|

Contents

Class Structure

Family Life

Marriage and Divorce

Housing

Work and Unemployment

Income and Consumption

Clothing

Food and Diet

Officialdom

Transport

Education

Healthcare

Welfare

Old Age and Death

Conclusions

Postscript

Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms

References

Class Structure

We have been unable to find any official statistics on the distribution of income or wealth among the

Karakalpak people per se. Figures for Uzbekistan as a whole highlight the deterioration of income

distribution since 1991, which mainly occurred during the first five years of economic transition:

Change in the Distribution of Money Wages 1991 to 2001.

| Income Quintile | 1991 | 2001 |

| Top 20% | 11.2 | 6.1 |

| Second 20% | 11.8 | 9.2 |

| Third 20% | 15.7 | 13.8 |

| Fourth 20% | 22.7 | 22.3 |

| Bottom 20% | 38.6 | 48.7 |

| Ratio of bottom to top quintile | 3.4 | 8.0 |

Source: State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

The Karakalpaks have probably suffered worse than most. This is not only because there are far fewer well-paid

jobs in Karakalpakstan compared to the rest of the country, which has the benefit of the major economic centres

(Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara), but because the largest Karakalpak employment sector is in agriculture.

Although wages in finance, industry, construction, transport, communications, and management have risen over this

period relative to the average wage, those in agriculture have more than halved.

The World Bank noted in 2003 that although the average agricultural wage had been comparable to that in industry

in 1991, by 2002 it was only 21%. This was not due to a realignment of wages to productivity since productivity

growth in agriculture was higher than that in industry.

A 1999 survey of Karakalpaks from the relatively wealthy area of To'rtku'l, and the two poorer regions of Taxta Ko'pir

and Moynaq, identified six categories of social stratification and defined them as follows:

- the very rich or o'te baylar were people who were personally unknown to the respondents but were gossiped about,

such as TV soap stars, |

- the rich or bay were either business people, owners of significant amounts of land or cattle, senior managers

and important officials. They lived in a big house, |

- the well-to-do or qurg'ın could afford to pay for items beyond food, such as clothing, or a good education or

a wedding for their children, |

| - the middle-class or orta turg'ınlar did not have problems feeding their families, |

- the poor or jarlı were ordinary farm workers, the unemployed, or those who had lost the family bread-winner.

They are barely able to make ends meet and suffer from hunger, |

- the destitute or beggars or tilenshilar or qayır sorawshılar have already sold all their possessions and are

jobless and probably homeless. |

Participants were asked to categorize households in their own communities and concluded that most families were either

well-to-do (5-10%), middle class (20%), or poor (40-80%).

Obviously this sample is not statistically representative and excludes any contribution from a community in No'kis.

Nevertheless it does echo the type of distribution shown in the table of money wages.

The real value of this study, however, is that it provides an insight into the social changes that have taken place

among Karakalpaks since independence. It shows that the heavy bias towards the poor is a relatively recent phenomenon.

The participants in the survey unanimously noted that levels of poverty and destitution had increased over the previous

ten years. In the past the buying capacity of their earnings was higher, prices for food and other goods and services

were not high, medical services were better and basically free of charge, and there were enough jobs to go round.

Also in the past the majority of the population was regarded as middle-class and the rich and poor were proportionally

fewer in number.

Unemployment began to increase in the 1990s as former Soviet outlets for Karakalpak goods disappeared and subsidies

were eliminated. There were huge cutbacks in government jobs and in labour-intensive cotton farming. To make matters

worse agricultural output also declined as a result of widespread soil salinization. Price controls were relaxed and

food subsidies withdrawn so prices of everyday goods accelerated, outpacing wages, the payment of which became increasingly

delayed. The introduction of the som in 1994 was followed by colossal inflation - the initial som coupon

lost 90% of its value in six months and the som itself suffered from high inflation for most of the 1990s.

Wealthy and middle-class families saw their financial savings destroyed within a matter of years. Only those whose wealth

was tied up in assets remained unscathed.

Family Life

For Karakalpaks the family rates very highly on the traditional scale of values. Most Karakalpak families are large, although

not as large as they were in the past thanks to increased family planning over the last decade. Today the average household

size is currently 5.8, urban households being smaller at 5.6 and rural larger at 6.1. The main reason households are large

is because women have many children. The average number is about 3, although the rural poor have more while the urban

non-poor have less.

It is also partly because married couples often continue to live with their parents. Many young married couples cannot

afford a home of their own and therefore live in the home of the groom’s parents after the wedding. At the same time some

married couples care for their parents in their old age. For example, an eldest son may invite his mother to come and live

in his house following the death of his father.

Children are generally respectful and well-behaved. Street vandalism and graffiti are unheard of and crime is very low.

In many families the grandmother and the eldest child will help with the care of the young. Relatives usually live close by.

In small villages or awıls most of the men may still belong to the same clan.

