|

Contents

Traditional Festivals and Holidays

The Summer Migration

Mereke Folk Festivals

Religious Festivals

Modern Festivals and Holidays

Seasonal Holidays

Religious Festivals

Soviet-inspired Holidays

Official Uzbek Holidays

Enforced Cultural Change

Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms

References

Traditional Festivals and Holidays

While they lived on the Syr Darya, the Karakalpaks followed the same folk calendar as the Qazaqs of the Lower Horde. However after they came

under the authority of Khiva their religious calendar was realigned with that of the Khorezmian Uzbeks. The imposition of Soviet rule led to

agricultural development and modernization and a consequent rapid decline in the traditional way of life. It also led to the official prohibition

of all Islamic religious festivals along with the ancient Zoroastrian festival of Navrus or Nawrız in the Karakalpak language. Holiday festivals were not abandoned but were

reassigned to Soviet celebrations, such as the anniversary of the October Revolution and the Day of International Worker Solidarity.

Although our information concerning the annual cycle of Karakalpak festivals and holidays prior to the Soviet period is quite good, our knowledge

about what occurred during those festivals is limited by a lack of detailed historical evidence. Ethnographers have attempted to glean some

indications from surviving traditions and from the folk memories of the Karakalpak elderly.

The Summer Migration

One of the most important events in the Karakalpak year was the summer migration from the winter settlement to the summer pastures.

The traditional way of life for the Karakalpaks was quite different from that of the neighbouring nomadic livestock-breeding tribes and evidence

shows that it was followed from at least the early 18th into the early 20th century. It was based upon a semi-settled, semi-nomadic, mixed

pastoral-agricultural economy. The Karakalpaks primarily raised cattle for milk, meat, hide and horn – sheep and camels could not cope with the

marshy conditions of the delta. However they only grazed their livestock during the summertime. During the harsh delta winter they had to

shelter their livestock and use their agricultural by-products for forage: hay, wheat and millet straw, ju'weri stems (sorghum) and cane,

along with reeds or qamıs harvested from the marshes. In the spring they used their cattle to till the land. Each clan or sub-clan would

have a wintering ground, qıslaw, and a summering ground, jazlaw, usually not too far apart from each other. In the winter, the

yurts would be erected inside a windbreak fence for protection, and another fenced enclosure would be built for the cattle. In the spring they would

move their yurts to the summering ground, close to the cultivated areas, allowing their herds to graze on the surrounding marshes and pastures.

After cultivating the land during the summer, the fodder would be harvested and moved to the wintering ground by bullock cart. In some cases crops

were also grown at the wintering ground.

We have so far failed to find any photographs illustrating the Karakalpak summer migration.

The Savitsky Museum photo archive contains several images annotated as "nomads", clearly undertaking their seasonal migration.

There is no information indicating the ethnic group involved, the geographical location, or the date.

The images look like Qazaq women and children transporting their yurts on camels. Their costume dates to the 1930s or early 1940s.

The Russian representative Lieutenant Dmitry Gladyshev and his surveyor Ivan Muravin visited the Karakalpaks living on each side of the Syr Darya

in 1740 and 1741. Although they did not precisely describe the semi-nomadic lifestyle of the Karakalpaks, they did highlight their economy of mixed

livestock-breeding and agriculture. The landscape in which they then lived was composed of lowlands with black soil composed of silt and sand surrounded

by extensive swamps and marshes where the reeds were cut for cattle fodder. The Karakalpaks roamed with their livestock but also ploughed the

lowlands using bulls, sowing crops of wheat, barley and millet that were irrigated by means of water channels fed from the adjacent lakes and rivers.

Peter Rychkov, whose writings were published a little later in 1762, summarized the Karakalpaks dual existence:

"...they live in yurts during the winter and in summer they roam;"

Although Gladyshev and Muravin made no reference to defensive structures, Rychkov noted that the Karakalpak winter settlements on the lower

Syr Darya were surrounded by earthen ramparts. Known as qalas, these settlements provided a defence against attack by Qazaq nomads:

"The Karakalpaks have raised entrenchments of earth, which offer them protection against Kyrgyz-Kazakh attack. In the winter they withdraw into

the reeds around the Aral Sea."

It is likely that the need for these qalas depended on the security situation at any time. Pavel Ivanov stressed that during the 18th century

the Karakalpaks had no permanent settlements and that such defensive structures were purely temporary. However the security of the Karakalpaks

deteriorated significantly after 1743 because of Qazaq dissatisfaction with their decision to negotiate an independent sovereignty agreement

with Russia.

Johann Georgi did not visit the Karakalpaks himself but did publish a little more information on their semi-nomadic lifestyle in 1776-77, presumably

obtained through a knowledgeable third party:

"The constitution of the Karakalpaks is very similar to the Bashkirs; like the latter they have permanent huts where they spend the winter; during

the summer they are peddlers and travel with portable felt huts; they plough some small fields but the care of their herds occupies them to advantage.

They have little in the way of horses and prefer oxen and cows, which they also use for harnessing and mounting."

After they had migrated into the Amu Darya delta, the Karakalpaks continued to build their winter qalas although now the military threat

was posed by marauding Yomut Turkmen rather than by the Qazaqs. The 1873 Khiva Expedition described the situation thus:

"There are no really settled villages in the Shımbay district. All the population of Shımbay district (even the Uzbeks) live in

kibitkas, moving them from the ploughed fields to their pastures. In winter they group several hundred kibitkas in certain sorts

of hill towns (qala), which they build through their common efforts, erecting ramparts and moats for defence against nomadic gangs of robbers."

Riza Quli Mirza provided a similar picture in 1875:

"Karakalpaks are quite settled... Their summer migration means that they move their yurts to the ploughed fields; in winter they carry their yurts

to qala or enclosures, where several hundred yurts may be settled as a defence against forays ..."

Nikolay Karazin, a participant in the Amu Darya expedition of 1874, discovered that the nature of Karakalpak qıslaw or winterings varied

in different parts of the delta. Thus along the banks of the Ul'kun Darya in the northern delta, the winterings were no more than large villages

of kibitkas, surrounded by the herds of livestock. South of Qusxanataw the winterings were surrounded by adobe walls, while the winterings

at a small village on the Dzhak-Kazak canal had a quadrangular court surrounded by a high clay wall that had an overhanging roof on its internal side.

By contrast, the vast winter settlement in Shımbay consisted of some 40,000 kibitkas crammed within an encircling 1½ km-long

defensive adobe mud wall. During the winter the Russian fort at No'kis was equally crammed with Karakalpak yurts:

"There was only space for a foot between these nomad tents..."

The Karakalpak way of life in the Amu Darya delta was described in more detail in the Turkestan Gazette of 1875:

"The entire population of the [Shımbay] section, not just the Karakalpaks, live in nomad tents, moving the latter from the land on which they

are occupied with arable farming into other places for the pasturage of cattle, being grouped together for the winter in several hundred nomad

tents erected in special kurgans (qala), which they arrange by means of a general workforce, building earthen walls and ditches for protection

from the vagrant gangs and predators. Inclined by their nature and habits to permanent residency, the Karakalpak population are more like nomads

given their situation and their means of life, the only difference being that the range of their nomadism is small. Karakalpaks exclusively live

in the nomad tents, but if they have places for saklya [a type of Caucasian mountain hut], then they use such cold structures for the

accommodation of different reserve supplies, horses, etc."

Having survived the harsh delta winter and the risk of kidnap or livestock theft, the migration to the summer pastures was a major festive occasion.

