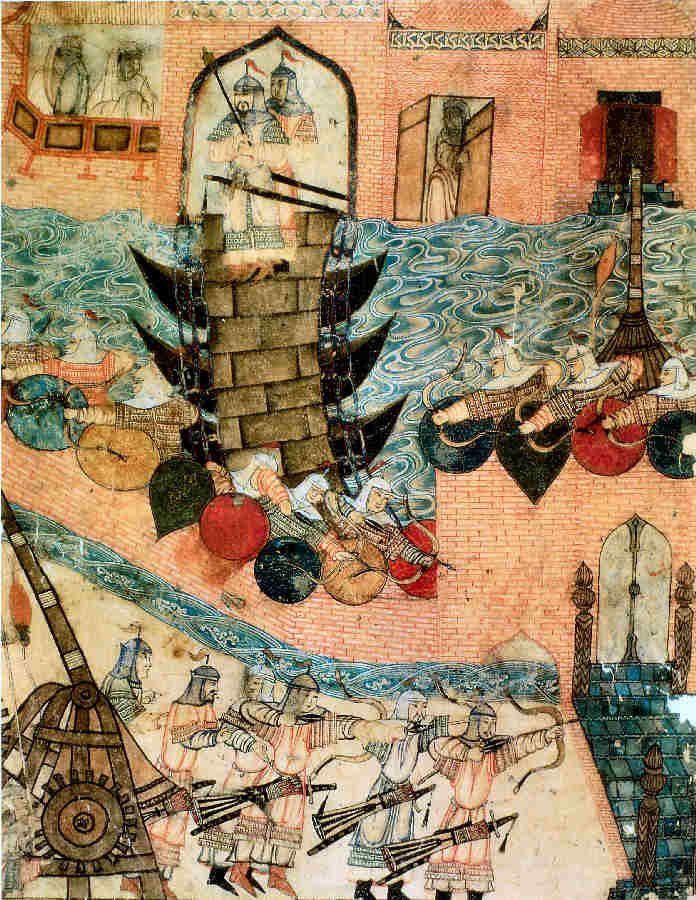

At the start of 1221 his attention turned to Gurganj, the capital of Khorezm, now under the command of the Qipchaq general Khumar Tegin. The siege

of a large town like Gurganj would require more than the forces available under Jöchi, who had arrived from the Syr Darya after capturing Sighnaq, Yangi-Kent

and Jand. Chaghatay and Ögedey had initially been sent from Bukhara to capture Khojand in Ferghana. Now they returned to join Jöchi

with "…an army as endless as the happenings of time", according to the verbose Juvaini.

Rashid ad-Din writes that Chaghatay and Jöchi disagreed over the conduct of the siege of Gurganj. Chinggis, who at the time was supervising the

difficult siege at the fort of Talaqan on the borders of Afghanistan and Khurasan, resolved these differences by placing the younger Ögedey

in command of operations. From Nasawi's account it seems clear that Jöchi made several attempts to negotiate with the defenders, attempting to

minimise the destruction of a prosperous capital city that was destined to become part of his appanage. Of course Jöchi had no general abhorrence

of death and destruction – he had no compunction in destroying the much smaller town of Sighnaq. Juzjani went even further and claimed that Jöchi

not only disagreed with his brothers but also fundamentally disagreed with his father. However Juzjani's account is flawed as we shall see later.

The siege commenced in early 1221 by which time Jalal ad-Din, his mother, and the young princes had fled. It lasted into April. Prisoners-of-war were

used to fill in the surrounding defensive ditch and the city walls were undermined. Because of a lack of stones the Mongols made projectiles for

their catapults out of mulberry tree logs soaked in water.

|

Once the walls were breached the Mongols set fire to the houses using vessels filled with naphtha. A bloody battle ensued as the Mongols took the

city quarter by quarter. The male defenders were slaughtered and the women and children were taken into slavery. One report claimed that 24 male

defenders were killed for each Mongol soldier (of whom, according to Rashid al-Din there were over 50,000).

Either by design, or through later neglect, the dam outside the city was destroyed, allowing the unconstrained waters of the Amu Darya to flood the

remains of the city. According to Juzjani only two edifices remained, "the old palace" and the tomb of Muhammad's father, Sultan Tekesh, who ruled

from 1172 to 1200.

|

Following the fall of Gurganj, Ögedey and Chaghatay led their forces south to join their father at Talaqan in Afghanistan and "were received

in audience". We presume that Jöchi stayed in Khorezm to complete the conquest and to eliminate all resistance. Many of the local Sarts,

especially the artisans, were enslaved and despatched to Mongolia. Juvaini recorded that there were now many localities in the east that were

well-peopled and cultivated by the inhabitants of Khorezm. Before departing Jöchi appointed Chin Timur as the basqaq (administrator and

tax-collector) of the entire province.

