Karakalpak Yurt Construction

|

Karakalpak Yurt Construction

|

|

ContentsTraditional Yurt Workshops in KhorezmThe Shımbay Yurtmaker Door Carpentry Roof Felts Shiy Screen Makers Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms References Traditional Yurt Workshops in KhorezmYurts were traditionally made in small workshops by specialist yurtmakers, known as u'yshi. In the past there were a multitude of yurt workshops throughout the Aral Delta, often located close to a river and a local source of timber. For example there are records from the late 19th century mentioning a yurt workshop to the south-west of Shımbay located on the west bank of the Kegeyli River. Aleksandr Melkov visited a yurt maker in Shımbay region in 1929 and collected some of the specialist yurtmaking tools. He also acquired a yurt frame which was subsequently shipped to the Museum of the Ethnography of the Peoples of the USSR in Leningrad (inventory number 5111-1-139). Around 1950 Zadykhina encountered a yurt that had been made by an Uzbek master at Qıpshaq in southern Karakalpakstan in the early 1930s. In the past there were many other yurtmakers working in this region.In the very same year of 1929 the Sixteenth Conference of the Soviet Communist Party adopted the first Five-Year Plan. It was dubbed the "Second Revolution", designed to eliminate private property and transform traditional ways of living and working. Its main impact in the Karakalpak Oblast was on private landowners and farmers, whose land and livestock was confiscated and collectivized. However it also affected all of the small private yurt workshops, which were also nationalized and became swept up within new regional industrial combines or artels. Other components for the yurt, such as shiy screens and tent bands, were not manufactured in workshops but in the home. It was traditional for a future bride to make all of the yurt weavings as part of her dowry. Even so, some craftwomen did specialize in certain crafts and took on orders for friends and neighbours or sold their produce at the bazaar.

Karakalpak shiy making in the 1930s, in the garden next to the yurt.

Even in the 1960s there was still a strong local demand for yurts within the Karakalpak ASSR and the main workshops could be found

in the Qon'ırat, Xojeli, Shımbay, and Kegeyli regions. They did not specialize in particular ethnic designs, but produced

Karakalpak, Qazaq, and Turkmen yurts according to demand. Even an Uzbek yurt could be made as a special order, although the requirement

for this style was by then almost non-existent.

Karakalpak yurt maker's workshop at U'yshi awıl in 1976.

|

|

His workshop is located in a Shımbay backstreet. Double gates open into a large yard stacked with various

types of local timber. Flat-roofed single storey adobe buildings surround the yard. As you enter the separate

workshops and store rooms, each lit by a single small window, it takes a while for your eyes to adjust from

the bright sunlight outside. The floors are just bare earth and there are no machines. The few pieces of

equipment that are in evidence look simple and primitive. Yet it is clear from the inventory of finished parts

that the workshop is very effective at turning out yurts.