The whole clan was in a holiday mood and dressed in their best clothes. Aleksandr Kaulbars, who arrived with the Russian forces under General

Konstantin Kaufmann, observed the unique features of this Karakalpak summer migration in the locality of Terbenbes in Muytenov (now Moynaq region)

in 1873:

"during the day, when the migration has been assigned, everyone is directed to wear their best clothes and dresses and to decorate themselves for

the holiday; the entire village with all its belongings moves, observing the rites that have been strictly established for centuries..."

Kaulbars continues:

"The herds and flocks were moving ahead: fine bulls, cows, calves, goats and sheep ... and then the long line of arbas harnessed to one or

sometimes two strong bulls."

The scientific study of the Karakalpaks began from the mid 1920s onwards. However by the time that researchers such as Anna Morozova had arrived in

Karakalpakia, not only had these summer migrations come to an end but there was no longer any need for the qala winter strongholds. Our

understanding of the traditional summer migration holiday comes from the study of the surviving traditions and rites associated with the erection of

the summer yurt as part of the field research conducted by the Khorezm Expedition in the 1940s and 1950s.

The placing and erection of the yurt was accompanied by various rites and ceremonies, including sacrifices, games and contests. For example in

order to protect the family from evil spirits and to make their home wealthy, the poles of the yurt were smeared with butter and salt and pepper.

Various plants and grasses were hung up to the wall lattices. Once the framework was assembled, long ropes were fastened to the shan'araq

to make a swing for the children. This served the dual purpose of entertaining the young and ensuring that the uwıqs were tightly

connected to the shan'araq, thus giving the entire framework greater stability. The operation of the swing was strictly proscribed – the

occupants of the swing had to be an opposite pair, namely a boy and a girl. They had to stand on the swing and arrange their feet so that one leg

of boy would rest on the board of the swing between the legs of girl. Furthermore the axis of swing had to be from the entrance to the rear wall of

the yurt, in other words from north to south.

A giant swing erected for a folk festival at Shılpıq, in southern Karakalpakstan around 1980.

Such swings were once widespread throughout the peoples of Central and Southeast Asia as a form of entertainment at the time of holidays, weddings

and feasts. They seem to be a relic of an ancient cult of fertility.

Sometimes instead of a swing, people hung bags of wheat and stones from the shan'araq. In addition to strengthening the yurt framework these

too were probably once associated with supernatural beliefs, wheat being a symbol of abundant prosperity and stones often being considered endowed with

magical properties.

A Karakalpak family in a holiday mood during the erection of their summer yurt.

In the family garden in a residential

district of No'kis, 2004.

Of course once the yurt was erected and decorated it was time for the family to enjoy a feast to celebrate a successful summer season. Even today,

families still prepare a special festival meal after erecting their summer yurt such as bes barmaq (meaning five fingers), a dish of boiled

mutton served with pasta or noodles, that is eaten collectively from a single dish by the whole family using their hands.

Mereke Folk Festivals

The Karakalpaks sometimes organised traditional communal folk festivals known as mereke. They involved traditional musicians, storytellers,

mummers, various competitions for testing the strength of horses, wrestling, ram fighting, and possibly the chaotic game of ılaq oyın

(see below). Women were conveyed to the festival in the traditional two-wheeled carts known as arbas.

A rope walker at a festival in Khiva, not later than 1890.

Photographed by the French photographer M. Hordet who visted Turkestan during the late 1880s.

Anna Morozova referred to a most unusual contest that sometimes took place at these events. To test the strength of horses they yoked an animal to an

arba cart which was linked with a further two carts behind, thus creating a six-wheeled vehicle. A platform was constructed on the top and

a yurt erected upon it. Musicians and performers then climbed aboard to sit around the yurt. The horse was then driven over a defined course, urged

on by shouts from the crowd.

A major festival or fair, probably in Khiva, in the first decade of the 20th century.

Note that all the men are segregated from the women, the latter being positioned on the roof tops.

Photographed by the Khivan Uzbek photographer Xudoybergan Devonov, born in Khiva in 1879.

Sadly we lack any historical description of such traditional Karakalpak events. Our knowledge primarily comes from the folk memory of elderly

Karakalpak people. Some idea of these events might be gained from photographs of similiar festivals held in nearby Khiva.

Religious Festivals

In the past the Karakalpaks seem to have been more devout Muslims than the neighbouring nomadic Qazaqs. Peter Rychkov tells us that in the mid-18th

century:

"... although they have their khans amongst them, the aforementioned have almost no power, although their khodjas - of whom there are very

many amongst them - have great power and are held in great respect since they are recognised as the descendants and students of Mohammed."

He also noted that the Karakalpaks had more Islamic religious scholars and more people capable of reading and writing. They therefore understood the

Mohammedan religion and its laws better than the Qazaqs.

Johann Georgi wrote that: "The Karakalpaks are Mohammedans and are well educated."

So important were some of the Karakalpak clergy that they frequently fulfilled the role of political leaders. This explains why during their

negotiations with the Russian representative Ivan Gladyshev in 1740, the 30,000 kibitkas of the Lower Karakalpaks were represented by ten

senior elders, four of whom were xojas and two of whom were shayıqs.

After their forcible settlement in the Amu Darya delta in the early 19th century the Karakalpaks came under the control of the Khivan court, which

strictly upheld the Moslem faith. Surprisingly the Karakalpak clergy were rarely mentioned in the Khivan chronicles in relation to the social and

political life of their people, suggesting that they might have lost some of their former predominant position.

Ivanov suggested that the Karakalpaks may have come under the influence of the Khivan clergy – the ishans – who had their centre in Khiva

and were primarily Sufis. The Khivan chronicle records that one of the Khivan ishans named Mohammed voluntarily secluded himself in the

Karakalpak region along with his "flock". Certainly the local Karakalpak priests and shamans, variously known as iyshans, axuns,

xojas and shayıqs, exercised considerable influence throughout the delta. Funded by official religious taxes, income from religious

lands, and fees charged for the execution of religious rites during the religious holidays, they were relatively wealthy by Karakalpak standards.

Landless peasants cultivated the vaqf lands of mosques, giving part of the harvest to the iyshans. In addition, the population had

to pay the mullahs for reading prayers and were penalized for the failure to observe proper religious customs. Qazıs and rayıs'

policed the population with regard to Islamic law and often abused their power, inflicting various penalty measures for the slightest offence. They

were also not averse to taking bribes.

Colonel Leonid Sobolyev discovered that the Karakalpaks preserved many orders and rules based on their national customs. During a discussion with

some Karakalpak religious leaders in Shımbay in 1874 he asked about the difference between life in the Amu Darya delta and that on the Syr Darya.

One religious leader answered:

"Here the land is Moslem; fasts are observed, there [on the Syr Darya] there was unbelief."

The Karakalpaks established many mosques and some medressehs throughout the populated part of the delta. However most mosques were little more than a

yurt, while medressehs were simple single storey flat-roofed adobe buildings. Some of these sites became special "holy places" and had rooms for the

pilgrims who came to worship the local "saint" and associated settlements for the entire community of iyshans. Examples include the medresseh

in the village of Qara Qum Iyshan in the northern delta, reputedly founded by the descendants of Qara Qum iyshan, and Iyshan Qala in Kegeyli

region, named after Imam iyshan. The ruins of the latter can still be visited close to Xalqabad. These centres were funded from income earned

from the religious lands as well as from the offerings of pilgrims.

We know from the works of Shir Mohammed Munis (1778-1829) and his nephew Mohammed Riza Agahi (1809-1874), written during the period from the early to

the late 19th century, that the Khanate of Khiva recognised both the Islamic or Hijra calendar and the local Khorezmian calendar based on the

twelve houses of the zodiac.

