|

Contents

Intervention by Russia

Russian Annexation

Russian Khorezm

Repression and Dissent

Prelude to Revolution

References

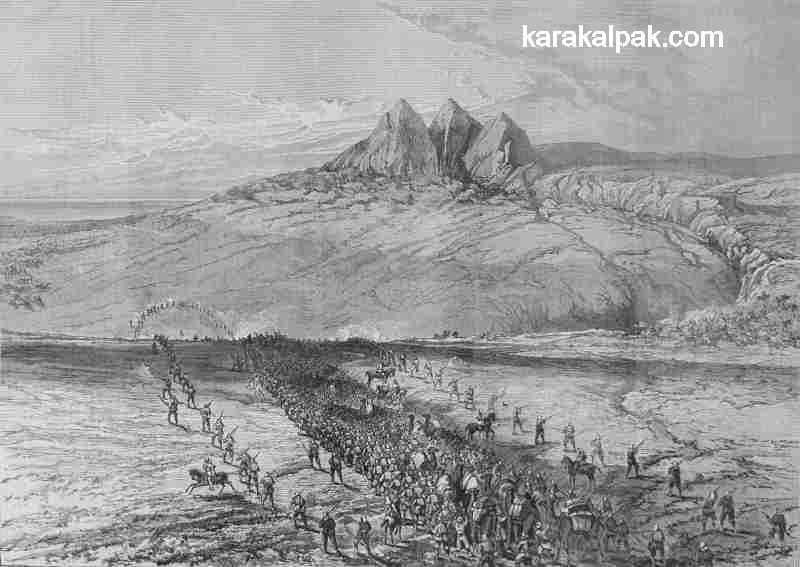

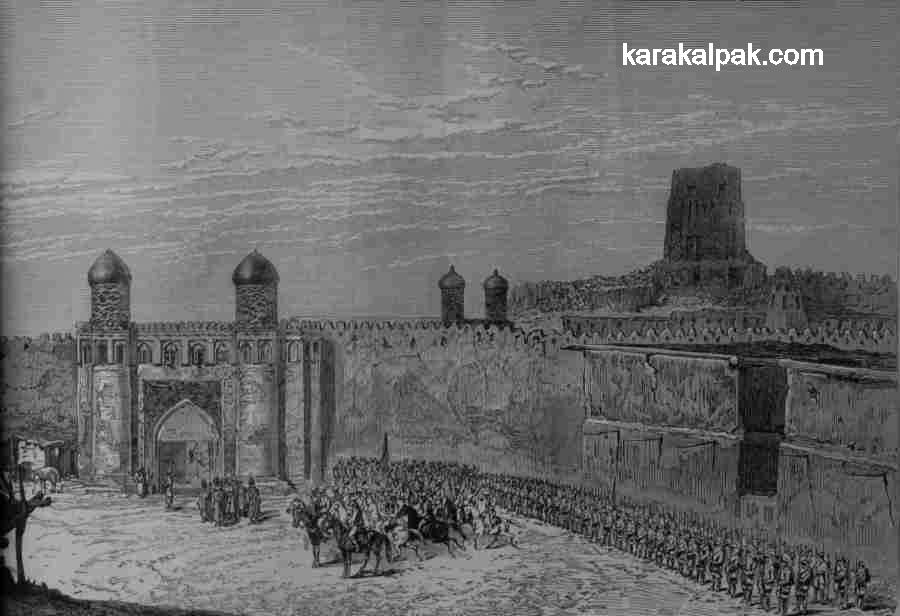

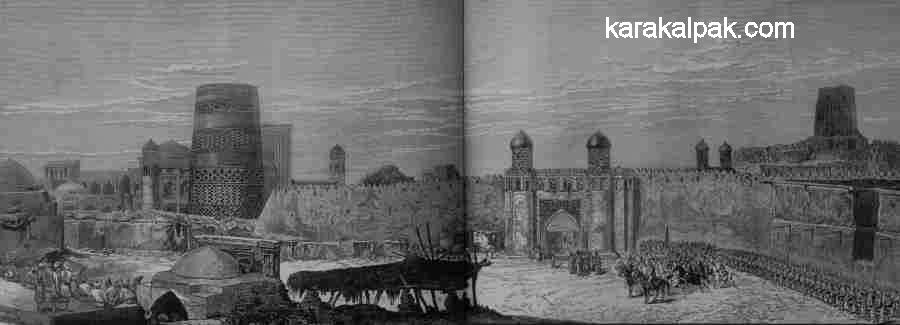

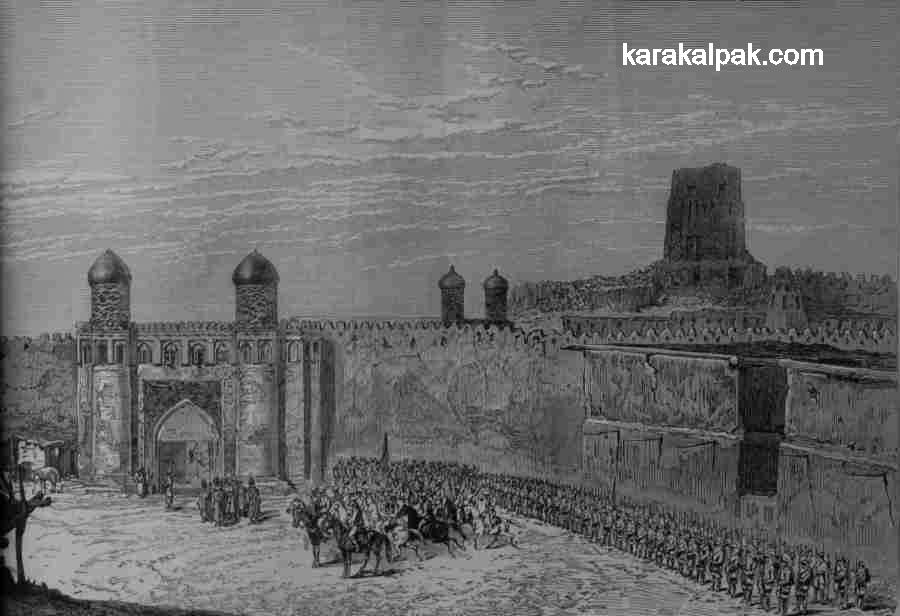

Russian troops entering Khiva through the Hazarasp gate.

From a drawing by N. N. Karazin published in the Illustrated London News, 22 November 1873.

Intervention by Russia

By now the British were well aware of Russian ambitions in Central Asia and of the possible risk to India. The Great Game was well under way with

British and Russian spies criss-crossing Central Asia to gather intelligence for their respective governments. The British sent Connolly to spy on

Khiva but his mission had to be aborted after robbers attacked him in the desert. "Bukhara" Burnes successfully reached Bukhara and Pottinger became

a hero after assisting Herat to overcome a siege by the Shah of Persia. The British were not quite so concerned about Persia gaining a foothold in

Afghanistan gunboat diplomacy was enough to warn the Persians off. Their real concern was Russia and in 1839 they decided to take control of

Afghanistan themselves, conquering Ghazni (ancient Ghazna) and establishing a garrison in Kabul. India was now protected by a formidable defensive

buttress.

Britain's increasingly aggressive stance had alarmed the Russians, who in any event had decided that the time was right to take Khiva. With the

approach of winter General Perovsky set out from Orenburg with a force of 5,000 men, 2,000 horses and 10,000 camels, under the guise of freeing the

Russian slaves. He was armed with 22 guns and a rocket battery. He had chosen this time of year to make sure that there would be sufficient water

for his men and animals, hoping to arrive in Khiva before the weather deteriorated badly. However 1839 turned out to have one of the earliest and most

severe winters in living memory. By January Perovsky was only half-way there, bogged down in snow and ice, losing men from frostbite and with

his camels dying at the alarming rate of 100 a day. On 1 February he gave the order to retreat but did not get back to Orenburg until May, his

progress and supplies being disrupted by the constant snowstorms and whirlwinds. He had lost 1,000 men and 8,500 camels and had not even fired a shot

in anger.

The British spy network had long ago passed news of the intended Russian mission back to London, and at the end of 1839 Captain Abbott had been sent on

a reconnaissance mission from Herat to Khiva, travelling via Merv. Abbott arrived in mid-winter with a message of friendship from the British Envoy at

Herat, along with modest gifts of firearms. He found Allah Quli Khan to be an amiable man, aged about 45, with a rather timid manner and a lack of

vigour. The Khan, fully aware of the Russian advance, was disappointed that Abbott had come without any offer of British military assistance. The Khan

was totally ignorant of Britain or its Empire, finding it hard to take a country with a female head of state seriously. It soon became clear to Abbott

that the Khivans had little concept of either Russian or British military power, or even of the general geography of Eurasia Abbott was amazed to see

the Khan refer to a local map on which Italy was located to the north of Britain and China was located to the north of Russia! After much questioning

and evasion Abbott discovered that the Russians had advanced from Orenburg to Emba and had then sent a detachment of troops forward to entrench

themselves to the north-west of the Aral Sea. Meanwhile the Khan had dispatched an army on horseback, ridiculously claimed to be 40,000 strong, up the

west coast of the Aral Sea, where they had encountered heavy snow. An advance party of Turkmen had attempted to seize the cattle from the advance post

of the Russians, only to have been spotted and picked off like flies by the Russian fusiliers. Meanwhile many members of the main Khivan army had been

mutilated by the intense cold and its commander had sought the Khan's permission to retreat to Qon'ırat.

Abbott argued that if Khiva was to seek British assistance it would first have to release all of the Russian citizens enslaved in Khorezm. However,

when the Khan asked for assurances that such a release would stop the Russian advance, Abbott was unable to offer anything in return. He had come to

Khiva on the spur of the moment, without even any credentials from the government of India. After some delay he finally departed empty-handed in late

March, travelling to Dashoguz, then across the Ustyurt to Novo Aleksandrovsk, up the Caspian and thence to Orenburg. Here he not only discovered that

the Russian invasion force had been recalled to Orenburg, but was introduced to, and entertained by, General Perovsky himself. Before leaving for

Moscow and Saint Petersburg, Captain Abbott also discovered that the Russians seemed to be making preparations for another assault on Khiva later that

year.

Meanwhile a young 28-year-old, Lieutenant Shakespeare, had been sent to Khiva to check on Abbott's progress, only to arrive after his departure.

Although the Khan was now in good spirits, having heard news of the Russian disaster, he was also concerned about what Russia would do next. By now

the local population were aware of the Russian advance on Khiva, news that the Khan turned to his advantage by spreading propaganda that the invaders

had actually been slaughtered by his own forces just north of Qon'ırat.

Lieutenant Shakespeare struck up a good relationship with the Khan and convinced him that the Russians would not give up because of Perovsky's failure

and would eventually send another expedition. His best defence was to release the Russian slaves and to issue orders forbidding the further capture

or purchase of Russians. Although the Khan was reluctant to act, the British officer finally persuaded him to release 416 Russian slaves into his care,

who Shakespeare subsequently escorted to General Perovsky in Orenburg much to the chagrin of Tsar Nicholas I, who had just lost one of his main

excuses for a further invasion.

The Tsar sent envoys to Khiva in 1841 and 1842, and a Colonel Danilevskiy finally succeeded in securing the first treaty between the two countries. The

Khivans promised not to engage in hostilities with Russia, or to commit acts of robbery or piracy - promises that were not worth the paper they were

printed on. However before Danilevskiy could leave Khiva, Allah Quli Khan died and was succeeded by his son, Rahim Quli (1842-46), who ruled for just

a few years.

Danilevskiy recorded various statistics on the province, which indicate its small size and dilapidated state at that time. The population of Khiva was

about 4,000, virtually all Sarts, while the population of (New) Urgench was about 2,000, composed mainly of Sarts and a few Uzbeks. The rectangular

wall around the latter city was in ruins with only the corner towers and two collapsed stone gates remaining. The town had 300 houses, 15 mosques, 2

medressehs and 320 shops. Shahabad had a house for the Khan with a garden, one mosque, up to 100 shops and some private houses. The walls were in

ruins in many places. Gurlen had no wall at all and was densely built with 60 shops and three main mosques. The town of Kath had a rectangular wall,

now in ruins, a single gate from the east, 50 houses and 40 shops, and no population the town was deserted.