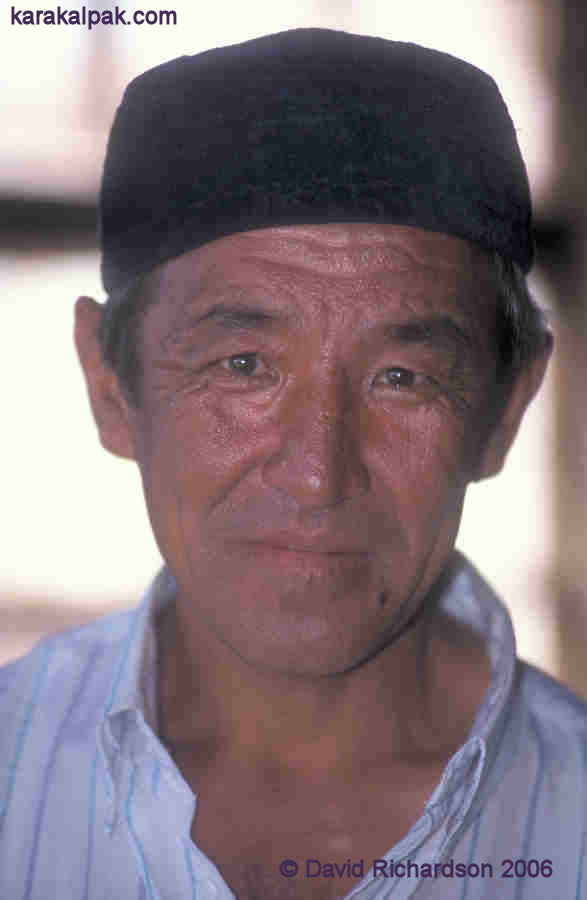

Quwanıshbay decided to become a yurtmaker after secondary school and trained for one year. This seems to have

been short as the usual period of apprenticeship used to be three to four years. The yurtmaking profession is

open to anyone and is not restricted to any specific clan. Quwanıshbay began to make his own yurts in 1970.

Eleven men are employed in this workshop and business is often slow. However on one of our visits they were

busy completing a large order for five yurts to be used at a bar in Tashkent!

|

Quwanıshbay is ethnically a Qazaq, but he makes both Qazaq and Karakalpak style yurts depending on the

preference of the customer. He has been able to show us the fundamental differences between these two types.

| Yurt Feature | Qazaq | Karakalpak |

| Uwıq | Bent so that the roof seems hemispherical. Decorated with a row of grooves at the top. | Straighter so that the roof appears cone-like. Undecorated. |

| Kerege | Inner laths run from bottom left to top right, the same as the Uzbek and the Kyrgyz yurt. |

Inner laths run from top left to bottom right the same as the Turkmen yurt. |

| Shan'araq | Single wooden ring, usually decorated with carving. Central laths are parallel. No decorative ‘arrows’. |

Two concentric wooden rings, generally plain. Central laths fan out. Four sets of three decorative arrow shapes. |

|

Yurts now come in mainly three sizes: 6, 8, and 12-sections or qanats. In the past 4 or 5-section

yurts were more common but now the main requirement tends to be for larger 8-section yurts, often because

families are bigger. In 2002 the price of a 6-section yurt was about 70-80,000 som to purchase

locally (about $200) and it took between 4 to 6 weeks to make.

Modern yurts are not the same as traditional yurts. The old varieties of wood are no longer available, it is

hard to maintain traditional skills when demand is so low, and there are no longer the wealthy landowners to

patronize the finest masters. For example old people in the Kegeyli and Shımbay regions told researchers from

the Khorezm Archaeological and Ethnographic Expedition that in the olden days the upper part of the kerege

of yurts belonging to wealthy bays was decorated with carved bone and silver.

At the same time the sizes are slightly different. In traditional Karakalpak yurts the qanats were

about 1.3 to 1.4 metres high and 2.1 to 2.4 metres long. The average qanat had seventeen keregebas.

Today the qanats are a little longer. Quwanıshbay's craftsmen told us that today:

| - a 6-qanat yurt has a diameter of 5.4 metres and needs 110 uwıqs that are 2.9 metres

long and a shan'araq with a diameter of 1.9 to 2.0 metres. |

| - an 8-qanat yurt has a diameter of 6.5 metres, needs 130 uwıqs that are 3.3 metres

long and a shan'araq with a diameter of 2.2 metres. |

|

Quwanıshbay's yard is always full of aq tal and qara tal wood from local suppliers, seasoning in

the open air. He told us that in the past he used janewut (Salix songarica Andersson) which he compared in strength to iron or steel.

A yurt made from janewut lasts for 100 years; but one made from qara tal lasts only 20 years.

Janewut was also used for ceiling beams in houses. Janewut was an endemic species, which grew wild

in the tugay forest, reaching a maximum height of only 3 metres. At one time it was even cultivated. It

was quite different from aq tal and qara tal, being more slow-growing, and the wood was not so straight.