Life revolves around the home and the extended family and friends. Families tend to eat together in the evenings and make

their own entertainment. Watching TV is the main recreation. Almost every home has a television set and many have a radio

(90% of homes in Uzbekistan have television and 40% have a radio). Most people can only receive the official terrestrial

Uzbek channels, as well as Kamalak TV from No'kis and To'rtku'l TV, which is broadcast in the south. Only a very small number

of wealthy families (less than 1% of households) have access to satellite TV or to the internet.

Social occasions involving joint family celebrations are limited to festivals or formal ceremonies, such as Nawrıs or the

circumcision of a boy. A wedding in a well-to-do family can be a huge and expensive affair with hundreds of invited guests,

most of whom will be offered accommodation with neighbours and friends.

Nawrıs celebrations on a cold spring day in No'kis.

Compared to other parts of the globe, it is not traditional for Karakalpaks to venture out for an evening of entertainment,

even in No'kis. There are restaurants and cafes in the capital, ranging from the top-end Sheraton Club run by Koreans, to the

lively Neo restaurant, and our favourite, the basic but friendly Mona Lisa, run by Armenians. Such places are mainly frequented

by officials, the sons and daughters of the wealthy, and foreign expatriates. There is a State Theatre named after Berdaq

and a State Youth Theatre named after Sapar Xojeniyazov, and both have occasional performances frequented by the No'kis intelligentsia.

Cinema-going is also unusual and many small regional cinemas have closed since independence.

Families are far more likely to go out to watch their children participate in a sports event such as volleyball or basketball

at one of the many local sports halls or outdoor sports grounds, especially in the warmer months. Local lakes and canals are

also frequented for swimming and relaxation, a family picnic, or a barbeque. A high proportion of Karakalpak men are fanatical

about fishing, which is not only an important recreation but can put food on the family table. A new recreational Aqua Park

was opened by President Karimov in 2005. For a special treat kids might be taken to the small funfair in the centre of No'kis.

Only a very small minority regularly attend a mosque. Religious worship in public was strongly discouraged during the Soviet

era, so people conducted their religious activities in private. Although a small number of mosques have been constructed with

official consent since 1991, the most prominent being the Cathedral Mosque in No'kis, the number of regular worshippers

remains proportionally small.

Marriage and Divorce

The marriage rate fell sharply after independence. For Uzbekistan as a whole there were 12.9 registered marriages per 1,000

of the population in 1991. This fell to 7.5 marriages in 1995 and since then the level has never recovered. The main reasons

are economic and cultural. The increased cost of living, coupled with the decline in incomes, means that many young couples are

discouraged from setting up home together. At the same time the traditional custom of demanding a bride price, or qalın',

from the groom’s family has recently been revived. Although not yet a universal practice, when it is demanded it can be set

at a high level, barely affordable by the groom’s parents. One response to this has been an increase in the number of

arranged kidnappings, either agreed by the bride or her family or both, thereby creating a pretext for a reduced qalın'

and avoiding the costs of a full-blown wedding.

Increasingly young people are left to choose their own marriage partners, although more traditional parents still choose a

bride or groom for their son or daughter. Although they are no longer obliged to obey, many young Karakalpaks are respectful

and obedient and most will follow their parents’ wishes.

An official wedding is a major event and an opportunity for the parents to demonstrate their generosity and status in the

community. Although the ceremony is based on both Islamic and Karakalpak traditions, prospective married couples aspire

towards Western-style dress with the bride wearing white chiffon and lace – if her parents can afford it – and the groom

wearing a suit and carnation. The legal marriage ceremony itself is a low-key affair but the marriage celebrations, which

include the unveiling of the bride, are quite the opposite and go on for the whole day.

Divorce is legally possible but remains low. The number of divorces is only one tenth of the number of marriages. Most

divorces occur among the under 30s.

Housing

Roughly one quarter of Karakalpaks live in concrete apartment blocks and three quarters live in single storey houses, known

as u'y, sometimes referred to as tams in the countryside.

Most apartment blocks have four or five storeys and are located in the main conurbations, especially in No'kis, but also in

Biruniy, Xojeli, Taqıyatas, and Qon'ırat, although some smaller blocks can be found in rural areas on former collective

farms. Many of these typical Soviet-style buildings were constructed between 1979 and 1990, although many look much older.

Some have a single noisy window-mounted Russian air conditioner but many do not and are like ovens in the summer. They are

more likely to have either steam or gas heating during the freezing winters. There was generally no provision for gardens

or recreational space and local children play on the barren patches of earth between the apartment blocks.

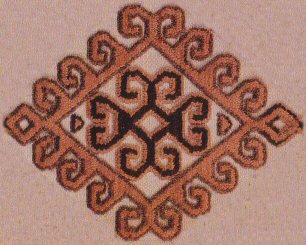

As a link with the past many apartment blocks have been decorated with paintings, murals, or mosaics of traditional Karakalpak

embroidery and carpet motifs, such as segiz mu'yiz or Xorasanı mu'yiz.

|

Soviet-style apartment block in No'kis.