The major reconstruction of Khiva that had begun under Muhammad Rahim had continued under Allah Quli Khan. He built the majolica-tiled 163-room

Tash Hauli Palace in 1830-32 using the best craftsmen available in Khorezm and the Allah Quli Khan Caravanserai and Bazaar nearby, although it is likely

that Persian slaves did all of the hard work. The interior of the Kunya Ark was refurbished with a new mosque, and work began on the Allah Quli Khan

and several other Medressehs. The defences of the Ichan qala were improved with the western Ata Darvaza (Master Gate) and the southern Tash Darvaza

(Stone Gate), being rebuilt. The expansion of the city can be gauged from the need to build a new 6½-kilometre-long outer rampart around the

outskirts of the town - the Dishan qala entered by means of ten gates. Its purpose was to defend Khiva against Yomut Turkmen raids. Residents of the

town were forced to work unpaid for 12 days a year to assist in its completion.

Allah Quli Khan was also responsible for building a brick palace at Dashoguz with a royal garden, close to the stone-encircled pond from which the town

derived its name. Its purpose was to provide him with an overnight stopping place. Dashoguz was a walled town with three gates: the west, the south

and the palace gate. It contained a mud-brick fort. Surrounded by rich farmland it was already a large residential centre with six mosques, many shops

and workshops and a caravanserai.

The rapid development of Khiva at this time is evident from a secret map drawn by a Russian topographer, G. Zelenin, who arrived in Khiva with one of

the delegations of ambassadors in 1841. Given Khivan suspicions about future Russian intentions, Zelenin had to produce his map undercover. Had he been

caught his party would never have survived to tell the tale. It is said that he purchased two melons from the bazaar and wandered the town asking people

about the names of the streets and lanes and the mosques and medressehs, secretly inscribing this information on the melon skins so that it could be

transferred to his map in the evenings. The map showed the outer city wall was pear-shaped with the stem pointing westwards. The inner city was

rectangular, 600 metres from east to west and 400 metres from north to south. The city then had 17 mosques, 22 lanes and 260 merchants' stalls along

with medressehs, bazaars and caravanserais. Gardens, country estates, irrigation networks, fields and roads extended beyond the outer city walls.

Despite the major setback of Perovsky's mission, the Russian encirclement of Central Asia was gradually progressing. The earlier Russian forts along

the eastern Caspian coast had been quickly abandoned after the demise of Bekovich's mission, so new garrisons were needed in the region. The

construction of Fort Novo Aleksandrovsk had begun in Tsarevitch Bay on the eastern Caspian shore in 1833 and was followed by the construction of a chain

of forts to the south-west of the Aral Sea, giving Russian forces increasing control of the Ustyurt. Fort Aleksandrovsk was later relocated to the

western tip of the Mangishlaq peninsula. In 1847 the Russians built Fort Raim, a small hilltop fortification close to the mouth of the Syr Darya, which

became the base for the new Aral Flotilla, established to undertake research work on the Aral Sea and its two river deltas.

|

View of hilltop Fort Raim from the shipyard on the Syr Darya.

A watercolour painted by Taras Shevchenko in the summer of 1848.

From there Forts Number 1, 2 and 3 were built upstream along the Syr Darya over the next few years: Fort Number 1 was built at present-day Qazaly

in 1851, Fort Number 2 at Joudali in 1852 and Fort Number 3 at what is now Qizil Orda in 1853. However the initial location of Fort Raim (which

subsequently became Aralsk) turned out to be an unsuitable one at that time, being subject to frequent flooding. In 1855 its garrison was moved to

an enlarged fort built on the site of Fort Number 1, which subsequently became known as Fort Kazalinsk. Fort Number 3 eventually became known as Fort

Perovsky. Though sufficient for Central Asian requirements, these forts were fairly primitive by Western standards, with earthen outer walls and

ditches defended with light artillery, enclosing barracks, workshops and housing for senior officers.

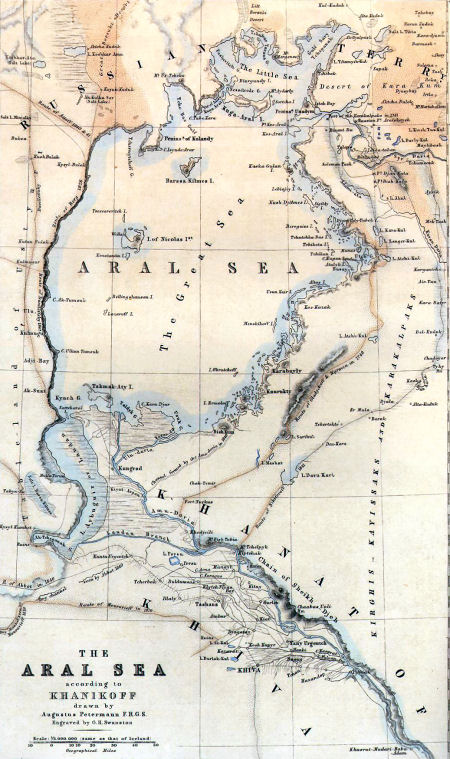

The initial fleet of the Aral Flotilla consisted of two twin-masted schooners, the warship "Nikolay" and the merchant ship "Mikhail", both constructed

in Orenburg in 1847. The first was designed for surveying and the second for establishing a fishery, but neither were capable of safely venturing far

onto the Aral Sea with its perilous shallows, and they became restricted to surveying the island of Qosaral in the mouth of the Syr Darya estuary and

the other islands down the eastern coast of the Aral Sea. Soon a somewhat larger schooner, the "Konstantin", was built in Orenburg and was used by

Lieutenant Aleksey Butakov to undertake the first complete survey of the Aral Sea in 1848 and 1849. The largest island in the centre of the Aral Sea

was discovered in September 1848 and was named Nicholas 1st Island, in honour of the Tsar. Nasledinik, or Heir Island was discovered seven miles to

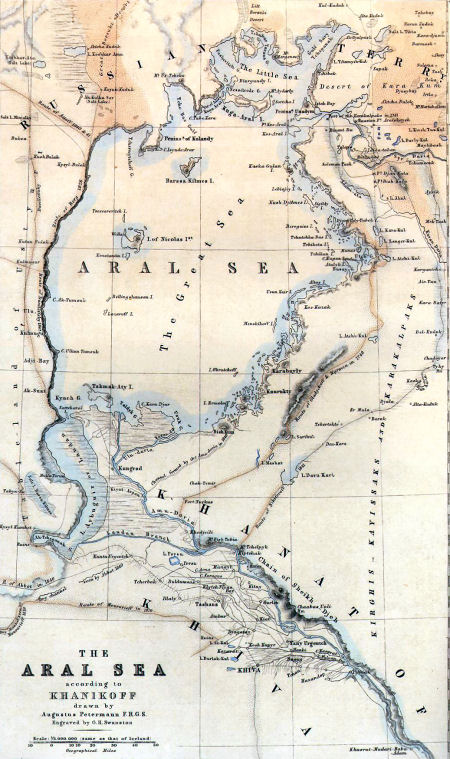

the north-west of Nicholas 1st Island, along with Konstantin Island to its south. Butakov's "Survey of the Sea of Aral" provided the first

scientifically produced map of the Aral Sea and its environs, which was subsequently copied by Augustus Petermann in London for the Journal of the

Royal Geographic Society in 1853, and was then reproduced commercially as a coloured lithograph.

|

Lithographed map of the Aral Sea based on the first Russian survey in 1848-49.

Copied by Augustus Petermann for the Journal of the Royal Geographic Society in 1853 and then reproduced commercially.

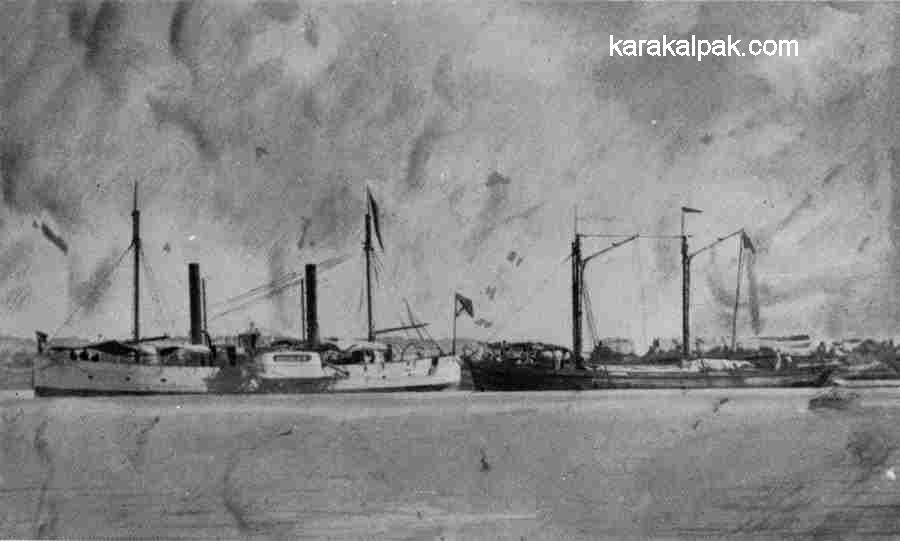

In 1850 the Russians ordered the construction of two new boats from a Swedish shipyard the "Perovsky", a forty horsepower paddle-wheel steamboat,

and the "Obrutchef", a twelve horsepower propeller-driven iron barque. The "Perovsky" was launched at Fort Raim in 1853, two years ahead of the

"Obrutchef", and was armed with three nine-pound guns. However it proved to be too large for navigating the more difficult parts of the Syr Darya

and was continually running aground. In a whole season it could only make three round trips between Fort Kazalinsk and Fort Perovsky. Both steam

boats required huge quantities of saxaul to fire their boilers and on one occasion 180 tons of anthracite was especially transported overland from the

River Don at enormous cost!

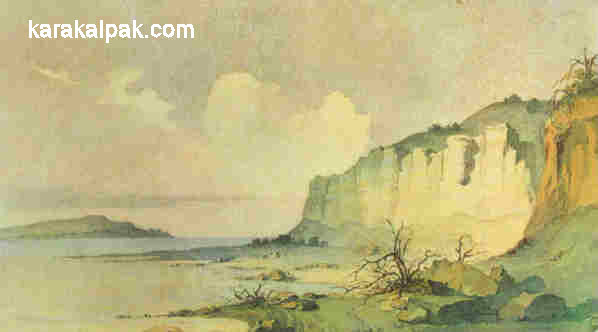

Although something of an aside, there is a very interesting human story associated with the early Aral Flotilla. In 1847 a Ukrainian poet and painter,

Taras Shevchenko, was arrested in Saint Petersburg for sedition by the Tsar's secret police. Although Shevchenko had been born into serfdom, he was

fortunate to have been contracted to a master painter in Saint Petersburg while still a teenager, and there he received a rigorous training in drawing

and art. Clearly a talented all-rounder, Shevchenko was not only a gifted painter but also a prolific poet, and soon attracted a group of admirers and

supporters who eventually bought him his freedom when he was 24-years-old. Seven years later he moved to Kiev and became associated with a society of

liberals who wanted an end to feudalism, and independence for the Ukraine today he would be regarded as a human rights activist. However the real

cause of his downfall was not his politics but his satirical poetry none other than Tsar Nicholas himself regarded Shevchenko's poems as a personal

insult and condemned the poet to military service for life, without promotion, expressly prohibiting his engagement in any further writing or drawing -

a terrible indictment for such a brilliant artist. He was sent on a forced march from Saint Petersburg to Orenburg where, by good fortune, General

Perovsky assigned him to the Academician Karl Ernst von Baer, a Baltic-German naturalist. Von Baer was a rising star in the Academy of Sciences in

Saint Petersburg and was becoming increasingly influential in the exploration of the new Russian territories, specializing in lakes and fisheries. As

such he had been selected to undertake the first scientific expedition of the Aral Sea on the newly built "Konstantin", under the command of Lieutenant

Butakov.

|

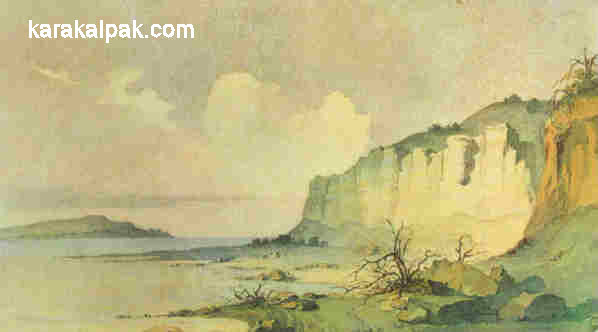

The cliffs, known as the tchink, bordering the western side of the Aral Sea.

A watercolour by Taras Shevchenko, painted in 1848-49.