The Islamic calendar is known as the Hijra calendar because the year of the Hijr, the withdrawal of Mohammed and his supporters from

Mecca to Medina, was chosen as the very first year. The Islamic year is based on the lunar cycle and is therefore only 354 days long. Consequently

the dates of specific events in the Islamic calendar move forwards by about 11 days every year in the Gregorian calendar. The sequence of the months,

according to their Khorezmian spelling, was as follows: Muharram (meaning forbidden), Safar (empty), Rabi' Awal (first

spring), Rabi' Thani (second spring), Jumadi Awal (first freeze), Jumadi Thani (second freeze), Rajab (to respect),

Sha'ban (to distribute), Ramazan (parched thirst), Shavval (to be vigorous), Z'ul-Qa'da (month of rest), and

Z'ul-Hijja (month of Hajj). The start of each month is determined by the human sighting of the new moon and can therefore vary

from location to location around the globe. Munis seems to have adopted this Hijra calendar from the reign of Khan Eltũzer Muhammad

(1804-06) onwards.

The Islamic year begins with the Islamic New Year, Al Hijra, on 1st Muharram. It is followed 70 days later by the Prophet's birthday,

Mawlid-un-Nabi, celebrated by Sunnis on the 12th of Rabi' Awal, the third Islamic month. Ramazan, the ninth and holiest month

of the Islamic lunar calendar, during which the Qu'ran was revealed to the Prophet, occurs just under six months later.

Following the sighting of the new moon, true believers are meant to abstain from all food, drink, tobacco and sexual intercourse between the hours of

dawn and sunset.

Many families break the daily fast together with a communal evening meal, started after the official sunset and known as the awız ashar,

literally the opening of the mouth.

The final month of Z'ul-Hijja is dominated by the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, which every able-bodied Moslem is expected to do

at least once in his or her lifetime. Once in Mecca pilgrims undertake the greater Hajj on 8th Z'ul-Hijja, first travelling to

Mina and then visiting the plain besides Mount Arafat. The 10th Z'ul-Hijja is the first day of Eid ul-Adha, the Festival of

Sacrifice. Pilgrims stone the jamarah wall in Mina and afterwards animals are sacrificed on their behalf.

The local Khorezmian zodiacal calendar was based on the solar year of 365 days and had twelve months or "mansions", each described by means of its

Arabic name. The year began with the first month of Hamal (Aries), and was followed by Thawr or Sawar, Jawza,

Saratan, Asad, Sunbule, Mizan, Akrab, Qaws, Jadi, Dalv, and Hut.

However the zodiacal year in Khorezm was not synchronized with the zodiacal year elsewhere – it began 22 days earlier than it did in the Khanate

of Bukhara or in Iran.

During the 17th century a third type of calendar seems to have been in use. When referring to dates in this period, Munis used the Central Asian

animal calendar, adopted from the Mongolian or Chinese calendar. This is based on the twelve-year cycle, consisting of the years of the Mouse, Cow,

Leopard, Hare, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Sheep, Monkey, Hen, Dog, and Pig.

Navruz

One of the most important official holidays was Navruz, meaning new day or time. Navruz was the start of the Persian year and is

a relic of the ancient Zoroastrian culture that was prevalent throughout Central Asia, including the Khorezm oasis, prior to the Arab invasion in

the 7th century. Navruz is said to have been introduced by the Indo-Iranian King Jamshid or Yima, mentioned in the Avesta, and it was

celebrated by the Achaemenids during the second half of the first millennium BC. Although the Arabs virtually extinguished the Zoroastrian religion

in Central Asia, Navrus was subsequently adopted by the Turks from the Sasanian Empire. Houses were spring-cleaned, bonfires were lit on

rooftops and a celebration feast prepared to welcome back the guardian angels and spirits of the dead.

During the 19th century the Navrus holiday in Central Asia was celebrated on different dates according to location. In Khorezm it was

celebrated around the end of February and was known as Navruz i-Khorezmshahi, indicating both its local and its ancient origin. Yuri Bregel

calculated that Navruz i-Khorezmshahi occurred on 28 February 1778, 28 February 1805, 27 February 1810 and 26 February 1812, from

which he deduced that it must have been held on 1st Hamal, the first day of the annual Khorezmian zodiacal calendar. Some confusion has

arisen because Agahi mentioned that it took place on 1st Hut, but this seems to have been a mistake.

Elsewhere in Central Asia people also celebrated Navruz on 1st Hamal, the first day of their zodiacal calendar. However because

their calendars were phased 22 days later, they celebrated Navruz on or close to 21 March. This festival was known as Navruz

i-Sultani, a reference to the solar calendar of the Seljuk Sultan, Jalal ad-Dawla.

According to Agahi, Allah Quli Khan (1825-42) abolished what he regarded as an incorrect local custom and introduced Navruz i-Sultani,

following his return from a raid on Khurasan in 1827. However there seems to have been no change to the local Khorezmian calendar and so, despite

Allah Quli Khan's 1827 command, the late February Navruz holiday seems to have been celebrated in Khorezm into the early 20th century.

According to later ethnographic research among the neighbouring Uzbeks, reported by M. V. Sazanova, Navruz was celebrated in Khorezm

for 25 days, commencing 15 days before the vernal equinox (which took place around 20-22 March) and finishing 10 days after the equinox.

Navruz was a crucial date signifying the start of the agricultural season. The peasants throughout Khorezm, including the Karakalpaks,

calculated their annual agricultural programme from this specific date.

On Navruz it was the custom for Karakalpaks to make a special milky new-year soup called Nawrız go'je. Go'je was traditionally

prepared from a mixture of seven ingredients: ju'weri or sorghum, rice, wheat, milk, oil or butter, salt, and water. However some families

used up to 12 ingredients, including millet, barley, corn, beans, and red pepper. The sorghum, rice and wheat mash were not ground but cooked whole.

Each family tried to entertain as many guests as possible because they believed this improved the chances for a following good harvest. So much go'je was

prepared that people joked: "Anyone unsatisfied after new-year soup will never be satisfied in life."

Go'je soup was eaten collectively by the entire village. Everyone assembled in the local mosque and the soup was dispensed by a respected

villager, normally a man aged around 45 to 50 years old. First to be served were the elderly men and the old women, then the adults followed by teenagers

and finally children. Good wishes were exchanged for good health and happiness so that everyone would survive until the following helping of

Nawrız go'je.

The Uzbeks of Khorezm and some other peoples of Central Asia had a different tradition. This involved the preparation of a ritual dish called

sumalyak, considered to possess magical powers for ensuring a good harvest later that year.

Karakalpaks in some regions celebrated Nawrız by lighting sacred fires and feeding them with tamarisk branches, a relic of the Zoroastrian past.

Oraza Ait and Qurban Ait

Despite their poverty and the burdens placed upon them by the Khivan Khan, the Karakalpaks celebrated a number of other Islamic religious holidays

in addition to Navruz, the most important of which were Oraza Ait and Qurban Ait. Oraza Ait, the Festival of

Breaking the Fast, fell on the 1st day of the Khorezmian month of Shavval, the first day following the ninth and fasting month of

Ramazan, (known as Ramadan throughout the Middle East as well as in the West). Qurban Ait, the Day of Sacrifice, fell on the 10th

day of Z'ul-Hijja, the last Islamic month. It celebrated the last day of the great Hajj during the pilgramage to Mecca, the day

following the pilgrims return from Mount Arafat.