U'ys and tams are to be found everywhere, both in the towns and in the country. Towns like To'rtku'l, Man'g'ıt,

Xalqabad, Shımbay, Shomanay, and Moynaq are all low-rise conurbations with street after street of single storey houses, as are

the suburbs of No'kis. In the rural areas 95% of people live in houses as opposed to apartments. Houses generally look more

prosperous in the south of Karakalpakstan than in the north.

Tams were traditionally built with mud-brick walls and a flat roof, the walls being plastered with a mixture of mud and

straw. The modern version looks very similar but is constructed with brick and cement rather than mud. Although the average house

does not have a large number of rooms, the rooms themselves tend to be large to accommodate the whole family. Traditions run deep

and most Karakalpak homes do not have a large amount of furniture, the latter having been introduced by the Russians. Most living

rooms have one or two cupboards and a low portable table. People sit on the floor on quilted mattresses, known as ko'rpe

leaning on cushions, just as in the past. Often a pile carpet is hung as a decoration on the wall. The living rooms are heated

during the winter with a large metal boiler and are shaded from the sun in summer by curtains or blinds.

|

Karakalpak tam in Xalqabad with homemade TV aerial.

Most tams have a garden or yard used for growing vegetables or for keeping a few chickens or animals. If not

the family might have a patch of land nearby. The 2002 Household Budget Survey showed that 74% of households in Uzbekistan

have access to land plots, 57% have a place for keeping cattle, and 36% have a hen house. Most rural gardens also contain a

tandır oven for baking the daily nan bread. The Tashkent government intends to ensure that every family

has a small plot of land in the future.

Much effort has been invested in the last five years to improve the availability and quality of drinking water throughout

Karakalpakstan. Even so a significant number – perhaps about half - of rural homes still lack fresh running water. More

than 80% of homes have a pit latrine.

Work and Unemployment

In 2003, 33% of employment in Karakalpakstan was in agriculture, 25% was in health, education, science, and culture, 8.8% was

in construction and another 8.8% was in industry. However, as elsewhere in Uzbekistan, only 80% of jobs are permanent as opposed

to seasonal or temporary.

Consequently Karakalpaks who are lucky enough to have a job are most likely to work in agriculture. During the 1990s the

former State and collective farms were transformed into independent farm cooperatives or shirkats, with employees

turned into stakeholders. Hopes for improved farm productivity failed to emerge and now these co-ops are being disbanded and

privatized into a larger number of small farms, or ferms. Agricultural workers now have some of the lowest incomes

and many still face continued uncertainty through this difficult transition period.

The second most likely occupation is to work for some agency of the State, such as a school or hospital, for the police, or in

a regional government office.

However work alone does not guarantee escape from poverty. Wages are poor – the average wage income in Karakalpakstan is about

half that for Uzbekistan as a whole. The average monthly salary ranges from $25 to $150, but can be less. Some jobs offer only

the minimum legal wage of 69,000 som per year, impossible to live on. To make matters worse, most organizations suffer from a permanent

cash crisis so wages are paid several months in arrears.

Most families, even the wealthy, attempt to supplement their official income in various ways. Those with a garden or back yard

grow some vegetables and fruit of their own, and will probably keep some chickens and perhaps some goats for milking. Even in

No'kis it is common to see families with turkeys, or a few sheep or even a cow. Those lucky enough to have a land plot can sell

surplus food at the bazaar. Children might operate a trolley service at the local market, drivers will undertake casual taxi

work, and unemployed men and women may look for temporary short-term or day work as ma'rdika'r or hirelings. Some seasonally

travel to Kazakhstan where there is more and better paid work. Others participate in the black economy.

There are a few entrepreneurs struggling against the odds to run their own businesses – shopkeepers, market traders, restaurant

owners, shayxanshı, and so on. Despite government attempts to stimulate private enterprise the self-employed operate

in a climate instinctively hostile to private business, with illogical rules and regulations that make it virtually impossible to

run a business without breaking the law. Constantly harassed by officials, police, inspectors, and tax men, only bribery and

bending the rules keeps them in operation. Business registration alone involves ten official authorizations, the provision of

about 50 documents, and perhaps 1.5 million soms in fees. Consequently many operate their businesses unofficially.

Most wheeler-dealers find it easier to operate in the black market, smuggling in gasoline or domestic appliances from Turkmenistan,

where they are much cheaper, or exchanging dollars for som.

Unemployment is very high. How high nobody knows – official statistics are worthless as the majority of unemployed do not register

with an employment agency. Many others are underemployed, doing casual work on a daily basis, or odd jobs on a cooperative farm.

Médecins Sans Frontières has estimated that unemployment combined with underemployment might amount to an amazing 70% of the workforce.