It took 5 years for janewut branches to reach the same size that qara tal reached in 3 to 3½ years.

Quwanıshbay had no idea why there are no janewut trees left, although local botanists have told us that

increasing soil salinization has eliminated most of the endemic plant species from the delta. A recent survey showed how rare it has become,

now making up less than 1% of the forest cover and growing only in the part of the forest near the Amu Darya river in the Bada Tugai.

Special forest conservationists started to plant janewut in the Badai-Tugai forest reserve in 2000-2001.

Quwanıshbay now uses aq tal for the shan'araq as it bends more easily and qara tal for the

kerege and uwıqs as it is stronger. The wood is allowed to dry for one month. If it were left

longer it would become too dry.

When they are ready to begin work they soak the poles that will be used as uwıqs (the struts which connect the

lattice walls to the roof wheel) in water covered with wood shavings to prevent evaporation. In the next process they

are heated in a tall thin oven called a morı for 3 to 4 hours. The morı is heated by hot gases fed

though an underground pipe from a charcoal fire burning in a nearby earthen pit. The wood becomes softer due to the

smoke and heat and can therefore be bent more easily.

|

The poles are bent by means of a tez, located next to the morı. The tez is basically a stout

wooden log positioned on the edge of a deep pit and fixed to the ground by means of large wooden and metal pins. Two

strong pegs protrude from holes drilled in the top of the log – these are usually wooden pegs but in some cases a metal

spindle from an old piece of machinery is used instead. The pole to be bent is taken from the oven and placed between

the pegs, one end pointing down into the pit. It is then forcibly and progressively bent to form a short arch using a

heavier wooden pole for leverage. This is hot and backbreaking work. As the poles are bent they must be constantly

checked against a pro-forma pattern piece. You can hear the wood cracking as it is bent and afterwards the bent pole

looks almost broken.

|

Now the bent poles must be hand-planed. Instead of a mechanical vice the workshop has a number of stout wooden logs

sunk into the ground, their tops protruding vertically from the floor by about one metre. A u-shaped notch has been

cut into the top of each log. The yurtmaker takes each bent pole and places it in the notch. He then uses a second

heavier pole to wedge the first pole in place, using his thigh to create leverage. This leaves both hands free to plane

the uwıq using a sharp spoke-shave.

|

|

The shorter poles (known as sag'anaq) that make up the qanats also have to be bent, but only by a small

amount. This is so that the qanat forms an arc when it is opened. After planing and drilling, the slightly

bent sag'anaq are joined using strips of wet camel hide. These fastenings are called qam ko'k or

qam qayıs, the word qam pertaining to raw and qayıs meaning strap. The camel hide, which

is stronger than cowhide, is bought on the market. Some of the finished parts (uwıqs, qanats etc.)

are retained as patterns for the future.

At present the workshop usually makes 6 to 8 eight-qanat yurts a year. Between 1989 and 1991 they made up to 14 a year.

The roof wheel is made of heavier gauge wood but is bent in exactly the same way. Three bent sections, known in English

as fellies, are used to make each wooden wheel. The exact shape is obtained by matching them against a circle drawn with a

large pair of wooden compasses known as a palger. The fellies are scarfed together and the joints are held in

place with stout metal wires. They were traditionally joined with a binding of rawhide, a process known as iskenje.

|

The wooden frame is sometimes covered in red clay (josa) as a preservative and colorant. This comes from Qırantaw

and is believed to also provide protection from woodworm. According to Quwanıshbay animal blood is sometimes used instead,

but we were unable to verify this with any other sources. We know that some museum and tourist yurts (such as those at the

Ayaz qala yurt camp) are painted with red gloss paint instead, which is definitely not traditional.