Oraza or Uraza Ait was the annual holiday for celebrating the end of the month of Ramazan. Uraza possibly comes

from the Turkic word for fast – uruç. It is known as Eid ul-Fitr in Arabic, literally meaning the feast of the breaking of

the fast. It was referred to as Fitr 'Idi in the Khivan court. The word eid or 'idi refers to "the time of return" or

something that returns every year and over time has come to mean a festival. The word fitr means "to break".

Traditionally the first day of Oraza Ait began with people dressing in their best clothes and attending communal prayers, normally in the

open if the weather permitted. It was a day for thinking about the unfortunate and, for those who could afford it, making offerings to the poor. In

the Khivan Khanate it was an opportunity for the Khan to exercise clemency. For example Munis' diary entry for 20 June 1822 noted:

"On Thursday, which was the thirty seventh day of his majesty's campaign, the moon of the Festival of Breaking the Fast (Fitr 'Idi) appeared

in the sky. On the morning of the festival, his majesty, out of perfect kindness and clemency, freed the captured enemy soldiers, along with their

families, and sent them to their homes, ..."

Qurban Ait, the Festival of Sacrifice, occurred roughly 70 days after Oraza. The Turkic word qurban means sacrifice.

Those who could afford to do so were expected to sacrifice their best domestic animals as a symbol of Ibrahim's (Abraham's) decision to sacrifice

his son Ismael in response to a command from Allah. Of course this was just a test of Ibrahim's faith and in the end he was allowed to sacrifice a

ram instead.

There was a custom among the Karakalpaks for seven or nine families to cooperate in the slaughter a cow or a bull. According to Islamic tradition

and also popular belief, the sacrifice of a ram would only protect a single person whereas the sacrifice of a cow or a bull would protect seven people.

Consequently seven people from seven families participated together in the sacrifice of a cow, sharing out the meat between them. One family prepared

a feast from the sacrificial meat or sadaka and invited the other six families to join them, along with other relatives and neighbours and, if

possible, the village mullah. It was believed that misfortune would befall anyone who did not share their sacrificed meat with others. At the end of

the feast either the mullah or the most senior person present blessed the master of the house and wished health, strength and longevity to all those

present.

Modern Festivals and Holidays

Today the Karakalpaks have no unique festivals of their own and share their public and religious holidays with the rest of Uzbekistan. Many are held

on the same day each year. However religious festivals are linked to the lunar calendar and change from year to year. As mentioned above, the lunar

year is just under 11 days shorter than the solar year, so although Islamic holy days are fixed in the Islamic calendar, they usually shift 10 or 11

days earlier in each successive solar year.

The fixed public holidays in Karakalpakstan are as follows:

| New Year's Day | 1 January |

| International Women's Day | 8 March |

| Nawrız Bayram | 21 March |

| Labour Day | 1 May |

| Victory or Memorial Day | 9 May |

| Independence Day | 1 September |

| Teachers' Day | 1 October |

| Flag Day | 18 November |

| Constitution Day | 8 December |

The most important Islamic festivals celebrated in Karakalpakstan today are Ramazan Bayram and Qurban Bayram. Note that the word

bayram means "festival" in Turkic but is translated as "holiday" in the Karakalpak dictionary. These festivals are also still sometimes

refered to as Ramazan Khayit and Qurban Khayit. Ramazan Bayram falls on the 1st day of Shawwal, the first day

following the ninth and fasting month of Ramazan. Qurban Bayram falls on the 10th day of Z'ul-Hijja, the last Islamic month,

celebrating the last day of the greater Hajj. Less attention is paid to the Prophet’s birthday, Mawlid-un-Nabi, celebrated by

Sunnis on the 12th of Rabi'-al-Awwal, the third Islamic month, and by Shi'as five days later.

The following table gives the approximate dates of the start of these festivals in the Gregorian calendar over the next few years. Note that these

are approximate since the start of months like Ramazan depend on the first sighting of the new moon with the naked eye and this can vary according

to geographical location.

Dates of recent and forthcoming Karakalpak religious festivals.

| Year | Islamic

New Year | Prophet's

Birthday | Qurban

Khayit | Ramazan

Khayit |

|---|

| 2002 | 15.03 | 24.05 | 23.02 | 06.12 |

| 2003 | 04.03 | 13.05 | 12.02 | 25.11 |

| 2004 | 21.02 | 02.05 | 02.02 | 14.11 |

| 2005 | 10.02 | 21.04 | 21.01 | 03.11 |

| 2006 | 31.01 | 11.04 | 10.01 | 24.10 |

| 2007 | 20.01 | 31.03 | 01.01 & 20.12 | 13.10 |

| 2008 | 10.01 | 20.03 | 08.12 | 02.10 |

| 2009 | 29.12 | 09.03 | 27.11 | 21.09 |

| 2010 | 18.12 | 26.02 | 16.11 | 10.09 |

| 2011 | 07.12 | 15.02 | 06.11 | 31.08 |

| 2012 | 29.11 | 04.02 | 26.10 | 20.08 |

Ramazan Bayram is a three-day festival and Qurban Bayram is a four-day festival. The first day of each is designated a public

holiday under the 1992 Constitution of Uzbekistan. In 2007 Ramazan Bayram is on 13 October and Qurban Bayram occurs twice, on

1 January and 20 December.

Modern holiday festivals can be classified into three main types: seasonal or agricultural; religious, and political. In addition there are numerous

cultural festivals covering art, music, dance, sport and folk culture, as well as special days reserved for particular crafts or professions such

as farmers' day and builders' day.

Seasonal Holidays

New Year's Day

New Year's Eve is mainly celebrated at home with friends and plenty of vodka to see in the New Year. Some families exchange presents with each other

and telephone friends and family. Some even have a New Year tree with lights and decorations. There is a firework display in No'kis.

The idea of a tree for New Year goes back to the time of Stalin. In the face of popular opposition Stalin lifted the ban on Christmas trees in 1935,

declaring them to be New Year's trees. New Year or Novyi God was declared to be a national family holiday – in effect a surrogate Christmas

stripped of any Christian meaning.

Incidentally 25 December is just a normal day in Karakalpakstan.

Nawrız

The vernal or spring equinox is the day when the number of daylight hours and the number of night time hours are equal and occurs around 21

March. Consequently the festival of Nawrız, or Nawrız Bayram, signifies the onset of spring and the commencement of the

agricultural growing season. However it is frequently cold and grey at this time of the year in Karakalpakstan. It is not until mid-April that

the trees begin to turn green, much later than in Bukhara, Samarkand or Tashkent.

During the Soviet era the Nawrız festival was suppressed. Following independence it has made a strong comeback.

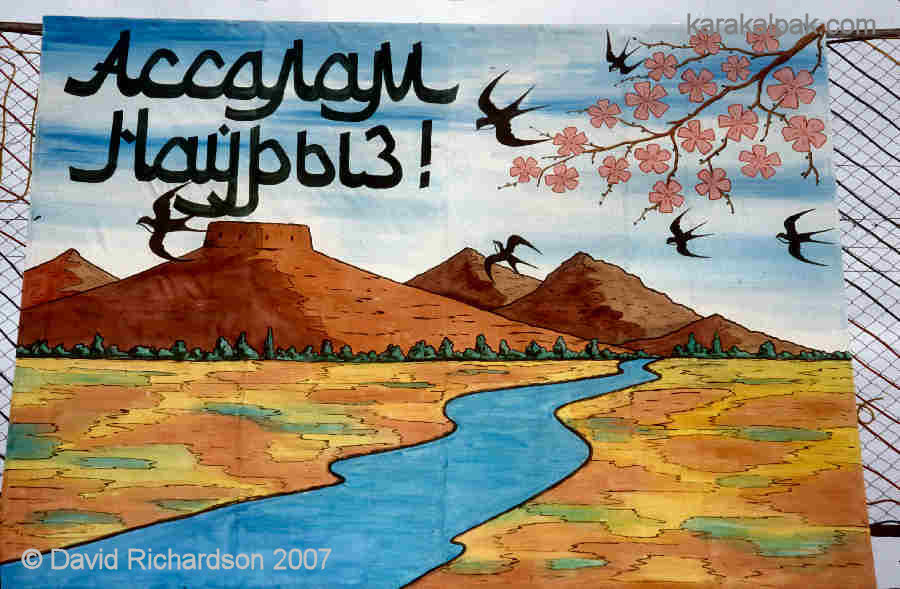

A painted sign in No'kis declaring "Assalam Nawrız", a peaceful Nawrız holiday.