A recent detailed survey in the Karakalpak village of Madeniyat near Aq Man'g'ıt found that among 20 households the number of unemployed

and underemployed exceeded the number of employed: out of 50 adults, 18 were employed or self-employed, 10 were unemployed, 11 had

irregular work, 7 were pensioners, and 4 were housewives. The unemployed included several young women. Unemployment tends to be higher

in rural areas and is especially high among 16 to 25-year olds.

|

Young Karakalpak boy near Kegeyli weeding the new spring crop.

One remnant of the Soviet era is the practice of so-called voluntary labour. Every year schoolchildren, students, and government

employees are required to provide several weeks of unpaid labour for the State. They are mainly utilized for manual work, either

preparing the cotton fields for planting or assisting with the cotton harvest. Students are bussed into rural areas with a police

escort, where they earn 100 to 200 soms a day (10 to 20 cents). Despite the hard work many appear to treat it as an

enforced holiday, making the most of the social side of the event. Some see it as a right of passage to adulthood.

Only a command economy would consider using qualified technicians, administrators, and secretaries as agricultural labourers. It is

a bizarre sight for visitors to see a group of hospital workers, dressed in white gowns close to their ambulance, weeding a roadside

verge by hand!

Income and Consumption

Karakalpakstan ranks fourteenth out of the fourteen regions of Uzbekistan for economic development. Within those fourteen regions

Karakalpakstan has the lowest per capita monetary income, standing at only 58% of the national average and only 40% of the average

for Tashkent city. As already noted Karakalpaks have been particularly hard hit by the overall decline in incomes since independence.

Some Karakalpaks note that in the past an average salary could buy 5 or 6 sacks of flour, but today it will only buy one. A good

monthly salary is about 40,000 som, equivalent to $40 in hard currency but probably enough to buy about $260 worth of goods

measured on a purchasing power parity basis. However an agricultural worker is likely to earn about 6,000 som a month, not

enough to support a family.

In 2003 the World Bank estimated that 36.4% of the population of Karakalpakstan was poor and unable to meet basic consumption needs

(as opposed to 27.5% for Uzbekistan as a whole and 9.2% in Tashkent). Roughly a third of these people are living in extreme poverty.

Consequently Karakalpaks do without the electronic shops, clothing boutiques, and fast food restaurants that are increasingly common in

Tashkent.

The town or village bazaar is the main place for shopping for food, clothing, and utensils. No'kis central bazaar is by far the largest,

but Shımbay, Xojeli, Qon'ırat, Biruniy, and Bostan all have big town markets. Many regions also have a large Sunday livestock market –

the mal bazaar – where people may also be selling staples such as rice, grain, pulses, and of course, chickens, ducks, and geese.

There are also small shops, or du'ka'ns, and kiosks, especially in No'kis, selling processed foods such as dried sausage, cheese,

biscuits, fruit juices, beer, and vodka. Du'ka'ns in rural areas are often poorly stocked. Although there are several Western-style

supermarkets in Bukhara, none currently exist in No'kis.

|

Small shop or du'ka'n in the centre of Kegeyli.

As already mentioned, it is unusual for Karakalpak families to spend money on an evening of entertainment downtown. No'kis has most of

the major entertainment facilities, including up to a dozen restaurants and cafes, many small shayxanshı, the important Berdaq

Theatre, some cinemas, a puppet theatre, an outdoor amusement park, a new aqua park, and several internet cafes, mainly frequented by young

boys intent on playing violent computer war games. There are some provincial cinemas in towns such as Taxta Ko'pir and Moynaq, which open infrequently.

Clothing

Karakalpaks mainly wear Western-style costume and much of this is purchased on the bazaar. Many women buy printed cotton or velvet

to make their own dresses.

Men wear trousers with a Western-style shirt, sweatshirt or t-shirt and a jumper or a jacket of some kind. A quilted jerkin or overcoat

is essential for the winter. The majority of men no longer wear hats in the summer. For those that do the most common headwear is a

trilby or a flat cap. Fur caps are common in the winter. A minority of men – mainly the old – still wear a taqıya or skullcap.

Women dress conservatively. In the summer most women wear a long cotton dress with sleeves, made from colourful cotton prints, sometimes

topped with a cotton jacket or with an open waistcoat. In recent years, however, we have noticed an increasing number of younger women

in the city wearing sleeveless cotton dresses. In the winter women are more likely to wear a long dress made of colourful plush velvet

with a long woollen cardigan or an overcoat. Many young women in No'kis are very fashion-conscious and stylish. Some women, particularly

in rural areas, still wear baggy trousers underneath their dress. Women of all ages continue to wear the cotton headscarf, which can be

tied in a variety of ways.

Western-style black leather shoes predominate, but younger men might wear trainers and many women wear plastic sandals in the summer.