Although officially no more than a common sailor, Shevchenko was tasked with sketching the various landscapes around the coast of the Aral Sea, including

the local Qazaq nomads, and was effectively treated as an equal by the other members of the expedition. After a voyage of over eighteen months he

returned with his album of drawings to General Perovsky at Orenburg, who was impressed with his work and sent a positive report to Saint Petersburg

hoping to obtain some amelioration in Shevchenko's punishment. The response was quick and severe. Perovsky received a sharp reprimand and Shevchenko's

punishment was increased to imprisonment. He was sent to one of the worst penal settlements, the remote fortress of Novopetrovsk, where he spent six

terrible years of mental and physical torment. Yet even here he managed to write and draw and, thanks to the efforts of his supporters in Saint

Petersburg, was finally released in 1857 following the death of Tsar Nicholas and the succession of the more liberal Tsar Aleksandr II. Today

Shevchenko is regarded not only as the National Poet of the Ukraine, but also as an important voice of freedom and independence by the formerly oppressed

peoples of Eastern Europe. Fortunately for us many of his simple and atmospheric sketches were preserved along with much of his poetry, some of it

written at the Russian fort on the island of Qosaral in 1848 and 1849. His lovely paintings give us our earliest visual impressions of the appearance

of the Aral Sea in the middle of the 19th century.

The construction boom in Khiva continued under Muhammad Amin Khan (1846-55) who decided to leave his mark on the city by building the tallest minaret

in Central Asia 70 metres tall. But he started too late and the minaret was only partially built when he died. Thus, by the hand of fate, his memorial

became not the tallest but one of the shorter minarets in Central Asia the Kalta Minar perhaps one of the most memorable buildings in the city. Like

his predecessors, Muhammad Amin continued the tradition of raiding Khurasan, Bukhara and the neighbouring Turkmen tribes, all paid for by taxing the

Sarts and Karakalpaks. He eliminated the threat from the local Yomut Turkmen by building dykes to divert the flow of the Darya Lyk, forcing them to

relocate to the Balkan Mountains. After six campaigns he finally subjugated the Saryk Turkmen at Merv and then led three bloody campaigns against the

Tekke between the Merv and Akhal oases, with help from the Yomut. To keep the Turkmen in check a garrison was established composed of Uzbeks and Yomuts,

but the local chieftains argued and the Yomut leader returned to Khiva, where the Khan had him thrown from the top of a high tower. This alienated the

Yomut who then formed a secret alliance with the Tekke! When Muhammad Amin next set out against the Turkmen in 1855, his army suffered a crushing defeat

at the hands of Tekke Turkmen, somewhere in the region of Merv or Saraqs, and the Khan was decapitated.

This triggered an uprising of the Yomut Turkmen in Khorezm, and Muhammad Amin's son Abdullah Khan faced challenges to his position both from his great-

uncle and from princes supported by the Yomut. Within five months he was killed in a skirmish with rebellious Yomuts and was succeeded by his younger

brother, Qutlugh Murad.

The Yomuts sued for peace and offered to release the Khan's cousin, whom they had captured in battle and had proclaimed Khan. Qutlugh Murad accepted

the offer, not realising that it was a plot. On the appointed day the Yomut appeared in Khiva with a force of supposedly 12,000 men (surely a huge

exaggeration) and as the Khan received and embraced his cousin he was treacherously stabbed to death. News of the incident was broadcast from the walls

of the citadel, and the incensed population rose up and massacred all of the Yomuts within the city walls. It was said that the streets ran with blood

and that it took six days to dispose of all of the bodies.

With Muhammad Amin's only two sons now dead, the crown was offered to one of his uncles, the one who had challenged Abdullah Khan. But the uncle was an

opium addict, incapable of fulfilling the role, and he abdicated in favour of his younger brother, Sayyid Muhammad Khan (1856-1864).

It was a time of crisis for Khorezm the civil war between the Uzbeks and Turkmen had devastated Khiva and the surrounding regions, and the wives and

children of the warring factions had been taken into slavery. The instability had provided an opportunity for the Karakalpaks in Khorezm to rebel, with

the Qon'ırat and On To'rt Urıw tribes uniting and encouraging the Qazaqs and Uzbeks from northern Khorezm to join their cause. When the insurgents appealed

to the Qazaqs along the Syr Darya, the new Khan realised he needed to take drastic action and he negotiated a truce and alliance with the Turkmen

leaders. The rebellious Karakalpak villages were routed and at a major battle near Xojeli, Sayyid Muhammad managed to defeat the combined insurgent

forces, finishing off the survivors after a three-month siege close to the Aral coast. The local population were in a desperate condition, suffering

poverty, exhaustion, huge price inflation, unreasonable taxation, instability and repression and in 1857 there was a major famine in the countryside

followed by a cholera epidemic. Many Karakalpaks fled the Khanate to seek refuge in Bukhara, the Syr Darya and the Russian territories to the north-west.

Appeals to the local authorities in Orenburg for protection received no response.

|

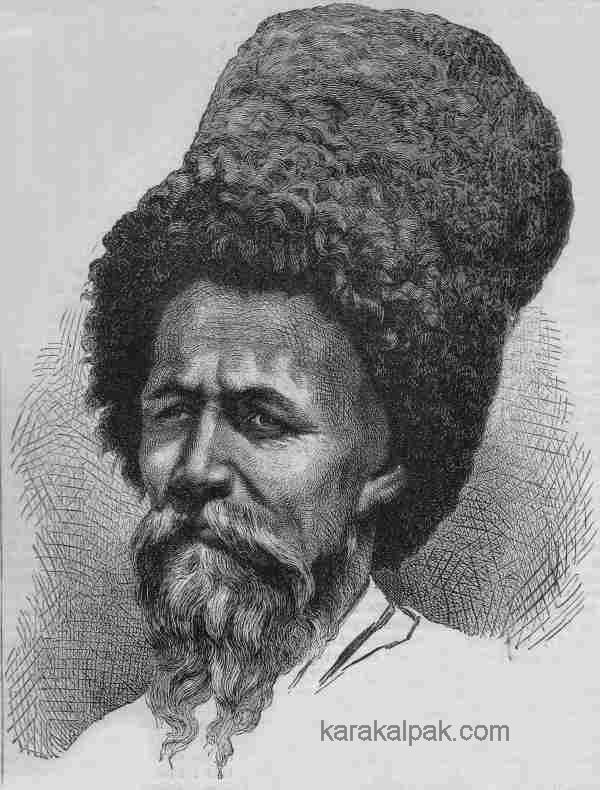

Ernazar Alako'z, nicknamed "big eyes", the leader of the 1856 Karakalpak uprising.

Painted by Barlıqbay Aytmuratov in 1988-91. From the collection of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

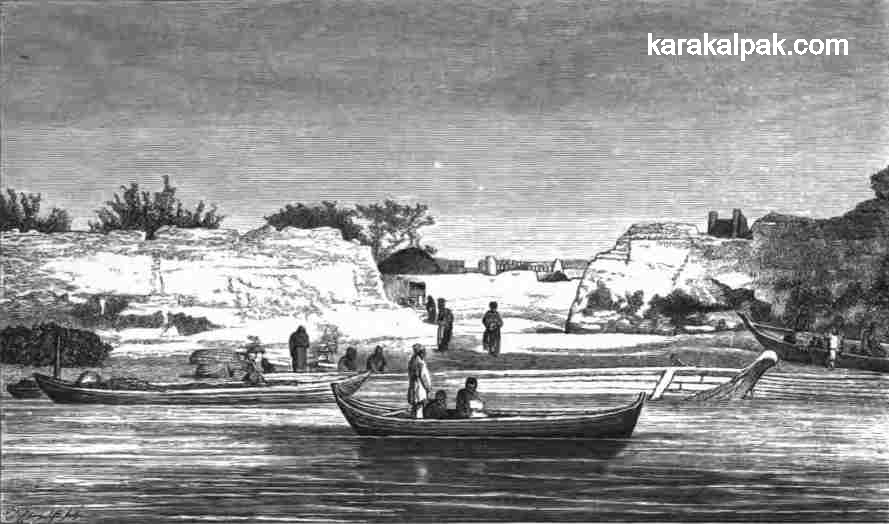

However the Russians did intervene in 1858, but for a different purpose. Having recently suffered defeat in the Crimean War, Russia was seeking to

increase its influence in Asia at the expense of the British. The new Tsar, Aleksandr II, had dispatched a mission to Khiva and Bukhara under the

leadership of the young Russian aristocrat N. P. Ignatyev, aimed at cementing friendships, increasing trade, surveying the geography and gaining

navigation rights for Russian ships on the Amu Darya. The embassy travelled overland from Orenburg, crossing the Ustyurt to reach the western shore

of the Aral Sea. They had planned to rendevous with the Aral Flotilla in Chernyshevskiy Bay and to then sail as close to Khiva as possible, using the

pretext of delivering lavish gifts to the Khan including a huge organ that had been transported across the steppes from Orenburg! However Captain

Butakov had become completely lost along the marshy shoreline of the Aral Sea and only reached Qon'ırat after the mission had departed by native boat

for Khiva. Nevertheless the paddle steamboat "Perovsky" along with its two attendant barges brought in vital supplies for Ignatyev and offered refuge

in the event of trouble. However its arrival caused alarm within the Khanate and the Khan refused permission for it to sail beyond Qon'ırat,

preventing a scientific survey of the lower Amu Darya.

|

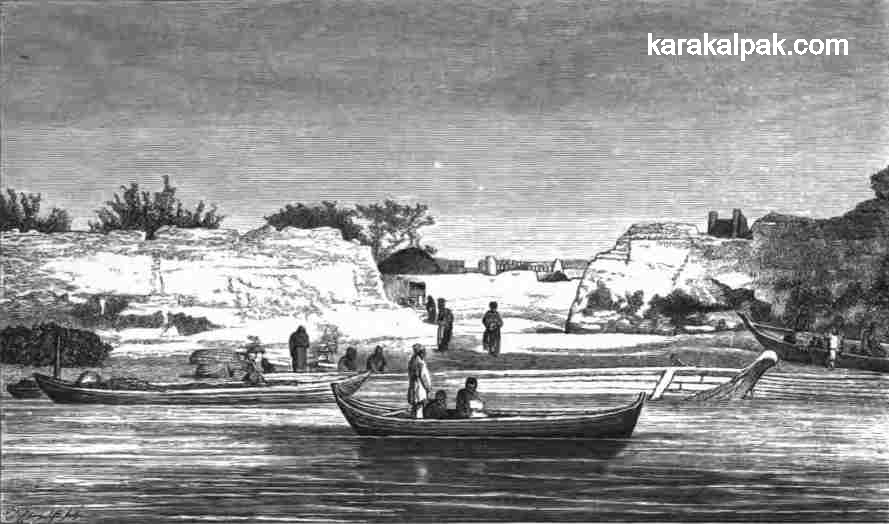

Part of the city of Qon'ırat from the Amu Darya.

Reproduced from Kühlewein's 1858 account of the Russian diplomatic mission.

An etching of the SS "Perovsky" and a barge moored opposite Qon'ırat.

Also from Kühlewein's 1858 account and remarkably similar to the photograph shown below.

Thanks to Kühlewein, the secretary to the mission, we have an account of the state of the left bank Karakalpak territory that the

embassy passed through on its way to Khiva, devastated by the Turkmen forces of the Khan during the recent civil war:

"Almost all the villages and towns were in a deplorable condition, presenting ample evidence of the devastations of the Turkmen. In the ruined "auls"

or camps of the Karakalpaks, we only found old people and infants; the whole of the adult population had been carried away to Khiva, and across the

Persian frontier, to be sold as slaves. The towns of Kipchak on the left bank of the Amu-Daria, and Hodjeil, had met with a similar fate."

Ignatyev spent six weeks in Khiva and found Sayyid Muhammad Khan extremely nervous. The Khan was highly suspicious of the Russian's motives, worried about

the presence of an armed steam-driven naval boat and alarmed by the obvious mapping of his territories. Reading between the lines, one suspects that the

Khan might have come close to having the embassy massacred, but probably decided that he had enough enemies already without adding Russia to the list.

Ignatyev's group spent a very tense time in Khiva, being kept under armed guard at all times. The local residents cursed them and made threatening

gestures and they were deliberately kept awake at night by loud drums and music.

The SS "Perovsky" and a barge moored below the walls of Qon'ırat.

Photographed in July 1858 by A. S. Murenko, a subaltern attached to Ignatyev's diplomatic mission.