The Zoroastrian "tower of silence" at Shılpıq is seen as an important symbol of the Karakalpak homeland.

In Karakalpakstan Nawrız is celebrated in No'kis with a public festival of dance and song, usually monopolised by officials, and a holiday

bazaar and funfair for families and children. In the city centre trucks are parked to block the main roads and there is a high police presence. The

dance festival, held in the open air theatre, is surrounded by hundreds of armed militia.

Firework display at the Nawrız celebrations in central No'kis.

Nearby, close to the Savitsky Museum, there is a small fun fair and many stalls selling shashliq, cakes, and souvenirs.

Food sellers in front of the big ferris wheel at the No'kis fair.

Stuffed horses for a children's ride.

A children's swing at the Nawrız fair in No'kis.

Shashliq stall at the Nawrız fair.

Slices of cream sponge cake sold from an old pram in No'kis.

Cooking up a mega festival plov.

At home families celebrate with traditional holiday food. This includes bawırsaq, festival plov and the ritual dish sumalyak,

adopted from the Khorezmian Uzbeks. Sumalyak is a slow-cooked dish that has a distinctive taste somewhat like a molasses-flavoured cream.

It is made by soaking the wheat grain for three days until it sprouts with tender green shoots. This is then ground, mixed with oil, sugar and flour,

and then cooked for 24 hours. The sprouting wheat grain symbolises new life, abundance, and health. The Karakalpak festive table, or

dasturqan, should be covered with an abundance of dishes and sweets and the diners should feel full and happy, thus ensuring that

the coming year will be safe and the crop will be plentiful.

Following Nawrız the work in the fields begins. In the past this was accompanied by the performance of various ceremonies. For example, before

going to the field the horns and neck of the bull were treated with oil. Then the first furrow was ploughed by the most respected and eldest member

of the community.

Paxta Bayram

The Paxta Bayram or cotton holiday is essentially a harvest festival to celebrate the successful completion of the important cotton harvest.

It was introduced following agricultural collectivisation in the 1930s and was organised on a sovxoz or kolxoz-wide basis,

usually in December. It incorporates some of the traditional Karakalpak games and sports.

As a community celebration it often involved traditional Karakalpak games and sports, such as qızquw, in which the participants have to tag

a running girl, wrestling, horse racing, ram fighting and cock fighting. The highlight was the violent and chaotic game of

ılaq oyın, the Karakalpak version of the Uzbek game kok-boru or blue wolf and the Afghan buzkashi.

A game of Karakalpak polo next to Shılpıq in the early 1980s, using the corpse of a headless goat.

The game is known as ılaq oyın in Karakalpakstan.

Two teams of riders fight among each other on horseback for the possession of a headless goat or sheep carcass. There are few rules. The carcass is

dropped in the centre spot between the two teams who then compete, with no holds barred, to pick it up and to score points by escaping from the rest

of the pack to round a marker and deposit the goat in the scoring circle.

The Karakalpak owner of this young camel had recently won it as the first prize in a ılaq oyın game.

Qazayaqlı awıl, May 2005.

Following the droughts and abysmal harvests of 2000 and 2001, the festival was temporarily abandoned.

Religious Festivals

Being overwhelmingly Muslim, the Karakalpaks still follow the cycle of rituals and feasts laid down by the Qu’ran, albeit in a rather loose

and relaxed fashion. Sixty-six years of Soviet rule has tempered the expression of local religious beliefs and even after fifteen years of

independence mosques are strictly regulated and are few and far between.

Ramazan Bayram

In Karakalpakstan life tends to go on much the same as usual during Ramazan. For politeness people avoid eating overtly in public, doing so with

more discretion.

Once the next first crescent of the new moon has been officially sighted by a reliable source the month of Ramazan is declared over and the month

of Shavval begins. The end of Ramazan is marked by a three-day period known in Arabic as Eid ul-Fitr, the Festival of Fast Breaking.

It is meant to celebrate the spiritual and moral cleansing achieved during Ramazan.

In Karakalpakstan today the festival is called Ramazan Bayram, Ramazan Khayit or sometimes Ruza Khayit. However the

Qazaqs still retain the old name of Oraza Ait. It traditionally begins with a special prayer and is a happy holiday

associated with socializing, visiting sick and elderly relatives, the preparation of a festive family meal, and sometimes by very modest gift-giving,

especially to children. The traditional charitable donation is known as a fitr and is intended to be sufficient to feed one poor person

for one day. It is intended to remind the donor about the suffering of others.

Qurban Bayram

About 70 days after the end of the month of Ramazan the Karakalpaks celebrate Eid ul-Adha, the Feast or Festival of Sacrifice, the

most important feast of the Muslim calendar. It is sometimes called the Greater Feast, while Ramazan Bayram is called the Lesser Feast.

This feast concludes the greater Hajj.

Today the Karakalpaks call this four-day long festival Qurban Bayram or Qurban Khayit. It too is meant to commence with a

prayer and religious sermon and involves less festivity than Ramazan Bayram. It is a time for dressing up, visiting friends or those

who are sick or lonely, visiting the graves of relatives, and receiving guests. In rural areas some people still slaughter an animal such as a

chicken or a goat and prepare a feast for the whole family. In the towns it is a chance to eat a special meal.

Incidentally very few Karakalpaks ever undertake the Hajj itself. According to an official Uzbekistan government press release, between

1991 and 2006 only 53,000 Muslims from the whole of Uzbekistan (with a population of 26 million) participated in the Hajj – two in every

thousand – not surprising given the cost. The proportion of Karakalpaks undertaking the Hajj is likely to be considerably lower.

Soviet-inspired Holidays

Prior to its collapse Karakalpakstan recognised all the official festivals and holidays celebrated throughout the Soviet Union. The most

important of these was the Day of the Revolution of the Proletariat, the anniversary of the Great October Revolution, celebrated on 7 November

(the Revolution took place on 25 October in the old calendar). This was introduced by Lenin himself in 1918. Another significant date was

1 May, the Day of International Worker Solidarity.

Official Soviet celebrations in Lenin Square, No'kis.

A poster of Karl Marx oversees a Soviet parade in Lenin Square, No'kis, in the early 1980s.

Equally relevant in Karakalpakstan was 20 March, the anniversary of the founding of the Karakalpak ASSR in 1932 and more importantly the

14 October, the anniversary of the formation of the Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast.

There were numerous other secondary commemorative days, ranging from Lenin Day, the anniversary of Lenin’s death on 23 January; Red Army

Day on 23 February, the Anniversary of the Founding of the Communist International (Comintern) on 4 March 1919; Pioneer Day on 19 May;

and later even a Stalin Day on 21 December, Stalin’s birthday.