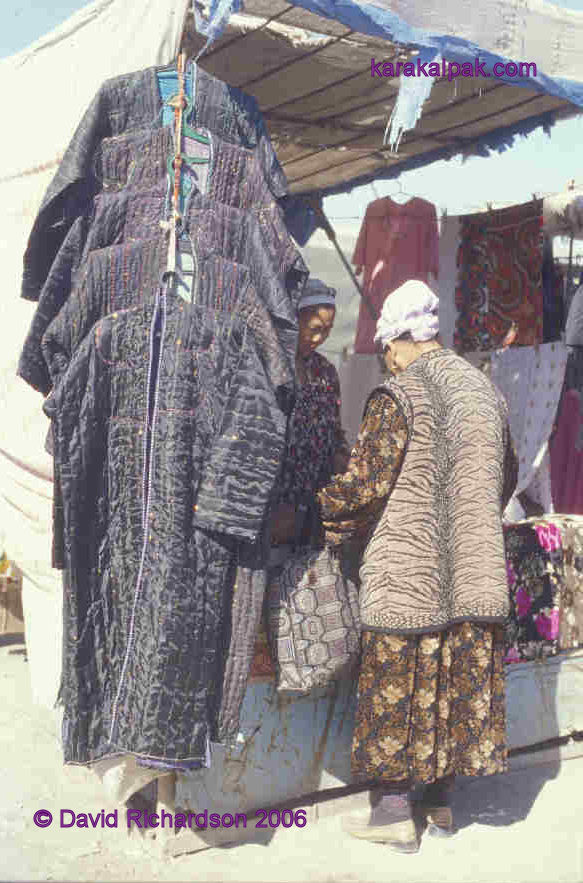

|

Modern shapans on sale at the bazaar.

A few old men and women still wear the traditional quilted shapan. These can be purchased on the market and are normally made

with shiny material and sparkly threads. Younger people might wear the same garment for a special ceremony.

Food and Diet

Karakalpaks generally live on a diet that is rich in carbohydrate. The World Health Organization has estimated the macronutrient

composition of diets in the Karakalpakstan/Khorezm regions to be 64.8% carbohydrate, 21.6% fat, and 13.6% protein.

The main staples are flat unleavened bread or nan, potatoes, rice, and pasta. Meat, sausage, chicken, and cheese are

expensive and are therefore eaten sparingly, even by the well-to-do. Some Karakalpaks even judge their status according to

the amount of meat they can afford to include in their diets. Muslim beliefs do not seem prevent the consumption of either pork

or alcohol in the form of beer or vodka.

Most bazaars have a good selection of good quality vegetables and seasonal salads, such as yellow carrots, potatoes, beetroot,

onions, tomatoes, cucumbers, aubergines, peppers, dill, and coriander. Fruits are particularly good: especially the cherries,

apricots, honey melons, water melons, grapes, and pomegranates.

Karakalpak cuisine is conservative and not that dissimilar to other Central Asian fare. The most frequently encountered dishes

include

- Bes barmaq is boiled horse-flesh or mutton with small cut pieces of pastry boiled in broth, lavishly sprinkled with

dill, parsley and coriander. |

- Plov is a common staple food for everyday meals but can be elaborated for special celebrations. It consists of

chunks of fried mutton with onions, thinly shredded yellow turnip or carrot and rice steamed together in a large iron pot. |

- Shashlık, also known as kebabs, are skewered chunks of mutton or pork barbecued over charcoal and served with

sliced raw onions and nan. |

| - Ju'weri gu'rtik is a pasta dish made with ju'weri (jugary) wheat rather than normal wheat. |

- Kesbas is made of pasta cut into slices and boiled in water with meat, carrot, onion, potato, tomato and of course

salt. It is traditionally made with sheep’s head. |

- Samsa is a pastry pie stuffed with meat and onion or pumpkin, potato, cabbage, mushrooms, or nuts and is baked in

a tandır. |

- Mantı are large dumplings stuffed with finely chopped meat, seasoned with various spices and a large amount of onion,

and then steamed over water. |

| - Shorpa is a meat and vegetable soup. |

| - Lagman is a thick noodle soup with thinly sliced fried meat and vegetables. |

Sweet desserts are rare. A meal finishes with some melon, water melon, candy, or dried fruits and nuts. The usual drink is black or

green tea served with sugar.

Officialdom

Karakalpaks live in a highly bureaucratic society where authorizations and permits are required for almost any activity. Corruption

is widespread. Uzbekistan operates as a police state and high numbers of policemen are noticeable everywhere. It is impossible to

travel without papers, especially as there are about 15 provincial border road-police checkpoints between No'kis and Tashkent. Even

national citizens must register with OVIR, the immigration department, if they come from another city, even if they are just visiting relatives.

In Karakalpakstan every official has power and many are unwilling to carry out their responsibilities without some additional

“lubrication”. It is almost impossible to get a job, be admitted to hospital, have a telephone installed, enter university, become

a policeman, get a business license, or apply for a passport or other official document without being asked to pay a bribe.