Sayyid Muhammad clearly trusted none of his officials, had not the faintest idea of how to deal with a diplomatic mission, and was afraid of being

assassinated like his predecessor. After numerous rounds of fruitless talks Ignatyev decided to wind-up his mission, but late at night prior to his

departure he was summoned for one last audience with the Khan. Aware of the personal danger, yet determined to show the Khan that he was not afraid,

Ignatiev dressed in full uniform and organized an accompanying detachment of his roughest and toughest Cossack guards, each armed with two loaded

revolvers. As he approached the gates of the Palace, a bonfire illuminated two enormous stakes on which two of the Khan's prisoners had recently been

impaled. The meeting with the Khan was sharp and acrimonious and the ambassador withdrew with his Cossack guards holding back the Khan's bodyguards

with drawn revolvers. It was therefore with considerable relief that Ignatyev departed for Bukhara, even though no agreement had been reached during

his mission. This expedition clearly demonstrated to the Russians that diplomacy alone was not enough to establish a foothold in the Khanate.

After the Russian Flotilla had departed the Khan arranged for the leaders of the northern insurgents to be killed. Qon'ırat was soon back under

Khivan control.

|

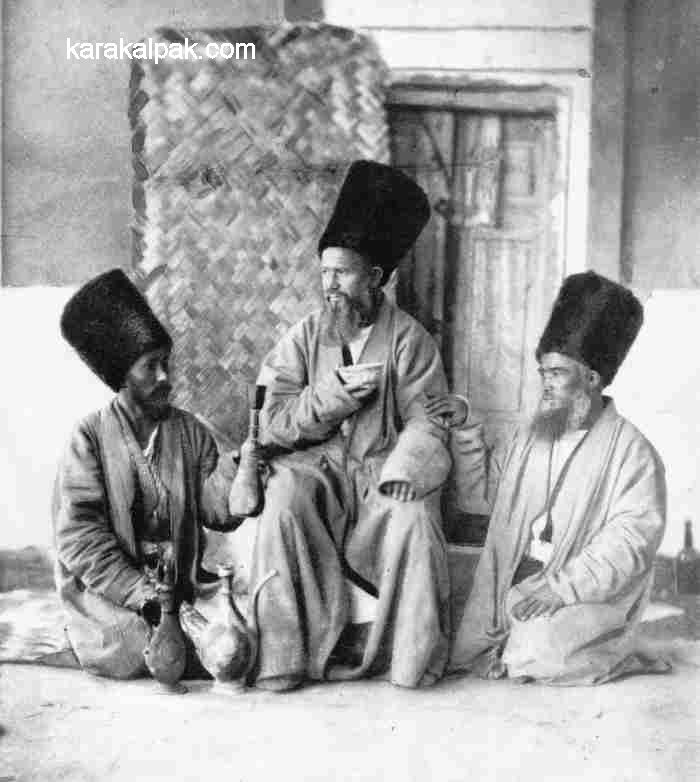

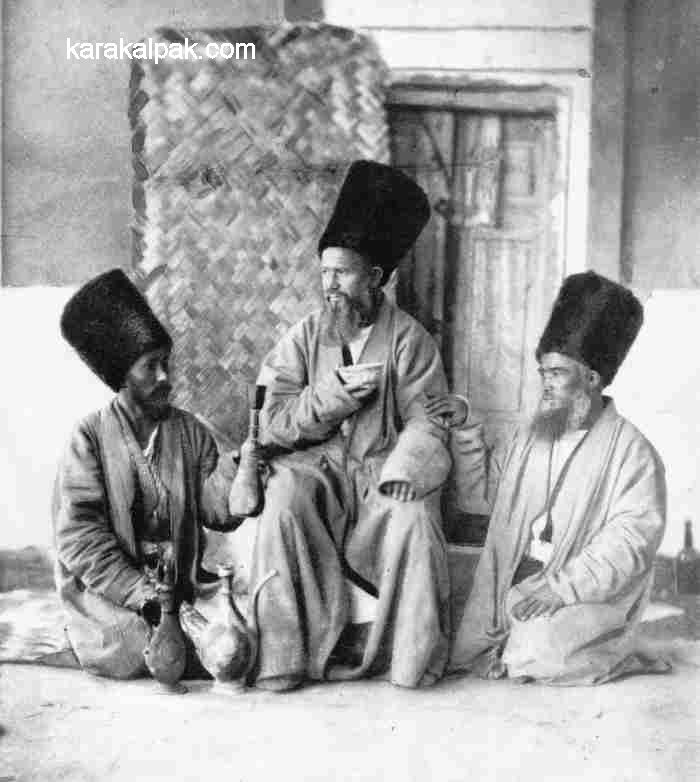

Three Khivans drinking tea in the courtyard of their home.

Photographed by A. S. Murenko in 1858.

The Hungarian professor of Oriental languages, Arminius Vambery visited Khorezm in 1863, thinly disguised as a Muslim Dervish from the Holy Land. Had

his disguise been uncovered he would at best have been enslaved as a Russian spy or at worst tortured and killed. Fortunately his audience with Sayyid

Muhammad Khan was uneventful and by now the Khan looked decrepit, having deep-set eyes, a chin thinly covered with hair, white lips and a trembling voice.

Yet Vambery knew he was a cruel and sick tyrant, daily disfiguring and executing his subjects often for minor transgressions. Vambery recorded that

there were many ha'wli farmsteads in the environs of Khiva, shaded by poplar trees and surrounded by meadows and rich fields. From a distance

the domes and minarets of the city "made a tolerably favourable impression" but its interior was even worse than a Persian city of the very lowest rank.

The bulk of the city consisted of a ten-foot high mud wall surrounding three or four thousand randomly arranged mud houses with uneven unwashed walls.

The bazaars were disappointing but there was a covered market, or Tim, with 120 shops selling cotton, linen, hardware, bread, groceries, soap and candles,

along with a caravanserai and customs post, which also served as the slave market. There were of course the monumental buildings within the Ichan qala,

but Vambery listed only four mosques of any antiquity or artistic construction, including the Pakhlavan Mosque and the Juma (or Friday) mosque, the

latter used by the Khan on a Friday. Only five medressehs had courts that could be classified as clean.

During his sojourn Vambery managed to travel down the Amu Darya to Qon'ırat and back and was astonished at the great fertility of the countryside

along the banks of the river, which he thought superior to anything he had hitherto seen in Asia. With the exception of the desert region around the

Sultan Uvays Dag, the land was well-cultivated and peopled, but in the delta where the Karakalpaks lived the riverbank was covered with "primeval forest":

"In the less thickly-wooded parts graze numberless herds of cattle, the property of the Karakalpaks, who find abundance of game in the forests, but

sometimes suffer greatly from the numerous wild beasts, especially the panthers [sic], tigers and lions [sic], which infest the district."

Vambery observed that the main crops grown in the Khiva Khanate were wheat, rice, low-grade Karakalpak barley used for horse feed, jugara, and millet,

along with peas, beans and lentils. The best fruits were melons, apples and sweet grapes. The region produced the best quality cotton of all of the

Khanates, as well as qendır or hemp, grown for low-quality linen, with a little silk grown in Khiva and Hazarasp. The Karakalpaks were

said to raise the finest cattle.

In fact Russia was increasingly in need of Khorezmian cotton at this time as a result of the world shortage brought about by the American Civil War. More and more

land was turned over to cotton production during the early 1860s to satisfy this demand.

Turkmen insurrections continued until 1867, at which point the Khanate lost control over the Turkmen tribes in the south. During these uprisings large

portions of the lands irrigated earlier in the century became devastated and abandoned.

Russian Annexation

By now the British response to Russian expansion in Central Asia had become more subdued. Although Britain had defeated Russia in the Crimea, she had

faced several setbacks of her own. Afghan resistance had led to the massacre in the Khyber Pass and a British withdrawal from central Afghanistan, there

had been a major army mutiny in India, and Russia had outmanoeuvred Britain and France by concluding a treaty with China. The Russians now had 300

steamships on the Caspian, a railway from Saint Petersburg to the Volga and an extensive network of garrisons controlling the whole of the Syr Darya

valley and the lands to the south of Lake Balkash. In 1867 the newly acquired Russian territories were designated Turkestan and were placed under the

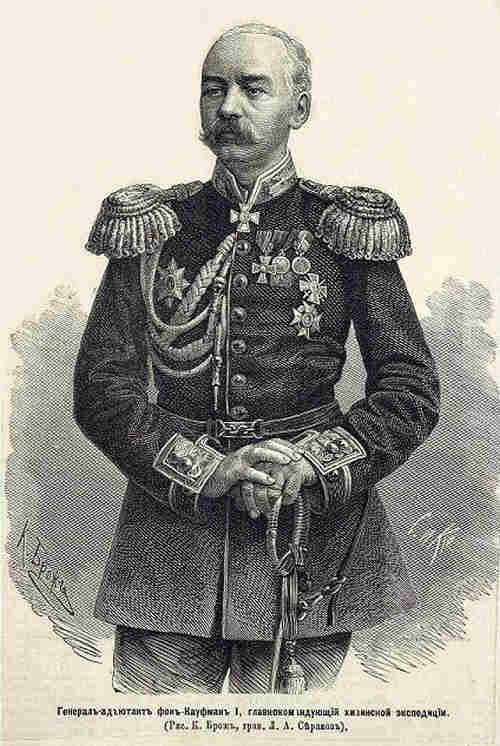

control of a newly appointed Governor General, General Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufmann. Russian Turkestan initially had just two provinces or

Oblasts, named Syr Darya and Semirechye.

Adjutant-General Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufmann (1818-1882), first Governor-General of Russian Turkestan.

From the Turkestan Collection in the Navoi State Library, Tashkent.

The time was right for Russia to expand its interests in the region. Surprisingly, the first major step was not initiated by Saint Petersburg but came

from an enterprising local Russian commander who exploited the opportunity to intervene in Khokand in 1875 while it was under attack from the Emir of

Bukhara. The Russians not only managed to capture the entire Khanate of Khokand but also its very important protectorate, the town of Tashkent. By the

time that Bukhara had reassembled its forces in Samarkand for a counter attack, several years later, it was pre-empted by the Russian army and the Emir

of Bukhara was forced to surrender. Renamed the Ferghana Oblast, the new territory was added to Russian Turkestan the following year.

Shortly after his appointment in 1867 General Kaufmann had immediately attempted to negotiate a treaty of friendship with the Khivan Khanate. Khiva was

now under the control of a new Khan, Sayyid Muhammad Rahim Bakhadur Khan II (1864-1910), known as Madrimkhan to his people. Kaufmann requested the release

of Russian slaves, the ending of Khivan support for Qazaq rebels and a trade pact, but the Khan and his officials replied with contempt and stepped up

their anti-Russian activities. Khiva was petulant because it felt genuinely aggrieved by what it saw as Russian incursions into its own territory,

delineated by the Syr Darya and the eastern coast of the Caspian. Ironically the time was right for negotiation, especially since Saint Petersburg was

in favour of a peaceful resolution to these problems and did not want to antagonise the British by embarking on another military campaign. But Khiva had

no experience of international diplomacy and dismissed the Russian threat. For many decades past the Khivans had thought that the Russians might invade

one day, but that day had never come. They began to believe that their remote location guaranteed them invulnerability. Kaufmann reported back to his

superiors in 1870 that military action would be unavoidable and he was recalled to Saint Petersburg. It is reported that at a meeting of the special

council, Tsar Aleksandr turned to Kaufmann and said, "Konstantin Petrovich, take Khiva for me!"

Military planning for the eventual annexation of the region now got underway. Kaufmann was an engineer as well as a soldier and military governor. He

began to plan his campaign in enormous detail. Well aware of the failures of the past, Kaufmann decided the best time for an invasion would be in the

spring. To minimise the risk, it would be best to use several separate invasion forces approaching from different directions, not only in case one or

more failed to make the hazardous journey but also to prevent escaping bands of Khivans forming alliances with Qazaq or Turkmen nomads. The strategic

Russian bases for launching the attack were virtually in place. In 1869 a secret naval expedition had established a stone fort in Krasnovodsk Bay, and

had established three military positions further south the following year. From here, reconnaissance missions explored as far inland as Qizil Arvat in

the south and Sarykamysh in the north, despite fierce opposition from local Turkmen tribes. In 1871 the Russians occupied Chikishlar close to the mouth

of the Atrak River at the south-east corner of the Caspian Sea, which then became the headquarters of the Russian Trans-Caspian forces in the region.