Officials being welcomed with flowers at an official Soviet Bayram.

In front of the Lenin Monument in Lenin Square, No'kis, in the early 1980s.

The origins of International Women's Day on 8 March go back to the German socialist Clara Zetkin, who organized an International Conference

of Socialist Women in 1907 and fought for women’s suffrage. In 1909 the American Socialist Party declared the last Sunday in February to be

National Woman's Day. An International Women’s Day demonstration by women textile workers on 23 February 1913 in Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg)

turned into bread riots that escalated into the February Revolution. After the October Revolution the 8 March was set aside as the date for

celebrating Soviet International Women’s Day. It corresponded to 23 February in the old Russian calendar.

Following the defeat of Nazi Germany at the end of the Great Patriotic War, Victory Day - also called Commemoration, Memorial or Respect Day -

was established on 9 May, the day after the official ending of the war in Europe at midnight on 8 May 1945. Artillery Day on 19 November

celebrated the start of the counter offensive at Stalingrad.

During the 1960s and 1970s a whole string of commemoration days for particular groups of workers were introduced – ranging from cosmonauts,

fishermen, builders, and miners to geologists and physicians. Teachers' Day was introduced in 1965.

Many of these lost their original meaning as the decades passed. For example Red Army Day turned into a celebration for men in general, a

Men's Day, complementing Women's Day, which took place two weeks later. In turn Women's Day ceased to be a celebration concerning the

international solidarity of women and their emancipation under Communism and turned into something akin to the Western Mothers' Day. The

Day of International Worker Solidarity, 1 May, turned into a festival of spring somewhat similar to Nawrız!

Most of these holidays and anniversaries were swept away following the Soviet collapse. Only three of the least political anniversaries remain

today – Victory Day, International Women's Day, and Teachers' Day.

Victory Day remains a solemn day of remembrance for the 20 million Soviet military and civilian casualties of the Second World War. Though not

as severely affected as western Russia, many Karakalpaks, Qazaqs and Uzbeks from Karakalpakstan lost their lives in the conflict with Germany.

|

Soviet war memorial in To'rtku'l.

The war memorial in the former fishing hamlet of U'shsay.

Concrete memorial to the Great Patriotic War at Moynaq, which once overlooked the shoreline of the Aral Sea.

Women's Day is little different from Mothers' Day in the West - an opportunity for giving flowers to mothers, sisters and wives - apart from also

being a public holiday.

On the eve of the Teachers' Day holiday students bring small gifts as a token of thanks to their teachers. Some schools organize a party for

their staff.

Official Uzbek Holidays

Uzbekistan Independence Day

The most important official public holiday of all is currently Independence Day, celebrated on 1 September. The Uzbek SSR declared its

independence from the USSR on 31 August 1991. In 2006 the country celebrated its 15th anniversary as an independent republic.

Independence Day, also known locally as Istiqlal Bayram, is marked by huge national celebrations. The day is associated with blanket

TV coverage of traditional dancing and the performance of nationalist songs, interspersed with the President's speech. It is also marked by

intensive high security - the government clearly see the day as a major potential opportunity for opposition or terrorist activity. As the

holiday approaches there is a visible increase in police presence and road check-points go on heightened alert. A major display of dance and

song is held in No'kis for government and other important officials, who are protected by road blocks and a huge police presence.

Constitution Day

Constitution Day is celebrated in honour of the adoption of the new constitution of independent Uzbekistan on 8 December 1992.

During the Soviet era Constitution Day was celebrated on 5 December. However in 1977 it was shifted to 7 October, commemorating the

replacement of the Stalin Constitution by the Brezhnev Constitution.

On 2 March 1992 Uzbekistan was received in the United Nations Organization and this is now a political holiday in Uzbekistan.

Enforced Cultural Change

For the last three centuries holidays and festivals have been imposed on the Karakalpaks by the ruling colonial power as a means of reinforcing

its own social values and political ideology.

In the early 18th century the Karakalpaks living in the environs of the Syr Darya were subservient to the Qazaqs of the Lesser and the Middle

Horde. Their Islamic beliefs were strongly influenced by the Yasawiyya Sufi order of xojas, descendants and disciples of the early

Sufi saint Khoja Ahmed al-Yassawi, a modest man who was born and studied in Sayram, close to modern Chimkent, and moved to Yasa (today the

city of Turkestan) after the death of his father. He died there in 1166 AD and his mausoleum was constructed some 200 or more years later

under the orders of Timur. The spread of his ideas among the Qazaq nomads is generally attributed to his inclusion of traditional Turkic

cultural and shamanic beliefs into the Islam faith. He even wore Turkic costume, permitted the use of the Turkic language for religious

discussions other than prayer, used the sacrifice of cattle in certain rituals, and permitted women to participate in religious rituals.

As already mentioned, religious leaders were highly respected among the Karakalpaks in the 18th century. The most senior leaders were the

xojas, the direct descendants of Ahmed Yassawi, below which came the shayıqs, a term derived from the Arab and Persian

word for elder. In a system somewhat analogous to that applied to the craft industries the religious clergy were restricted to specific

family communities directly descended from Yasavi, who bore the family name xoja.

As the Karakalpaks moved from the valley of the Syr Darya to the lower reaches of the Amu Darya so they swapped the yoke of the Qazaqs for

that of the Khivan Uzbeks. The influence of the Qazaq xojas was replaced by that of the Khivan ishans, a different Sufi

sect who used both the Islamic lunar calendar and the local Khorezmian zodiacal calendar.

The Russian conquest of Khiva in 1873, led by General Kaufmann, and the subsequent annexation of the right bank territories had little impact

on Karakalpak cultural and religious life. Since Ivan the Terrible's conquest of Kazan in 1552 Russia had systematically repressed its

Islamic colonial subjects, destroying their mosques and medressehs and forcibly converting them to Christianity. However when Catherine the

Great came to power in 1762 she supported her more enlightened administrators and introduced a far more tolerant attitude to Islam. Muslims

ceased to be persecuted, forcible conversion came to an end, and the construction of new mosques was even encouraged. Official "spiritual

assemblies" were established to oversee the Islamic clergy, one being located in Orenburg.

As the first Governor-General of Turkestan, Kaufmann maintained this liberal attitude to Islam. Kaufmann had already experienced 13 years of

military service during the long and bloody conquest of the Caucasus, the brutality and insensitivity of the Imperial army exacerbating local

resistance to Russian rule. Consequently Kaufmann made no attempt to interfere with the religious beliefs and practices of his colonial

subjects. The Karakalpaks (and the Khivan Uzbeks) were left to follow their traditional practices and celebrations.

However we should not automatically assume that all Karakalpaks (or Uzbeks) were fully committed Islamists. When Henry Lansdell asked whether

Mohammedanism was progressing or going backwards in the Russian fort of Petro-Aleksandrovsk in 1882 he was told that the mullahs had little

influence and that the people were rather indifferent to religion.

Following the imposition of Soviet control after the creation of the Khorezmian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1923 and the Karakalpak Autonomous

Oblast in 1925, Karakalpaks came under gradually increasing pressure to abandon their traditional and religious beliefs. Lenin had

repeatedly emphasized that as far as the state was concerned religion was purely a private matter. But once in power the priority for the

Soviets was to indoctrinate the population with revolutionary Marxist ideology as a basis for irreversibly installing a socialist system of

government. To do this they needed to extinguish all traditional bastions of power, such as the feudal bays, their educated offspring,

and the Islamic religious establishment, along with the established system of beliefs.