Transport

Only a minority of Karakalpak families have a private car. For Uzbekistan as a whole 25% of households have a passenger vehicle.

In Karakalpakstan the proportion is perhaps 15%. A new Uzbek-manufactured Daewoo costs $4,000 upwards and is therefore limited to

the very wealthy. Most car owners drive an old Lada or occasionally a larger Volga or Moskvich.

The main trolley bus route which used to run through the centre of No'kis.

The majority of local people travel by bus or minibus. Most large residential areas have a jonelisli service, a minibus

that follows a fixed route into the town centre or local bazaar. There used to be a trolley bus service operating along the main highway

running through the centre of No'kis. Special bus services are laid on for Sunday markets. Larger buses operate on long distance

routes, connecting No'kis to Bukhara, Samarkand, Tashkent, and Almaty, the latter journey taking over 36 hours.

A small bus brings villagers to the Sunday livestock or mal bazaar in Taxta Ko'pir.

In rural areas many farm workers still use a donkey and cart, or arba, for travelling to market. In remote regions of

the delta people will walk for kilometres from their homes to a bus stop on the main highway. Surprisingly bicycles seem to be quite rare.

Karakalpakstan lies on one of the main railway lines linking Tashkent to Moscow. The main stations are at Qon'ırat, No'kis, and To'rtku'l.

It takes about 26 hours to get from No'kis to Tashkent by rail. There is a special terminal north of Qon'ırat for loading vehicles onto

the train. The most northern station in Karakalpakstan is at the remote border settlement named Karakalpakstan on the Ustyurt plateau.

No'kis has a small modern airport with daily connections to Bukhara, Samarkand, and Tashkent. Prior to independence subsidized air

travel was affordable for most middle-class people. Today prices are much higher. A return flight from No'kis to Tashkent is equivalent

to over three months salary for most people. Consequently only the wealthy, officials, or foreign tourists can justify such an expense.

Education

Karakalpak is the main language spoken and literacy is very high, claimed to exceed 99%. About 30,000 infants (14% of all pre-school

age children) attend 386 kindergartens across Karakalpakstan. In theory all children attend school from the ages of 6 or 7 and spend

4 years at primary school and 5 years at secondary school. In reality school enrolment has fallen since Soviet times and the schooling

system has declined. It is common to see school-aged children during school hours either at home, working in bazaars, or selling

goods by the roadside. There are some 350 to 375 schools in Karakalpakstan teaching about 125,000 students in the Karakalpak language.

There are of course many other schools teaching in Uzbek and even Qazaq. In the past many Karakalpak schools taught Russian as a

second language, but today they might teach English or German instead.

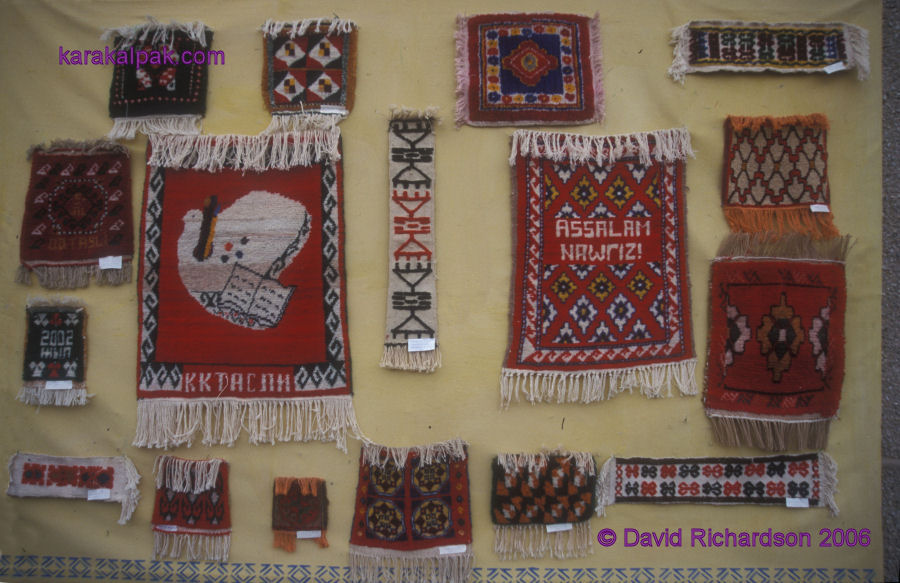

|

Presentation of students' work at a school in No'kis.

Their project focused on the traditional culture and crafts of the Karakalpak people.

Textbooks are free in the first year but have to be purchased thereafter. An increasing number of schools in No'kis have internet

connections and many are involved in projects linking them to schools in other countries.