One of the most amazing achievements of the Russians at this time was the build-up of the Aral Flotilla at Kazalinsk (now Qazaly), which would assist with the

invasion. By 1873 this consisted of three side-wheel paddle steamers, the "Perovsky", "Samarkand" and "Tashkent", two stern-wheel steamers, the "Aral"

and the "Syr Darya", both armed with nine-pound guns, a steam launch, and many barges including three that were schooner rigged. The two stern-wheelers

were flat-bottomed and were constructed by the Hamilton Works in Liverpool in 1861. The individual parts were shipped to Orenburg, carried across the

steppes by camel an incredible feat of transportation and then finally assembled into boats at Kazalinsk. However they turned out to be less

satisfactory than the earlier steamboats, partly due to the poor quality of their final construction. The later "Samarkand" was built in Belgium in

1866 and the most recent "Tashkent" made in Russia in 1870.

Though alarmed at Russian developments, London and Calcutta felt that Russian domination of Central Asia was now inevitable, especially having received

intelligence about the new Russian fort at Krasnovodsk. When Muhammad Rahim Khan sent an embassy to India to request British assistance, Calcutta

recommended he comply with Russian demands. London's concerns were further allayed when the Russians conceded to the British position concerning the

location of the northern Afghan border and acknowledged that Afghanistan fell within Britain's sphere of influence. However this was just a clever ploy

to disarm the British - Tsar Aleksandr had already approved the plan to attack Khiva. But, to allay British fears over India, he had decided that there

would be no annexation of the territory and once the Khan had been punished and subjugated and the slaves had been released, Russian troops would leave

the Khanate.

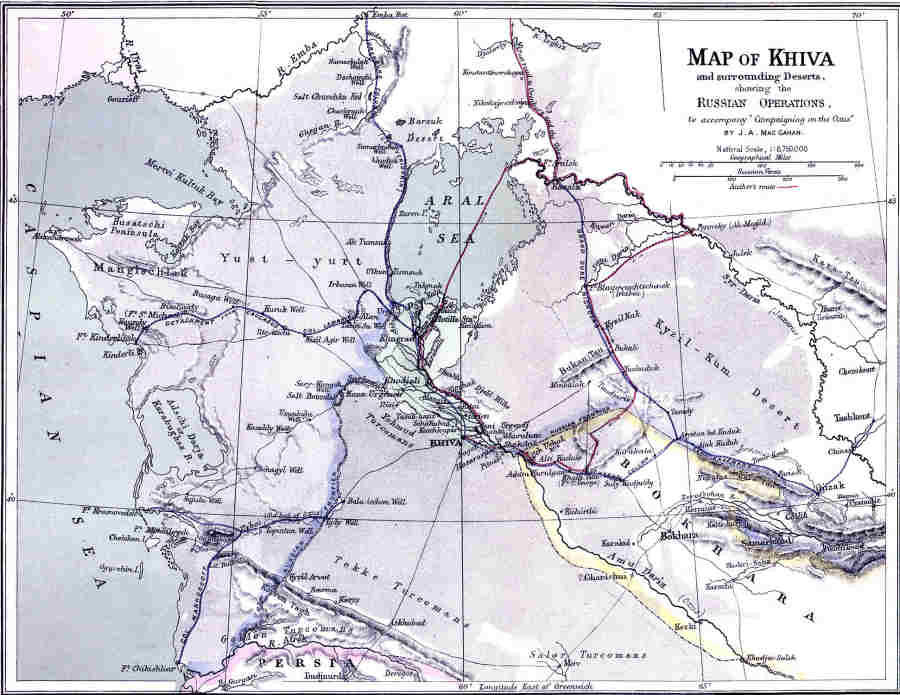

In February 1873, a combined force of 13,000 men under the command of General Kaufmann set out from five different locations: Emba, Mangishlaq, Krasnovodsk,

Chikishlar and Tashkent, each group aiming to converge and rendezvous in Khiva in several months time. Kaufmann accompanied the primary column, leaving

from Tashkent. The mission had been planned in minute detail using the latest intelligence reports and with supply depots provisioned at each prearranged

stopping point. Even so each column encountered numerous difficult problems, including the uncertain geography, heat, sunstroke, polluted water wells,

severe water shortages, snowstorms, sandstorms, Turkmen raids, and the exhaustion and loss of many horses and camels. The force that had been formed from

the combined columns from Krasnovodsk and Chikishlar found the going so bad that they were forced to abandon their equipment and return to Krasnovodsk.

|

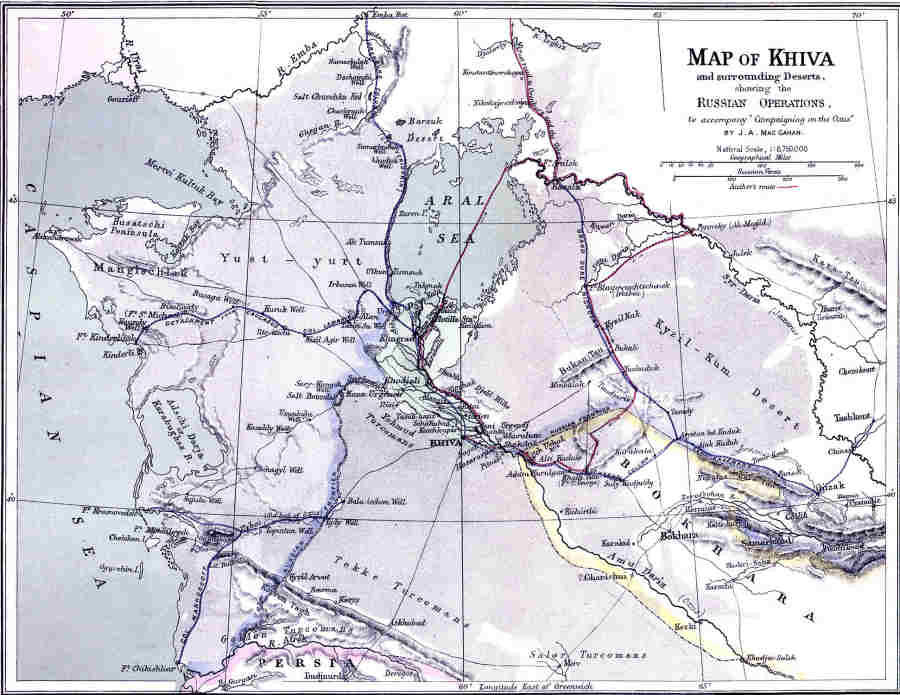

Map of the Russian operations, showing Kaufmann's route from Tashkent to Hazarasp.

From MacGahan's "Campaigning on the Oxus", published in 1874.

By a remarkable turn of events an adventurous American newspaper reporter from the New York Herald, Januarius MacGahan, had joined Kaufmann at his camp on

the Amu Darya and was allowed to accompany the Russian army as it marched on Khiva. Probably the very first Western war correspondent to report directly

from Central Asia, MacGahan had evaded Russian officers who had been sent to stop him and had then crossed the Qizil Qum alone to get an eyewitness

account of the fall of Khiva. He was given unprecedented freedom to follow events from the front, but like all "embedded" journalists he only saw events

from the perspective of his military hosts. Nevertheless thanks to him we have been left a detailed and highly readable report of the campaign.

First signs of water after crossing the desert. The water turned out to be a lake and not the Amu Darya.

From a sketch by N. N. Karazin, published in the Illustrated London News, 13 December 1873.

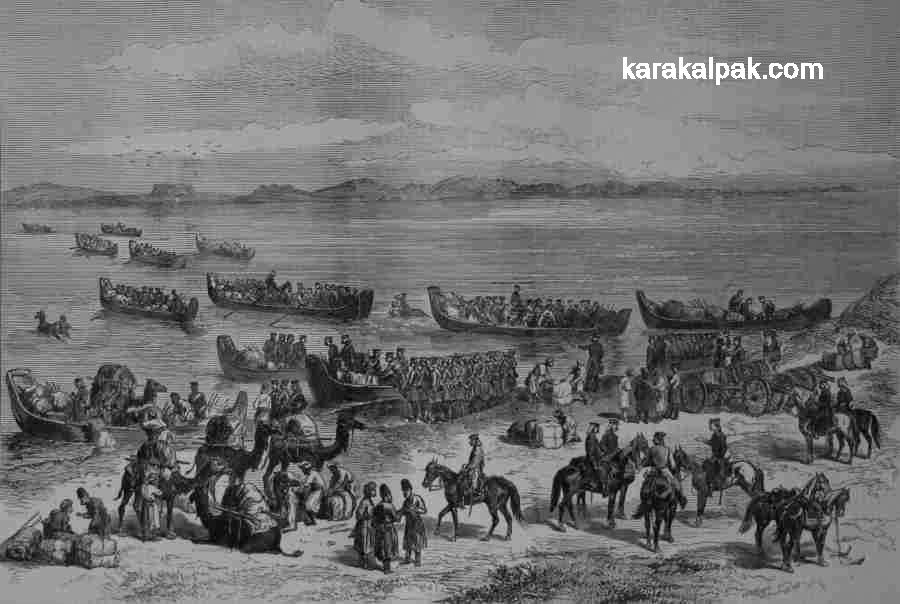

General Kaufmann's divisions crossing the Amu Darya at Sheikh-Aryk between 18-22 May 1873.

From a sketch by N. N. Karazin, published in the Illustrated London News, 22 November 1873.

Kaufmann finally crossed the Amu Darya near Hazarasp on 1 June, setting foot for the first time on Khorezmian soil. As he set out to march on the

citadel he was met by ambassadors of the local governor, who was an uncle of the Khan, offering the surrender and submission of the town. The Russians

therefore entered the citadel without firing a shot. They found that Hazarasp was a rectangular mud-built town surrounded by buttressed battlemented

walls and an outer moat, said by MacGahan to look a little like Windsor Castle from a distance! It was entered via a causeway crossing the moat and a

massive arched gateway with flanking towers. For troops who had just crossed the Qizil Qum, the region around Hazarasp was like a Garden of Eden, with

fields of waving grain, the fragrant blossom of mulberry, apple, apricot and cherry trees, tall young poplars and huge ancient elms providing dappled

shade, and with many little ponds and streams of water running in every direction. Peeping out from between the trees were the traditional Uzbek

farmsteads, built like little fortresses with buttressed outer walls strengthened with heavy corner towers, and arched and covered gateways.

While Kaufmann was approaching Hazarasp, General Verevkin, the head of the expedition from Emba, had completed a tough march down the barren west

coast of the Aral Sea and had finally reached the lush meadows and pastures of the northern delta. As he was preparing for his march on Qon'ırat the

following day, he received an extraordinary message from the governor, saying that he would refuse to fight unless the Russians were prepared to wait for

three more days by which time his canons would have arrived! Needless to say, Verevkin pushed on regardless and entered the town unopposed. Qon'ırat

was depopulated and in a terrible state of decay and desolation as a result of the continuing conflict with Khiva. The Aral Flotilla had already arrived

several weeks before and had already shelled Aq Qala and reconnoitred the lower reaches of the Amu Darya. As the Emba column left Qon'ırat, the

Mangishlaq column was just a couple of days behind them. Now the Russians began to encounter attacks by bands of local Turkmen and, at Xojeli, a

defensive force had to be dispersed by rockets. But it was only when the Russian column reached Man'g'ıt on 28 May that they were attacked by

the Khan's forces in numbers. The Khivans suffered heavy losses in this day of battle and thereafter their resistance deteriorated into hit and run

guerrilla warfare. On 4 June General Verevkin received a message from Muhammad Rahim Khan, begging an armistice and welcoming them as guests,

which he interpreted as a delaying tactic and consequently ignored.

Fearing that General Kaufmann was still some distance from Khiva, Verevkin decided he could not delay and set out on 9 June through the network

of surrounding gardens and farmsteads to reconnoitre the city of Khiva, only to stumble upon its outer walls by accident. Suddenly finding themselves

under fire from the city's defenders, the Russians were pinned down and General Verevkin was almost fatally injured. Unable to retreat, they held

their positions until their German-manufactured artillery could be brought into place to commence the bombardment of the city. The Khan sent out several

requests for a ceasefire, the last one saying that he had no control over his Turkmen troops which, though perfectly correct, was not a credible surrender

for the besieging Russian forces. The latter reluctantly ceased fire at sunset after they received orders to stop the bombardment from Kaufmann, who was

now only ten miles distant.

|

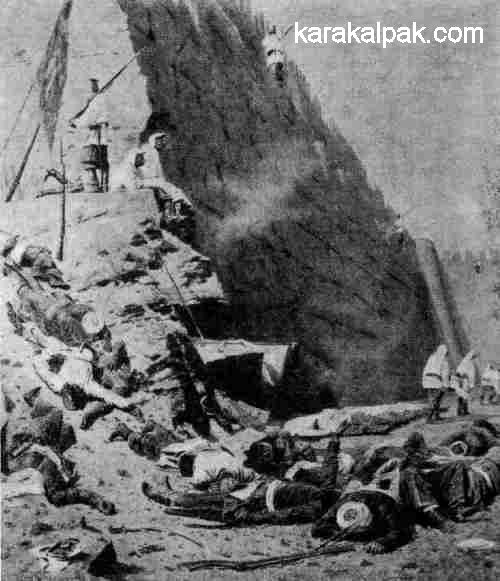

"Let them enter!" Russian troops in the process of capturing Khiva.