Door Carpentry

The workshop makes the yurt frame but not the door due to the longstanding belief that a yurtmaker would die if he made all

of the parts of the yurt. The doors of Karakalpak yurts were often plain and undecorated. Carving and, in particular,

painting of the doors in bright colours became more popular in the 1940s and 1950s. In the 1920s and 1930s this had

been considered to be "Qazaq taste".

|

We were introduced to the local Shımbay carpenter who made the doors for Quwanıshbay's

yurts. According to Savitsky some craftsmen preferred to use Amu Darya willow (Salix oxica, known locally as sog'ıt),

or pine (qarag'ay) for the door panels. According to our research sog'ıt was indeed used for door panels but its botanical name is Salix alba. Salix oxica is in fact aq tal.

It also seems strange that he refers to the use of pine, as both pine and birch (qayın') are generally considered by the Karakalpaks to bring misfortune and sterility.

|

The yurtmakers workshop also cuts out the shapes for the three roof felts. The felt is bought on the market in Hazarasp

or is imported from Turkmenistan. There is only one former sovxoz near To'rtku'l (Ilyich) which still makes felt

in Karakalpakstan. The yurtmakers mark out the shape of the felt on the ground in the workshop yard using white paint and

use this as a pattern for cutting the felt.

Shiy Screen Makers

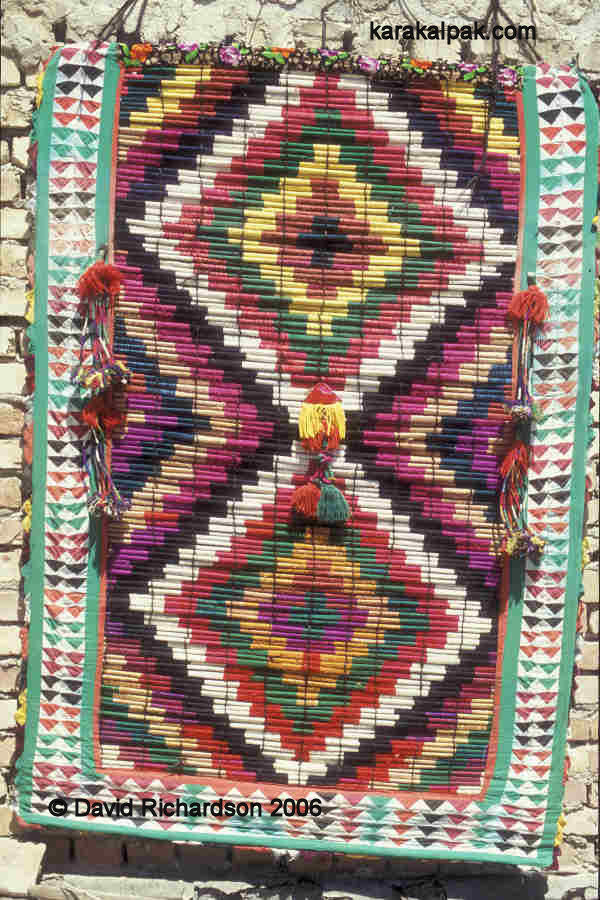

The shiy screens used to be made by yet another expert from a nearby village. They could be decorated and a

complete set could take from several months to a year to make. Unfortunately the shiy screen maker died in 2003

so the workshop now purchases them from the Shımbay Sunday market. They also know of someone still making screens near

Qazaqdarya.

|

In the past these screens were made from the stems of the tall and slender perennial steppe grass, shiy - Lasiagrostis

splendens (Trinius) Kunth, also known as Stipa splendens Trinius or Achnatherum splendens (Trinius) Nevshi,

sometimes called chee grass in English. Shiy occurs widely across Central Asia, from European Russia to Northern India,

Mongolia, and China, where it forms dense tussocks. It is valued for its strong, tall, and slender stems, which grow up to 2½ metres

tall and are ideal for matmaking. Herbert Wood commented on the alluvial islands in the Amu Darya close to Khiva in 1873, whose covering

of young willows was hidden in the summer by thick crops of high golden-eared waving grass (Lusiagrostis splendens [sic]). A

little later Henry Lansdell encountered it growing on the banks of the Amu Darya just upstream from To'rtku'l. Unfortunately this plant

is no longer common in the Aral Delta as it cannot cope with the increasingly high levels of salinity, despite being a salt-tolerant species.