The few centres of higher education are all located in No'kis. There is one university, the Karakalpak State University named after

Berdaq, and one Pedagogical Institute for teacher-training. But annual tuition fees can be of the order of 300,000 soms,

an impossible amount for the poor. Enrolment into higher education is lower in Karakalpakstan than in the viloyatlar of

Uzbekistan, with the two exceptions of Surkhandarya and Kashkadarya.

Educational development is a national priority and is a focus of aid funding. Recently a large new sports college was opened on the

outskirts of No'kis.

Healthcare

The health of many Karakalpaks, especially in rural areas, is not good. In addition to the consequences of poverty, such as poor diet,

water quality, and a hard life Karakalpaks suffer from the environmental degradation of the Aral delta caused by intensive cotton

farming and the desiccation of the Aral Sea. Anaemia has become almost universal in pregnant women and rates of respiratory and

diarrhoeal disease, heart and kidney disease, thyroid problems, and cancers are all abnormally high. A large proportion of Karakalpak

children look distinctly unhealthy.

The Karakalpaks benefited from a strong, functioning healthcare system under the Soviets, which has fallen into considerable neglect

following independence – mainly due to massive cutbacks in government heath expenditure. In the words of Medécins sans Frontières:

“General hospitals in Karakalpakstan remain in an appalling state of disrepair, with poor sanitation, unusable latrines, and poor

healthcare waste management.” Many Russian doctors and clinicians have left the country, drugs and medical supplies are in short

supply, and diagnostic equipment, if it exists, is antiquated.

While Karakalpaks in No'kis at least have access to a hospital, those in the countryside may have to travel far to find a doctor.

Many rural families survive on homemade potions and cures.

Welfare

Despite widespread poverty, begging is hardly ever seen, apart from a few gypsy families, or lo'lilar around No'kis bazaar.

There is no State social security system as such and people’s first line of support comes from their extended family, friends, and neighbours.

Coinciding with the removal of food subsidies in 1994, the Uzbek government introduced a new social assistance scheme based on the

traditional pre-Soviet local community groups, known as mahallas in Uzbek or ma'ka'n ken'es in Karakalpak. These

committees consist of a group of elders who try to solve social problems and conflicts within the community. The chairman is elected,

but other members can only be nominated by the local district executive or ha'kimiyat.

Under the scheme the local ma'ka'n ken'es receive funds from central government. Families in need can apply to the

ma'ka'n ken'es for assistance and, depending on merit, can be granted a cash income for up to three months. The main priorities

are families with a large number of children, the unemployed or disabled, single mothers, widowers, and pensioners.

In 1995, the first full year of operation, some 28% of households in Karakalpakstan received payments.

Old Age and Death

The official retirement age is 60 for men and 54 for women. Life expectancy at birth in Karakalpakstan is over 69, so most Karakalpaks

live to a good age. However many old people have lived a tough life and by Western standards look much older than their years. At

least under the Soviet system the retired were paid a fair state pension. However pensions were cut substantially in the 1990s,

one of the many government economy measures introduced after independence.

Because many of the elderly continue to live with their families they tend to remain active, helping with the household chores,

cultivating the garden, or looking after their grandchildren. People in their 80s are still a storehouse of knowledge – they can

remember as far back as the period of collectivization when the traditional way of life disappeared with the introduction of organized

intensive agriculture.

Karakalpaks are overwhelmingly Sunni Moslem and they deal with death in a typically Islamic fashion. After a death the relatives and

friends of the deceased are informed and come to pay their respects to the bereaved family. The men congregate outside the house so

that neighbours can see that someone has died, while the women stay inside. The body is washed and wrapped in a cloth. A mullah

is invited and the most honoured relative or neighbour reads passages from the Qur’an. Burial normally takes place within one or two days,

depending on whether it is summer or winter. Only the men accompany the deceased to the burial ground. The women visit the grave on the

following day.