Initially little changed other than that people became more discreet in the way that they pursued their faith. In 1927 the Soviet government

introduced the hujum, or offensive, against all social practices considered to be oppressive to women, such as the marriage of under-age

girls, the bride price, the tradition of seclusion and the veil. Again this had little real impact on the Karakalpaks. The main force of change

was economic not political – as women became increasing integrated into the workforce, so the old traditions became increasingly eroded,

especially in the urban areas.

It was Stalin’s purge of all nationalist and religious opposition between 1927 and 1938 that had the greatest impact. Legislation was introduced

in April 1929 to control religious associations, which henceforth had to be licensed by the newly formed Council of Religious Affairs, CRA, and

its regional commissioners. By the end of that year the majority of mosques had been forced to close. The teaching of religion had already

been forbidden in State schools long before compulsory primary education was introduced in 1930. Anti-religious pressure was applied through

a drive known as the Movement of the Godless. Central Asian Muslims were showered with a wave of propaganda and the Qur'an, the

Hajj to Mecca, and the Ramazan fast were all officially banned, the latter being considered harmful to economic progress. Unofficial

policy became more extreme, eventually seeking to liquidate religious communities and even individual believers. Stalin increasingly focused

on destroying the religious establishment utilizing intimidation, exile, imprisonment and even assassination. Takeyh and Gvosdev identify a

report that estimated over 10,000 members of the clergy were arrested and/or executed in Uzbekistan during the 1930s. By 1942 the number of

religious leaders across the USSR had been reduced six-fold as a result of murder or imprisonment.

Many Karakalpak mullahs and iyshans were among those persecuted during the purges between 1932 and 1938; religious land was confiscated

and mosques, medressehs and maktabs were closed. The height of the persecution occurred in 1937 under the Great Purge administered by

the infamous Nikolai Yezhov, head of the NKVD.

While many held on to their faith, some were influenced by the Marxist propaganda – by 1937 some 15% of adult Soviet Moslems described themselves

as non-believers. However these were mainly urban-educated technocrats who had been influenced by the ideas of Russian Marxists, not rural

peasants in northern Karakalpakstan.

From Moscow's point of view events in Karakalpakia were almost out of sight and the region avoided the excesses imposed elsewhere. Even when

official religious leaders were removed, unofficial mullahs stepped in to take their place. Despite the reign of terror many Karakalpaks,

especially the elderly, retained their religious beliefs but simply expressed them in private. In the meantime they were inundated with an

increasing number of official Soviet public holidays and commemorative days. Photographic evidence suggests that there was considerable public

support for events like the anniversary of the Great October Revolution during the 1930s. However we know that Bolshevik officials used threats

and coercion to rally public support. These were dangerous times and it was unwise to show any sign of public opposition to the regime.

Part of a ten-mile long procession in To'rtku'l in 1933 celebrating the sixteenth anniversary of the 1917 October Revolution.

Photographed by the Swiss explorer Ella Maillart.

The war with Germany eventually led to an unexpected relaxation in anti-Moslem policies as part of a bid to win the support of the Central Asian

masses. The consequent religious revival caused alarm in Moscow and led to a tightening of controls in 1947 and the closure of unofficial prayer

houses.

When Tatyana Zhdanko published her report in 1949 on life in the Karakalpak kolxoz named after the first Uzbek president Yuldash

Axunbabayev and located south of Shımbay she found that its members were celebrating two holidays a year – the Day of International

Worker Solidarity on 1 May and the Day of the Revolution of the Proletariat on 7 November. These revolutionary holidays had apparently

almost completely ousted the religious holidays of Nawrız, Ramazan and Qurban. The traditions of popular jollification

and public feasts had now been transferred from the religious to the revolutionary holidays.

Obviously Nawrız is not an Islamic holiday but was treated as such by the Soviets.

Zhdanko even witnessed one of the revolutionary holidays but did not specify which one. The day began with an official meeting of the

kolxoz members, after which prizes were awarded to shock-workers and those who had over-achieved (the so-called Stakhanovites).

After the meeting the workers dispersed to various celebratory feasts organized by each of the worker brigades or by individual families.

Sheep were donated from different homes and money was pooled to buy wine. The young people organised communal entertainments while the older

kolxoz members sipped tea in their yurts and listened to music and folk tales.

Zhdanko's report was written during the Stalin era and supported the communist party anti-religious line. What she was unable to say was that

the situation she observed followed several decades of terror and duress, after which only a fool would flout his or her religious convictions

in public. Although unintended, her report actually provides an insight into the widespread support still remaining for the old Islamic ways.

Two mullahs still lived in the awıl, falling under the jurisdiction of Kalibet iyshan, the head of the mosque in Shımbay.

They were supported by donations of money and food from the 1,574 kolxoz members. During Ramazan "the mullahs manage to

collect a fairly considerable sum ... from every member of the family, irrespective of his age or whether he is at home or absent." Each

individual donation was voluntary and consisted of one eighth of a batman of cereals. According to Henry Lansdell and Captain Spalding,

one Khorezmian batman was equivalent to 40 Russian pounds of 13 ounces, or 43 pounds avoirdupois. If only one quarter of the

kolxoz donated the required amount, this would equate to almost one tonne of cereals!

After the death of Stalin in March 1953 until the middle of 1957 anti-religious propaganda efforts were relaxed across Central Asia but did not

go away. As before Karakalpaks remained on the periphery of such activity. Quelquejay quotes statistics showing that from the 1 January 1955

to 1 August 1957 almost half a million copies of 22 anti-religious texts were circulated in Uzbekistan. However only 5,000 copies of two

of those 22 texts were circulated in Karakalpakstan. Karakalpaks were much less affected by such anti-religious propaganda than neighbouring Uzbeks.

Nikita Khrushchev's exposure of the cult of personality led to some positive changes and some national traditions became officially condoned.

Under a new approach folk traditions were classified as either progressive or reactionary. Thus labour traditions became acceptable but

religious traditions did not. Unfortunately because many traditional festivals and rituals had a religious element they remained officially banned.

At that time the main slogan was: "For a new life - new rituals", and the focus was placed on labour holidays and family rites.

Alarmed by the revival in religious activity Khrushchev launched another anti-religious campaign, which reached its height around 1961. In

Central Asia the new anti-Muslim campaign began in June 1957, having been preceded in March by a series of doctrinaire articles. It led to

increased scrutiny of traditional customs such as polygamy, the marriage of minor girls, the observance of religious holidays and the

Ramazan fast, as well as pilgrimages to local holy places. Mosques were closed and the clergy reduced in size.

The period from 1965 to 1985 saw a return to normality. The regime reluctantly came to see religion as a necessary evil that would have to

be endured although it was certainly not to be encouraged. Some former Karakalpak mosques were even reopened during Ramazan in the

1970s so that the faithful could conduct communal prayers.

|

In the early 1980s when Nawrız was still banned, springtime celebrations were held at the foot of Shılpıq.

The dance costumes bear no resemblance whatsoever to traditional Karakalpak or Uzbek dress.

A Karakalpak wrestling match during a festival at the foot of Shılpıq.

Karakalpak dancers with the Shılpıq "tower of silence" in the background.

A survey conducted by the Uzbek scholar Talib Saidbayev in the early 1970s, reported by Filimonov, showed that most Muslims in Karakalpakstan

did not follow strict Islamic guidelines. Amongst 2,500 believers in the Karakalpak ASSR 60% did not pray daily, 25% prayed as proscribed and

12% did so once or twice a day. Takeyh and Gvosdev report another aspect of this study in Karakalpakstan:

"... some 21% of the population was actively atheist, with approximately 25% active believers (either on account of faith or because of Islam

being traditional). Most of the population, however, fell into a grey zone, people who might observe some rites and traditions of Islam and

express religious sentiments, but who were neither committed atheists nor committed Muslim believers. Other, non-Soviet estimates indicated

that about 20 to 40 percent of the population of Central Asia engaged in daily prayer and that up to half made some effort to observe the Ramadan fast."