Today the screens are made of reeds, yet still retain the name 'shiy screens' regardless of the material from which they

are made. They are usually constructed using goat’s wool, which was and still is readily available but needs great skill to spin.

Sometimes cotton is used instead but this is more susceptible to weather rot. In many Karakalpak villages all of the outhouses and

fences for livestock areas are made of reeds. In the past many poor people who could not afford felt for the yurt roof used reeds

instead. Indeed some of them inhabiting the northern delta even built yurt-like dwellings entirely out of reed.

|

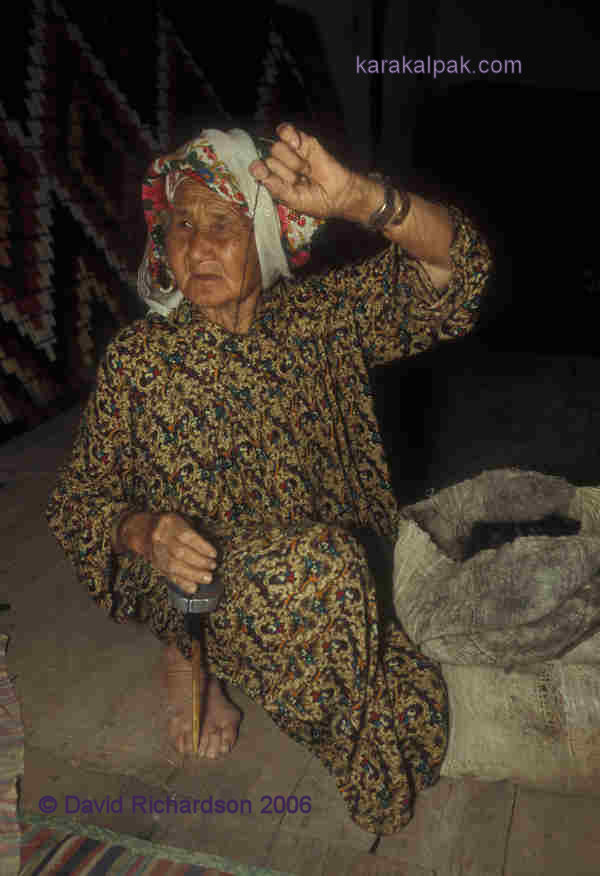

We have visited two women who made different types of shiy screens. Gu'lxan apa (from the Qon'ırat Jawıng'ır-Tiyekli clan)

was born in 1926 but did not learn to make shiy screens until she was in her forties. She makes jez shiy –

screens where the reeds are wrapped with wool to form a pattern in the same way as Kirghiz reed screens. She told us that

she believed the Qazaqs learnt this from the Karakalpaks. Esbergenov mentions the use of jez shiy screens on either

side of the yurt door instead of the shiy o'n'ir. However Gu'lxan apa told us that jez shiy were used internally,

as they would fade if used externally. Anna Morozova writing somewhat earlier than Esbergenov asserted that Karakalpaks did not

produce patterned screens from shiy, tied with coloured wool and silk thread. She believed that in the past rich

Karakalpak families bought such screens from Qazaqs. However Shalekenov, writing in 1966, stated that Qazaqs living in

the vicinity of Karakalpaks made reed doors with patterns from different coloured wool “on the Karakalpak model”. We have

only seen a limited number of jez shiy screens and have been unable to ascertain their provenance. To the best of

our knowledge there are none in museums that can be specifically verified as Karakalpak so this remains an area of doubt.