The painting by Vasiliy Vereshchagin attributed to 1871 but clearly painted at some time after June 1873.

An associated painting by Vereshchagin showing the aftermath of the bloody battle.

The next day General Kaufmann marched towards Khiva, but before reaching the city he was met by the Khan's uncle, the governor of Hazarasp, who had come

to surrender. The Khan had fled to Izmukshir after the belligerent Turkmen defenders had ignored his ceasefire instructions and the artillery barrage

had been maintained. Kaufmann continued his advance, meeting up with some of Verevkin's forces before victoriously entering the eastern Hazarasp gate

of the city. Meanwhile Verevkin's units, who were led by young gung-ho officers such as Colonel Skobelev and Count Shuvalov, were making the most of

overwhelming the final Turkmen resistance inside the northern gate.

"Mortally Wounded", another painting by Vasiliy Vereshchagin showing an injured Russian officer at Khiva.

According to MacGahan, everyone was disappointed by their first glimpse of the mundane inner city, with its cemetery, open spaces and trees, with a narrow

winding street lined with mud walls and mud houses, occupied by bearded men in dirty ragged khalats. However, once they entered the inner

citadel of the Ichan qala, they assembled in the great square in front of the Khan's rambling palace, the Kunya Ark, with its entrance gate flanked by

jade and white tiled towers glittering in the sun. Just to the left was the magnificently decorated Kalta Minar with brilliantly coloured bands of blue,

brown, and green including an upper band of Kufic script; in the distance the majestically elegant tapering minaret of the Juma Mosque; and to the rear,

the tiled but unfinished medresseh named after the current Khan. Kaufmann and his officers entered the Ark and assembled on the huge ayvan, used

as the Khan's audience hall, where they received refreshments from one of the Khan's ministers as the Russian band struck up "La Belle Hélène".

It must have been an extraordinary sight.

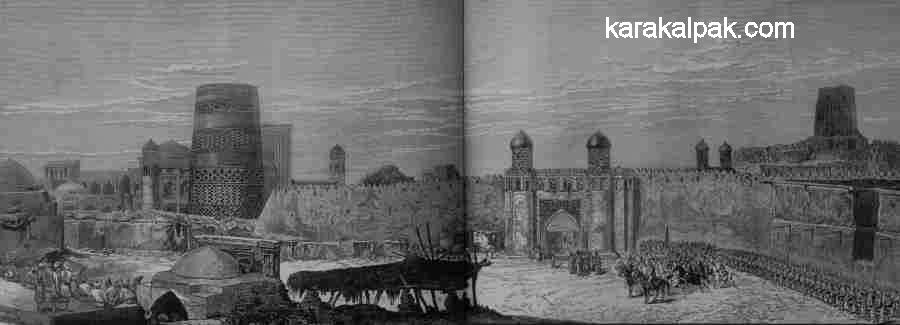

|

|

"The Celebration of Victory", an engraving from a sketch of Vasiliy Vereshchagin in Khiva.

Published in the Illustrated London News, 23 August 1873.

On 14 June the Khan returned to Khiva with his close followers and surrendered to Kaufmann, the huge figure of the young Khan kneeling in front of

the General who was only half his size. The Khan proposed that he should become a subject of the Tsar, but was told that the Tsar did not want to depose

him from the throne and was willing to show forgiveness subject to certain conditions. Work began immediately on composing a treaty between Russia and

Khiva.

Januarius MacGahan left us a great deal of detailed information on Khiva and Khorezm. It is clear that while Khiva had 300 shops, the main commercial

centre of the Khanate was at nearby Yani Urgench. Even at the time of the Russian invasion the wholesale merchants were importing a significant volume

of goods from Russia and Persia and the bazaars were selling Russian cloth and even chintz and muslin from England and Scotland.

From his writing one suspects that his initial feeling of disappointment on entering the city never disappeared:

"The exterior view of Khiva, from certain points, is striking and peculiar. High walls, with battlements and towers; a covered gate, with its heavy

towers of defence; the domes of the mosques and minarets, rising above the walls of the town; these things seen against the western sky in the light of

the setting sun, are very beautiful and picturesque; but the agreeable impression made by its exterior disappears on entering the town itself. There are

only three or four buildings in the whole place that make any attempt at architectural display; the rest are all of clay, and present but a miserable

appearance."

Yet at the same time he must have felt a sense of the magic of this remote and alien city that can still be experienced by the modern visitor today:

"It was now near midnight, and the silent, sleeping city lay bathed in a flood of glorious moonlight. The place was transformed. The flat mud roofs had

turned to marble; the tall, slender minarets rose dim and indistinct, like spectre sentinels watching over the city. Here and there little courts and

gardens lay buried in deepest shadow, from which arose the dark masses of the mighty elms and the still and ghostly forms of the slender poplars. Far

away, the exterior walls of the city, with battlements and towers, which in the misty moonlight looked as high as the sky and as distant as the horizon.

It was no longer a real city, but a leaf torn from the enchanted pages of the Arabian nights."

MacGahan had obtained his permission to travel into Central Asia with the help of Eugene Schuyler, the US Charge d'Affaires in Saint Petersburg. By

coincidence Schuyler was planning a trip to the Tien Shan, via the lower Syr Darya and Khokand, so the two set off on the first part of their epic

journeys together, sharing a railway carriage from Saint Petersburg to the Volga and then travelling by horse and carriage to Fort Number 1 at Kazalinsk

to avoid being intercepted by Russian security guards. Their carriage route passed along the northern shores of the Aral Sea, and Eugene Schuyler

recorded his observations of the Aral in his detailed travel diary:

"One day, near the station of Ak-julpas, for about three hours before sunset our road lay along the smooth beach of a bay of the Aral Sea. Far out in

the west we looked over an expanse of shallow water rippled by the wind, and forming pools on the flat sandy beach. In the distance was a low dark blue

promontory, and faint blue coast-lines, and to the east and south the desert rising and falling in low hillocks, covered with low leafless shrubs, the

coloured stems of which gave an aspect of purple, rose and yellow, mingling with the yellow-brown of the sand. But the charm lay in the sky, light blue

with fleecy clouds, and a sun which lighted up the clear, very clear, shallow pools of water and shore and sea with silver and pearly hues. White gulls

soared and dipped into the bay, hovering over our heads; while further away the water was covered with flocks of ducks and other water-fowl ..."

"The appearance of this shallow bay of Sary-Tchaganak is an example of the whole of this vast inland sea, a veritable waste of waters, 270 miles long by

160 broad. The surroundings are utterly desolate and uninhabited everywhere sandy hills and stretches of desert. Except birds, there are very few

signs of life ... The sea is shallow ... On the east and south one can walk for miles through the shallow water, and during the time of strong winds

the bed is for a long distance almost dry. Owing to the absence of good harbours, and the difficulties of getting into and out of the mouths of the Syr

Darya and the Oxus, the sea is almost unnavigable."

According to MacGahan, there were 22,000 Turkmen kibitkas, or households, in the region of Khiva at that time, of which half belonged to the

Yomut tribe, the rest belonging to Chodor (3,500), Imreli (2,500), Karadashli (2,000), Kara Jigeldi and Ali-Eli Goklen (1,500 each). This was

equivalent to a local population of 110,000 people, allowing for five members per family. During the treaty negotiations, the Khan had told Kaufmann that

he could not be responsible for the payment of the Turkmen share of the war indemnity, since even in peacetime they refused to pay any taxes. Kaufmann

decided he would collect the war indemnity from them directly, although this may have been a scheme to subdue the troublesome Turkmen tribes, since he

must have known they had no way of paying the sum that he set. He issued a proclamation ordering the Yomut to pay 300,000 roubles, equivalent today to

nearly $5 million, or almost $100 for every man, woman and child, with a deadline of two weeks. Before waiting for the deadline to expire he began

preparing to attack the Yomut encampments, much to the dismay of some of his officers, and then seized and imprisoned a dozen Yomuts who had come to

negotiate with him.

On 19 July, five weeks after the surrender of Khiva, a heavily armed column of Russian troops under the command of General Golovatchov headed off

towards the Hasavat canal, which supplied water to the Yomut settlement. MacGahan accompanied the Russian forces, having been encouraged to stay on by

the young Russian officer, Colonel Skobelev, who had struck up a close friendship with him. Finding the settlement abandoned the Cossack cavalry were

ordered to set fire to the Yomuts thatched mud huts, yurts and stacks of wheat and straw. After some time the Russian advance guard caught up with the

retreating Yomuts, men, women, and children, with their livestock and carts carrying all their worldly possessions. Eventually the Russian commander gave

the order to attack and the Cossack cavalry charged into the crowds, guns blazing and sabres flashing, while the infantry reinforced the attack with

rocket fire. Although attempts were made to spare the women and children, many were killed or injured during the massacre.

For the next few days the Russians continued through Izmukshir towards Il'jayli, incinerating anything that would burn throughout the Turkmen territories,

finally making camp in a region of Uzbek settlement. It was here that a party of Yomuts on horseback surprised them with a counterattack, and although

only a few were killed on either side it reminded the Russians that the Yomut could be an effective foe. This observation was reinforced two days later

when the Russians set out early in the morning to engage the waiting Yomut, only to be surprised once again by a clever ambush. The Russian commander was

injured and for a moment MacGahan thought that they would be routed, but the Yomut only had sabres and agricultural scythes and the rifles of the

disciplined Russian infantry soon made mincemeat of them. The Yomut later admitted to the loss of 500 tribesmen compared to 40 dead and wounded Russians.

Over the next two days the Russians attempted to hunt down the fleeing Yomuts, who had set off again with their families and possessions in their

arbas. By the time MacGahan had caught up with the vanguard of the Russian force, the Yomuts had been overrun. Unable to cross the canal, the

Yomuts had released their horses and fled, leaving those without a saddle to be cut down by the Cossack sabres. Dead Yomut tribesmen lay all about,

covered in bloody sabre-cuts, while their mothers, wives, and children cowered under their arbas loaded with carpets, cooking utensils and

clothing.

The Russian commander decided that the Yomuts had been punished enough. The Russian troops pillaged the carts, taking the best carpets, silk, and

jewellery and then set fire to the remains including the hundreds of arbas. The Yomut livestock was rounded up and herded back to Khiva. The

Yomut's livelihood had been completely destroyed.

General Kaufmann, who had come with reinforcements from Khiva, now set up camp at Il'jayli and issued a proclamation to the remaining Turkmen tribes,

demanding an enormous indemnity, equivalent today to over $400 per kibitka, to be paid within 14 days. The Turkmen attempted to pay in kind,

with horses, camels, carpets and a large amount of silver jewellery, with the Russian officers keen to acquire a genuine Turcoman horse and the large red

and white Turkmen main carpets selling for the equivalent of over $500. However, at the end of the deadline the Turkmen had only paid half of the total

indemnity. Realising their difficulty in raising the full sum, Kaufmann gave them another year to fulfil their obligations.

Russian Khorezm

Within weeks of the fall of Khiva, General Kaufmann had sent a draft of his proposed treaty with the Khan to Saint Petersburg for approval. The approved

copy was returned to Khiva and an Uzbek translation was prepared for the Khan. It was signed on 23 August 1873 in the Khan's garden at Gendiamin.

The Khan was allowed to retain his position as the legal sovereign, but only as a "humble servant" of the Russian Emperor. In return the Russians would

have a right of residence in the Khanate, freedom to conduct trade unburdened by taxation, and an indemnity of 2.2 million roubles to be paid with

interest over about 20 years. Despite clear instructions that he should not annex the Khanate, Kaufmann pushed his luck and persuaded the Khan to cede

not only the left bank of the Syr Darya to Russia but all of his lands on the right bank of the Amu Darya as well. This would become the Amu Darya region

of the Syr Darya Province of Russian Turkestan, to be administered by a new Amu Darya Department. The Khan would control the whole of the left bank, up

to the foot of the Ustyurt and the region of the Uzboy as far as the Caspian Sea. However Russia would take the entire Ustyurt plateau and would control

the Caspian coast. When news of the treaty reached London there was a hostile reaction by the British who realised they had been duped by Saint

Petersburg. Right-bank Khorezm had become the latest colonial territory to be added to the growing Russian Empire.

The Russians now turned towards the defence and administration of their new Amu Darya Otdel or Department, within the larger Syr Darya

Oblast ruled from Tashkent. At the time of its annexation its two main towns were thought to be Shoraxan, close to the Amu Darya and just

south of modern To'rtku'l, and Shımbay. General Ivanov was installed as the first Commandant of the new territory, responsible for exercising

military control over Khivan affairs on behalf of General Kaufmann. The first Russian fort was erected in the garden of the Khan's Vizier close to the

banks of the Amu Darya, 3km from Shoraxan and 10km from the Amu Darya ferry. It was named Fort Petro-Aleksandrovsk (close to modern To'rtku'l). During

that winter a second site was identified for the erection of another garrison close to the village of No'kis, strategically situated at the beginning of

the Aral delta, with one of the best river crossings and at the start of the road to Kazalinsk. General Ivanov initially decided to garrison the bulk of

his troops at No'kis and work began on the construction of the fort during the summer of 1874. Unfortunately the location turned out to be less than

satisfactory, with the site subject to flooding and with no clay available for brick-making. Ivanov therefore decided to limit the size of Fort No'kis

to 350 men and to site his main garrison at Petro-Aleksandrovsk, which would now become the main administrative headquarters for the Amu Darya Division.

The Russian fort was located to one side of a large open square and was surrounded by a wall with an imposing gateway. Gradually a European-style town

grew up around the square and by 1885 it had a general shop, a small hospital, a public baths, and houses for the governor and families of the senior

officers. Over the next few years a permanent dock was built at No'kis for the Aral Flotilla, which now had 550 sailors, about half a dozen paddle-wheel

steamers, and a dozen heavy barges for transporting troops.

The Russian takeover of Khiva suddenly opened up Khorezm to Europe and the West, although foreigners were not allowed to visit Turkestan without special

permission. Now the Russian paddle steamer "Perovsky" could ferry passengers from Kazalinsk to No'kis across the Aral Sea, making it possible to reach

Khiva from Orenburg by carriage and boat without the perilous crossing of the Ustyurt. Russian surveyors, economists and geographers flooded into the

region to compile their various reports, and travellers and adventurers soon followed behind them. Between 1874 and 1880 some five separate expeditions

came to map, chart and survey the lower Amu Darya. Thanks to the Russian photographer Krivtzov we even have a photographic archive of the Ichan qala and

the surrounding residential area of Khiva as early as 1873, showing it to be a rather scruffier and run-down version of what we see today, apart from the

later additions such as the Islam Khoja ensemble. In reality it was probably always like this the modern Ichan qala tourist site is a much-

restored, depopulated and sanitised Walt Disney version of the original city, though still fascinating nevertheless. Another Russian visitor to Khiva

at this time was A. L. Kun from Saint Petersburg, who relieved the Khan of more than 1,500 manuscripts, including the history of the Khanate written by

Munis, taking them back to the Russian capital for study.

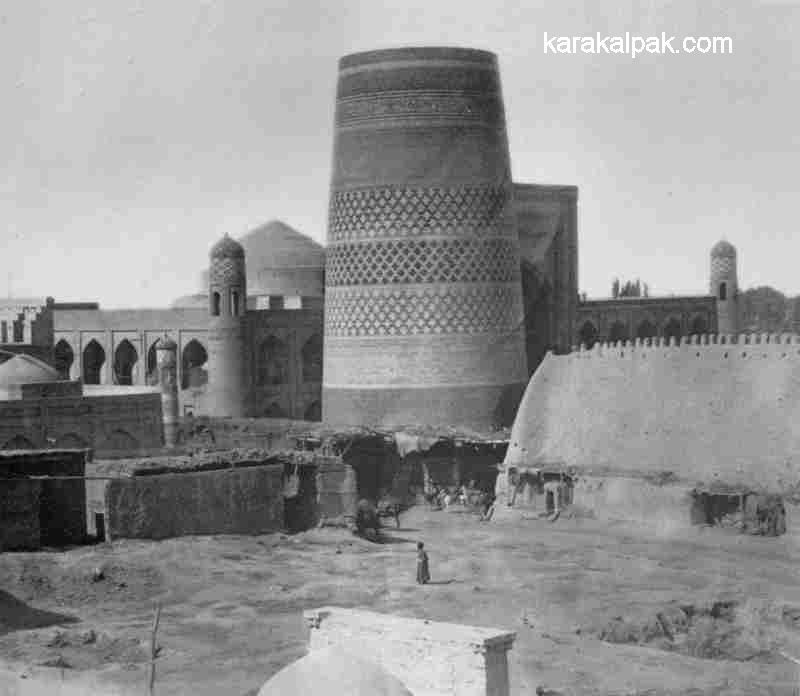

View of Khiva, showing the Kalta Minor, Muhammad Amin Khan Medresseh and the Kunya Ark.

Photographed by Grigoriy Krivtzov in 1873.

Just as important was the information that was gathered in rural Khorezm showing the state of the ordinary people. Quite remarkably the Russians invited

an English military river and irrigation specialist from the Royal Engineers to Khorezm shortly after the annexation. Major Henry Wood has given us an

interesting picture of life in the lower Amu Darya and delta in 1874, albeit somewhat preoccupied with water. Wood visited Khorezm in the summertime

after a 15-hour cruise down the eastern side of the Aral Sea from the headquarters of the Aral Flotilla at Kazalinsk. He was moved by his first sight of

this waveless green expanse of sea, surrounded by swamp and desert and devoid of other ships or ports. Entering the central arm of the Amu Darya, the

banks were lined with tall rushes, behind which lay impenetrable scrubby and thorny tugay jungle. The latter was the home of the tugay

tiger, a natural predator of the wild deer and boar which thrived in this remote wilderness. The central region of the delta was still wild with

weed-choked lakes filled with coloured water lilies and stands of reeds almost as tall as trees "... adding immensely to the sense of solitude and mystery

which pervades these uncommon scenes". In the flood season the whole area from Xojeli to Qon'ırat became one huge lake. The mosquitoes were so

dreadful and "exquisitely painful" that even the hardy Russian soldiers had been issued with protective nets!

|

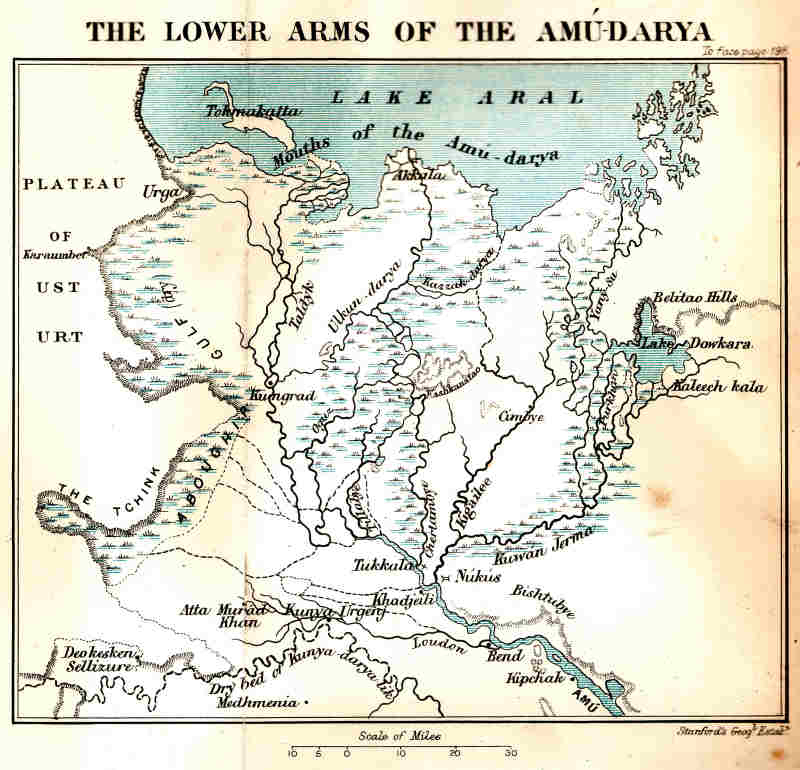

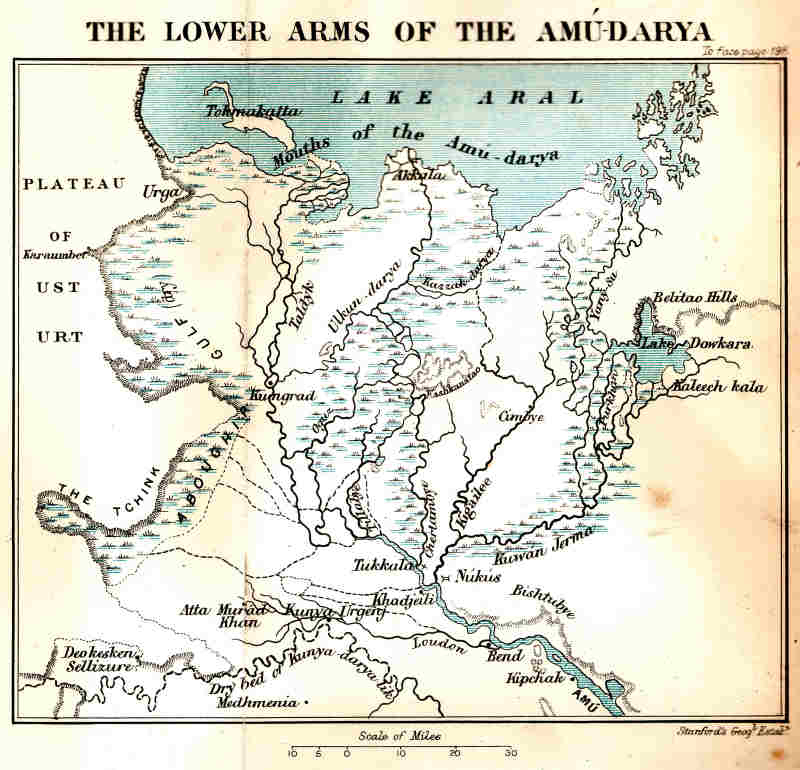

A map of the Amu Darya delta in 1873.

From Henry Wood, The Shores of Lake Aral, London, 1876.

This central delta area was occupied by the Karakalpaks, described by Wood as the poor underdogs of the region, despised by both their Uzbek and Turkmen

neighbours. Their material situation had changed very much for the worse over the last 18 years. During the 1858 rebellion the Yomut Turkmen who

cultivated land in the Aybugir Gulf had rebelled alongside the Karakalpaks. The Khan of Khiva, Sayyid Muhammad Khan, decided to kill two birds with one

stone and dammed the Laudon canal, depriving the Turkmen of water and flooding the Karakalpaks. Unfortunately every summer since the excess water had

turned the important Karakalpak pastures into swamps at just the time they were needed for cattle-grazing. The population of Qon'ırat had

consequently shrunk from 6,000 to 2,000 since the 1850s and even the population of Shımbay, the second town in the delta, was a mere 1,200,

although Wood reported the total Karakalpak population to then be 50,000, probably an underestimate. Qon'ırat was the main agricultural area,

with small patches of cereals, melons or lucerne and with the wetter areas used for rice farming, with the local Karakalpak urchins guarding the crops

from flocks of wildfowl. On the left bank of the river at Qon'ırat, areas of pastureland alternated with patches of low thick jungle.

Shımbay had fields of maize and lucerne with fruit orchards and irrigation channels lined with poplar trees. However that summer the whole

region was plagued by vast swarms of locusts. Many Karakalpaks were fishermen, living on floating islands of vegetation and using fixed nets to catch

large coarse sturgeon, which they dried and salted for sale.

|

Karakalpak yurts and qayıqs at the mouth of the Ul'ken Darya,

with the gunboat "Samarkand" moored in the distance. Sketched by Nikolay Karazin in 1873.

The region around Khiva was much more prosperous with thousands of fortified farmhouses, or ha'wli, occupied by the wealthier feudal landowners.

The range of crops grown in this region was much wider, with good quality cotton, wheat, maize, lucerne, sesame, hemp, and madder as well as tobacco and

opium, the latter two crops highly taxed. Tree cultivation was also widespread around Khiva, not just for fruit but also for timber. There were some

fortified ha'wli in the vicinity of Shımbay, but none further into the delta. No'kis was then just a mud-walled village a mile or so from

the new Russian fort and was situated in a flat region of thick tamarisk and eleagnus jungle.