The selection of Mikhail Gorbachëv as the General Secretary of the Politburo in 1985 was followed by yet another crack-down on religious belief.

On a stopover in Tashkent following a trip to India, Gorbachëv criticised Uzbek Communist Party leaders who paid lip service to communist

principles whilst taking part in religious rituals. Subsequently over 50 Uzbek members were expelled from the party during 1987 for organizing

and taking part in "religious rituals". In Uzbekistan, traditional national religious rites were once again forbidden and Navruz was transformed

into a new non-religious spring festival called Novbachor. This gimmick gained virtually no acceptance among the populace and was

short-lived.

With growing economic and social crisis gripping the entire Soviet Union, Gorbachev was unable to wage a wider anti-religious campaign.

Gorbachev's message of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) increasingly encouraged people to express

their views in public and in the media. The grim reality of daily life was fully revealed and criticisms of the regime were aired openly.

People were exposed to previously banned publications and to Western news and entertainment. The genie was out of the bottle. In Central

Asia people began to feel more confident about expressing their Muslim beliefs and men with beards and women with headscarves were seen on

the street. The Soviet Republics too began to take an increasingly independent line from Moscow, emphasising their national traditions and

culture. On 2 Feb 1989 the Uzbek First Secretary Nishanov addressed a group of intellectuals and assured them that a package of measures

had been prepared for the upcoming CPSU Central Committee plenum on nationality issues concerning Uzbek cultural independence, including

measures to expand Uzbek language teaching and usage and the restoration of Navruz and other Islamic holidays. Later that year the

Uzbek government decreed the Uzbek language to be the official state language and re-established Navruz as a national annual folk festival.

In 1990 the USSR introduced a new law – the "Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations", which permitted both the freedom of worship

and the performance of religious rites. It barred the State from interfering in religious affairs.

After the declaration of independence and the formation of the Republic of Uzbekistan attempts were made to restore the pre-Soviet culture of

traditional rituals and festivals. Between 1991 and 1993 the President of Uzbekistan decreed the official celebration of festivals such as

Nawrız, Ramazan Khayit, and Qurban Khayit. Nawrız became a national one-day holiday as did the first day of both

Ramazan Khayit, and Qurban Khayit.

Following its separation from the Soviet Union in 1991 the Parliament of Uzbekistan founded a brand new political festival - Independence Day

of the Republic of Uzbekistan - to be celebrated on 1 September. Constitution Day was established on the 8 December, the date that the

Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan was accepted in 1992.

Interestingly in Russia it was not until 2005 that President Vladimir Putin abandoned the 7 November holiday celebrating the October

Revolution in favour of a slightly earlier Day of National Unity on 4 November. This controversial change has angered committed

Russian Communists.

Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms

To listen to a Karakalpak pronounce any of the following words just click on the one you wish to hear. Please note that the dotless letter

'i' (ı) is pronounced 'uh'.

References

Anon, Amu Darya Division, Turkestan Gazette, Number 10, 1875.

Brower, D., Islam and Ethnicity: Russian Colonial Policy in Turkestan, Russia’s Orient, Chapter 6, pages 115 to 137, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1997.

Critchlow, J., Islam and Nationalism in Soviet Central Asia, Chapter 8 in Religion and Nationalism in Soviet and East European Politics, edited by Pedro Ramet, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 1989.

DeWeese, D., The Politics of Sacred Lineages in 19th century Central Asia: Descent Groups Linked to Khwaja Ahmed Yasavi in Shrine Documents and Genealogical Charters, International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 31, pages 507 to 530, 1999.

Esbergenov, X., Chapter 1, Settlements and Dwellings [in Russian], in Ethnography of the Karakalpak from the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century, Fan Publishing, Uzbek SSR, Tashkent, 1980.

Filimonov, E. G., editor, Islam in the SSSR, The particuar process of secularisation in the Republics of the Soviet East, Publisher Mysl, Moscow, 1983.

Georgi, J. G., A Description of All the Nationalities that Inhabit the Russian State [in Russian], Volume 2, Saint Petersburg, 1776 to 1777.

Gladyshev, D. V., and Muravin, I., Journey from Orsk to Khiva and back, completed in 1740-1741 by Lieutenant Gladyshev and Geodesist Muravin [in Russian], Published by Khanykov, Saint Petersburg, 1851.

Hunter, S. T., Islam in Russia: the Politics of Identity and Security, M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, New York, 2004.

Ivanov, P. P., Description of the History of the Karakalpaks, Transactions of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Volume VII, edited by A. N. Samoylovitch, pages 9 to 90, Published under the Auspices of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, April 1935.

Jumashev, X. J., Chief Editor, Karakalpakstan, Photo Album, Publisher "Karakalpakstan", No'kis, 1984.

Karabaev, M., Festival-Ritual Culture as a Factor of Social Progress, Chapter VII in Spiritual Values and Social Progress, Uzbekistan Philosophical Studies I, edited by S. Shermukhamedov and V. Levinskaya, Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, Washington DC, 2000.

Karazin, N. N., In the lower reaches of the river Amu, Travel Descriptions [in Russian], Herald of Europe, Book 3, 1875.

Kaulbars, A. V., Lower reaches of the Amu Darya river, described from his own studies in 1873 [in Russian], Transactions of the Russian Geographical Society, Volume 9, Saint Petersburg, 1881.

Lansdell, H., Russian Central Asia, Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, Boston, 1885.

Morozova, A. S., The Domestic Cultural Life of the Karakalpaks [in Russian], Doctoral Thesis, Department of History, Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR, Tashkent, 1954.

Naumkin, V., editor, Khiva, Caught in Time: Great Photographic Archives, Garnet Publishing, Reading, 1993.

Nurmukhamedov, M K, Muminov, I M, and Dosumov, Y M, History of the Karakalpak ASSR, Volume 1, Fan Publishing House, Tashkent, 1986.

Privratsky, B. G., Muslim Turkestan, Kazak Religion and Collective Memory, Curzon-Routledge, London, 2001.

Quelquejay, C., Anti-Islamic Propaganda in Kazakhstan since 1953, The Middle East Journal, Summer 1959.

Remington, T. F., Renegotiating Soviet Federalism: Glasnost’ and regional Autonomy, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, Volume 19, Summer 1989.

Riza Quli Mirza, Brief Description of the Amu Darya Region. Saint Petersburg, 1875.

Ro'i, Y., Islam in the Soviet Union, From the Second World War to Gorbachëv, Hurst & Company, London, 2000.

Rychkov, P. I., The Topography of the Orenburg Region [in Russian], originally published in 1762 and reprinted by Kitap, Ufa, 1999.

Sobolyev, L. N., Letters about the Amu-Darya expedition, Russian Invalid, Numbers 213 and 216, 1874.

Takeyh, R., and Gvosdev, N. K., The Receding Shadow of the Prophet, The Rise and Fall of Radical Political Islam, Praeger, Westport, Connecticut, 2004.

Zhdanko, T. A., Everyday Life in a Karakalpak Aul, Soviet Ethnography, Number 2, 1949.

Zhdanko, T. A., and Esbergenov, X, Ethnography of the Karakalpak from the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century [in Russian], Fan Publishing, Uzbek SSR, Tashkent, 1980.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|

|

![]()

![]()