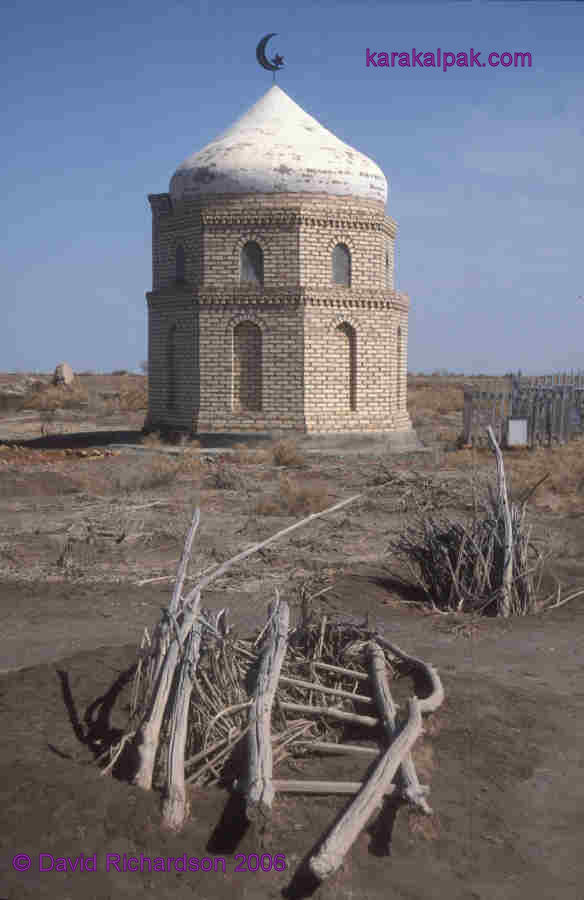

|

The huge mazar on the natural hill of Mizdharkhan, close to the Turkmen border.

Cemeteries or mazars are usually located in prominent and isolated locations and some have been in use since antiquity.

A high location is preferred such as a natural hill or the top of the tchink, but since much of the Aral delta is flat

this is generally not possible. People also favour a site that contains the grave of a revered cleric or holy man. The massive

and ancient mazar on the hill at Mizdakhkan is the most famous Karakalpak burial site. Another important one lies at the

base of the Ustyurt just outside of Qon'ırat. People from the same clan tend to use the same mazar.

The graves of the rich and poor sit side by side in a mazar at Qıpshaq.

A wealthy family might have a grand brick-built mausoleum, but most ordinary families erect a simple grave with a painted fence and

perhaps a plaque with an image of the dead person. A pauper has just an earthen grave marked only with the funeral bier surrounded

with thorn branches to discourage foraging animals.

Conclusion

Karakalpaks continue to follow a conservative and traditional lifestyle centred around the family. In a system where government

social assistance is minimal, both the close family and the wider extended family remain the bedrock of Karakalpak society. The

senior members of the family are respected figures of authority and exert a strong influence over their less senior relatives.

Bad behaviour and crime are not tolerated. People behave conservatively and generally dress conservatively.

Most Karakalpaks look back to the Soviet era with nostalgia. The majority openly acknowledge that life has become much harder

since 1991 – unemployment has increased due to the collapse of previously subsidized factories and the State has drastically

reduced the number of government employees; savings have been destroyed by hyper-inflation; prices have risen faster than incomes;

wages are continually paid in arrears; and the provision of services like healthcare and a college education are no longer free.

Although it is easy to see the signs of economic progress in Tashkent, it is far harder to be optimistic about the future in Karakalpakstan.

With no outlet for protest or complaint, most people tolerate the situation with resignment. In our experience the elderly are the

most likely to voice their complaints aloud – perhaps they know they have nothing to lose. As throughout the Soviet era, personal

advancement is not achieved through initiative or making proposals for positive change but through obedience and acquiescence.

Postscript

We see the world through English not Karakalpak eyes. However we do not regard this as a handicap. Quite the contrary as we believe

it is far easier to be objective about someone else’s society than your own.

Just like any other researcher we can only describe Karakalpak life today from a combination of our own direct observations and enquiries,

and from scientifically gathered statistics.

Our objective is to give neither an idealistic nor an overtly pessimistic picture of Karakalpak life, but to provide an accurate and

balanced summary of what modern life is like for Karakalpaks today. If you can provide us with additional factual or statistical

information, please contact us.

Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms

To listen to a Karakalpak pronounce any of the following words just click on the one you wish to hear. Please note that the dotless letter

'i' (ı) is pronounced 'uh'.

References

Bentvelsen, K, Socio-Economic and Gender Survey of Madeniyat, Uzbekistan, Femconsult, The Hague, November 2005.

Coudouel. A, Marnie, S. and Micklewright, J., Targeting Social Assistance in a Transition Economy: The Mahallas in Uzbekistan, UNICEF, Florence, 1998.

Ilkhamov, I, Consultations with the Poor, Participatory Poverty Assessment in Uzbekistan for the World Development Report 2000/01, EXPERT Center for Social Research, Uzbekistan, May 1999.

Médecins Sans Frontières, Karakalpakstan: A Population in Danger, Tashkent, 2003.

Republic of Uzbekistan, Living Standards Strategy for 2004 – 2006 and Period up to 2010, Tashkent, 2004.

Saidova, G., and Cornea, G. A., Linking Macroeconomic Policy to Poverty Reduction in Uzbekistan, Center for Economic Research, Tashkent, 2005.

UNDP, Uzbekistan: Human Development Report, UNDP, Tashkent, 2000.

UNDP, Uzbekistan - 2005: Human Development Report, Decentralization and Development, UNDP, Tashkent, 2005.

World Bank, Uzbekistan Living Standards Assessment, Report Number 25923-UZ, Human Development Sector Unit, Europe and Central Asia Region, World Bank, Washington DC, May 2003.

World Bank, World Development Report 2006, World Bank, Washington DC, 2005.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|

|

![]()

![]()