Sadly Wood does not describe the towns of Khorezm, but we do get a brief picture of some of them from Captain Burnaby who visited the region two years

later and wrote a book that is somewhat short on detail. He found New Urgench surrounded by high walls in a very bad state of repair, many having

crumbled into the outer ditch. Nevertheless the town was a major centre of trade, with the roads blocked by hundreds of carts delivering corn and

"various kinds of grass" to the market. Burnaby witnessed a caravan of camels one mile long, bringing in goods from other parts of the Khanate. The

busy bazaar occupied a street that was covered with rafters and straw to provide shade from the sun. The surrounding countryside was occupied with square-built houses

with gardens enclosed by high walls. As Burnaby approached Khiva he could see "richly-painted minarets and high domes of coloured tiles" towering above

the leafy groves and orchards that surrounded the town.

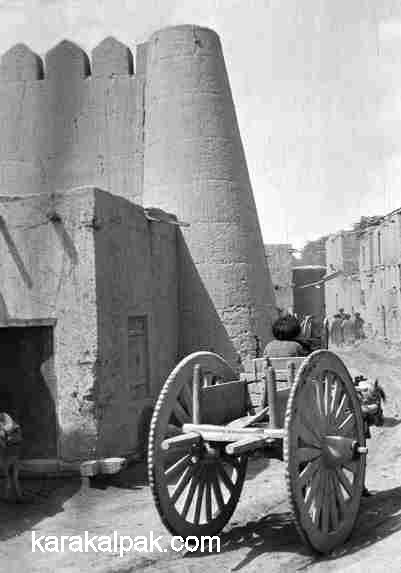

"We now entered the city, which is of an oblong form, and surrounded by two walls; the outer one is about fifty feet high; its basement is constructed

of baked bricks, the upper part being built of dried clay. This forms the first line of defence, and completely encircles the town, which is about a

quarter of a mile within the wall. Four high wooden gates, clamped with iron, barred the approach from the north, south, east and west, whilst the walls

themselves were in many places out of repair."

"The town itself is surrounded by a second wall, not so high as the one just described, and with a dry ditch, which is now half filled with ruined

debris. The slope, which leads from the wall to the trench, had been used as a cemetery, and hundreds of sepulchres and tombs were scattered along some

undulating ground just without the city. The space between the first and second walls is used as a market place, where cattle, horses, sheep and camels

are sold and where a number of carts were standing filled with corn and grass."

Burnaby had reached the bazaar square, opposite the Hazarasp gate. This had been one of the traditional places for execution within the city:

"Here an ominous-looking cross-beam had been erected, towering high above the heads of the people with its bare gaunt poles."

"This was the gallows on which all the people convicted of theft are executed; murderers being put to death in a different manner, having their throats

cut from ear to ear in the same way that sheep are killed."

Execution by cutting the throat also took place in a deep square pit close to the Khan's palace, while hangings also took place on the north side of the

citadel, by the slave market, where there was also a stake for impalement. Cruelty lay at the very heart of the Khanate's regime. Burnaby passed on

into the inner citadel:

"... The streets are broad and clean, whilst the houses belonging to the richer inhabitants are built of highly polished bricks and coloured tiles, which

lend a cheerful aspect to the otherwise somewhat sombre colour of the surroundings. There are nine schools; the largest, which contains 130 pupils, was

built by the father of the present Khan. These buildings are all constructed with high, coloured domes, and are all ornamented with frescoes and

arabesque work. The bright aspect of the cupolas first attract a stranger's attention on his nearing the city."

The conditions of the ordinary people in the countryside were dreadful at this time. Excluding the feudal lords, most people lived in yurts, grouped

into small villages of tens or hundreds of dwellings. The peasants were not only abjectly poor but were at constant risk of attack from bands of

ravaging Turkmen, especially in the winter when the frozen rivers and lakes made access easier. With only two battalions under his command, General

Ivanov simply lacked the resources to protect the newly annexed right bank territories from these Turkmen incursions. We know he wrote several letters

to the Khan insisting on restitution following Chodor thefts from the Karakalpak. The artist Nikolay Nikolayevich Karazin returned to Khorezm to paint

in the summer of 1884, but discovered that many Karakalpaks were living in squalid conditions. Reeking of rotten fish, their yurts lacked any carpets

or felts and contained little more than an iron trivet and cauldron with a few reed mats on the floor. Most of the awıls, or small

villages, were equally impoverished and Karazin did not see a single healthy person during his visit even the livestock looked sickly. Karazin left

a picturesque description of the stifling heat, the myriad of mosquitoes, the vast plagues of locusts, the rivers teaming with fish and the lakes and

marshes alive with pelicans, swans and flocks of small birds.

"A Karakalpak of Asiatic Origin". Published in the Illustrated London News, Special War Number, 23 May 1877.

The local Karakalpaks regarded the Russian invaders, or "white shirts", as friends of the devil. The Aral Flotilla paddle steamers were called "devil

boats" because they constantly cut the fishing nets of the local fishermen who lived in riverside dwellings built on artificial reed platforms. They

sought revenge by repositioning the navigation markers, trying to trick the boats into side channels where they would run aground. For protection

during the bitter delta winter the Karakalpaks moved their yurts from their summer grounds into huge mud-walled enclosures, located in many places

including Qon'ırat, Shımbay, No'kis, Bozataw, and the Aral Sea coast. Karazin estimated the Shımbay enclosure had a diameter of 1½

kilometres, contained 40,000 yurts and even had its own covered bazaar.

Poor Karakalpak barge haulers or qayıqshi on the Amu Darya.

Sketched by Nikolay Karazin, who described them as "semi-barbarian paupers".

However, not every yurt-dweller lived in abject poverty. A. Kaulbars, who arrived with Kaufmann in 1873, visited a decorated yurt with carpets and bags

hung from the inside walls, some filled with provisions, several iron cooking pots, millstones and weapons. But he also observed poor men who could not

even afford to live in a yurt, especially the Karakalpaks in the northern delta who were forced to live in tents or dugouts.

Henry Lansdell reported that by 1885 the condition of the nomads in the southern portion of the Amu Darya Province around Shoraxan was slowly improving.

Because the nomads were vulnerable to Turkmen raiding parties from the left bank, they had had to remain inland close to wells far from the river, and

could not take their cattle to the best pastures along the banks of the Amu Darya during the spring and autumn. To help the nomads develop their herds,

the Russian governor had established a military post at Uch Uchak, close to the Bukharan frontier, to defend the surrounding riverbanks and regions of

tugai forest.

Of course Russia's expansion into Central Asia did not stop with Khorezm. Despite the punitive action against the Yomuts during Kaufmann's campaign,

raids by Turkmen nomads began immediately after the Russian forces departed from Khiva, partly in an attempt to recoup their losses. Since the Khan had

been left in control of left bank Khorezm without any military forces, he was powerless to control the Turkmen minority who could only be restrained by

direct intervention by General Ivanov's garrison at Petro-Aleksandrovsk. This led to repeated requests from Ivanov for the complete annexation of Khiva,

a request continually rejected by Saint Petersburg. However, when it came to the Turkmen tribes to the south and east of Khorezm, Tsar Aleksandr II was

left with little alternative than to allow his officers in the field to take an increasingly aggressive stance. As early as 1877 the Russians had

attacked the fort of Qizil Arvat, but the Russo-Turkish War intervened and momentum was lost. In 1879 another Russian expeditionary army advanced from

Chikishlar and attacked the Tekke at their Geok-Tepe fort in the Akhal oasis. After an artillery barrage the Russians tried to storm the fort but the

Tekke fought like devils, killing and wounding 450 attackers and forcing them to retreat back to the Caspian.

The defeat embarrassed the Russians, who resolved to crush Turkmen resistance. At the beginning of 1880 Tsar Aleksandr summoned Mikhail Skobelev to a

meeting in Saint Petersburg and instructed him to conquer the Akhal Tekke once and for all. Skobelev, now known as the "White General", had become a

distinguished soldier following his exploits at Khiva and had gained a formidable reputation. Skobelev realised that transport and artillery would be

the key to success and immediately formed a railway battalion who began to build a railway line from the Caspian port to Qizil Arvat. Realising that

yurts were relatively undamaged by normal artillery shells he ordered special ammunition that had been charged with petroleum. At the end of the year,

his expeditionary army reached and surrounded the stronghold of Geok-Tepe. After a siege and numerous violent skirmishes, Skobelev's sappers finally

managed to mine the ramparts and in the early morning of 24 January 1881 a stretch of the mud-brick fortification was blown to dust. In the bloody

hand-to-hand fighting that followed some 4,000 Turkmen were massacred and many thousands more were hacked to death by the flying columns who pursued the

escaping fugitives. The cost to the Russians was 300 lives. News of the defeat was received with uproar in London and with dismay by the other Turkmen

tribes and the old regime in Khiva, who still hoped beyond hope that their independence might one day be restored. The Russian advance looked

unstoppable. Skobelev was unapologetic for the massacre and later commented, "... in Asia the duration of the peace is in direct proportion to the

slaughter you inflict upon the enemy. The harder you hit them, the longer they will be quiet after."

Within a few years the Russians had negotiated the submission of the Turkmen tribes in the Merv oasis, completing the conquest of Turkmenia. The

Transcaspian Oblast soon became the fifth and final province of Russian Turkestan. The annexation of Merv caused enormous concern in Britain

over Russian ambitions for Iran and India, which were only heightened when local Russian military leaders captured the Afghan frontier region of Pandjeh,

following Russian reassurances that their advance into Asia was complete. A Russo-British war looked imminent for a while, but fortunately diplomacy won

the day and an Afghan Boundary Commission was convened in 1887 to establish the dividing line between the Russian and British colonial territories.

The agreed borderline defined the Russian sphere of influence for almost a century until Russian tanks crossed the Amu Darya into Afghanistan in 1979.

The official Soviet histories are keen to emphasise the benefits that came with Russian control. However in reality Russian policy was one of

non-interference and Khorezm remained largely isolated and stuck in a time warp. Obviously there were external influences, but they were limited. When

Muhammad Rahim Khan attended Aleksandr III's coronation in Moscow he returned with cigarettes and a telephone and introduced the ladies of his harem to

corsets and bustles! One of the very first Russian schools to open was in Khiva in 1884, and was founded by a local official after returning from a visit

to Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Schools for boys and girls were opened in Petro-Aleksandrovsk along with a library in 1907, and more schools were

opened later in Shoraxan and Shımbay. However these were solely for the benefit of senior Russian officials and local members of the aristocracy.

The vast majority of the population remained illiterate, their only opportunity for a rudimentary education being through the local mullah in a

mekteb, or religious elementary school, where boys were taught to read the Qur'an. Tribal leaders who could afford it would try to send their

boys to medressehs in Khiva or even Bukhara. A hospital opened in Shabbaz (modern Biruniy) and first-aid posts in No'kis and Shımbay, although

for the ordinary population illnesses continued to go untreated and the death rate remained high. Roads were built including the "Russian Road" from

Petro-Aleksandrovsk to Shımbay via No'kis.

The sheer isolation of Central Asia from Europe demanded faster communications and General Kaufmann promoted the idea of a railway from Orenburg to

Tashkent. Despite the completion of a survey by 1879, showing that a line could be constructed across the Qara Qum, it was never built. As we have

already seen, the first railway was constructed for purely local military reasons from the harbour of Asunada, south of the port of Krasnovodsk on the

Caspian, to Qizil Arvat in Turkmenistan in 1881 by General Skobelev. It was finally decided to extend this line to Ashgabat in 1884-85 but the

Anglo-Russian dispute over Pandjeh in 1885 made the construction of a Tashkent railway a strategic priority and by the end of 1886 the railway line had

already reached the bank of the Amu Darya opposite Charjou. Work began on continuing the line northwards with the construction of a wooden bridge over

the Amu Darya the following year, the railway reaching Samarkand in 1888 and eventually Tashkent in 1898 a massive investment and an incredible

achievement. Colonel Le Messurier, a military officer from England, travelled the line in the autumn of 1887. At that time the railway was entirely

under Russian military control and already had approximately fifty engines and a large amount of rolling stock. Although essentially a tourist, le

Messurier recorded the details of the railway like a military observer, and noted that the whole 665 miles from Asunada to Charjou could be traversed in

53½ hours, including stops. On reaching the Amu Darya, le Messurier was told that the wooden bridge would be finished in January, in another three