The destruction of Khorezm was not exaggerated by the historical writers. The archaeological record proves that the devastation was truly massive.

All the main towns were destroyed: Mizdakhkan, Shemakha qala, Janpıq, Kyat, Gu'ldu'rsin, Kavat qala, Dargan, and Hazarasp, the latter apparently being

"submerged". The left bank irrigation system in the north fell into disuse and the surrounding agricultural regions dried up and turned into desert,

remaining a wilderness until the present day. The once flourishing right bank was so badly affected that it remained a wasteland until the 19th century.

Despite the killing and destruction a considerable resistance movement against Mongol rule was maintained for some years throughout Khorezm and

Transoxiana. It was not until 1231 that Chin Timur, by then the governor of Khurasan and Mazandaran, succeeded in wiping out the last pockets of

resistance in his province.

Ghaznia, Khurasan, the Caucasus, and Qipchaq

Meanwhile Chinggis had embarked on the invasion of Afghanistan, crossing the Amu Darya to capture Balkh. It was probably here that Chinggis received

news from Jebei about the death of the Khorezmshah and the escape of his son Jalal ad-Din. To make matters worse Jalal ad-Din had quickly departed

from Gurganj with a small group of supporters, crossing the Qara Qum to reach Nisa. There he had overrun a small Mongol force specifically established

as part of a cordon to prevent the royal family fleeing to Khurasan. He was lucky - when two of his brothers followed the same route some time later

they were captured and beheaded.

After leaving Nishapur on 10 February 1221, Jalal ad-Din was detected and chased by yet another Mongol detachment, only escaping from them in

the vicinity of Herat. He now hastened eastward to reach the safety of Ghazna (modern Ghazni, south of Kabul), which was under the control of friendly

forces. Here he was joined by yet more of his allies and their supporters and soon found himself at the head of an army of 60,000 troops composed of

detachments of Qanqli, Ghurid, and mixed Khalaj and Turkmen forces.

That same February Chinggis entrusted Toluy with the conquest of Khurasan, a task that he accomplished with massive brutality. Travelling due west

Toluy crossed the Murghab to take the two small towns of Maruchak and Saraqs before totally devastating Merv. In April he annihilated Nishapur, went

on to capture Herat, and then returned in the early summer of 1221 to rejoin his father who was accompanying Mongol forces besieging the fort of Talaqan

between Merv and Balkh.

|

With the onset of spring Jalal ad-Din left Ghazna and moved northwards to Parvan (north of Kabul). There he attacked a nearby Mongol detachment that

by chance was in the same area. Hearing the news Chinggis immediately sent 30,000 men to Parvan, where they were thoroughly routed by Jalal ad-Din's

army. Rumours of Jalal ad-Din's successes reached Khurasan in the second half of the year and led to the outbreak of revolts. With Talaqin finally

overrun and the defenders massacred, Chinggis now set out for Ghazna himself, along with Chaghatay, Ögedey, and Toluy. After a one month delay

while they overcame heavy resistance on the route to Bamiyan, Chinggis and his sons arrived at Ghazna only to discover that Jalal ad-Din had departed

for the northern Indus two weeks earlier. The Mongols hastened eastwards, catching up with Jalal ad-Din's army somewhere near modern Kalabagh, just

as they were preparing boats to cross the river. Jalal ad-Din seems to have made the opening moves against the arriving Mongol forces but was caught

in a deadly counter-attack in which most of his forces were surrounded and destroyed. Sultan Jalal ad-Din put up a heroic fight and managed to escape

across the Indus on horseback, possibly heading for Peshawar with a small band of followers. Chaghatay attempted to follow the Sultan but lost his trail.

Chinggis subsequently sent another of his commanders with 20,000 men into the Punjab region of Pakistan to track the Sultan down. They too failed to

accomplish their mission. Jalal ad-Din would spend three years of exile in India before returning to Iran.

|

According to Nasawi the Battle of the Indus took place on 24 November 1221. It effectively marked the end of Chinggis Khan's campaign against

the Empire of Khorezm.

There is one fascinating tail end to the story. While the main Mongol army had been campaigning in Afghanistan, Jebei and Sübetey had entered

the Caucasus Mountains. They had spent most of 1220 criss-crossing northern Iran and although they had managed to overtake and destroy one of the

Khorezmian armies, they seem to have lost track of the Khorezmshah somewhere in the region of Hamadan. They decided to divide their forces,

Sübetey searching the eastern Elburz Mountains and Jebei the plains of Mazandaran. Little did Jebei know that his quarry was just a short

distance offshore from the Mazandaran coast. With the trail having gone cold, the two commanders reunited at Ray before searching out good pastureland

on the Mughan Steppe in southern Azerbaijan for the duration of the winter of 1220. It was there that they were joined by freebooting Kurdish and

Turkmen nomads who, in February 1221, guided them into the Christian Kingdom of Georgia. After numerous skirmishes the Mongol expeditionary force

decisively overwhelmed the standing army of King Giorgi IV. March saw a return to Azerbaijan, after which they were recalled to violently suppress

a revolt in Hamadan. In the autumn they launched a second violent attack on Georgia before entering the steppes to the north of the Caucasus Mountains

(today part of southern Russia) to overwinter their livestock.

Clearly either before departing Gurganj or sometime later they must have received authority from Chinggis Khan to reconnoitre this northern Caspian

steppe region. It was home to various local nomadic tribes including the As or Alans (Ossetians), Lesghians, Circassians, and Qipchaqs, who soon

engaged in battle with the mysterious new arrivals. Ibn al-Athir wrote that the Mongols were able to drive a wedge between the combined Qipchaq-Alan

tribes, persuading the Qipchaqs to form an alliance because of their ethnic similarity to the Mongols. Having overcome the various Caucasian tribes

in the region the Mongols then turned on the Qipchaqs, driving them towards the north-west.

Jebei and Sübetey must have spent the whole of 1222 engaging the Qipchaq nomads across the region. In January 1223 the Mongols reached the

commercial centre of Sudak in the Crimea, a colony of the small Greek Empire of Trebizond.

One of the Qipchaq leaders, Khan Koten, was married to a daughter of the prince of Galich. Out of sheer desperation he appealed to his father-in-law

for assistance. In May 1223 the princes of Galich, Chernigov, and Kiev gathered a large army to the west of the Dnieper. The Mongols responded by

sending envoys to the Rus, assuring them that they had no argument with the Rus themselves but only with the Qipchaqs (who were known to the Rus as

Polovtsians). The envoys were all massacred. After the Rus armies crossed the Dnieper they soon encountered the Mongols and a skirmish ensued, the

Rus capturing some of the Mongol herds. The Rus drove forwards, the ever-cautious Mongols retreating eastwards until they encountered the right

conditions to engage in battle. After eight days, on either 31 May or 16 June 1223, the Rus and Qipchaqs reached the Kalka River, to the

north of the Azov Sea. There was rivalry between the Rus princes and their armies were not coordinated. The Mongols had laid an ambush and when they

crossed the river to engage the Rus, chaos ensued. With the Rus totally overwhelmed the Mongols pursued the survivors back to the Dnieper, south of

Kiev, crossing to the west bank and sacking the town and surrounding area of Novgorod Svyatopolch. The Rus had been virtually annihilated, possibly

only one in ten surviving. In order not to spill royal blood the Mongols arranged for the princes to be suffocated.

The local Suzdalian chronicler who reported the battle claimed that the Mongols killed more fighting men than had ever been slaughtered before in one

battle. In the following year of 1224 the Chronicle of the Novgorod Feudal Republic reported:

" ... unknown tribes came, whom no one exactly knows, who they are, nor whence they came out, nor what their language is, nor of what race they are, nor what their faith is; but they call them Tatars."The Qipchaqs had also been destroyed as a military power and would never again pose a threat to the Rus.

|

At some time during the last years of his life, possibly at one or more such qurultais, Chinggis Khan publicly declared his decision to divide up his Empire into domains, or ulus, each one assigned to one of his four sons by his chief wife. He also allocated them yurts or personal tracts of pastureland, on which they could locate their orda or encampment. According to Juvaini:

"When during the reign of Chinggis Khan the kingdom became of vast extent he assigned to everyone his place of abode, which they call yurt."Like the yurts, the ulus consisted solely of the open steppe pasturelands. The cultivated lands, such as those around Bukhara and Samarkand, remaining imperial property. Each ulus was accompanied by an inju, annual revenue derived from the taxation of the sedentary territories to fund each son's court.

|

However it seems likely that the division of Chinggis's possessions was not a single event but evolved over time, each of the ulus changing

in location and increasing in size as the Empire expanded. For example "The Secret History" records that in 1207 Chinggis divided all the people

(of the Empire) between his mother, his surviving brothers, and his four sons by his chief wife. Also in 1207 and 1208 the Oyirat, Kyrgyz, and

northern Shibir tribes were allocated to Jöchi after his conquest of the forest peoples, as was the city of Gurganj in 1221. Clearly the

allocation of the lands of Khurasan, Khorezm, and the Syr Darya can only have taken place after their overthrow.

Juvaini reports that Jöchi received "the territory stretching from the regions of Qayaligh and Khorezm to the remotest parts of Saqsin and

Bulghar and as far in that direction as the hoof of the Tatar horse had penetrated." In other words, the steppes of Kazakhstan and southern Russia,

ranging westwards from present-day Almaty to the Volga and beyond. Under Mongol law the territory that was the furthest from the paternal residence

was reserved for the eldest son. Therefore Jöchi was bound to inherit the territories furthest from his father's homeland by the Three Rivers.

The second son Chaghatay was given territories "from the country of the Uighur to Samarkand and Bukhara and his place of residence was Quyas in the

vicinity of Almaliq." This essentially comprised most of East Turkestan (Xingjiang) and Transoxiana including the right bank of Khorezm.

Ögedey was given the Altai and western Mongolia. The youngest son always inherited the hearth or the homeland and so Toluy received central

and eastern Mongolia. Note that although the Mongols had invaded Iran and Afghanistan these were not included into the Mongol ulus at this time.

|

It is clear that Jöchi's domains are a retrospective assignment that cannot possibly have applied during Jöchi's lifetime. The territories to the west of the Aral Sea would only be subjugated later by Jöchi's descendants. It is more likely that Jöchi's ulus at the time of his death was along the lines given by Rashid al-Din in Part II of the "History of Jöchi Khan", namely:

"all the countries and ulus which lie in the region of the Irtysh [river] and the Altai mountains, and the summer and winter ranges in that area. ... His yurt (pasturage) was in the region of the Irtysh, and his residence was there..."

|

Chaghatay's personal ulus was originally south of the Ili (northern Kyrgyzstan and Xiangjian) according to Ch'ang Ch'un, who travelled through

that region in 1221 and 1223. During his father's lifetime Ögedey's personal ulus seems to have been in the valleys of the Emil

and Qobuq rivers, north of the Ili and south of the Altai. Juvaini recorded that Ögedey assigned this appanage to his eldest son

Güyük when he ascended the imperial throne in 1229.

It is of course likely that before or during the conquest of Khorezm, Chinggis had promised Jöchi and his brothers that their ulus would

be extended. Jöchi certainly seems to have been promised Gurganj and left bank Khorezm and may have also been promised the territories yet to

be conquered further west.

We know from Rashid ad-Din that Chinggis Khan had earlier ordered Jöchi to subjugate the peoples of the Qipchaq steppe and Siberia, including the

Bulghars, Bashkirs, Rus, Cherkes (Circassians), and Qipchaqs. The plan of the campaign required Jöchi to eventually rendezvous with

Sübetey's forces north of the Caucasus. Instead we are told that Jöchi deliberately disobeyed his father's orders and took no further

part in the Mongol campaigns. His father was furious, and threatened to kill him.

We have already seen that Chaghatay and Ögedey travelled south to join Chinggis at Talaqan before Khorezm had been completely subjugated,

subsequently assisting their father in the pursuit of Jalal ad-Din. By contrast Rashid ad-Din tells us that Jöchi left Khorezm to return to

his former ulus on the Irtysh river "where his heavy baggage was" (in other words for the encampment of his court from whence he had

originally set out for Khorezm).

Juvaini provides an apparently contradictory account suggesting that Sübetey and Jebei eventually linked up with Jöchi on the Qipchaq

steppe before returning to rejoin Chinggis Khan. Elsewhere Juvaini states that while Chinggis was wintering in Samarkand, he sent orders to Jöchi

on the Qipchaq steppes to set out to meet him, driving game (wild asses) before him. In the following spring Chinggis held a qurultai with

his three other sons on the east bank of the Syr Darya at Fanakat (not far from modern Tashkent), before heading on to Qulan Bashi. It was here at

Qulan Bashi that Jöchi "came up from the other side" (presumably the western bank) to rejoin his father with 1,000 grey horses and herds of

wild asses. We know of course that one of Jöchi's responsibilities was for the organization of the royal hunt.

Rashid ad-Din confirms that Chinggis summoned Jöchi "after departing from the Tazik country", in other words after leaving the Iranian

territories in late 1222. Jöchi was not able to present himself because of his illness and instead offered his excuses along with gifts of

game, perhaps to Qulan Bashi. Chinggis summoned him again on several subsequent occasions but without success. Although Jöchi apologized

that he was ill, Chinggis was given information, albeit mistaken, that Jöchi had been out hunting. Finally, sensing rebellion, Chinggis ordered

Chaghatay and Ögedey to lead their armies against him, not realising that Jöchi was now close to death. Chinggis was therefore angry

and aggrieved when he received news in China about the eventual death of his eldest son.

The popular interpretation is that after the disagreement at Gurganj, Jöchi had turned on his father and retreated back to his ulus

to sulk. There were clearly tensions below the surface. "The Secret History" hints that Jöchi may have been fathered by a Merkit rather

than Chinggis himself and this may have caused a divide between Jöchi and his other three brothers who did not regard him as an equal, worthy

of leadership. Chinggis's decision to put Ögedey in charge of the siege of Gurganj may have opened up old wounds and created a divide

between Jöchi and his father.

Juzjani is the only author to propose outright treachery. He writes that Jöchi returned to the Qipchaq steppes and fell in love with them.

In time he turned against his father and threatened to kill him, and even considered allying himself with the Khorezmians. Chaghatay got wind of his

idea and informed his father who consequently arranged for his son to be killed by poison. The story is absurd and no more than a figment of

Juzjani's anti-Mongol imagination.

The course of events was undoubtedly more complicated. Maybe Jöchi did not return to his yurt on the Irtysh directly but first set

out into the Qipchaq steppes to the north of the Aral Sea, planning to extend the boundary of his ulus towards the Emba and the Ural Rivers.

Possibly the onset of illness during 1223 forced him to change his plans. Jöchi may not have been disobedient to his father at all – the

problem seems to have been that his father did not believe his excuses. Certainly the hunt at Qulan Bashi seems to have gone ahead, organized by

Jöchi's ulus but without his direct participation.

Whatever the truth, Jöchi seems to have spent the last few years of his life in relative isolation, following a nomadic existence on the vast

steppes of Kazakhstan. He clearly suffered from a long mysterious illness (inconsistent with poisoning) before he died in early 1227 at the age of

47, just six months before the death of his father.

During his lifetime Jöchi had sired almost forty sons with his many wives and concubines. His eldest son Orda and his second son Batu had been

born by different mothers belonging to the Onggirat or Qon'irat tribe (the tribe of Börte, the mother of Chinggis's four chief sons). Orda and

Batu were followed in turn by Berke, Berkecher, Shiban, Tangqut, Bo'al, and Chilaqa'un, and of course by many more after that.

Juvaini tells us that at the time of his death Jöchi's six oldest sons born by his chief wives had all come of age (by Mongol standards). They

were in descending seniority: Ordu, Batu, Berke, Berkecher, Shiban, and Tangut. At that time Orda was about 23, Batu was about one year younger and

Shiban may have only been 12 or 13. Out of the six, Batu, the second son, was chosen to succeed his father and became the ruler of Jöchi's

kingdom as well as of his brothers. This decision was most probably made by the most senior tribal leaders from within Jöchi's ulus and

might have been endorsed by Chinggis Khan himself given the size of the territories under Batu's control. Rashid ad-Din says that Batu's brothers

tendered their allegiance to him and we know that all of Batu's brothers supported him faithfully over the following years. Batu's age and the cloud

hanging over his late father would mean he would have little influence over the governance of the overall Mongol ulus, at least in the short

term.

One major uncertainty concerns the question of whether Batu's ulus was segmented at this stage or at some time later. Unfortunately the

early histories of Juvaini and Rashid ad-Din provide us with no information. The one historical source that claims such a major segmentation took

place at this point is the Chingiz-Namāh, written by Ötemish Hajji in about 1550. This covers the history of the house of

Jöchi down to the late 14th century and claims that, before he died, Chinggis Khan distinguished three of Jöchi's sons. He established

three major territorial and tribal divisions within Jöchi's ulus, the White Horde of Batu, the Blue Horde of Orda, and the Grey Horde

of Shiban. However Hajji's work is very biased towards Shiban and his descendants. One way to fully legitimize the later Shaybanid dynasty would

have been to establish a direct line of authority back to Chinggis himself.

We think that it was unlikely that such a division was implemented at this time, taking into account the age of Jöchi's offspring and the massive

westward expansion of Jöchi's ulus that would take place only fifteen years later. We will return to this issue in the following

webpage – the Golden Horde.

Chinggis died of fever "arising from the insalubrity of the climate" (perhaps typhus) in August 1227 while exacting a violent revenge against the

Xi Xia. According to Rashid ad-Din his remains were taken back to his birthplace close to the Onon and Kelüren rivers and he was secretly

buried close to the Burqan-qaldun Mountain. However a few scholars such as Ratchnevsky have challenged this assumption, proposing that because of

the warm climate it may have been necessary for the funeral cortege to bury his corpse in the Ordos region of Inner Mongolia.

|