According to Gu'lxan apa in the past a special kind of jez qamıs was used which is now no longer available. Now she

uses ordinary reed which is known as qamıs. Jez qamıs was not hollow

like qamıs and was very fine – about half the diameter. It was stronger and its surface was polished like qamıs.

It used to grow on high land, whereas qamıs grows very close to water. It was much shorter (about 1.2 metres) and two

pieces had to be joined together to get the right height.

Her children collect the qamıs. The qamıs from watery fields is not very good and the best qamıs

grows away from the water. The qamıs is sorted by length and diameter. The leaves are removed and it is washed.

Pairs are selected for wrapping and are first tied together in the centre, at the ends, and in between. She always wraps from

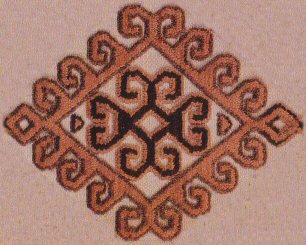

the centre and uses this as a reference point. She only makes one particular pattern which is typical for shiy.

Because the rhythm of this pattern consists of 3 elements she prepares them in one set, weaves them first, and then does the

next set. It takes one week to do one diamond and about one month per screen. When we visited her she was making a screen

for her daughters so that they would have something to remember her by when she was no longer with them.

|

She uses goat hair to bind the qamıs, which has previously been wrapped with coloured wool, together. This is stronger

than sheep’s wool and resists sunlight better. She spins the goat hair herself – the family breed sheep and goats. She

separates the two types of goat hair before spinning, therefore some of the threads have a barbershop pole effect. It seems she

mainly uses the dark hair but uses the lighter when that runs out. She usually spins two balls of goat hair in one day. After

she spins them she plies two balls together. She puts this thread in water (it doesn’t matter what temperature and nothing is

added) for a certain length of time which she said was secret. This made the thread even stronger. If this was not done the

thread could un-spin itself. She buys the coloured wool from Xojeli bazaar on a Sunday and in 2004 it cost 2,800 som

for one kilogramme.

|

The top piece of wood is called the shiy a'gash or shiy pole. Any suitable piece of wood can be used but it

has to be straight. Special grooves are cut to keep the ‘warps’ the correct distance apart. The weights (awırlıq) used

for tensioning the strings are made of mud, rice husks, and wool. It was her idea to add some wool as it makes them stronger. The strings are in pairs with about five metres per side. She only moves every other set of stones for

each set of qamıs, thereby imitating a twill pattern.

|

Minayım Da'wenova (from the Qon'ırat Mu'yten-Teli clan) used to work at the Regional Studies Museum. She made the shiy screens

for the yurt which now forms part of their exhibition. She was taught this craft by her mother. Minayım moved to No'kis in 1968,

but before then she lived with her parents on the Qazaqdarya river, close to the coast of the Aral Sea in Moynaq rayon.

There was, of course, a plentiful supply of reeds in that area. Instead of shiy she used qamıs of less than

one centimetre in diameter. Stones as big as a hand were used to create enough tension. The simplest screens just had straight

lines of goat hair holding them together but ones with zigzags and other geometric patterns were also available. Wealthy people

could order a jez shiy screen with the qamıs wrapped in coloured sheep's wool in a particular pattern.

Mosquitoes could not get in through a carefully woven shiy screen. However moths were a problem for shiy wrapped

with sheep’s wool. They were not a problem if the shiy had been wrapped with goat’s hair.

Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms

To listen to a Karakalpak pronounce any of the following words just click on the one you wish to hear. Please note that the dotless letter

'i' (ı) is pronounced 'uh'.

| aq tal | palger | qara tal | shiy o'n'ir |

| awırlıq | qamıs | qayın' | sog'ıt |

| janewut | qam ko'k | risa'le | tez |

| josa | qam qayıs | sag'anaq | uwıq |

| kerege ko'z | qanat | shan'araq | u'yshi |

| morı | qarag'ay | shiy |

|

This page was first published in May 2006. It was last updated on 6 March 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |